Problems in Administering Local Records

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decoding the Civil War: Engaging the Public with 19Th Century Technology & Cryptography Through Crowdsourcing and Online Educational Modules

The Huntington Library, Art Collections & Botanical Gardens Proposal to the National Historic Publications and Records Commission Decoding the Civil War: Engaging the Public with 19th Century Technology & Cryptography through Crowdsourcing and Online Educational Modules Project Summary 1. Purposes and Goals of the Project The American Civil War is perpetually fascinating to many members of the public. The goal of this project is to use the transcription and decoding of Civil War telegrams to engage new and younger audiences using crowdsourcing technology to spark their curiosity and develop new critical thinking skills. The transcription and decoding will contribute to national research as each participant will become a “citizen historian” or “citizen archivist.” Thus the project provides a model for long-term informal and formal education programs and curricula as it can be used even after the transcription and decoding is completed as a teaching model for students in inquiry-based learning. The Huntington Library respectfully requests a two-year grant from the National Historic Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) to provide partial funding for a consortium project that draws together the expertise of four different organizations—The Huntington Library, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, North Carolina State University, and, through the University of Minnesota, Zooniverse.org (a non-profit devoted to citizen science)— each bringing unique expertise to a collaboration among libraries, museums, social studies education departments, and software developers with the following goals: 1) Engage new and younger audiences by enlisting their service as “citizen archivists” to accelerate digitization and online access to a rare collection of approximately 16,000 Civil War telegrams called The Thomas T. -

Louisville Kentucky During the First Year of the Civil

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY DURING THE FIRST YEAR OF THE CIVIL WAR BY WILLIAM G. EIDSON Nashville, Tennessee During the first eight months of 1861 the majority of Kentuckians favored neither secession from the Union nor coercion of the seceded states. It has been claimed that since the state opposed secession it was pro-Union, but such an assertion is true only in a limited sense. Having the same domestic institutions as the cotton states, Kentucky was con- cerned by the tension-filled course of events. Though the people of Kentucky had no desire to see force used on the southern states, neither did they desire to leave the Union or see it broken. Of course, there were some who openly and loudly advocated that their beloved commonwealth should join its sister states in the South. The large number of young men from the state who joined the Con- federate army attest to this. At the same time, there were many at the other extreme who maintained that Kentucky should join the northern states in forcibly preventing any state from withdrawing from the Union. Many of the moderates felt any such extreme action, which would result in open hostility between the two sections, would be especially harmful to a border state such as Kentucky. As the Daily Louisville Democrat phrased it, "No matter which party wins, we lose." 1 Thus moderates emphasized the economic advantages of a united country, sentimental attachment to the Union, and the hope of compromise. In several previous crises the country had found compromise through the leadership of great Kentuckians. -

MARCH-APRIL 1981 Light Spot on the Display Unit

WE MARCH-APRIL 1981 light spot on the display unit. be seen to locate a defect, a spe What's An orangewood stick is used cially designed fixture is used to as a pointer. The short then can flip the circuit board from one New be marked with an arrow stick side to the other. e r. To l o o k a t t h e d e f e c t m o r e Using the camera, 95 percent closely, the technician places the of the defects were repaired. The T h e N o r t h e r n I l l i n o i s Wo r k s h a s extension ring on the lens of the implementation of the infrared a new cost saving infrared cam camera and positions the camera camera system for diagnostic era system for locating defects in so that an area 1 '4 inches square testing realized a substantial circuit packs. around the problem area may be cost reduction savings during its The diagnostic testing system viewed. first year of use for semi-conduc consists of a camera, liquid ni If both sides of the board must tor store circuit packs alone. trogen to provide a stable base for temperature comparison and a cathode ray tube to display the image seen by the camera. Generally, there are four types of problem-causing shorts in cir cuit packs: defective compo nents, foreign debris, solder bridges and internal multi-layer board defects. Early data col lected with the new system indi cate that components are more .im \" \ i % M a r c u s O n a t e w i t h i n f r a r e d c a m e r a that provides color monitoring. -

