Who Is Killing the Tiger Panthera Tigris and Why?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

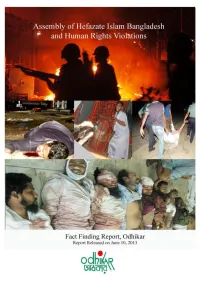

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Updated October 17, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44094 Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering India, Burma, and the Bay of Bengal. It is the world’s eighth most populous country with nearly 160 million people living in a land area about the size of Iowa. It is an economically poor nation, and it suffers from high levels of corruption. In recent years, its democratic system has faced an array of challenges, including political violence, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental strains, and Islamist militancy. The United States has a long-standing and supportive relationship with Bangladesh, and it views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. In relations with Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, the U.S. government, along with Members of Congress, has focused on a range of issues, especially those relating to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have at times sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades, as well as at the ballot box. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been in office since 2009, and her AL party was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament—in part because the BNP, led by Khaleda Zia, boycotted the vote. The BNP has called for new elections, and in recent years, it has organized a series of blockades and strikes. -

Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Stakeholderfor andAnalysis Plan Engagement Sund arban Joint ManagementarbanJoint Platform Document Information Title Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform Submitted to The World Bank Submitted by International Water Association (IWA) Contributors Bushra Nishat, AJM Zobaidur Rahman, Sushmita Mandal, Sakib Mahmud Deliverable Report on Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban description Joint Management Platform Version number Final Actual delivery date 05 April 2016 Dissemination level Members of the BISRCI Consortia Reference to be Bushra Nishat, AJM Zobaidur Rahman, Sushmita Mandal and Sakib used for citation Mahmud. Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform (2016). International Water Association Cover picture Elderly woman pulling shrimp fry collecting nets in a river in Sundarban by AJM Zobaidur Rahman Contact Bushra Nishat, Programmes Manager South Asia, International Water Association. [email protected] Prepared for the project Bangladesh-India Sundarban Region Cooperation (BISRCI) supported by the World Bank under the South Asia Water Initiative: Sundarban Focus Area Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... -

Bangladesh Other Countries and Regions Monitored

BANGLADESH OTHER COUNTRIES AND REGIONS MONITORED KEY FINDINGS RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE U.S. GOVERNMENT In 2016, the frequency of violent and deadly attacks against religious minorities, secular bloggers, intellec- USCIRF recommends that the U.S. government should: tuals, and foreigners by domestic and transnational provide technical assistance and encourage the Ban- extremist groups increased. Although the government, gladeshi government to further develop its national led by the ruling Awami League, has taken steps to inves- counterterrorism strategy; urge Prime Minister Sheikh tigate, arrest, and prosecute perpetrators and increase Hasina and all government officials to frequently and publicly denounce religiously divisive language and acts protection for likely targets, the threats and violence of religiously motivated violence and harassment; assist have heightened the sense of fear among Bangladeshi the Bangladeshi government in providing local govern- citizens of all religious groups. In addition, illegal land ment officials, police officers, and judges with training on appropriations—commonly referred to as land-grab- international human rights standards, as well as how to bing—and ownership disputes remain widespread, investigate and adjudicate religiously motivated violent particularly against Hindus and Christians. Other con- acts; urge the Bangladeshi government to investigate cerns include issues related to property returns and the claims of land-grabbing and to repeal its blasphemy law; situation of Rohingya Muslims. In March 2016, a USCIRF and encourage the Bangladeshi government to continue staff member traveled to Bangladesh to assess the reli- to provide humanitarian assistance and a safe haven for gious freedom situation. Rohingya Muslims fleeing persecution in Burma. BACKGROUND the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). -

Myth, Language, Empire: the East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 5-10-2011 12:00 AM Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 Nida Sajid University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Nida Sajid 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Cultural History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Sajid, Nida, "Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 153. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/153 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Myth, Language, Empire: The East India Company and the Construction of British India, 1757-1857 (Spine Title: Myth, Language, Empire) (Thesis format: Monograph) by Nida Sajid Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Nida Sajid 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners _____________________ _ ____________________________ Dr. -

