Why Sponsors Should Worry About Corruption As a Mega Sport Event Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allianz Arena New Soccer Stadium Munich, Germany MAURER MSM®-Bearings, Protection Curtains

No. 01 VBA / 02_2005 1 / 2 Allianz Arena New Soccer Stadium Munich, Germany MAURER MSM®-bearings, protection curtains Figures and Facts Involvement of Maurer Soehne Location: Munich, Germany Supply and installation of 96 Spherical ® Owner: Allianz Arena Munich Ltd. MSM bearings, 5.500 kN, 45 mm Concessionaire: Soccer clubs: F.C. Bavaria movement, providing high load bearing Munich, TSV 1860 Munich capacity and low friction forces Contractor: Alpine Bau, Ltd. (concrete), Max Bögl Ltd. (steel) Supply and installation of 34.000 m² Architect: Herzog & de Meuron, Suisse movable sun- and noise protecting Consultants: ARUP Ltd., SSP Ltd. membrane with cable control system. The Total investment costs: 290 Mio. € installation was realised without scaffolding but by means of free-climbers. Design: Concrete bowl and steel truss roof structure, covered with a translucent and transparent membrane Utilisation: Pure soccer stadium with terraces directly bordering the pitch Floor space: 171.000 m² Number of seats: 66.000 Construction Time: autumn ‘02 – spring ‘05 No. 01 VBA / 02_2005 2 / 2 Fig. 1-3: installation of protection curtain system The remarkable roof structure is made of The transfer of the loads (up to 5.500 kN parabolic steel truss girders with a vertical loads on each support point) and the cantilevering length of 60 m, supporting the accommodation of occurring movements (up 35.000 m² transparent covering-cushions to 45 mm) is done by means of MAURER made of rhombic ETFE-elements. To provide Spherical bearings, equipped with a special sun- and noise protection during events, sliding material MSM®. These devices variable curtains are arranged below the roof combine high load bearing capacity with a structure. -

The Fc Bayern Munich Case Study

SCUOLA DELLE SCIENZE UMANE E DEL PATRIMONIO CULTURALE Corso di Laurea Magistrale in Management dello Sport e delle Attività Motorie Corporate Social Responsibility in the Sport industry: the FC Bayern Munich case study TESI DI LAUREA DI RELATORE Dott. Gaspare D’Amico Chiar. Prof. Dr. Salvatore Cincimino CORRELATORE ESTERNO Chiar. Prof. Dr. Jörg Königstorfer – Chair of Sport and Health Management at Technical University of Munich ANNO ACCADEMICO 2016 – 2017 INDEX ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………….1 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………...3 I. CHAPTER – CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 1. Evolving Concepts and Definitions of CSR………………………………..6 1.1 Criticism and Defensive theory of CSR……………………………….11 1.2 The origin of Stakeholder Theory……………………………………..13 1.3 Standard and certification……………………………………………..17 1.4 Evaluation and control………………………………………………...22 II. CHAPTER – CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY IN SPORTS INDUSTRY 2. Definition and general aspects of CSR in the sports industry…………......26 2.1 Stakeholders Model……………………………………………………33 III. CHAPTER – THE FC BAYERN MUNICH CASE STUDY 3. Use of Case Study Research………………………………………………50 3.1 Corporate Structure of FC Bayern Munich……………………………53 3.1.1 Ownership……………………………………………………….65 3.1.2 Management…………………………………………………….68 3.1.3 Team…………………………………………………………….77 3.2 Revenues and costs drivers of FC Bayern Munich……………………79 3.2.1 Revenues of Football club………………………………...…….81 3.2.1.1 Matchday…………………………………………..……..82 3.2.1.2 Broadcasting rights……………………………………….85 3.2.1.3 Commercial Revenues……………………………………90 -

