Mapping the New Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K

Writers Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Monica Ali Isabel Allende Martin Amis Kurt Andersen K. A. Applegate Jeffrey Archer Diana Athill Paul Auster Wasi Ahmed Victoria Aveyard Kevin Baker Mark Allen Baker Nicholson Baker Iain Banks Russell Banks Julian Barnes Andrea Barrett Max Barry Sebastian Barry Louis Bayard Peter Behrens Elizabeth Berg Wendell Berry Maeve Binchy Dustin Lance Black Holly Black Amy Bloom Chris Bohjalian Roberto Bolano S. J. Bolton William Boyd T. C. Boyle John Boyne Paula Brackston Adam Braver Libba Bray Alan Brennert Andre Brink Max Brooks Dan Brown Don Brown www.downloadexcelfiles.com Christopher Buckley John Burdett James Lee Burke Augusten Burroughs A. S. Byatt Bhalchandra Nemade Peter Cameron W. Bruce Cameron Jacqueline Carey Peter Carey Ron Carlson Stephen L. Carter Eleanor Catton Michael Chabon Diane Chamberlain Jung Chang Kate Christensen Dan Chaon Kelly Cherry Tracy Chevalier Noam Chomsky Tom Clancy Cassandra Clare Susanna Clarke Chris Cleave Ernest Cline Harlan Coben Paulo Coelho J. M. Coetzee Eoin Colfer Suzanne Collins Michael Connelly Pat Conroy Claire Cook Bernard Cornwell Douglas Coupland Michael Cox Jim Crace Michael Crichton Justin Cronin John Crowley Clive Cussler Fred D'Aguiar www.downloadexcelfiles.com Sandra Dallas Edwidge Danticat Kathryn Davis Richard Dawkins Jonathan Dee Frank Delaney Charles de Lint Tatiana de Rosnay Kiran Desai Pete Dexter Anita Diamant Junot Diaz Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni E. L. Doctorow Ivan Doig Stephen R. Donaldson Sara Donati Jennifer Donnelly Emma Donoghue Keith Donohue Roddy Doyle Margaret Drabble Dinesh D'Souza John Dufresne Sarah Dunant Helen Dunmore Mark Dunn James Dashner Elisabetta Dami Jennifer Egan Dave Eggers Tan Twan Eng Louise Erdrich Eugene Dubois Diana Evans Percival Everett J. -

FICTION ALE Reservation Blues / Sherman Alexie

To borrow the titles mentioned below, please contact Circulation desk: 022-26724024 or write to us at [email protected] Call. No Particulars FICTION ALE Reservation blues / Sherman Alexie. BAG This place / Amitabha Bagchi. BAR Ship fever : stories / Andrea Barrett. BAU Hope was here / Joan Bauer. BLU In the unlikely event / Judy Blume. BRO March / Geraldine Brooks. BUR To the bright and shining sun : a novel / by James Lee Burke. CAP Crossers / Philip Caputo. CAS Spartina / John Casey CRU Whale talk / Chris Crutcher. DEX Paris Trout / Pete Dexter. DIC Deliverance / by James Dickey. DOE All the light we cannot see : a novel / Anthony Doerr. DUB The Lighting Stones/Jack Du Burl EUG Marriage plot / Jeffrey Eugenides. FLY Flying lessons & other stories / edited by Ellen Oh. FOR One year after / William R. Forstchen. FRE Go with me / Castle Freeman, Jr. FRI Where you'll find me / Natasha Friend. GAI The Mare: a novel/Mary Gaitskill GAR Beautiful creatures / by Kami Garcia & Margie Stohl. GAR Fate City/Leonard Gardner GAS Omensetter's luck : a novel / by William H. Gass. GLA Three Junes / Julia Glass. GRA Blood magic / Tessa Gratton. GRI Associate / John Grisham. HAR Art of fielding : a novel / Chad Harbach. HEN Fourth of July Creek : a novel / Smith Henderson. IRV Prayer for Owen Meany : a novel / John Irving. KLA Blood and chocolate / Annette Curtis Klause. LYN Inexcusable / Chris Lynch. MAC River runs through it / Norman Maclean ; wood engravings by Barry Moser. MAT Shadow country : a new rendering of the Watson legend / Peter Matthiessen. MAX So long, see you tomorrow / William Maxwell. -