CIFORB Country Profile – Bangladesh

CIFORB Country Profile – Bangladesh Demographics • Obtained independence from Pakistan (East Pakistan) in 1971 following a nine month civil uprising • Bangladesh is bordered by India and Myanmar. • It is the third most populous Muslim-majority country in the world. • Population: 168,957,745 (July 2015 est.) • Capital: Dhaka, which has a population of over 15 million people. • Bangladesh's government recognises 27 ethnic groups under the 2010 Cultural Institution for Small Anthropological Groups Act. • Bangladesh has eight divisions: Barisal, Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Rangpur, Sylhet (responsible for administrative decisions). • Language: Bangla 98.8% (official, also known as Bengali), other 1.2% (2011 est.). • Religious Demographics: Muslim 89.1% (majority is Sunni Muslim), Hindu 10%, other 0.9% (includes Buddhist, Christian) (2013 est.). • Christians account for approximately 0.3% of the total population, and they are mostly based in urban areas. Roman Catholicism is predominant among the Bengali Christians, while the remaining few are mostly Protestants. • Most of the followers of Buddhism in Bangladesh live in the Chittagong division. • Bengali and ethnic minority Christians live in communities across the country, with relatively high concentrations in Barisal City, Gournadi in Barisal district, Baniarchar in Gopalganj, Monipuripara and Christianpara in Dhaka, Nagori in Gazipur, and Khulna City. • The largest noncitizen population in Bangladesh, the Rohingya, practices Islam. There are approximately 32,000 registered Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, and between 200,000 and 500,000 unregistered Rohingya, practicing Islam in the southeast around Cox’s Bazar. https://www.justice.gov/eoir/file/882896/download) • The Hindu American Foundation has observed: ‘Discrimination towards the Hindu community in Bangladesh is both visible and hidden. -

“Crossfire:” Continued Human Rights Abuses by Bangladesh's Rapid

Bangladesh HUMAN “Crossfire” RIGHTS Continued Human Rights Abuses by Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion WATCH “Crossfire” Continued Human Rights Abuses by Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-767-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org May 2011 ISBN 1-56432-767-1 “Crossfire” Continued Human Rights Abuses by Bangladesh’s Rapid Action Battalion Map of Bangladesh ........................................................................................................................... ii Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations: .............................................................................................................. 9 Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 11 I. Killings and Other Cases of Abuse by RAB Since the Awami League Government Came to Power in 2009 ................................................................................................................................. -

The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch 'Where is Bhutan?': The Production of Bhutan's Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Kaul, N. This journal article has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form, subsequent to peer review and/or editorial input by Cambridge University Press in the Journal of Asian Studies. This version is free to view and download for private research and study only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Cambridge University Press, 2021 The final definitive version in the online edition of the journal article at Cambridge Journals Online is available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021911820003691 The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Manuscript ‘Where is Bhutan?’: The Production of Bhutan’s Asymmetrical Inbetweenness in Geopolitics Abstract In this paper, I interrogate the exhaustive ‘inbetweenness’ through which Bhutan is understood and located on a map (‘inbetween India and China’), arguing that this naturalizes a contemporary geopolitics with little depth about how this inbetweenness shifted historically over the previous centuries, thereby constructing a timeless, obscure, remote Bhutan which is ‘naturally’ oriented southwards. I provide an account of how Bhutan’s asymmetrical inbetweenness construction is nested in the larger story of the formation and consolidation of imperial British India and its dissolution, and the emergence of post-colonial India as a successor state. I identify and analyze the key economic dynamics of three specific phases (late 18th to mid 19th centuries, mid 19th to early 20th centuries, early 20th century onwards) marked by commercial, production, and security interests, through which this asymmetrical inbetweenness was consolidated. -

