The Effect of Colonial Symbolism in Selected Works by Afro-Caribbean Writers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature Se Enfocará En Las Voces Y Puntos De Vista Del México De Hoy

PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature Se enfocará en las voces y puntos de vista del México de hoy El Festival ofrecerá apariciones singulares en la Ciudad de Nueva York de autores líderes y emergentes de México junto con más de 150 artistas e intelectuales de todo el mundo Salones, talleres, conversaciones y espectáculos se celebrarán en toda la Ciudad de Nueva York, del 25 de abril al 1 de mayo de 2016 Nueva York, NY (18 de febrero de 2016, actualizado el 7 de marzo de 2016) — Escritores de todo el mundo se reunirán en Nueva York para intercambios y debates transculturales durante el duodécimo PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature, del 25 de abril al 1 de mayo de 2016. Éste es uno de los festivales literarios más grandes del mundo, y el único de su tipo con un enfoque en los derechos humanos. El Festival cataliza conversaciones entre escritores, artistas, líderes del pensamiento y el público en general sobre una variedad de temas culturales y sociales con importancia actual. El Festival, titulado Renegociando las narrativas, explorará la rica cultura de México y los problemas sociales candentes del país. A través de una serie de eventos, el Festival invita al público a repensar narrativas ampliamente aceptadas sobre temas como la identidad nacional, la frontera y la migración, así como la corrupción sistemática y la libre expresión en el México de hoy. Algunos de los pensadores y autores más importantes de México analizarán estas ideas, entre ellos Carmen Boullosa, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Lydia Cacho, Yuri Herrera, Sabina Berman y Elena Poniatowska. -

PDF Download the Blind Assassin Pdf Free Download

THE BLIND ASSASSIN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Margaret Atwood | 656 pages | 03 Sep 2001 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781860498800 | English | London, United Kingdom The Blind Assassin PDF Book Yet, by the time I was pages deep, it was obvious that the speed Atwood set was what could be expected for the duration of the journey. Her husband, an industrialist with dubious sexual tastes view spoiler [ ie illegal in many jurisdictions hide spoiler ] and habits. Should I continue? To what extent is she shaped by circumstances beyond her control? Like The Handmaid's Tale , it is destined to become a classic. Stay in Touch Sign up. Dec 18, ISBN For now I guess I will bask in the rosy glow of youth for as long as I can, before everything I love withers and dies. The Blind Assassin succeeds on all these levels: historical fiction, mystery, love story, and fantasy. When you buy a book, we donate a book. Inspired by Your Browsing History. Lists with This Book. It includes everything that up to it. I guess EL James proves that. Michael Christie. As an old woman, Iris recalls the events and relationships of her childhood, youth and middle age, including her unhappy marriage to Toronto businessman Richard Griffen. The writing was really great, but everything else kind of bored me -- the characters, the plot, the novel within the novel within the novel. I loved her description of her grandmother: "The planning and decoration of this house were supervised by my Grandmother Adelia. View 2 comments. The Air You Breathe. Surely they would want to ensure the Griffen heir was Richard's. -

Thoughts on Marlon James's a Brief History of Seven Killings. in Middle

Thoughts on Marlon James's A Brief History of Seven Killings. In Middle Passage, a travelogue in which V. S. Naipaul revisits the Caribbean, the author is swept up by the voices of its inhabitants. As one taxi driver tells him, “Is only when you live here as long as me that you know the sort of animal it is’. And understanding exactly what sort of ‘animal’ Jamaica is remains at the heart of James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings. Like Middle Passage, James’s book is a whirlwind of different voices, intertwining and separating as the novel proceeds. Yet unlike Middle Passage there is no artful attempt to spare the darkness of what was once the heart of the slave trade. As one of James’s characters says when talking about Naipaul’s travelogue, ‘The beauty of how him write that sentence still lie to you as to how ugly [West Kingston] is’. Ostensibly A Brief History of Seven Killings is about the failed assassination of the reggae singer, Bob Marley, immediately before a peace concert organised by the socialist People’s National Party (PNP) in 1976. Marley was wounded but went on to play the concert. He left straight afterwards and did not return to Jamaica for two years. The gunmen were never brought to justice and their identities remain a mystery. Even before James’s novel, the fog of uncertainty surrounding these events had elevated them to mythical status. James takes the few facts that are known and runs with them, as any novelist worth his salt would. -

Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards

Cleveland Foundation 1422 Euclid Avenue, Suite 1300 Cleveland, Ohio 44115 216.861.3810 fax 216.861.2229 www.Anisfield-Wolf.org EMBARGOED UNTIL APRIL 4, 2019, at 8 p.m. EST A History of Fugitives, a Contemporary Native American Novel and Civil War Voices as Poetry Have All Won the 84th Annual Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards CLEVELAND (April 4, 2019) – The Cleveland Foundation today unveiled the winners of its 84th Annual Anisfield- Wolf Book Awards. Jericho Brown, a 2015 Anisfield-Wolf honoree, made the announcement. The 2019 recipients of the only national juried prize for literature that confronts racism and explores diversity are: • Andrew Delbanco, “The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War,” Nonfiction • Tommy Orange, “There There,” Fiction • Tracy K. Smith, “Wade in the Water,” Poetry • Sonia Sanchez, Lifetime Achievement “The new Anisfield-Wolf winners bring us fresh insights on race and diversity,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr., who chairs the jury. “This year, we honor a breakout novel that jars awake our notions of contemporary Native Americans, a book of exceptional poetry from the U.S. Poet Laureate and a brilliant history right on time to depict the moral stakes testing every American generation. All is capped by the lifetime achievement of Sonia Sanchez, poet and an architect of the Black Arts Movement.” Dr. Gates directs the Hutchins Center for African and African-American Research at Harvard University, where he is also the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor. Joining him in selecting the winners each year are poet Rita Dove, novelist Joyce Carol Oates, psychologist Steven Pinker and historian Simon Schama. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

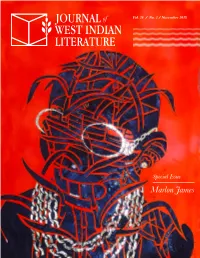

Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018

Vol. 26 / No. 2 / November 2018 Special Issue Marlon James Volume 26 Number 2 November 2018 Published by the Departments of Literatures in English, University of the West Indies CREDITS Original image: Sugar Daddy #2 by Leasho Johnson Nadia Huggins (graphic designer) JWIL is published with the financial support of the Departments of Literatures in English of The University of the West Indies Enquiries should be sent to THE EDITORS Journal of West Indian Literature Department of Literatures in English, UWI Mona Kingston 7, JAMAICA, W.I. Tel. (876) 927-2217; Fax (876) 970-4232 e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2018 Journal of West Indian Literature ISSN (online): 2414-3030 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Evelyn O’Callaghan (Editor in Chief) Michael A. Bucknor (Senior Editor) Lisa Outar (Senior Editor) Glyne Griffith Rachel L. Mordecai Kevin Adonis Browne BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Antonia MacDonald EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Baugh Victor Chang Alison Donnell Mark McWatt Maureen Warner-Lewis EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Laurence A. Breiner Rhonda Cobham-Sander Daniel Coleman Anne Collett Raphael Dalleo Denise deCaires Narain Curdella Forbes Aaron Kamugisha Geraldine Skeete Faith Smith Emily Taylor THE JOURNAL OF WEST INDIAN LITERATURE has been published twice-yearly by the Departments of Literatures in English of the University of the West Indies since October 1986. JWIL originated at the same time as the first annual conference on West Indian Literature, the brainchild of Edward Baugh, Mervyn Morris and Mark McWatt. It reflects the continued commitment of those who followed their lead to provide a forum in the region for the dissemination and discussion of our literary culture. -