Published Quarterly by the Society of American Archivists the American Archivist

Volume 40 Number 4 October 1977 The Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/40/4/499/2746303/aarc_40_4_vt85337u6182j81n.pdf by guest on 23 September 2021 American Archivist Published Quarterly by The Society of American Archivists The American Archivist C. F. W. Coker, Editor Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/40/4/499/2746303/aarc_40_4_vt85337u6182j81n.pdf by guest on 23 September 2021 Douglas Penn Stickley, Jr., Assistant Editor Thomas E. Weir, Jr., Editorial Assistant DEPARTMENT EDITORS Maygene Daniels, Reviews Thomas E. Weir, Jr., News Notes Elizabeth T. Edelglass, Bibliography Ronald J. Plavchan, The International Scene Clark W. Nelson, Technical Notes EDITORIAL BOARD Maynard J. Brichford (1975-78), University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign William N. Davis, Jr. (1975-78), California State Archives John A. Fleckner (1977-80), State Historical Society of Wisconsin Elsie F. Freivogel (1977-80), National Archives and Records Service David B. Gracy II (1976-79), Texas State Archives Lucile M. Kane (1976-79), Minnesota Historical Society Mary C. Lethbridge (1973-77), Library of Congress William L. Rofes (1973-77), IBM Corporation The Society of American Archivists PRESIDENT Robert M. Warner, University of Michigan VICE PRESIDENT Walter Rundell, Jr., University of Maryland TREASURER Mary Lynn McCree, University of Illinois at Chicago Circle EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Ann Morgan Campbell COUNCIL MEMBERS Frank G. Burke (1976-80), National Historical Publications and Records Commission J. Frank Cook (1974-78), University of Wisconsin David B. Gracy II (1976-80), Texas State Archives Ruth W. Helmuth (1973-77), Case Western Reserve University Andrea Hinding (1975-79), University of Minnesota J. -

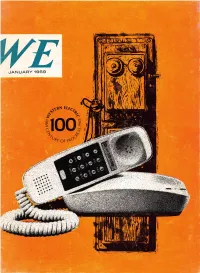

Century of Progress

® Western Electric: we make Bell telephones. We also make things for the network that keeps your calls from getting stuck in traffic. The Bell System telephone network has plenty millions of routes open throughout the Bell of traffic too. The number of phone calls increased n e t w o r k . I t ' s t h e m o s t a d v a n c e d c o m m u n i c a t i o n s last year to over 300 million a day. But, in case network in the world. And last year alone, we you haven't noticed, your call to almost any added over 2 million more dialing lines. place in the country goes through faster than That's why when you are traveling by phone, ever before. your call almost never hits a stop sign or a At Western Electric we have a hand in keeping red light. up this smooth service. We make and supply cable and call-switching equipment that keeps Western Efectric MANUFACTURING & SUPPLY UNIT OF THE BELL SYSTEM VLJI—. contents It All Started In Cleveland 2 Western Electric: a century of change We're Still on the Late Show 8 'Don Juan' sounds a beginning B u s t l e s t o M i n i - S k i r t s 1 2 Styles change, and so does womanpower Telegraphs and Guidance Systems 16 Since frontier days, a review of defense 1869 20 It was a year to remember Those Were the Days! 23 With modern appliances, housework's a breeze! There Are People Inside Those Buildings 27 The Hawthorne Studies and questions they answered O N C U E C O V E E : A n 1 8 8 2 M a g n e t o Wall set, the first phone built by 2 0 0 Ye a r s o f M e m o r i e s 30 Western Electric, and the modern Trimline® telephone mark 100 years Four men recall 'way back whens' of progress as Western Electric celebrates its centennial year. -

Thomas T. Eckert Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c86m3964 Online items available Thomas T. Eckert Papers Finding aid prepared by Olga Tsapina. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2014 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Thomas T. Eckert Papers mssEC 1-76 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Thomas T. Eckert Papers Dates: 1861-1877 Bulk dates: 1862-1867 Collection Number: mssEC 1-76 Creator OR Collector: Eckert, Thomas Thompson, 1825-1910 Extent: 76 volumes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains professional papers of Thomas T. Eckert (1825-1910), chiefly related to his duties as part of United States Military Telegraph Office during the Civil War. Language of Material: The records are in English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. Thomas T. Eckert Papers, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Provenance Purchased in part by the Library Collectors' Council from Seth Kaller, January 2012. -

