Defining DSIEC's Relationships with Government and Political Parties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIG Template

Country Policy and Information Note Nigeria: Prison conditions Version 1.0 November 2016 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information The COI within this note has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. Feedback Our goal is to continuously improve the country policy and information we provide. Therefore, if you would like to comment on this document, please email the Country Policy and Information Team. -

A 13-Day Classic Wildlife Safari

58-25 Queens Blvd., Woodside, NY 11377 T: (718) 204-7077; (800) 627-1244 F: (718) 204-4726 E: [email protected] W: www.classicescapes.com Nature & Cultural Journeys for the Discerning Traveler THE INDIANAPOLIS ZOO CORDIALLY INVITES YOU ON AN EXCLUSIVE WILDLIFE SAFARI TO ZAMBIA AFRICA’S LESS DISCOVERED WILDERNESS NOVEMBER 2 TO 12, 2019 . Schedules, accommodations and prices are accurate at the time of writing. They are subject to change COUNTRY OVERVIEW ~ ZAMBIA Lions, leopards and hippos – oh my! On safari in Zambia, discover a wilderness of plains and rivers called home by some of the most impressive wildlife in the world. From zebra to warthog and the countless number of bird species in the sky and along the river banks, your daily wildlife-viewing by foot, 4x4 open land cruiser, boat and canoe gives you rare access to this untamed part of the world. Experience the unparalleled excitement of tracking leopard and lion on foot in South Luangwa National Park and discover the wealth of wildlife that inhabit the banks and islands of the Lower Zambezi National Park. At night, return to the safari chic comfort of your beautiful lodges where you can view elephant and antelope drinking from the river. YOUR SPECIALIST/GUIDE: GRAHAM JOHANSSON Graham Johansson is a Professional Guide and an accomplished wildlife photographer. He has been leading private and specialist photographic tours and safaris since 1994 in Botswana, his first love and an area he knows intimately–Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Graham was born and raised on a farm in Zambia, educated in Zimbabwe, and moved to South Africa to further his studies, train and pursue a career in tourism. -

Award Register for March 2021

LAGOS STATE PUBLIC PROCUREMENT LETTER OF AWARD REGISTEERED FOR MARCH 2021 S/N MDA PROJECT DESCRIPTION AMOUNT CONTRACTOR OFFICE OF DRAINAGE SERVICES & WATER PREPARATION OF THE LAGOS DRAINAGE MASTERPLAN 250,000,000.00 PHEMAN PENIEL CONSULTANTS LIMITED 1 CORPORATION FOR SECONDARY SYSTEMS MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC PLANNING AND ENGAGEMENT OF PROGRAM MANAGER FOR LAGOS 120,000,000.00 DEVTAGE CONSULTING LIMITED 2 BUDGET STATE DEVELOPMENT PLAN (LSDP) MINISTRY OF WOMEN AFFAIRS AND POVERTY SUPPLY OF DIESEL TO 18 (NOS.) SKILL ACQUISITION 9,249,840.00 C/R ACCESS 3 ALLEVIATION CENTRES FOR THE 1ST QUARTER OF YEAR 2021 LAGOS STATE INFRASTRUCTURE MAINTENANCE REINTEGRATION OF THE THREE (3) SATELLITE OFFICES 6,500,000.00 SAAB INVESTMENT LIMITED 4 AND REGULATORY AGENCY OF THE AGENCY (IKORODU, EPE BADAGRY AND THE HEAD OFFICE (LASIMRA) LAGOS STATE INFRASTRUCTURE MAINTENANCE CONSTRUCTION OF GATE HOUSE AND PLASTERING OF 4,000,000.00 SAAB INVESTMENT LIMITED 5 AND REGULATORY AGENCY THE CONSTRUCTED FENCE WALL AT THE BADAGRY SATELLITE OFFICE OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY GOVERNOR 3,400,000.00 MAINTENANCE OF ORNAMENTAL/DECORATIVE WATER 6 FOUNTAIN, OVERHEAD TANK AND FUMIGATION OF OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY GOVERNOR KOFLEX VENTURES PUBLIC WORKS CORPORATION 4,112,594.73 DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES AND 7 REPLACEMENT OF VOLP/IP/PABX SOLUTION AND ALL NETWORKS LTD ACCESSORIES AT PUBLIC WORKS CORPORATION LAGOS WASTE MANAGEMENT AUTHORITTY 208,997,148.94 LYNECREEK LIMITED 8 CAPPING OF OLUSOSUN & SOLOUS DUMPSITES PARASTATALS MONITORING OFFICE PURCHASE OF FURNITURE AND EQUIPMENT FOR 8,500,000.00 OCEANIC PLAMS SERVICES 9 PARASTATALS MONITORING OFFICE (PMO) FIRE SERVICE PROCUREMENT FOR THE PROVISION OF CLASSES A B 79,985,492.50 MESSRS. -