AMERIŠKA DRŽAVNA NAGRADA ZA KNJIŽEVNOST Nagrajene Knjige, Ki

AMERIŠKA DRŽAVNA NAGRADA ZA KNJIŽEVNOST Nagrajene knjige, ki jih imamo v naši knjižnični zbirki, so označene debelejše: Roman/kratke zgodbe 2018 Sigrid Nunez: The Friend 2017 Jesmyn Ward: Sing, Unburied, Sing 2016 Colson Whitehead THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD 2015 Adam Johnson FORTUNE SMILES: STORIES 2014 Phil Klay REDEPLOYMENT 2013 James McBrid THE GOOD LORD BIRD 2012 Louise Erdrich THE ROUND HOUSE 2011 Jesmyn Ward SALVAGE THE BONES 2010 Jaimy Gordon LORD OF MISRULE 2009 Colum McCann LET THE GREAT WORLD SPIN (Naj se širni svet vrti, 2010) 2008 Peter Matthiessen SHADOW COUNTRY 2007 Denis Johnson TREE OF SMOKE 2006 Richard Powers THE ECHO MAKER 2005 William T. Vollmann EUROPE CENTRAL 2004 Lily Tuck THE NEWS FROM PARAGUAY 2003 Shirley Hazzard THE GREAT FIRE 2002 Julia Glass THREE JUNES 2001 Jonathan Franzen THE CORRECTIONS (Popravki, 2005) 2000 Susan Sontag IN AMERICA 1999 Ha Jin WAITING (Čakanje, 2008) 1998 Alice McDermott CHARMING BILLY 1997 Charles Frazier COLD MOUNTAIN 1996 Andrea Barrett SHIP FEVER AND OTHER STORIES 1995 Philip Roth SABBATH'S THEATER 1994 William Gaddis A FROLIC OF HIS OWN 1993 E. Annie Proulx THE SHIPPING NEWS (Ladijske novice, 2009; prev. Katarina Mahnič) 1992 Cormac McCarthy ALL THE PRETTY HORSES 1991 Norman Rush MATING 1990 Charles Johnson MIDDLE PASSAGE 1989 John Casey SPARTINA 1988 Pete Dexter PARIS TROUT 1987 Larry Heinemann PACO'S STORY 1986 Edgar Lawrence Doctorow WORLD'S FAIR 1985 Don DeLillo WHITE NOISE (Beli šum, 2003) 1984 Ellen Gilchrist VICTORY OVER JAPAN: A BOOK OF STORIES 1983 Alice Walker THE COLOR PURPLE -

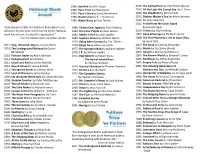

Fiction Winners

1984: Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson National Book Award 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2004: The Known World 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike by Edward P. Jones 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay 1979: Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride 1978: Blood Tie by Mary Lee Settle 2001: The Amazing Adventures of 1977: The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich Kavalier and Clay 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward 1976: J.R. by William Gaddis by Michael Chabon 1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone 2000: Interpreter of Maladies 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 2009: Let the Great World Spin The Hair of Harold Roux by Jhumpa Lahiri by Colum McCann by Thomas Williams 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 1998: American Pastoral by Philip Roth 2008: Shadow Country by Peter Matthiessen 1973: Chimera by John Barth 1997: Martin Dressler: The Tale of an 1972: The Complete Stories 2007: Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson American Dreamer 2006: The Echo Maker by Richard Powers by Flannery O’Connor by Steven Millhauser 1971: Mr. Sammler’s Planet by Saul Bellow 1996: Independence Day by Richard Ford 2005: Europe Central by William T. Volmann 1970: Them by Joyce Carol Oates 1995: The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 2004: The News from Paraguay 1969: Steps -

Visitor Experience Chris Abani Edward Abbey Abigail Adams Henry Adams John Adams Léonie Adams Jane Addams Renata Adler James Agee Conrad Aiken