The British Expedition to Sikkim of 1888: the Bhutanese Role

i i i i West Bohemian Historical Review VIII j 2018 j 2 The British Expedition to Sikkim of 1888: The Bhutanese Role Matteo Miele∗ In 1888, a British expedition in the southern Himalayas represented the first direct con- frontation between Tibet and a Western power. The expedition followed the encroach- ment and occupation, by Tibetan troops, of a portion of Sikkim territory, a country led by a Tibetan Buddhist monarchy that was however linked to Britain with the Treaty of Tumlong. This paper analyses the role of the Bhutanese during the 1888 Expedi- tion. Although the mediation put in place by Ugyen Wangchuck and his allies would not succeed because of the Tibetan refusal, the attempt remains important to under- stand the political and geopolitical space of Bhutan in the aftermath of the Battle of Changlimithang of 1885 and in the decades preceding the ascent to the throne of Ugyen Wangchuck. [Bhutan; Tibet; Sikkim; British Raj; United Kingdom; Ugyen Wangchuck; Thirteenth Dalai Lama] In1 1907, Ugyen Wangchuck2 was crowned king of Bhutan, first Druk Gyalpo.3 During the Younghusband Expedition of 1903–1904, the fu- ture sovereign had played the delicate role of mediator between ∗ Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, 46 Yoshida-shimoadachicho Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, 606-8501, Japan. E-mail: [email protected]. 1 This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17F17306. The author is a JSPS International Research Fellow (Kokoro Research Center – Kyoto University). 2 O rgyan dbang phyug. In this paper it was preferred to adopt a phonetic transcrip- tion of Tibetan, Bhutanese and Sikkimese names. -

Bangladesh: Getting Police Reform on Track

BANGLADESH: GETTING POLICE REFORM ON TRACK Asia Report N°182 – 11 December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE LEGAL AND POLITICAL CONTEXT................................................................ 3 A. THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................3 B. THE POLITICAL MILIEU: OBSTACLES TO REFORM ........................................................................5 1. The bureaucracy...........................................................................................................................5 2. The military..................................................................................................................................6 3. The ruling elite.............................................................................................................................7 III. THE STATE OF THE POLICE ...................................................................................... 8 A. STRUCTURE AND ORGANISATION.................................................................................................8 B. THE BUDGET ...............................................................................................................................9 C. RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING ...................................................................................................10 -

Bhutan's Political Transition –

Spotlight South Asia Paper Nr. 2: Bhutan’s Political Transition – Between Ethnic Conflict and Democracy Author: Dr. Siegried Wolf (Heidelberg) ISSN 2195-2787 1 SSA ist eine regelmäßig erscheinende Analyse- Reihe mit einem Fokus auf aktuelle politische Ereignisse und Situationen Südasien betreffend. Die Reihe soll Einblicke schaffen, Situationen erklären und Politikempfehlungen geben. SSA is a frequently published analysis series with a focus on current political events and situations concerning South Asia. The series should present insights, explain situations and give policy recommendations. APSA (Angewandte Politikwissenschaft Südasiens) ist ein auf Forschungsförderung und wissenschaftliche Beratung ausgelegter Stiftungsfonds im Bereich der Politikwissenschaft Südasiens. APSA (Applied Political Science of South Asia) is a foundation aiming at promoting science and scientific consultancy in the realm of political science of South Asia. Die Meinungen in dieser Ausgabe sind einzig die der Autoren und werden sich nicht von APSA zu eigen gemacht. The views expressed in this paper are solely the views of the authors and are not in any way owned by APSA. Impressum: APSA Im Neuehnheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg [email protected] www.apsa.info 2 Acknowledgment: The author is grateful to the South Asia Democratic Forum (SADF), Brussels for the extended support on this report. 3 Bhutan ’ s Political Transition – Between Ethnic Conflict and Democracy Until recently Bhutan (Drukyul - Land of the Thunder Dragon) did not fit into the story of the global triumph of democracy. Not only the way it came into existence but also the manner in which it was interpreted made the process of democratization exceptional. As a land- locked country which is bordered on the north by Tibet in China and on the south by the Indian states Sikkim, West Bengal, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, it was a late starter in the process of state-building. -

Bangladesh: Political and Strategic Developments and U.S

Bangladesh: Political and Strategic Developments and U.S. Interests /name redacted/ Specialist in Asian Affairs June 8, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44094 Bangladesh: Political and Strategic Developments and U.S. Interests Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering the Bay of Bengal, dominated by low-lying riparian zones. It is the world’s eighth most populous country, with approximately 160 million people housed in a land mass about the size of Iowa. It is a poor nation and suffers from high levels of corruption and a faltering democratic system that has been subject to an array of pressures in recent years. These pressures include a combination of political violence, corruption, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental stress, and Islamist militancy. The United States has long-standing supportive relations with Bangladesh and views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. The U.S. government and Members of Congress have focused on issues related to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism among other issues as part of the United States’ bilateral relationship with Bangladesh. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades. Such mass protests are known as hartals in South Asia. The current AL government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament. Hasina has been in office since 2009.