Here Is a Super Abbreviated Version. Still Working on Tracking Down a More Detailed Resume Or Bio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMTRAK Return to Service Station Events

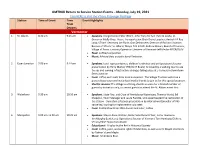

AMTRAK Return to Service Station Events – Monday, July 19, 2021 Click HERE to Visit the VTrans Passenger Rail Page Station Time of Event Time Event Highlights Train Departs Vermonter 1 St. Albans 8:30 am 9:15 am • Speakers: Congressman Peter Welch; John Tracy for Sen. Patrick Leahy; Lt. Governor Molly Gray; House Transportation Chair Diane Lanpher; Amtrak VP Ray Lang; VTrans’ Secretary Joe Flynn; Dan Delabruere, Director of Rail and Aviation Bureau of VTrans; St. Albans’ Mayor Tim Smith; Andrew Brown, Board of Trustees, Village of Essex Junction; Operation Lifesaver of Vermont-Jeff Medor-NECR/OLAV • Food: Coffee/tea/pastries. • Music: Minced Oats acoustic band-Tentative. 2 Essex Junction 9:00 am 9:44 am • Speakers: Local representatives, children’s activities and an Operation Lifesaver presentation by Perry Martel, VRS/OLVT Board, followed by a walking tour to see the up-and-coming infrastructure changes taking place at 5 Corners in Downtown Essex Junction • Food: coffee and treats from local businesses. The Village Trustees will issue a press release soon and invite local media friends to join us for this special occasion. • Shuttle services: The Village is offering shuttle services for a limited number of guests by invitation only, to permit guests to attend the St. Albans event first. 3. Waterbury 9:30 am 10:10 am • Speakers: State Rep. and Chair of Revitalizing Waterbury, Theresa Wood; Bill Shepeluk, Town Manager and Laura Parette, who spearheaded the restoration of the station. Operation Lifesaver presentation by Alex Schwartzmueller of VRS cancelled, looking for replacement volunteer. • Food: Cold Hollow Cider Mills donuts and cider; coffee 4. -

Citizen Initiatives Teacher Training Gas Taxes

DEFENDING AGAINST SECURITY BREACHES PAGE 5 March 2015 Citizen Initiatives Teacher Training Gas Taxes AmericA’s innovAtors believe in nuclear energy’s future. DR. LESLIE DEWAN technology innovAtor Forbes 30 under 30 I’m developing innovative technology that takes used nuclear fuel and generates electricity to power our future and protect the environment. America’s innovators are discovering advanced nuclear energy supplies nearly one-fifth nuclear energy technologies to smartly and of our electricity. in a recent poll, 85% of safely meet our growing electricity needs Americans believe nuclear energy should play while preventing greenhouse gases. the same or greater future role. bill gates and Jose reyes are also advancing nuclear energy options that are scalable and incorporate new safety approaches. these designs will power future generations and solve global challenges, such as water desalination. Get the facts at nei.org/future #futureofenergy CLIENT: NEI (Nuclear Energy Institute) PUB: State Legislatures Magazine RUN DATE: February SIZE: 7.5” x 9.875” Full Page VER.: Future/Leslie - Full Page Ad 4CP: Executive Director MARCH 2015 VOL. 41 NO. 3 | CONTENTS William T. Pound Director of Communications Karen Hansen Editor Julie Lays STATE LEGISLATURES Contributing Editors Jane Carroll Andrade Mary Winter NCSL’s national magazine of policy and politics Web Editors Edward P. Smith Mark Wolf Copy Editor Leann Stelzer Advertising Sales FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Manager LeAnn Hoff (303) 364-7700 Contributors 14 A LACK OF INITIATIVE 4 SHORT TAKES ON -

