ARO16: Digging Linlithgow's Past: Early Urban Archaeology on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Join Enter the Haggis on Their Tour of Scotland

APRIL 10-18, 2021 $2749.00PER PERSON LAND ONLY: $2374.00 PER PERSON (plus $569.00 US departure tax*) Join Enter The Haggis On their Tour of Scotland Day 1 USA to Ireland. Depart USA for overnight flight to Scotland. Dinner is served while in flight. April 10 Saturday Day 2 Glasgow-Stirling-Edinburgh. Arrive Glasgow Airport where you are met by your Driver & Guide. A day of Braveheart with a visit to Stirling, April 11 once known as the 'Key to Scotland', with its imposing position in the centre of the country, is home to Stirling Castle. For centuries this was Sunday the most important castle in Scotland and the views from the top make it easy to see why. Stirling Castle played an important role in the life of Mary Queen of Scots. Soak up the history and stunning views from the Wallace Monument, perched high on the Abbey Craig around where Wallace camped before his heroic battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, built in 1869 to commemorate Scotland’s hero. Continue to Edinburgh. Overnight Holiday Inn Express Day 3 Edinburgh Panoramic Tour. Today we enjoy a panoramic tour of Edinburgh. We pass by the Greyfriars Bobby, the loyal Skye Terrier who April 12 remained by his master's grave for fourteen years. Travel down the Royal Mile past St Giles Cathedral, the historic City Church of Edinburgh Monday with its famed crown spire. Also known as the High Kirk of Edinburgh, it is the Mother Church of Presbyterianism and contains the Chapel of the Order of the Thistle (Scotland's chivalric company of knights headed by the Queen). -

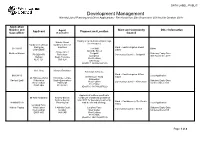

Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30Th September 2019 to 6Th October 2019

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30th September 2019 to 6th October 2019 Application Number and Ward and Community Other Information Applicant Agent Proposal and Location Case officer (if applicable) Council Display of an illuminated fascia sign Natalie Gaunt (in retrospect). Cardtronics UK Ltd, Cardtronic Service trading as Solutions Ward :- East Livingston & East 0877/A/19 The Mall Other CASHZONE Calder Adelaide Street 0 Hope Street Matthew Watson Craigshill Statutory Expiry Date: PO BOX 476 Rotherham Community Council :- Craigshill Livingston 30th November 2019 Hatfield South Yorkshire West Lothian AL10 1DT S60 1LH EH54 5DZ (Grid Ref: 306586,668165) Ms L Gray Maxwell Davidson Extenison to house. Ward :- East Livingston & East 0880/H/19 Local Application 20 Hillhouse Wynd Calder 20 Hillhouse Wynd 19 Echline Terrace Kirknewton Rachael Lyall Kirknewton South Queensferry Statutory Expiry Date: West Lothian Community Council :- Kirknewton West Lothian Edinburgh 1st December 2019 EH27 8BU EH27 8BU EH30 9XH (Grid Ref: 311789,667322) Approval of matters specified in Mr Allan Middleton Andrew Bennie conditions of planning permission Andrew Bennie 0462/P/17 for boundary treatments, Ward :- Fauldhouse & The Breich 0899/MSC/19 Planning Ltd road details and drainage. Local Application Valley Longford Farm Mahlon Fautua West Calder 3 Abbotts Court Longford Farm Statutory Expiry Date: Community Council :- Breich West Lothian Dullatur West Calder 1st December 2019 EH55 8NS G68 0AP West Lothian EH55 8NS (Grid Ref: 298174,660738) Page 1 of 8 Approval of matters specified in conditions of planning permission G and L Alastair Nicol 0843/P/18 for the erection of 6 Investments EKJN Architects glamping pods, decking/walkway 0909/MSC/19 waste water tank, landscaping and Ward :- Linlithgow Local Application Duntarvie Castle Bryerton House associated works. -