THE PUNTLAND STATE of SOMALIA 2 May 2010

THE PUNTLAND STATE OF SOMALIA A TENTATIVE SOCIAL ANALYSIS May 2010 Any undertaking like this one is fraught with at least two types of difficulties. The author may simply get some things wrong; misinterpret or misrepresent complex situations. Secondly, the author may fail in providing a sense of the generality of events he describes, thus failing to position single events within the tendencies, they belong to. Roland Marchal Senior Research Fellow at the CNRS/ Sciences Po Paris 1 CONTENT Map 1: Somalia p. 03 Map 02: the Puntland State p. 04 Map 03: the political situation in Somalia p. 04 Map 04: Clan division p. 05 Terms of reference p. 07 Executive summary p. 10 Recommendations p. 13 Societal/Clan dynamics: 1. A short clan history p. 14 2. Puntland as a State building trajectory p. 15 3. The ambivalence of the business class p. 18 Islamism in Puntland 1. A rich Islamic tradition p. 21 2. The civil war p. 22 3. After 9/11 p. 23 Relations with Somaliland and Central Somalia 1. The straddling strategy between Somaliland and Puntland p. 26 2. The Maakhir / Puntland controversy p. 27 3. The Galmudug neighbourhood p. 28 4. The Mogadishu anchored TFG and the case for federalism p. 29 Security issues 1. Piracy p. 31 2. Bombings and targeted killings p. 33 3. Who is responsible? p. 34 4. Remarks about the Puntland Security apparatus p. 35 Annexes Annex 1 p. 37 Annex 2 p. 38 Nota Bene: as far as possible, the Somali spelling has been respected except for “x” replaced here by a simple “h”. -

Camouflaged Cash: How 'Security Votes' Fuel Corruption in Nigeria

CAMOUFLAGED CASH How ‘Security Votes’ Fuel Corruption in Nigeria Transparency International (TI) is the world’s leading non-governmental anti- corruption organisation. With more than 100 chapters worldwide, TI has extensive global expertise and understanding of corruption. Transparency International Defence and Security (TI-DS) works to reduce corruption in defence and security worldwide. Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre (CISLAC) is a non-governmental, non-profit, advocacy, information sharing, research, and capacity building organisation. Its purpose is to strengthen the link between civil society and the legislature through advocacy and capacity building for civil society groups and policy makers on legislative processes and governance issues. Author: Matthew T. Page © 2018 Transparency International. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in parts is permitted, providing that full credit is given to Transparency International and provided that any such reproduction, in whole or in parts, is not sold or incorporated in works that are sold. Written permission must be sought from Transparency International if any such reproduction would adapt or modify the original content. Published May 2018. Every effort has been made to verify the accuracy of the information contained in this report. All information was believed to be correct as of May 2018. Nevertheless, Transparency International cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. CAMOUFLAGED CASH How ‘Security Votes’ Fuel Corruption in Nigeria D Camouflaged Cash: How ‘Security Votes’ Fuel Corruption in Nigeria EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ‘Security votes’ are opaque corruption-prone security funding mechanisms widely used by Nigerian officials. A relic of military rule, these funds are provided to certain federal, state and local government officials to disburse at their discretion. -

Prison Conditions

Country Policy and Information Note Nigeria: Prison conditions Version 1.0 November 2016 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information The COI within this note has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. Feedback Our goal is to continuously improve the country policy and information we provide. Therefore, if you would like to comment on this document, please email the Country Policy and Information Team. -

Sanctuary Retreats.Pdf

Sanctuary Retreats ............................ 4-5 Kenya ............................ 42 Olonana ............................ 43 Luxury ............................ 6-7 South Africa ............................ 44 Naturally ............................ 8-9 Makanyane Safari Lodge ............................ 45 Wilderness ............................ 10-11 Discovery ............................ 12-13 Tanzania ............................ 46-47 Cultural ............................ 14-15 Serengeti Migration Camp ............................ 48 Intimate ............................ 16-17 Kusini ............................ 49 Family ............................ 18-19 Saadani Safari Lodge ............................ 50 Bespoke ............................ 20-21 Saadani River Lodge ............................ 51 Swala ............................ 52 Cruises ............................ 22-23 Ngorongoro Crater Camp ............................ 53 China ............................ 24 Uganda ............................ 54 Yangzi Explorer ............................ 25 Gorilla Forest Camp ............................ 55 Egypt ............................ 26-27 Zambia ............................ 56 Sun Boat III ............................ 28 Sussi and Chuma ............................ 57 Sun Boat IV ............................ 29 Puku Ridge Camp ............................ 58 Nile Adventurer ............................ 30 Chichele Presidential Lodge ............................ 59 Zein Nile Chateau ............................ 31 Contact -