Putney Town Report

2019 Putney Town Report For the year ending June 30, 2019 Annual Town Meeting & Australian Ballot Vote Tuesday March 3, 2020 10:00 AM – 7:00 PM Putney Central School The Town of Putney Selectboard takes great pride in dedicating the 2019 Town Report to: JD and Jeanne McCliment In 2003 Jim (JD) and Jeanne were visiting Putney and found our local pub (formerly The Old Welsh Tavern), for sale. They decided to purchase and beautify the property and they turned it into a wonderful family run business (with their son, Emry as head chef). The pub has been a much-needed gathering spot for locals and visitors alike. The importance of having this vibrant social center in town cannot be underestimated and its closing leaves a big void. Jim and Jeanne have always been very community minded. Together with other business owners in town they founded the Putney Business Association. The idea behind this was to revitalize the profile of the town by trying to increase exposure and marketing to people living outside of town. They also worked on beautifying downtown by doing things such as installing and maintaining flower boxes along the Sacketts Brook bridge. In addition to this, Jim and Jeanne have been involved in raising money for various local organizations. Since 2015 Putney Charities has contributed over $84,000 to local non-profits with a focus on food and housing security and child well- being. Most of the funds were raised by selling rip tickets (pull tabs) at JD McCliment’s Pub, and ultimately the regulars who played. -

Gender Parity Index 2018 Report GENDER PARITY INDEX 2018 REPRESENTWOMEN Representwomen

Gender Parity Index 2018 Report GENDER PARITY INDEX 2018 REPRESENTWOMEN RepresentWomen A thriving democracy is within our reach, but we must level the playing field for women candidates across the racial, political, and geographic spectrum so that our nation’s rich diversity is reflected in our elected and appointed bodies. Electing more women to every level of government will strengthen our democracy by making it more representative, reviving bipartisanship and collaboration, encouraging a new style of leadership, and building greater trust in our elected bodies. The Gender Parity Index Report 2018 is an update to our State of Women’s Representation series, which documents and analyzes women’s representation in all fifty states and the U.S territories. It makes the case for structural changes that are necessary to achieve parity in our lifetimes. For additional information or to share your comments on this report, please contact: RepresentWomen 6930 Carroll Avenue, Suite 240 Takoma Park, MD 20912 www.representwomen.org [email protected] (301) 270-4616 Contributors: Cynthia Richie Terrell, with Antoinette Gingerelli and Johnathan Nowakowski Photos courtesy of iStockPhoto and WikiCommons. © Copyright February 2018. We encourage readers of this report to use and share its contents, but ask that they cite this report as their source. A note on data presented on women in politics: data on the representation of women in state legislatures, past and present, is courtesy of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. Similarly, much of the data on past women in elected office at all levels of government comes from the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. -

State to Main Legislative Update 2021

January 8, 2021 In This Issue: Civility: Is it Too Much to Ask? Not in Vermont State of the State Address Includes Focus on Economic Recovery Legislature Formalizes New Leadership Little Change in Committee Chair Assignments Federal Funding Flows into Vermont Explainer: Accessing Legislative Hearings Remotely Up Next In Case You Missed It Civility: Is it Too Much to Ask? Not in Vermont By Vermont Chamber President Betsy Bishop The contrast between Vermont and Washington, D.C., politics has never been more pronounced than it was this week. In Vermont, we ushered in a new legislative session with a trio of women leaders with new ideas, energy, and a profound sense of serving the State of Vermont to develop thoughtful, balanced public policy. Lt. Governor Molly Gray, Speaker of the House Jill Krowinski, and President Pro Tem Becca Balint begin this unusual, COVID-marked session with a pledge to work with Governor Phil Scott and his Administration to get Vermont’s economy on a path to recovery. While these leaders are from different parties, the spirit of cooperation and willingness to collaborate has always been present under the Golden Dome in Montpelier. What we witnessed on Wednesday in our nation’s capital was not only the total opposite, but it was also an attempt to subvert our core democratic principles. While I’m hopeful that President-elect Biden can unite us, it will take strong will to heed that call. I am grateful that I live in Vermont and work in the Vermont State House, and this year, while I will miss walking through the corridors among inspiring artwork, the Hall of Inscriptions, and the Cedar Creek Room, I still will still be fortunate to work on public policy with many people who share the same values. -