River Avon Catchment Profile

Published September 2011 River Avon catchment profile Introduction From its head waters near Greengairs, North Lanarkshire, the River Avon runs to enter the Firth of Forth at Grangemouth, draining a catchment of ~188km2. The catchment includes the settlements of Linlithgow, Bathgate, Armadale and Blackridge. Figure 1: River Avon catchment The catchment contains eight baseline1 surface water bodies, one of which is heavily modified and another artificial. The catchment also contains eight non-baseline water bodies. There are two groundwater bodies associated with the catchment. Water-dependent protected areas The catchment contains the following water-dependent protected areas which are all currently achieving their objectives: . Two drinking water protected areas . Two freshwater fish designation – River Avon and Union Canal . One urban waste water treatment directive sensitive area – River Avon (including Barbauchlaw Burn, Logie Water, Couston Water) Further information on the water bodies within the River Avon catchment can be found on the RBMP interactive map.The Forth Area Management Plan and other catchment profiles within the Forth sub basin district can be found on SEPA’s website. 1 A baseline water body is a river which drains a catchment greater than 10km2, lochs bigger than 0.5km2, all coastal waters out to three nautical miles, transitional waters such as estuaries and groundwaters. A non-baseline water body is a river or loch which falls below the size threshold. 1 Published September 2011 Classification and pressures summary -

Out in the Open Citation for Published Version: Moore, D 2012, out in the Open: Paraffin Harvester

Edinburgh Research Explorer Out In The Open Citation for published version: Moore, D 2012, Out In The Open: Paraffin Harvester. in Out in the Open: public Art in West Lothian. 1 edn, vol. 1, West Lothian Council Community Arts, Scotland, pp. Images pages pp. 11 and 48. Works cited pp. 18 and 43, Quotatation p. 33. Feature p. 49 and Acknowlegements p. 95. <http://lmmscache1.server.westlothian.gov.uk/media/downloaddoc/1799441/2195888/Out_in_the_Open_Pu blic_Art_book> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Out in the Open Publisher Rights Statement: © Moore, D. (2012). Out In The Open: Paraffin Harvester. In Out in the Open. West Lothian Council, Scotland. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 PUBLIC ART IN Firth of Forth M9 Harperrig VISITING PUBLIC ART IN WEST LOTHIAN Reservoir WEST LOTHIAN Rd 4 Each public art piece in this publication tells a story about the place in which it 3 A706 Grange A803 Blackness stands. -

Breastfeeding Friendly Awards/Healthy Start)

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC HEALTH AND CARE POLICY DEVELOPMENT AND SCRUTINY PANEL MATERNAL AND INFANT NUTRITION (BREASTFEEDING FRIENDLY AWARDS/HEALTHY START) REPORT BY DEPUTE CHIEF EXECUTIVE, COMMUNITY HEALTH AND CARE PARTNERSHIP A. PURPOSE OF REPORT To inform the Panel of the local venues with Baby Friendly Awards by providing facilities for breastfeeding; and to report on the uptake of Healthy Start Vouchers and free vitamins in NHS Lothian. B. RECOMMENDATION That the Panel: 1. supports the ongoing work required to implement these strategies, and 2. supports the recommendation that all major council/partnership centres work towards Breastfeeding Friendly Award status. C. SUMMARY OF IMPLICATIONS I Council Values x Focusing on our customers' needs x Making best use of our resources x Working in partnership II Policy and Legal (including None. Strategic Environmental Assessment, Equality Issues, Health or Risk Assessment) III Implications for Scheme of None. Delegations to Officers IV Impact on performance and Implementation of these strategies will have a performance Indicators positive impact on health and wellbeing indicators. V Relevance to Single SOA 2, 3, 4 We are better educated and have Outcome Agreement access to increased and better quality learning and employment opportunities. 1 SOA 5 Our children have the best start in life and are ready to succeed. SOA 6 We live longer, healthier lives and have reduced health inequalities. VI Resources - (Financial, Within current resources. Staffing and Property) VII Consideration at PDSP Reported to Health and Care PDSP annually. Relates to item 8, Action Note, Health and Care PDSP, 17/4/14. VIII Other consultations None. TERMS OF REPORT Breastfeeding Friendly Premises Within West Lothian, premises which have breastfeeding policies and provide suitable facilities are able to apply for the Breastfeeding Friendly Award. -