Live Live Live

LIVE LIVE LIVE 30.09. 10:17 FK Viktoria Bohemians 30.09. 11:00 Fortuna Rot-Weiss 30.09. 11:00 Rot Weiss Essen VfL Bochum 30.09. 11:00 MSV Duisburg TSV Alemannia 30.09. 11:00 SC Fortuna Borussia 30.09. 11:30 CSKA Moscow Dinamo Moscow 30.09. 12:00 Granada Celta C + Liga 30.09. 12:00 FC Porto B FC Penafiel 30.09. 12:15 CAI Zaragoza Caja Laboral JSC Sport +6 30.09. 12:15 CF Belenenses CD Tondela 30.09. 12:30 Udinese Genova Sky Calcio 1 30.09. 12:30 AZ Alkmaar RKC Waalwijk Eredivisie 30.09. 13:00 Bbcu FC Muang Thong 30.09. 13:00 Skonto Riga FC Daugava 30.09. 13:00 FC Vestsjaelland AB Copenhagen 30.09. 13:30 Bochum Ingolstadt Sky Bundesliga 30.09. 13:30 1 FC Eintracht 30.09. 13:30 Germania Energie Cottbus 30.09. 13:30 Dynamo Dresden Erzgebirge Aue 30.09. 13:45 BSC Young Boys Servette Geneva 30.09. 14:00 Kartalspor Boluspor 30.09. 14:00 FC Anzhi Volga Nizhny 30.09. 14:00 VfL Bochum II MSV Duisburg II 30.09. 14:00 FSV Frankfurt II Wormatia Worms 1 of 7 30.09. 14:00 SpVgg Offenbacher 30.09. 14:00 FSV Mainz 05 II SV Waldhof 30.09. 14:00 TSV 1860 Munich FV Illertissen 30.09. 14:00 Valenciennes Marseille Sportitalia 1 30.09. 14:00 Silkeborg IF Aalborg BK 30.09. 14:00 Bayern Munich II FC Ismaning 30.09. 14:00 TSG Hoffenheim Bayern Alzenau 30.09. -

Live Live Live

LIVE LIVE LIVE 14.08. 10:18 Fc Slovan Liberec Fk Oez Letohrad 14.08. 10:47 Oakleigh Hume City 14.08. 10:47 SC Condor Bergedorf 85 14.08. 10:59 Fortuna TSV Alemannia 14.08. 10:59 TSG Hoffenheim Spvgg 14.08. 11:00 Navibank Sai Gon Hoang Anh Gia 14.08. 11:01 Rot-Weiss Rot Weiss Ahlen 14.08. 11:02 Borussia Wuppertaler SV 14.08. 11:03 Hamburger SV Hallescher FC 14.08. 11:03 VfL Bochum U19 Bayer 04 14.08. 11:04 MSV Duisburg Schalke 04 U19 14.08. 11:04 TB Neckarhausen Borussia 14.08. 11:04 FC Union Berlin VfL Oldenburg 14.08. 11:04 Bayern Munich TSV 1860 Munich 14.08. 11:07 Borussia FC Cologne U19 14.08. 12:00 Seongnam Ilhwa Ulsan Hyundai 14.08. 12:30 Heracles NAC Breda Eredivisie 14.08. 13:00 Werder Bremen VfL Osnabruck 14.08. 13:00 Hertha BSC Berlin VfL Wolfsburg 14.08. 13:15 Kilmarnock FC Hibernian FC 14.08. 13:30 ZFC Meuselwitz SV 14.08. 13:30 Ingolstadt FSV Frankfurt Sky Germany 14.08. 13:30 Duisburg Hansa Sky Germany 14.08. 13:30 VFC Plauen FC Magdeburg 1 of 5 14.08. 13:30 Berliner AK 07 Hallescher FC 14.08. 13:30 1860 München Erzgebirge Aue Sky Germany 14.08. 14:00 Lyngby BK AC Horsens 14.08. 14:00 FSV Frankfurt II Wormatia Worms 14.08. 14:00 Greuther Furth II TSV 1860 Munich 14.08. 14:00 Karlsruher SC II 1 FC Nuremberg 14.08. -