Prohealth Hmo Limited

PROHEALTH HMO LIMITED PROVIDER'S NETWORK S/N STATE/CITY SPECIALITY/PLAN PROVIDER ADDRESS ABIA 1 ABA ALL PLANS NEW ERA HOSPITAL 213/215 AZIKIWE ROAD ABA 2 ABA ALL PLANS LIVING WORD MISSION HOSPITAL 5/7 UMOCHAM ROAD ABA 3 ABA ALL PLANS SEVENTH DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH HOSPITAL UMUOBA ABA, ABIA STATE 4 ABA ALL PLANS LANDMARK HOSPITAL OLD ABA ROAD BY SAMEK, ABA. 5 ABA ALL PLANS MENDEL HOSPITAL & DIAGNOSTIC CENTRE NO 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA SOUTH, ABIA STATE. 6 ABA ALL PLANS IVORY HOSPITAL 175B,FAULKS ROAD, ABA, ABIA STATE 7 ABA ALL PLANS ROMALEX HOSPITAL 24, BRASS STREET, ABA, ABIA STATE 8 ABA ALL PLANS WIMPOLE CLINIC 87, ST MICHAEL'S ROAD, ABA, ABIA STATE 9 ABA ALL PLANS IMPACT HOSPITAL ABA 10 UMUAHIA ALL PLANS RESTORATION CLINIC EHIMIRI HOUSING ESTATE, UMUAHIA 11 UMUAHIA ALL PLANS OVERCOMER HOSPITAL ABA ROAD, AFTER MTN OFFICE (BY LEXVEE COMPUTERS),UMUAHIA. 12 UMUAHIA ALL PLANS MADONNA CATHOLIC HOSPITAL P.O.BOX 99, ABA ROAD, UMUAHIA UMUNGASI ROAD, ABA/OWERRI EXPRESS ROAD, BESIDE RHEMA 13 ABA Opticals LIVING WORD EYE CLINIC UNIVERSITY, ABA. 8-12 UMUKA ROAD, OFF 99 ABA-OWERRI ROAD, UMUNGASI, ABA, ABIA 14 ABA Opticals GLOBAL EYE CLINIC STATE ABUJA 15 CBD ALL PLANS LIMI SPECIALIST & MATERNITY HOSPITAL PLOT 541, BEHIND ICPC, CENTRAL AREA, ABUJA PLOT 528 PHASE AA1, LAYOUT, OPPOSITE HOLY FAMILY SCHOOL, 16 KUJE ALL PLANS JEDAM SPRING HOSPITAL ALONG FUNTAJ ROAD, KUJE 17 KUJE ALL PLANS ILA UNIVERSAL HOSPITAL PLOT MF1, AA1 LAYOUT, ALONG FUNTAJ INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL, KUJE GEORGE INNIH CRESCENT OFF IBRAHIM JALO WAZIRI RD, ZONE E, APO 18 APO DISTRICT ALL PLANS EXCEL SPECIALIST HOSPITAL LEGISLATIVE QUARTERS. -

Changing Dynamics in Contemporary West Africa's Political Economy

Africa, the Arabian Gulf and Asia: Changing Dynamics in Contemporary West Africa's Political Economy The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Akyeampong, Emmanuel K. 2011. "Africa, the Arabian Gulf and Asia: changing dynamics in contemporary west Africa's political economy." Journal of African Development 13 (1): 85-115. Published Version http://www.jadafea.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ JAD_vol13_ch5complete.pdf Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:14018060 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Africa, the Arabian Gulf and Asia: Changing Dynamics in Contemporary West Africa’s Political Economy* Emmanuel Akyeampong History Department, Harvard University 1730 Cambridge Street Cambridge, MA 02138 Email: [email protected] * The author is grateful to Dr. William Baah-Boateng for his assistance with the tables and figures in this paper, and to the two anonymous reviewers of this journal for their invaluable comments. ABSTRACT The last two to three decades have witnessed significant transformation in West Africa’s relations to the Arabian Gulf and Asia. While ties to countries such as Saudi Arabia are historic, economic liberalization since the 1980s has introduced new trading partners and some unexpected developments. The outcome of these recent developments can be startling: so in Ghana, for example, India and China have overtaken the United Kingdom, the former colonial power, in investments and the number of operating companies. -