The Shopper 10-28-20

PRSRT STD U.S. POSTAGE 59 PAID POSTAL CUSTOMER FREE Years RESIDENTIAL CUSTOMER PERMIT #2 N. HAVERHILL, NH ECRWSSEDDMECRWSS ELECTION DAY fall back NOV. 03 your vote is Sunday, Nov. 1 at 2 a.m. your voice Your Local Community Newspaper OCTOBER 28, 2020 | WWW.VERMONTJOURNAL.COM VOLUME 59, ISSUE 22 Community creates “Black Lives Matter” mural BY JOE MILLIKEN member Laura Chapman as a long term, those conversations Other guests at the event in- The Shopper way to not act as a political state- will bring greater understand- cluded Senate Majority Leader ment, but rather to simply coun- ing, creating a community that is Becca Balint, Lieutenant Gov- PUTNEY, Vt. – After receiving ter and transform prejudice. genuinely inclusive.” ernor David Zuckerman, State approval from the Putney Se- Nearly 100 people took part The main purpose of the com- Representative Mike Mrowicki, lectboard, community members in the event throughout the mittee and the mural project is and Windham Southeast School recently united in front of the day, which was also attended by to ensure that all Putney resi- District Board Chairman David Putney Central School on West- Steffen Gillom, president of the dents, town employees, and visi- Schoales, and Vice Chairwoman minster West Road to proudly Windham County branch of tors receive equal treatment and of the School Board Anne Beek- paint a message for all to see: the National Association for the opportunity regardless of race, man. “Black Lives Matter.” Advancement of Colored Peo- color, religion, ancestry, national Understanding the impor- Manned with gallons of bright ple, who expressed to the par- origin, income, veteran status, tance of this positive message, yellow paint, brushes, and roll- ticipants and attendees that he sexual orientation, age, marital the school district board helped ers, adults and youth alike hoped that we can all continue or familiar status, disability, or initiate the event by issuing a teamed up to express their posi- to use art as a means for creat- gender identity and expression. -

Download PDF File

MOU NTA I N TIMES Vol. 50, No. 32 Fat FREE. Sugar FREE. Gluten FREE. Every page is FREE. Aug. 11-17, 2021 Blueberry power Blueberry season is wrapping up, but it's not too late! Grab a pint at a local farmers market or pick your own, then try this E-licious recipe. Page 23 Chris Karr to replace Claffey on Killington SB By Curt Peterson Killington Select Board member Chuck Claffey was about a half-year short of completing his first term on the Board when he sold his house and moved to Mendon, requiring him to resign from his seat. Chair Steve Finneran and Jim Haff (the remaining two Se- lect Board members) appointed a replacement for Claffey to Submitted avoid tie votes on town issues, Tuesday, Aug. 3. Prior to their Jane Ramos selection, Town Manager Chet Hagenbarth was authorized to solicit letters of inter- LOCAL LIBRARIAN est from residents who “My goal is to SELECTED TO SPEAK would like the job. IN RENO THIS FALL Four respondents — help keep the Submitted Killington Library Di- Mike Miller, Chris Karr, ship sailing in its Brian and Calista Budrow and their two young children moved to Rutland after Stay-to-Stay. rector Jane Ramos will Don Martin and Roger speak at a convention Rivera — expressed inter- current direction," in Reno, Nevada in Oc- est. After a discussion in tober. The conference executive session, Haff Karr said. The Budrow family finds their theme is “The biggest and Finneran chose Karr. little library.” “I like the stability the town government has right now, groove in the Rutland community Page 4 after a period of turmoil,” Karr told the Mountain Times. -

Rockingham Selectboard Hears Budget Increase Proposals From

57 FREE Years Check our ECRWSS Snow Report PRSRT STD US Postage Online PAID Permit #2 North Haverhill, NH National Syrup Day POSTAL CUSTOMER is December 17! www.VermontJournal.com Independently Owned & Locally Operated DECEMBER 12, 2018 | WWW.VERMONTJOURNAL.COM VOLUME 57, ISSUE 29 Quilt Group winners SPRINGFIELD, Vt. – The Quilt Group at First Congregational Church, UCC in Springfield is pleased to announce the results of the Quilters’ Raffle draw- ing, held Dec. 2, 2018. We sincerely thank everyone who supported the raffle. Congratulations to the following winners. Patricia Mazzacone of Mid- Santa meet and greet Sweet, colorful fun dleboro, Mass. won the lap quilt; Dianne Root of West Chazy, N.Y. won the snowman wall hanging; Jan Obdrzalek of Springfield won the batik table BELLOWS FALLS, Vt. – Kurn Hattin children greeted Santa at the American Jack spelled out his name with colorful candies on the office floor. Please runner; MaryJane Morin of Springfield won the placemats with napkins. Legion Post #37 in Bellows Falls to kick off the Christmas holiday. excuse his tummy ache since he tried to eat all of them! PHOTO PROVIDED PHOTO PROVIDED PHOTO PROVIDED Rockingham Selectboard hears budget increase proposals from town departments BY BETSY THURSTON gift Bennett a monetary thanks for Fire Department’s future needs and tical stock trucks. “Nothing fancy,” Gaetano Putignano asked when veterinary clinic, Susan Hammond The Shopper her almost 25 years of service with suggested two replacement trucks he explained. Griswold Drive was in the main- added, there is probably more traf- the town. to take the place of three currently Everett Hammond, director of tenance plan, and Doreen Aldrich fic than on Pleasant Valley Road. -