Download Reading Guide

Oneworld Readers’ Guide A Brief History of Seven Killings Marlon James On December 3, 1976, just before the Jamaican general election and two days before Bob Marley was to play the Smile Jamaica Concert, seven gunmen stormed his house with machine guns blazing. The attack nearly killed the Reggae superstar, his wife and his manager. Marley would go on to perform at the free concert on December 5, but he left the country the next day, not to return for two years. Deftly spanning decades and continents and peopled with a wide range of characters – killers, gang members, politicians, FBI and CIA agents, journalists, conmen and even Keith Richards’ drug dealer – A Brief History of Seven Killings is the fictional exploration of that dangerous and unstable time and its bloody aftermath. About the Author Marlon James was born in Jamaica. He is the author of The Book of Night Women, which won the Day- ton Literary Peace Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. He is a professor of English Literature and Creative Writing at Macalester College, Minnesota, USA. Discussion Points 1. The novel’s structure invites the reader to play detective/journalist. In this sense, did you feel akin to Rolling Stone journalist Alex Pierce when reading A Brief History of Seven killings? Is there one character that you feel ties the novel together? 2. The majority of the characters in the novel are male, but it’s often Nina and her shape-shifting ways that readers are keen to discuss. Can her constant reinventing of herself, and her journey from Jamaica to America, be seen as belonging to any narrative tradition(s)? www.oneworld-publications.com Oneworld Readers’ Guide 3. -

Michael Cunningham Marlon James Cristina Henrí K N E a T V R O Presented in Association with N Y S I N Y Y a Z N O Y E U Bis L Quez S N O G N T L

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM PAID US Postage 2014 TX Houston ------ Non-Profit Org Non-Profit 2015 INPRINT 1002 No. Permit GEOFF DYER MARGARETT ROOT BROWN DEBORAH EISENBERG READING SERIES CRISTINA HENRÍQUEZ SEASON TICKETS MARGARETT ROOT BROWN $175 KAZUO ISHIGURO The purchase of season tickets, a portion of which is tax-deductible, helps make this series possible. INPRINT MARLON JAMES SEASON TICKET BENEFITS INCLUDE: ŝ Seating in the reserved section for each of the Main 1520 West eight readings. Seats held until 7:25 pm ŝ Signed copy of David Mitchell’s new novel The 77006 Houston, Texas INPRINT READING SERIES READING Bone Clocks available for pick up on the evening of his reading ŝ Access to the first-served “Season Subscriber” book-signing line DAVID MITCHELL ŝ Two reserved-section guest passes to be used ------ 2014 2015 during the 2014/2015 season ŝ Four free parking passes for the January–April ANTONYA NELSON 2015 readings for the Alley Theatre garage, across the street from the Wortham Center. ŝ Recognition as a “Season Subscriber” in each reading program KAREN RUSSELL 2014/2015 season tickets on sale! tickets season 2014/2015 To purchase season tickets on-line or for more MARY S ZYBIST details on season subscriber benefits, visit inprinthouston.org To pay by check, fill out the form on the back of this flap. KEVIN YOUNG PRESENTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH t h i s i s a b o o k m a r k BRAZOS BOOKSTORE AND UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON CREATIVE WRITING PROGRAM ZIP The Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series, now CITY in its 34th DEARseason, is made possible by the support of The Brown Foundation, Inc., Weatherford International, the NationalFRIENDS Endowment for the Arts: Art Works, and our season subscribers. -

Golden Man Booker Prize Shortlist Celebrating Five Decades of the Finest Fiction

Press release Under embargo until 6.30pm, Saturday 26 May 2018 Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist Celebrating five decades of the finest fiction www.themanbookerprize.com| #ManBooker50 The shortlist for the Golden Man Booker Prize was announced today (Saturday 26 May) during a reception at the Hay Festival. This special one-off award for Man Booker Prize’s 50th anniversary celebrations will crown the best work of fiction from the last five decades of the prize. All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of five specially appointed judges, each of whom was asked to read the winning novels from one decade of the prize’s history. We can now reveal that that the ‘Golden Five’ – the books thought to have best stood the test of time – are: In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul; Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively; The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje; Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel; and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. Judge Year Title Author Country Publisher of win Robert 1971 In a Free V. S. Naipaul UK Picador McCrum State Lemn Sissay 1987 Moon Penelope Lively UK Penguin Tiger Kamila 1992 The Michael Canada Bloomsbury Shamsie English Ondaatje Patient Simon Mayo 2009 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel UK Fourth Estate Hollie 2017 Lincoln George USA Bloomsbury McNish in the Saunders Bardo Key dates 26 May to 25 June Readers are now invited to have their say on which book is their favourite from this shortlist. The month-long public vote on the Man Booker Prize website will close on 25 June. -