Download File

3 Recasting the Information Infrastructure for the Industrial Age Richard R. John In the century and a quarter between the framing of the federal Con- stitution in 1787 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the United States evolved from a struggling commercial republic on the margins of Europe into one of the most powerful industrial nations in the world. Accompanying the rise of the United States to world power was a comparable transformation in the informational environment. The pe- riod witnessed an unprecedented expansion in printing and publishing, the emergence of information-intensive industries such as credit re- porting and life insurance, and the elaboration of major innovations in science, technology, and education. Each of these developments could furnish the theme for an essay on the role of information during the "long nineteenth century" that stretched from 1787 to 1914. Yet there was one development that may well have been the most fundamental. This was the recasting of the facilities for transmitting information cheaply, reliably, and on a regular basis throughout the country and around the world. Challenged by the size of the territory to be spanned, emboldened by a highly competitive institutional set- ting, and inspired by an irrepressible popular demand for more and better information, government administrators, business leaders, and ordinary Americans joined together in a grand collaborative project that would have been unimaginable in any prior age. The central institutions in the information infrastructure during this period—the Post Office Department, the Railway Mail Service, Western Union, and the Bell System—may seem rudimentary today. -

Graybar History

GraybarTHE Story From its humble beginnings in 1869 as Gray & Barton to becoming one of North America’s largest employee-owned companies, Graybar has served as the vital link in the supply chain working to the advantage of its suppliers and customers. WHO’s WHO IN GRAYBAR’s histORY PREAMBLE TO GRAYBAR’S HISTORY Like any good story, Graybar’s legendary history features a cast of characters who defined and transformed the company into what it is today. Enos Barton Born with the entrepreneurial spirit to one day lead a company, Enos Barton risked everything to co-found Gray and Barton, and built it from the ground up. George Shawk A superb craftsman and telegraph maker, George Shawk owned a small manufacturing shop in Cleveland, which he would later co-own with Enos Barton and eventually sell his share to Elisha Gray. Elisha Gray Fascinated by all things electric, Elisha Gray was a renowned inventor of SETTING THE more than 70 patents who partnered with Enos Barton to form Gray and Barton. Stage Anson Stager The general superintendent of raybar’s founding occurred One example of this was the the Western Union Telegraph during a period of U.S. history telegraph. The telegraph was an Company who helped Gray known as the Reconstruction, important tactical factor during the and Barton transform into the the post-Civil War era between 1865 Civil War, and it was also the fastest Western Electric Company through his integral business and 1877. way to transmit written messages relationships. As the Union was being restored over long distances during the post- Jay Gould and slavery was abolished, the nation war years. -

THE COMING of the TELEGRAPH to WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA by E

THE COMING OF THE TELEGRAPH TO WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA By E. DOUGLAS BRANCH University of Pittsburgh THE sonorous bass resounding through archways of sky: that I was its immemorial speech. But electricity in the late 1830's learned an American-invented argot of dots and dashes, of spaced impulses. A half-amused Congress in the last hour of its session voted $30,000 for a highway of copper thread between Washing- ton and Baltimore; and Samuel F. B. Morse, lately a professor of the arts of design, within fourteen hectic months saw the channel of his hopes spanning the forty miles. On May 24, 1844, in the Supreme Court room of the national capitol, a cluster of spectators surrounded an odd little machine with the inventor presiding at its key. Annie Ellsworth made her inspirational choice of the first message; and instantly in Baltimore a strip of tape was spelling out, "What hath God wrought !" In 1845 the line was extended to Philadelphia; and late in 1846 the magnetic keys were talking to Pittsburgh.' The optimist who built the first trans-Allegheny strand, from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, was one Henry O'Rielly,2 an Irish- born firebrand, sometime journalist and postmaster, a promoter of far-reaching vision but of myopic finances. Electricity was some- thing that happened when wires were attached to a Grove battery -a group of cells containing nitric and sulphuric acid. O'Rielly IThe indispensable history of the telegraph in America is Alvin F. Harlow, Old Wires and New Waves (N. Y., 1936), the bibliography of which lists the earlier volumes on the subject. -