VISITOR EXPERIENCE CHRIS ABANI EDWARD ABBEY ABIGAIL ADAMS HENRY ADAMS JOHN ADAMS LÉONIE ADAMS JANE ADDAMS RENATA ADLER JAMES AGEE CONRAD AIKEN DANIEL ALARCÓN EDWARD ALBEE LOUISA MAY ALCOTT SHERMAN ALEXIE HORATIO ALGER JR. NELSON ALGREN ISABEL ALLENDE DOROTHY ALLISON JULIA ALVAREZ A.R. AMMONS RUDOLFO ANAYA SHERWOOD ANDERSON MAYA ANGELOU JOHN ASHBERY ISAAC ASIMOV JOHN JAMES AUDUBON JOSEPH AUSLANDER PAUL AUSTER MARY AUSTIN JAMES BALDWIN TONI CADE BAMBARA AMIRI BARAKA ANDREA BARRETT JOHN BARTH DONALD BARTHELME WILLIAM BARTRAM KATHARINE LEE BATES L. FRANK BAUM ANN BEATTIE HARRIET BEECHER STOWE SAUL BELLOW AMBROSE BIERCE ELIZABETH BISHOP HAROLD BLOOM JUDY BLUME LOUISE BOGAN JANE BOWLES PAUL BOWLES T. C. BOYLE RAY BRADBURY WILLIAM BRADFORD ANNE BRADSTREET NORMAN BRIDWELL JOSEPH BRODSKY LOUIS BROMFIELD GERALDINE BROOKS GWENDOLYN BROOKS CHARLES BROCKDEN BROWN DEE BROWN MARGARET WISE BROWN STERLING A. BROWN WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT PEARL S. BUCK EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS OCTAVIA BUTLER ROBERT OLEN BUTLER TRUMAN CAPOTE ERIC CARLE RACHEL CARSON RAYMOND CARVER JOHN CASEY ANA CASTILLO WILLA CATHER MICHAEL CHABON RAYMOND CHANDLER JOHN CHEEVER MARY CHESNUT CHARLES W. CHESNUTT KATE CHOPIN SANDRA CISNEROS BEVERLY CLEARY BILLY COLLINS INA COOLBRITH JAMES FENIMORE COOPER HART CRANE STEPHEN CRANE ROBERT CREELEY VÍCTOR HERNÁNDEZ CRUZ COUNTEE CULLEN E.E. CUMMINGS MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM RICHARD HENRY DANA JR. EDWIDGE DANTICAT REBECCA HARDING DAVIS HAROLD L. DAVIS SAMUEL R. DELANY DON DELILLO TOMIE DEPAOLA PETE DEXTER JUNOT DÍAZ PHILIP K. DICK JAMES DICKEY EMILY DICKINSON JOAN DIDION ANNIE DILLARD W.S. DI PIERO E.L. DOCTOROW IVAN DOIG H.D. (HILDA DOOLITTLE) JOHN DOS PASSOS FREDERICK DOUGLASSOur THEODORE Mission DREISER ALLEN DRURY W.E.B. -

Download Winter 2015

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Winter 2015 JANUARY Introducing an original new voice in American fiction, “a wonderful group of stories . lyrical and honest in its look at modern American life. Buy this, and you will love it.”—Gus Van Sant White Man’s Problems Kevin Morris MARKETING “Life undermines the pursuit of success and status in these rich, bewildering The first self-published book that Grove has stories . a finely wrought and mordantly funny take on a modern predicament ever bought, already widely praised by a new writer with loads of talent.” —Kirkus Reviews Kevin Morris is already a well-known figure n nine stories that move between nouveau riche Los Angeles and the work- in the entertainment business, including ing-class East Coast, Kevin Morris explores the vicissitudes of modern life. coproducer of The Book of Mormon Whether looking for creative ways to let off steam after a day in court or national print and feature attention I enduring chaperone duties on a school field trip to the nation’s capital, the online promotion at kevinmorrisauthor.com heroes of White Man’s Problems struggle to navigate the challenges that accom- Twitter @KevinMorrisWMP pany marriage, family, success, failure, growing up, and getting older. The themes of these perceptive, wry and sometimes humorous tales pose philosophical questions about conformity and class, duplicity and decency, and the actions and meaning of an average man’s life. Morris’s confident debut strikes the perfect balance between comedy and catastrophe—and introduces a virtuosic new voice in American fiction. -