Live Live Live

LIVE LIVE LIVE 10.11. 17:00 Ethnikos Achnas Apoel Nicosia FC 10.11. 23:30 Club Atletico CD Once Caldas 11.11. 00:00 Ceara CE CRB AL 11.11. 09:00 Pohang Steelers Jeju United FC 11.11. 10:01 Paok Platanias 11.11. 10:03 FC Delta Tulcea CS Otopeni 11.11. 10:20 FK Viktoria Mas Taborsko 11.11. 10:30 FC Lokomotiv FC Anzhi 11.11. 10:56 Arenas-Gualda, Kern, Robin 11.11. 11:00 Borussia Bayer 04 11.11. 11:00 FSV Mainz 05 FC Augsburg 11.11. 11:00 Eintracht FSV Frankfurt 11.11. 11:00 1 FC Cologne VfL Bochum 11.11. 11:00 Hallescher FC VfL Osnabruck 11.11. 11:00 Fortuna Borussia 11.11. 12:00 Hercules CF Las Palmas UD 11.11. 12:00 CF Villarreal Murcia Al Jazeera +10 11.11. 12:00 Shirak Gyumri FC Mika FC 11.11. 12:00 Valladolid Valencia C + Liga 11.11. 12:00 Maritimo Funchal CD Santa Clara 11.11. 12:15 Real Madrid Bizkaia Bilbao Arena Sport 2 11.11. 12:15 FC Arouca FC Porto B 11.11. 12:30 Palermo Sampdoria Sky Calcio 1 11.11. 12:30 MSK Zilina AS Trencin 1 of 8 11.11. 12:30 Vitesse Twente Eredivisie 1 11.11. 12:30 MKS Flota Zawisza 11.11. 12:45 FC Rubin Kazan FC Kryliya 11.11. 13:00 Ranheim IL Strommen IF 11.11. 13:00 OFK Belgrade FK Red Star 11.11. 13:00 Kartalspor Konyaspor 11.11. 13:00 Gaziantepspor Genclerbirligi 11.11. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Mechtel, Mario; Brändle, Tobias; Stribeck, Agnes; Vetter, Karin Conference Paper Red Cards: Not Such Bad News For Penalized Guest Teams Beiträge zur Jahrestagung des Vereins für Socialpolitik 2010: Ökonomie der Familie - Session: Labor Market and Entrepreneurs: Empirical Studies, No. B8-V1 Provided in Cooperation with: Verein für Socialpolitik / German Economic Association Suggested Citation: Mechtel, Mario; Brändle, Tobias; Stribeck, Agnes; Vetter, Karin (2010) : Red Cards: Not Such Bad News For Penalized Guest Teams, Beiträge zur Jahrestagung des Vereins für Socialpolitik 2010: Ökonomie der Familie - Session: Labor Market and Entrepreneurs: Empirical Studies, No. B8-V1, Verein für Socialpolitik, Frankfurt a. M. This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/37282 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

The People’S Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany Alan Mcdougall Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05203-1 - The People’s Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany Alan McDougall Index More information Index Abgrenzung, 59, 87, 91, 117, 177, 289–90, Beckenbauer, Franz, 91, 118 295 Becker, Boris, 119 Abramian, Levon, 150 Behrendt, Helmut, 78 AC Milan, 49–50, 75, 85, 337 Benedix, Karl-Heinz, 163 Adidas, 121, 278, 293–4, 297, 304 Bensemann, Walter, 16 Adorno, Theodor, 12 Berger, Jörg, 128, 134–5 AFC Wimbledon, 330 Berlin Wall, 8, 63, 106, 128, 131, 144, 174, Ajax, 111, 114–15, 141, 190 182, 242, 288, 315, 332 Aktivist Brieske-Senftenberg, 138 Berliner FC Dynamo (BFC), 3, 25, 27–8, Alltagsgeschichte, 28, 252, 264 53, 90, 92–3, 104, 110, 126–7, 144, amateurism, 56, see also professionalism 156, 186, 188, 201, 205, 210, 212, and GDR football, 60, 67, 69, 105, 162, 220, 270, 320, 326 166 after the Wende, 3, 314, 317, 321, 325, and the DFB, 16–17, 34 327, 330–1 and the Olympic Games, 84 and doping, 95 Andone, Ioan, 336 and fan clubs, 191–3, 195–8 Archetti, Eduardo, 91 and hooliganism, 208, 211, 220, 314, 328 Argentinian football, 336 and the end of the GDR, 241–4 Arkadiev, Boris, 81 chants directed against, 199, 225, 234, Assmy, Horst, 131 332 Aston Villa, 120 creation and early years, 226 athletics, 5, 51, 134 cup final vs. Dynamo Dresden (1985), Austria Vienna, 120, 178 204, 235–7 Austrian football, 17 during the Wende, 315–16 in European competition, 101, 114, Bahr, Egon, 116 119–21 Ballack, Michael, 95, 328 media coverage of, 148, 227, 239–41 Baník Ostrava, 120, 214, 295 protests against the dominance -