O'reilly V. Morse

Working Paper Series No. 14010 O’Reilly v. Morse Adam Mossoff George Mason University School of Law May 2014 Hoover Institution Working Group on Intellectual Property, Innovation, and Prosperity Stanford University www.hooverip2.com DRAFT – May 2014 Please do not quote or distribute without prior permission O’REILLY V. MORSE Adam Mossoff I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 II. THE MORSE MYTH .................................................................................................................... 5 III. THE INVENTION OF THE ELECTRO-MAGNETIC TELEGRAPH .................................................... 13 IV. THE GREAT TELEGRAPH CASE ............................................................................................... 27 A. The Commercialization of Morse’s Patented Telegraph ............................................... 29 C. Morse v. O’Reilly in the District Court of Kentucky ..................................................... 40 1. O’Reilly’s Infringement of the “Principle” of Morse’s Patent ................................ 45 2. O’Reilly’s Failed Attempt to Invalidate Morse’s Patent for Lack of Novelty ........ 47 D. The Great Telegraph Case Continues: More Commercial, Legal & Public Battles ..... 52 V. THE MAKING OF THE MORSE MYTH ....................................................................................... 60 VI. CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................................... -

Anatomy of a Cipher

ANATOMY OF A CIPHER uring the American Civil War, Union generals He delegated much of the responsibility in Washington Dand civilian leaders sent millions of telegrams to to Major Thomas T. Eckert.2 coordinate and direct a society at war. Perhaps tens of Although Stager’s cipher was not terribly thousands of Union telegrams were sent in cipher during complex, it depended for success on absolute secrecy, the war to prevent rebels or their sympathizers from and the operators were told not to reveal the code to understanding the messages they may have intercepted. any person, including commanding officers and even Anson Stager developed the first telegraphic President Abraham Lincoln himself. A Civil War cipher used for military purposes during the Civil War.1 telegrapher described the system: “The principle of the Shortly after the war began, Governor William Dennison cipher consisted in writing a message with an equal of Ohio asked Stager to develop an encryption plan number of words in each line, then copying the words up for communication with the governors of Indiana and and down the columns by various routes, throwing in an Illinois. Major General George B. McClellan appointed extra word at the end of each column, and substituting Stager as superintendent of all telegraph lines in the other words for important names and verbs.”3 Department of the Ohio and asked Stager to develop The following example from April 1865 shows a field telegraph system to follow his army. The War the cipher in action in a telegram from Abraham Lincoln Department adopted Stager’s cipher system, and in in Washington to Major General Godfrey Weitzel in October 1861, Stager went to Washington to become Richmond. -

The Photographs of the President Arthur Yellowstone Expedition, 1883

The Photographs of the President Arthur Yellowstone Expedition, 1883 All of the photographs below are found in the digital collections of Southern Methodist University, DeGolyer Library, and are scans from printed work of the Arthur expedition, A Journey Through the Yellowstone National Park and Northwestern Wyoming 1883, by Frank J. Haynes. Some of the individual images may be found in other online galleries, including those of the National Library of Congress and the Jackson Hole Historical Society. The basic URL for the SMU collection with thumbnail images of the photos, as viewed on 1 August 2016 is: http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/search/collection/wes/searchterm/Folio- 2%20F722%20.J69%201883/mode/exact. The DeGolyer Library at SMU has generously made available the entire body of the published Haynes volume in PDF format. It is included here in its entirety, and includes both the text and photographs of the book. ~ rj w ~ I { d /0 ·~ .-4 Ui) ~ ~ I I JOURNEY -J.~~ 'J'HHOUGH 'fHE p~t2/ YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK AND NORTHWESTERN WYOMING. 1883. PHOTOGRAPHS OF PARTY AND SCENERY ALONG THE ROUTE TRAVELED, AND COPIES OF THE ASSOCIATED PRESS DISPATCHES SENT WHILST EN ROUTE. THE PARTY: CHESTER A. AR'l'HUR, President of the United States. RoBERT T. LINCOLN, Secretary of War. PHILIP H. SHERIDAN, Lieutenant General. GEORGE G. VEST, United States Senator. DAN. G. RoLLINS, Surrogate of New York. ANSON STAGER, Brigadier General, United States Volunteers. JNO. SCHUYLER CROSBY, Governor of Montana. M. V. SHERIDAN, Lieutenant Colonel and Military Secretary. JAMES F. GREGORY, Lieutenant Colonel and Aide-de-Camp.