Paris Trout by Pete Dexter 1987

1989: Spartina by John Casey 2016: The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 1988: Paris Trout by Pete Dexter 2015: All the Light We Cannot See by A. Doerr 1987: Paco’s Story by Larry Heinemann 2014: The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 1986: World’s Fair by E. L. Doctorow 2013: Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2012: No prize awarded 2011: A Visit from the Goon Squad “Established in 1950, the National Book Award is an 1984: Victory Over Japan by Ellen Gilchrist by Jennifer Egan American literary prize administered by the National 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding Book Foundation, a nonprofit organization.” 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout - from the National Book Foundation website. 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao 1979: Going After Cacciato by Tim O’Brien by Junot Diaz 2017: Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward 1978: Blood Tie by Mary Lee Settle 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2016: The Underground Railroad by Colson 1977: The Spectator Bird by Wallace Stegner 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks Whitehead 1976: J.R. by William Gaddis 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 1975: Dog Soldiers by Robert Stone 2004: The Known World by Edward P. Jones 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay The Hair of Harold Roux 2003: Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride by Thomas Williams 2002: Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2001: The Amazing Adventures of 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward 1973: Chimera by John Barth Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 1972: The Complete Stories 2000: Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 2009: Let the Great World Spin by Colum McCann by Flannery O’Connor 1999: The Hours by Michael Cunningham 2008: Shadow Country by Peter Matthiessen 1971: Mr. -

Best and Worst of Times the Changing Business of Trade Books, 1975-2002

BEST AND WORST OF TIMES THE CHANGING BUSINESS OF TRADE BOOKS, 1975-2002 GAYLE FELDMAN NATIONAL ARTS JOURNALISM PROGRAM COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2003 The National Arts Journalism Program DIRECTOR Michael Janeway DEPUTY DIRECTOR and SERIES EDITOR Andr´as Sz´ant´o PRODUCTION DESIGN Larissa Nowicki MANAGING EDITORS Jeremy Simon Rebecca McKenna DATABASE RESEARCH ASSISTANT Vic Brand COPY EDITOR Carrie Chase Reynolds Cover photo courtesy of Stockbyte Copyright ©2003 Gayle Feldman All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of this work should be mailed to: NAJP, Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, 2950 Broadway, Mail Code 7200, New York, N.Y. 10027 This report was prepared with support from The Pew Charitable Trusts. Contents 1 Summary Findings 4 ...................................................................................................................... 2 The Changing Business: A Bird’s-Eye View 8 ........................ Introduction ........................................................................................................................ ..................................8 On the Origins and History of the Bestseller Species ........................................12 The Sea Change of the ’70s .................................................................................................................. -

Robert Ludlum's Bestselling Covert-One

Simon’s Cat JUST by Simon Tofi eld Added! The feline Internet phenomenon makes his way onto the page in this fi rst-ever book based on the popular animated series. Based on Simon Tofi eld’s animations that have taken YouTube by storm, SIMON’S CAT depicts and exaggerates the hilarious relationship between a man and his cat. The daily escapades of this adorable pet, which always involve demanding more food, and his exasperated but doting owner, come to life through simple black-and-white line drawings. With a huge fan following that is growing even larger by the day, SIMON’S CAT is set to become a major new comic creation. • Simon Tofi eld’s three short Simon’s Cat animations have received 21.9 million hits on YouTube in less than a year! • As seen by the success of the # 1 New York Times bestseller Dewey (GCP 2008), books about cats and their relationships with their owners are hugely popular with readers. • SIMON’S CAT will appeal to fans of I Can Has Cheezburger?, a feline-focused Web site that became a New York Times bestselling book (Gotham, 2008). • Simon’s Cat has won a number of awards, including YouTube’s Blockbuster Award and Best Comedy at the British Animation Awards. SEPTEMBER 2009 TRADE PAPERBACK 978-0-446-56066-1 • $12.99 / NCR 240 pages • 8 1/2 x 6 • 200 b/w images and cartoon strips • Humor/Pets • Rights: U.S., Philippines, Nonexclusive Open Market BUSINESS PLUS ●●●●● FALL 2009/WINTER 2010 ★ Ta b l e o f Co n T e n T s ★ GRAND CENTRAL PUBLISHING HARDCOVER AMONG THIEVES David Hosp ......................................................................................................................................... -