2020 Lit Lineup Printable List of Books

Eye Opening Eye Witness 1. Barefoot Gen, Vol. 1 A Cartoon History of Hiroshima 1. Barracoon by Zora Neale Hurston (NF) Read Fifteen by Keiji Nakazawa (GN) 2. A Fire Story by Brian Fies (NF/GN) Make time for reading! 2. Evvy Drake Starts Over by Linda Holmes (F) 3. A Game For Swallows: To Die, To Leave, To Return by Zeina Join our community-wide initiative to read Exhalation: Stories Abirached (YA/GN) 3. by Ted Chiang (F) fifteen books throughout the year. 4. How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi (NF) 4. Indianapolis: The True Story of the Worst Sea Disaster in The book list was designed primarily for U.S. Naval History by Lynn Vincent & Sara Vladic (NF) 5. It Happened Like This: A Life in Alaska by Adrienne adults, although there are a number of books Lindholm (NF/AK) 5. Last Letters From Attu: The True Story of Etta Jones, Alas- from the children’s collection on this year’s ka Pioneer and Japanese POW by Mary Breu (NF/AK) 6. The Last Ocean: A Journey Through Memory and list so that families may participate together. Forgetting by Nicci Gerrard (NF) 6. Night by Elie Wiesel (B) To participate: 7. Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore: A Novel by Robin 7. One Long River of Song: Notes on Wonder by Brian Doyle Sloan (F) (NF) · Read a book from our list, in any category. 8. Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry (F) 8. The Only Plane in the Sky: An Oral History of 9/11 by · Report back that you’ve read a book from Garrett M. -

Spring Preview: 20 Books I Can't Wait to Read in 2019

This copy is for your personal non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies of Toronto Star content for distribution to colleagues, clients or customers, or inquire about permissions/licensing, please go to: www.TorontoStarReprints.com Spring Preview: 20 books I can’t wait to read in 2019 By Deborah Dundas Books Editor Fri., Jan. 18, 2019 The new year started with a new Marie Kondo series on Netflix helping people purge the things in their home that don’t give them joy. Well, I’ve got bad news for her. This spring’s new crop of books are clamouring to be read: stories from experienced and new writers, promising a wide array of perspectives and voices. From women’s fiction to social justice, short stories to mysteries, immigrant stories and tales of escape, books that explore the times we live in. We’ve picked some of the ones we think should join your to read list — we think they’ll get noticed, and give you joy. January Black Leopard, Red Wolf, by Marlon James, Doubleday Canada, 640 pages, $36.50 (DOUBLEDAY CANADA) The Golden Tresses of the Dead, Alan Bradley (Doubleday Canada, Jan. 22) This is the final book in the Cobourg- born writer’s Flavia de Luce series of mysteries, He’s had a heck of a story — starting to write only after retirement to fulfil a lifelong dream, and then being published around the world. Many readers will be sad to see Flavia go. Reproduction, Ian Williams (Random House of Canada, Jan. 22) Ian Williams is a prize-winning poet who now lives in Vancouver — but he grew up in Brampton. -

Narrative Technique in Marlon James's Novels

Vol. 5 No. 1 October 2020 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 Narrative Technique in Marlon James’s Novels Dr.J.MERCY VIJETHA Assistant Professor, Department of English Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa (A.P) Mr.R.BALAIAH Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of English Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa (A.P) Abstract Narrative Technique is a crucial tool for the novelist to write his/her literary work or work of art successfully. It is the means of producing a specific effect of a novel. Only with the employment of the right technique, the novelists would convey their ideas to the readers. It acts as the medium between life and art, which helps the novelist to interpret and transform reality. This creation involves the employment of several devices. It also makes the readers to discover and travel among other selves, other identities, and other variety of human adventures. It is the 'how' (technique) rather than the 'what' (subject) is instrumental in causing paradigm shifts, in founding literary schools, and in originating major literary trends. Hence narrative technique is not just an ornament or superimposed element upon the content to give it additional value but the intrinsic quality of the subject matter itself. Marlon James, a Jamaican novelist authored four novels John Crow’s Devil (2005), The Book of Night Women (2009), A Brief History of Seven Killings (2015), and Black Leopard, Red Wolf (2019) by adopting different techniques for each novel. The aim of the research paper is to explore how Marlon James accommodates contrasting ideas and themes in his novels by employing various methods.