Full Results

West Lothian Schools' T&F Championships Grangemouth Stadium 12th June 2019 S1/S2 Boys Relay Heat 1 S1/S2 Boys Relay Heat 2 1 702 Bathgate 54.93 1 707 Linlithgow 53.11 2 701 Armadale 56.57 2 706 James Young 54.44 3 710 West Calder 57.57 3 704 Deans 54.94 4 709 St Margaret's 58.08 4 708 St Kentigern's 55.32 5 705 Inveralmond 60.05 5 703 Broxburn 55.48 S1/S2 Boys Relay Final 1 707 Linlithgow 53.96 8.0 2 704 Deans 55.01 7.0 3 706 James Young 55.24 6.0 4 702 Bathgate 56.15 5.0 5 708 St Kentigern's 56.32 4.0 6 703 Broxburn 56.79 3.0 S1/S2 Girls Relay Heat 1 S1/S2 Girls Relay Heat 2 1 703 Broxburn 55.84 1 709 St Margaret's 57.84 2 701 Armadale 57.33 2 707 Linlithgow 58.42 3 704 Deans 59.07 3 706 James Young 59.88 4 710 West Calder 60.58 4 708 St Kentigern's 60.07 5 702 Bathgate 61.55 5 705 Inveralmond 63.27 S1/S2 Girls Relay Final 1 703 Broxburn 57.05 8.0 2 701 Armadale 58.80 7.0 3 707 Linlithgow 59.43 6.0 4 706 James Young 60.81 5.0 5 710 West Calder 61.66 4.0 6 708 St Kentigern's 62.27 3.0 7 709 St Margaret's 62.69 2.0 8 704 Deans 63.62 1.0 S3 Girls Relay Heat 1 S3 Girls Relay Heat 2 1 709 St Margaret's 57.64 1 710 West Calder 58.72 2 707 Linlithgow 57.97 2 708 St Kentigern's 61.16 3 704 Deans 58.33 3 702 Bathgate 64.06 4 703 Broxburn 63.02 5 705 Inveralmond 63.21 S3 Girls Relay Final 1 704 Deans 58.53 8.0 2 709 St Margaret's 58.62 7.0 3 707 Linlithgow 58.72 6.0 4 710 West Calder 58.79 5.0 5 708 St Kentigern's 61.65 4.0 6 703 Broxburn 62.86 3.0 7 702 Bathgate 65.60 2.0 8 705 Inveralmond 65.85 1.0 S3 Boys Relay Heat 1 S3 Boys Relay Heat 2 1 -

Whitecross Community Action Plan 2014 - 2019 Contents

WHITECROSS COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN 2014 - 2019 CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 3 OUR COMMUNITY NOW 5 LIKES 6 DISLIKES 7 OUR VISION FOR THE FUTURE 8 MAIN STRATEGIES AND PRIORITIES 10 ACTION 14 MAKING IT HAPPEN 2 INTRODUCTION SES. 0 HOU R 42 OU UPS, OM L GRO FR OCA D H L NE IT . R W ONS U LD TI ET E ISA R H AN E RE G ER E OR W W T S S R RM W O . FO IE PP NT EY V U E 24 RV ER S V 8 COM WS SU NT D E MUNITY VIE D I N S AN , A RE 20 ST INGS ES U AKEHOLDER MEET ESS UT The plan will SIN F BU ITY UN be our guide for OMM 200 HE C what we PEOPLE ATTENDED T - as a community - try to make happen WHITECROSS COMMUNITY ACTION PLAN over the next 5 years. This Community Action Plan summarises community views about: • Whitecross now • the vision for the future of Whitecross • the issues that matter most to the community • our priorities for projects and action. WHITECROSS ACTION GROUP THANKS The preparation of the Action Plan has been guided by a local steering group – Whitecross Action Group - which brought together interested local TO EVERYONE residents that wanted to form a group that would help to shape the future of the area and take action to develop Whitecross in keeping with local WHO TOOK aspirations and needs. PART! LOCAL PEOPLE HAVE THEIR SAY The Action Plan has been informed by extensive community engagement carried out over a four month period from August 2013 to December 2013. -