PDF | Download the Full Magazine

FIGHTING FEDERAL PRE-EMPTION PAGE 5 July/August 2016 I’m developing innovative technology that recycles nuclear fuel to generate electricity. With nuclear energy, we can have both reliable electricity and clean air. Leslie Dewan Technology Innovator, Forbes 30 Under 30 We Can’t Reduce CO2 Enough Without The world has set ambitious clean air goals and American innovators, like Bill Gates, Leslie Dewan at Transatomic Power and Jose Reyes at NuScale Power, are developing advanced nuclear energy technologies to reduce carbon emissions. Nuclear energy produces 63% of America’s carbon-free electricity and they know it has a distinct role to play to meet future energy and clean air goals. LEARN MORE nei.org/whynuclear #whynuclear CLIENT: NEI (Nuclear Energy Institute) PUB: State Legislatures Magazine RUN DATE: July/August SIZE: 7.5” x 9.875” Full Page VER.: Leslie - FP Ad 4CP: JULY/AUGUST 2016 VOL. 42 NO. 7 | CONTENTS A National Conference of State Legislatures Publication Executive Director William T. Pound Director of Communications Karen Hansen Editor NCSL’s national magazine of policy and politics Julie Lays Assistant Editor Kevin Frazzini FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Contributing Editor Jane Carroll Andrade What Great Leaders Do Page 14 SHORT TAKES PAGE 4 Online Magazine Ed Smith BY TIM STOREY Letters from members, along with connections, support, expertise Mark Wolf Good leaders have an abundance of skills. Great leaders have and ideas from NCSL Advertising Sales mastered these 10. Manager LeAnn Hoff TRENDS PAGE 7 (303) 364-7700 Which states have started replacing their share of the country’s [email protected] aging voting machines? We also have the latest on financial literacy Contributors Max Behlke for adults, the widening partisan gap and legislative “efficiency.” Jackson Brainerd Mindy Bridges Corina Eckl NEWSMAKERS PAGE 12 Pam Greenberg Katie Meehan A look at who’s making news under the domes Heather Morton Arturo Perez Budget Chaos Page 20 Jennifer Schultz BY ELAINE S. -

LGBTQ Victory Fund Staff

The Victory Fund creates viability. “It enables LGBTQ people to have a fighting chance at winning elected office.” U.S. REPRESENTATIVE RITCHIE TORRES (NY-15) Above: U.S. Representative Ritchie Torres On the Cover (left to right): Wheeling (WV) City Councilmember Rosemary Ketchum, Rhode Island state Senator Tiara Mack, Florida state Senator Shevrin Jones, Delaware state Senator Marie Pinkney, California Assemblymember Alex Lee, U.S. Representative Sharice Davids (KS-3), Florida state Representative Michelle Rayner, New Mexico state Senator Leo Jaramillo, U.S. Representative Mondaire Jones (NY-17), Pennsylvania state Representative Jessica Benham. Victory Fund 2020 Annual Report | 1 A Note From Mayor Annise Parker We began 2020 optimistic it would Yet we do not celebrate these be an unprecedented year for LGBTQ milestones solely because we made candidates and political power, but we history. We celebrate victories because had little idea just how unprecedented these leaders will ensure the interests of the year would be. The crises faced our community are considered in every by our nation and the world wreaked paragraph of every bill that comes havoc on our election plans and the across their desks. campaign strategies of our candidates, upending convention and propelling Many organizations faced enormous us to innovate. I’m proud to say that budget shortfalls and struggled to together, we met the challenge. continue important work. Yet you remained committed—supporting us Despite the tumult, you continued in whatever ways you could—which to support the organization and allowed us to keep providing candidates our mission, allowing us to lead the support from Victory Fund they have our candidates through a rapidly come to expect. -