SDM Fobguide17.Pdf

CONTENTS 4 Mayor’s Welcome 6 SD Humanities Council Welcome 7 Event Locations and Parking 8 A Tribute to Children’s and Young Adult Literature Sponsored by United Way, John T. Vucurevich Foundation, Northern Hills Federal Credit Union and First Bank & Trust 9 A Tribute to Fiction Sponsored by AWC Family Foundation 10 A Tribute to Poetry Sponsored by Brass Family Foundation 11 A Tribute to Non-Fiction Sponsored by South Dakota Public Broadcasting 12 A Tribute to Writers’ Support Sponsored by South Dakota Arts Council 13 A Tribute to History and Tribal Writing Sponsored by Home Slice Media and City of Deadwood 14 Presenters 24 Schedule of Events 30 Exhibitors’ Hall Who Was Nicholas Black Elk? Black Elk, or Heȟáka Sápa (1863-1950), was an Oglala Lakota vision- ary and healer whose messages about the unity of humanity and Earth were conveyed by John G. Neihardt in the book Black Elk Speaks. At age 9, Black Elk had his Great Vision on Black Elk Peak (then called Harney Peak), the highest natural point in South Dakota and the Black Hills, which many Lakota consider to be the center of the world. The cover photograph was taken by Neihardt in 1931 when Black Elk returned to the peak to pray. Photo courtesy of the John G. Neihardt Trust. For more information visit sdbookfestival.com or call (605) 688-6113. Times and pre- senters listed are subject to change. Changes will be announced on sdbookfestival.com, twitter.com/sdhumanities, facebook.com/sdhumanities and included in the Festival Sur- vivor’s Guide, a handout available at the Exhibitors’ Hall information desk in the Dead- wood Mountain Grand Event Center. -

Harper Collins Writing Guide

W r i t i n g g u i d e s • • 1 WritingBooks Guides for Course Adoption www.HarperAcademic.com C o M p osition • J o urn A L i s M • ei C r At V e W r i t i n G • p oetrY • s C r een W r i t i n G • B u s i n e s s W r i t i n G • W r itin G C A r e e r s • MMAG r A r , s t Y L e , r e f e r e n C e , A n d LA n G u AG e Index View Print Exit W r i t i n g g u i d e s • • 1 COMPO s t i O n On Writing Well C o n t e n t s : Introduction • Part I: Principles • The Transaction • Simplicity • Clutter • Style • The Audience • Words • Usage • Part II: Methods • Unity • The Lead and the Th e ClAssiC guide tO Writing Ending • Bits & Pieces • Part III: Forms • Nonfiction as Literature • Writing About People: nOnfiCtiOn The Interview • Writing About Places: The Travel Article • Writing About Yourself: The 30tH AnniversAry editiOn Memoir • Science and Technology • Business Writing • Sports • Writing about the Art: William Zinsser Critics and Columnists • Humor • Part IV: Attitudes • The Sound of Your Voice • Enjoy- ment, Fear and Confidence • The Tyranny of the Final Product • A Writer’s Decisions • Expanded and updated, the 30th anniversary Write as Well as You Can edition of this favorite of both teachers and students now contains three new chapters, and William Zinsser is a writer, editor and teacher. -

Katonah Village Library Adult Book Discussion Group - Title Selections

Katonah Village Library Adult Book Discussion Group - Title Selections 2017 The Aviator’s Wife by Melanie Benjamin Double Indemnity by James M. Cain The Bees by Laline Paull Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff Behold the Dreamers by Imbolo Mbue Funny Girl by Nick Hornby Brewster by Mark Slouka The Girls by Emma Cline Burgess Boys by Elizabeth Strout The Great Fire by Shirley Hazzard The Circle by Dave Eggers Neverhome by Laird Hunt City of Thieves by David Benioff The Postman Always Rings Twice by James M. Cain The Devil and Webster by Jean H. Korelitz Regeneration by Pat Barker Dodgers, A Novel by William Beverley The Sense of an Ending by Julian Barnes 2016 Ancient Light by John Banville Remarkable Creatures by Tracey Chevalier Birth of Venus by Sarah Dunant The Round House by Louise Erdrich Devotion of Suspect X by Keigo Higashino The Sellout by Paul Beatty Foreign Bodies by Cynthia Ozick A Star for Mrs. Blake by April Smith In the Kitchen by Monica Ali Still Life with Bread Crumbs by Anna Quindlen Little Bee by Chris Cleave The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen March by Geraldine Brooks Tell the Wolves I’m Home by Carol Rifka Brunt Native Speaker by Chang-Rae Lee The Water Knife by Paolo Baciagalupi Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf 2015 All That Is by James Salter The Marriage Plot by Jeffrey Eugenides The Art Forger by B.A. Shapiro Mr. Penumbra’s 24 Hour Book Store by Robin Sloan The Ask by Sam Lipsyte Mudbound by Hillary Jordan Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh Orphan Train by Christina Baker Kline A Brief History of the Dead by