Osinbajo Offers Scholarship to Gifted Physically

Ogun LG polls: APC opts for consensus, direct, indirect primaries By: Akorede Folaranmi State Caretaker Committee of some local governments, able to come up with solutions to particular venue when the chosen to consult the people the party, Tunde Oladunjoye, would then activate either the multiple candidates in some immediate past administration and the leaders, and the he All Progressives made this known in a chat with direct or indirect primaries for local governments. made arrangement whereby all primaries we are going to have Congress (APC) in newsmen, shortly after the other local governments that He added that the ruling party the names of 236 councillors and will not be conducted in one TOgun State says it will party's stakeholders meeting, couldn't arrive at an agreement would ensure that the local 20 local government chairmen corner of the house. adopt consensus, direct and held at the weekend inside the for a consensus candidate. government elections is free and were just held in a file, including "The constitution of the indirect primaries to choose its Presidential Lodge, Abeokuta, Oladunjoye, while saying fair, noting that the party's even other elective officers at the party states that such primaries c h a i r m a n s h i p a n d the Ogun state capital. the stakeholders meeting was primaries wouldn't be held in state and national level. for local government must be councillorship candidates for The party's spokesperson to ensure that none of the secret like it was done in the past. "But to the glory of God, we conducted at the local t h e f o r t h c o m i n g l o c a l explained that the party, having contestants in the LG elections "We are all in Ogun State, we are not having that kind of government headquarters and elections in the state. -

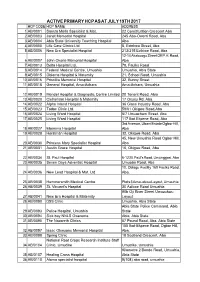

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS at JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS AT JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat. 22 Constitutition Crescent Aba 2 AB/0003 Janet Memorial Hospital 245 Aba-Owerri Road, Aba 3 AB/0004 Abia State University Teaching Hospital Aba 4 AB/0005 Life Care Clinics Ltd 8, Ezinkwu Street, Aba 5 AB/0006 New Era Specialist Hospital 213/215 Ezikiwe Road, Aba 12-14 Akabuogu Street Off P.H. Road, 6 AB/0007 John Okorie Memorial Hospital Aba 7 AB/0013 Delta Hospital Ltd. 78, Faulks Road 8 AB/0014 Federal Medical Centre, Umuahia Umuahia, Abia State 9 AB/0015 Obioma Hospital & Maternity 21, School Road, Umuahia 10 AB/0016 Priscillia Memorial Hospital 32, Bunny Street 11 AB/0018 General Hospital, Ama-Achara Ama-Achara, Umuahia 12 AB/0019 Mendel Hospital & Diagnostic Centre Limited 20 Tenant Road, Abia 13 AB/0020 Clehansan Hospital & Maternity 17 Osusu Rd, Aba. 14 AB/0022 Alpha Inland Hospital 36 Glass Industry Road, Aba 15 AB/0023 Todac Clinic Ltd. 59/61 Okigwe Road,Aba 16 AB/0024 Living Word Hospital 5/7 Umuocham Street, Aba 17 AB/0025 Living Word Hospital 117 Ikot Ekpene Road, Aba 3rd Avenue, Ubani Estate Ogbor Hill, 18 AB/0027 Ebemma Hospital Aba 19 AB/0028 Horstman Hospital 32, Okigwe Road, Aba 45, New Umuahia Road Ogbor Hill, 20 AB/0030 Princess Mary Specialist Hospital Aba 21 AB/0031 Austin Grace Hospital 16, Okigwe Road, Aba 22 AB/0034 St. Paul Hospital 6-12 St. Paul's Road, Umunggasi, Aba 23 AB/0035 Seven Days Adventist Hospital Umuoba Road, Aba 10, Oblagu Ave/By 160 Faulks Road, 24 AB/0036 New Lead Hospital & Mat. -

I Babafemi A. Badejo Rethinking Security Initiatives in Nigeria YINTAB BOOKS Lagos 2020

Babafemi A. Badejo Rethinking Security Initiatives in Nigeria YINTAB BOOKS Lagos 2020 i Yintab Books, a division of Yintab Ltd. Yintab Compound TOS Benson Estate Road, Agric Ikorodu, Lagos, Nigeria www.yintab.com Copyright © 2020 by Babafemi A. Badejo ISBN 978 9789799909 Paperback All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means whether electronic, mechanical, photocopying, scanning, placed on the web or in any form of recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments v Preface vi Foreword vii Prologue xv Introduction 1 Chapter One 3 General State of Insecurity All Over Nigeria 3 Chapter Two 6 Federal Inaction on General Insecurity 6 Chapter Three 9 Reactions to Federal Government's Inaction 9 Chapter Four 20 State Governments' Institutional Responses 20 Chapter Five 24 Operation Amotekun 24 Chapter Six 31 Popular Welcome for Operation Amotekun and Minor Irritations 31 Concluding Remarks 40 Index 46 iii Dedication Happy Birthday! Olumakinde Akinola Soname iv Acknowledgments was not thinking of writing a book, at least not within such a short time. I had written three different short pieces on Amotekun and I that was to have been it. When Makinde Soname called on me to say a few words at his birthday on any current issue of debate, I thought of speaking about corruption in Nigeria. Then he quipped: Why not Amotekun? He suggested the printing of the three pieces I had written as take away for guests at his birthday.