2021 Vermont Statehouse Contact List 26 February 2021 This FOVLAP Listing Is Updated Annually in January

1 2021 Vermont Statehouse Contact List 26 February 2021 This FOVLAP listing is updated annually in January. Statehouse Governor Phil Scott Office of Governor Phil Scott 109 State St., Pavilion Montpelier, VT 05609 Phone: 802-828-3333 TTY: 800-649-6825 Fax: 802-828-3339 Office of Governor Phil Scott website homepage: https://governor.vermont.gov contact: https://governor.vermont.gov/contact https://governor.vermont.gov/contact/invite-the-governor Lt. Governor Molly Gray Office of the Lieutenant Governor 115 State St. Montpelier, Vermont 05633-5301 Office of the Lt. Governor website homepage: https://ltgov.vermont.gov contact: https://ltgov.vermont.gov/form/contact Becca Balint (Senate president pro tempore) 271 South Main St. Brattleboro, VT 05301 [email protected] Official website homepage https://protem.vermont.gov/ Jill Krowinski (House speaker) 115 State St. Montpelier, VT 05633-5301 (802) 828-2245 [email protected] Official website homepage: https://speaker.vermont.gov/ Sen. Alison Clarkson (Senate Majority Leader) 18 Golf Ave. Woodstock, VT 05091 [email protected] Rep. Emily Long (House Majority Leader) 239 Wiswall Hill Rd. Newfane, VT 05345 [email protected] 2 Senate Natural Resources & Energy Sen. Christopher Bray 115 State St. Montpelier, VT 05633-5301 [email protected] Sen. Richard Westman 2439 Iron Gate Rd. Cambridge, VT 05444 [email protected] Sen. Brian Campion 1292 West Rd. Bennington, VT 05201 [email protected] Sen. Dick McCormack 115 State St. Montpelier, VT 05633-5301 [email protected] Sen. Mark A. MacDonald 404 MacDonald Rd. -

Key State Legislative Contacts

Key State Legislative Contacts mac.mccutcheon@alhous Speaker of the House ALABAMA e.gov State Capitol Room 208 Governor Kay Ivey Phone: 334-261-0505 Juneau, AK 99801 600 Dexter Avenue Representative.Bryce.Edg Montgomery, AL 36130- Rep. Victor Gaston [email protected] 2751 11 South Union St Phone: 907-465-4451 Email via this portal Suite 519-G Phone: 334-242-7100 Montgomery, AL 36130 Rep. Steve Thompson [email protected] House Minority Leader Lt. Governor Will v State Capitol Room 204 Ainsworth Phone: 334-261-0563 Juneau, AK 99801 11 South Union St Representative.Steve.Tho Suite 725 Rep. Nathaniel Ledbetter [email protected] Montgomery, AL 36130 11 South Union St Phone: 907-465-3004 [email protected] Suite 401-G Montgomery, AL 36130 Rep. Lance Pruitt Senator Del Marsh nathaniel.ledbetter@alho House Minority Leader 11 South Union St use.gov State Capitol Room 404 Suite 722 Phone: 334-261-9506 Juneau, AK 99801 Montgomery, AL 36130 Representative.Lance.Pruit [email protected] Rep. Anthony Daniels [email protected] Phone: 334-261-0712 11 South Union St 907-465-3438 Suite 428 Senator Greg Reed Montgomery, AL 36130 Senator Cathy Giessel 11 South Union St anthony.daniels@alhouse. Senate President Suite 726 gov State Capitol Room 111 Montgomery, AL 36130 Phone: 334-261-0522 Juneau, AK 99801 [email protected] Senator.Cathy.Giessel@akl Phone: 334-261-0894 eg.gov ALASKA Phone: 907-465-4843 Senator Bobby Singleton Governor Mike Dunleavy 11 South Union St PO BOX 110001 Senator Lyman Huffman Suite 740 Juneau, AK 99811-0001 Majority Leader Montgomery, AL 36130 Email via this portal State Capitol Room 508 [email protected] Juneau, AK 99801 Phone: 334-261-0335 Lt.