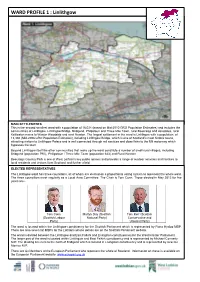

WARD PROFILE 1 : Linlithgow

WARD PROFILE 1 : Linlithgow MAIN SETTLEMENTS This is the second smallest ward with a population of 16,034 (based on Mid-2010 GRO Population Estimates) and includes the communities of Linlithgow, Linlithgow Bridge, Bridgend, Philpstoun and Three Mile Town, rural Beecraigs and Acredales, rural Kettleston mains to Wester Woodside and rural Newton. The largest settlement in the ward is Linlithgow with a population: of 13,360 (Mid-2008 GRO Population Estimates), including Linlithgow Bridge, which is one of Scotland’s most historic towns, attracting visitors to Linlithgow Palace and is well connected through rail services and close links to the M9 motorway which bypasses the town. Beyond Linlithgow itself the other communities that make up the ward constitute a number of small rural villages, including Bridgend (population 790), Philipstoun / Three Mile Town (population 643) and Rural Newton. Beecraigs Country Park is one of West Lothian’s key public spaces and provides a range of outdoor activities and facilities to local residents and visitors form Scotland and further afield. ELECTED REPRESENTATIVES The Linlithgow ward has three councillors, all of whom are elected on a proportional voting system to represent the whole ward. The three councillors meet regularly as a Local Area Committee. The Chair is Tom Conn. Those elected in May 2012 for five years are:- Tom Conn Martyn Day (Scottish Tom Kerr (Scottish (Scottish Labour National Party) Conservative and Party) Unionist Party) The ward is located within the Linlithgow constituency for the Scottish Parliament which is represented by Fiona Hyslop MSP. There are also seven list MSPs for the Lothians whose details are on the Scottish Parliament website. -

Public Council Executive Taxi Stances Report by Head Of

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC COUNCIL EXECUTIVE TAXI STANCES REPORT BY HEAD OF CORPORATE SERVICES A. PURPOSE OF REPORT To provide the Council Executive with an update on the proposals to designate a number of taxi stances and remove a stance which is no longer and to consider what action should now be taken regarding the proposals. B. RECOMMENDATION That the Council Executive approves: 1. The designation of the taxi stances referred to in the advertisement contained in Appendix 1 of this report and the removal of the larger of the two stances at West Main Street, Broxburn referred to therein and shown in Appendix 6 of this report; and 2. The initiation of statutory procedures to introduce a weekday day-time loading bay (6am-6pm, Mon-Fri) at the location of the taxi rank in High Street, Linlithgow. 3. The initiation of statutory procedures to amend the existing traffic regulation orders for Broxburn, Livingston and Linlithgow to prohibit waiting by vehicles other than taxis in designated taxi ranks. C. SUMMARY OF IMPLICATIONS I Council Values Focusing on our customers' needs Being honest open and accountable Working in partnership II Policy and Legal (including Section 19 of the Civic Government (Scotland) Strategic Environmental 1982 Assessment, Equality Issues, Health or Risk Assessment) III Implications for Scheme of None Delegations to Officers IV Impact on performance and None performance Indicators V Relevance to Single None Outcome Agreement 1 VI Resources - (Financial, Financial - The cost of advertising the proposal Staffing and Property) to designate stances was £642.34. Signs and markings are estimated to cost £200-£300 per stance. -

Investigating Explore Important Themes from Scotland’S History

A royal palace and military stronghold, where pupils can INVESTIGATING explore important themes from Scotland’s history. STIRLING CASTLE Information for teachers EDUCATION INVESTIGATING HISTORIC SITES: SITES 2 stirling castle Welcome to Stirling Castle Contents Stirling Castle is one of Scotland’s most Special activities for schools P4 magnificent, built on a rocky outcrop There are many activities programmed Supporting learning and commanding a view for many to take place every year for schools at and teaching miles around. It was built as an almost Stirling Castle. In the past, activities impregnable fortification, and visitors have included storytelling with P6 can explore many aspects of its long puppets for early years groups, art Integrating a visit with military history, particularly during the activities based on decoration in classroom studies Wars of Independence in the 1300s. the castle and two-site events at But it was also an important and Bannockburn and Stirling. P8 luxurious royal palace. Visitors today can Timeline gain an insight into the life of Scotland’s Visit the Historic Scotland website royal court, especially that of James V. to download this year’s Schools Programme. P10 Using this pack Stirling Castle: www.historic-scotland.gov.uk This resource pack is designed for a historical overview In addition to events organised by teachers planning to visit Stirling Castle Historic Scotland, handling boxes are with their pupils. It includes: P12 available for the use of pupils free of Themed teacher-led tours • Suggestions for how a visit to charge at the Regimental Museum of Stirling Castle can support delivery the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, P13 of the Curriculum for Excellence situated within the castle. -

Linlithgow Ward Plan

MULTI-MEMBER WARD OPERATIONAL PLAN FOR LINLITHGOW 2014-2017 Working together for a safer Scotland Contents Foreword 1 Introduction 2 Linlithgow Ward Profile 3 Local Operational Assessment 6 Achieving Local Outcomes 7 Priority Setting 8 SFRS Resources in West Lothian 9 Priorities, Actions and Outcomes 11 1. Local Risk Management and Preparedness 11 2. Reduction of Accidental Dwelling Fires 13 3. Reduction in Fire Casualties and Fatalities 15 4. Reduction of Deliberate Fire Setting 17 5. Reduction of Fires in Non-Domestic Properties 19 6. Reduction in Casualties from Non-Fire Emergencies 21 7. Reduction of Unwanted Fire Alarm Signals 23 Review 25 Feedback 25 Glossary of Terms 26 LINLITHGOW Multi Member Ward Operational Plan 2014-17 FOREWORD Welcome to the Scottish Fire & Rescue Services (SFRS) Operational Plan for the Local Authority Multi Member Ward Area of Linlithgow. This plan is the mechanism through which the aims of the SFRS’s Strategic Plan 2013 – 2016 and the Local Fire and Rescue Plan for West Lothian 2014-2017 are delivered to meet the agreed needs of the communities within the Linlithgow ward area. This plan sets out the priorities and objectives for the SFRS within the Linlithgow ward area for 2014 – 2017. The SFRS will continue to work closely with our partners in the Linlithgow ward area to ensure we are all “Working Together for a safer Scotland” through targeting risks to our communities at a local level. This plan is aligned to the Community Planning Partnership structures within West Lothian. Through partnership working, we aim to deliver continuous improvement in our performance and effective service delivery in our area of operations. -

64–66 HIGH STREET LINLITHGOW WEST LOTHIAN 64–66 High Street, Linlithgow, West Lothian

64–66 HIGH STREET LINLITHGOW WEST LOTHIAN 64–66 High Street, Linlithgow, West Lothian Lot 1 A grade C listed double upper flat, together with an attached peacefully located mews cottage available to purchase as a whole or in two lots. Lot 1 – 66 High Street - Mews House Accommodation Sitting/dining room, kitchen with utility area, double bedroom with en-suite bathroom, mezzanine bedroom/ study, shower room. Driveway, large private garden Lot 2 – 64 High Street - Double Upper Flat Accommodation Sitting Room, Dining Room, Kitchen, Utility Room, three bedrooms, bathroom, wc. 2 Lot 1 SITUATION: GENERAL DESCRIPTION Located halfway between Edinburgh and Stirling, Linlithgow is Two charming properties both fully modernised including double one of the most historic areas in Scotland with Blackness Castle, glazing and gas central heating and accessed via a shared Linlithgow Palace, St Michael’s Church and Linlithgow Loch. entrance, available as a whole or in two lots. There is a strong sense of community and a thriving centre for everyday shopping where there are three super markets and a Lot 1 is a unique mews style house, which is attached to the number of independent retailers cater for everyday needs. rear of the flat, peacefully tucked away behind the main street with private parking and long garden grounds running directly to For the outdoor enthusiast Beecraigs Country Park is located just the rear of Linlithgow Palace Peel. The accommodation can be 3 miles south of Linlithgow and provides a wide range of leisure accessed via the shared entrance into the kitchen or privately by and recreational interests within its 370 hectare (913 acre) Country a set of French doors leading in to the main hall.