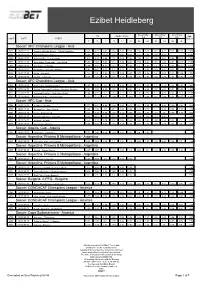

Ezibet Heidleberg

Ezibet Heidleberg Over/Under Over/Under Over/Under 1X2 Double chance 2.5 1.5 0.5 Add. CODE DATE EVENT Markets 1 X 2 1X 12 X2 Ov Un Ov Un Ov Un Soccer: AFC Champions League - Asia 9523 06-03 12:00 Jeonbuk Hyundai Motors - Tianjin Songjiang 1.56 4.21 5.43 1.14 1.21 2.36 1.56 2.32 1.16 4.72 1.01 12.61 +108 0240 06-03 12:30 Kashiwa Reysol - Kitchee 1.06 12.61 25.37 1.01 1.01 8.22 1.21 3.99 1.05 8.23 +116 3369 06-03 13:00 Buriram PEA - Cerezo Osaka 3.5 3.43 2.05 1.73 1.29 1.28 1.93 1.8 1.25 3.61 1.02 10.19 +105 5037 06-03 14:00 Guangzhou Evergrande - Jeju United 1.59 4.04 5.25 1.14 1.22 2.29 1.59 2.24 1.16 4.65 1.01 12.14 +110 1953 06-03 14:30 Zob-Ahan - Al Wahda 1.84 3.62 4.07 1.22 1.27 1.92 1.7 2.07 1.2 4.18 1.01 11.57 +103 6576 06-03 17:00 Al Duhail - Lokomotiv Tashkent 1.47 4.41 6.31 1.1 1.19 2.6 1.51 2.43 1.15 4.97 1.01 13.27 +110 4322 06-03 17:20 Al Ain - Esteghlal 1.6 3.9 5.44 1.13 1.24 2.27 1.73 2.02 1.2 4.08 1.01 11.24 +106 9213 06-03 19:15 Al Hilal - Al Rayyan 1.45 4.73 6.09 1.11 1.17 2.66 1.36 2.95 1.09 6.33 1.01 15.82 +112 Soccer: AFC Champions League - Asia 6522 07-03 10:30 Sydney FC - Kashima Antlers 2.67 3.45 2.5 1.5 1.29 1.45 1.71 2.05 1.2 4.19 1.01 11.34 +108 2599 07-03 12:00 Suwon Samsung Bluewings - Shanghai Shenhua 1.63 3.98 4.99 1.16 1.23 2.21 1.6 2.22 1.17 4.58 1.01 12.05 +110 4122 07-03 12:00 Kawasaki Frontale - Melbourne Victory 1.44 4.81 6.2 1.11 1.17 2.7 1.37 2.92 1.1 6.02 1.01 15.1 +113 7715 07-03 14:00 Shanghai SIPG - Ulsan Hyundai 1.39 5.13 6.67 1.09 1.15 2.89 1.37 2.88 1.11 5.88 1.01 14.77 +110 Soccer: AFC Cup -

Mr. Dorian Deaconescu, Hcc 6 8, Bãile Govora, Vâlcea

Mr. Dorian Deaconescu, Hcc 6 8, Bãile Govora, Vâlcea, 245200, Romania Statement of Account www.bet365.com Username - vodafonesmart3 (Account Number BT83908541) Statement Period - From 01/01/2015 to 15/10/2015 Transaction Summary Amount (RON) Code Stakes of bets placed 31863.29 D Returns on settled bets 26347.15 E Please note the summary above does not include any transaction funded by bet365 bonuses Bets placed in this period Tran. Date/Time Event Selection && Odds Result Stake Returns Code 01/01/2015 04:30:31 Southampton v Arsenal (Full Time Arsenal 2.62 Lost Result) Liverpool v Leicester (Full Time Result) Liverpool 1.40 Lost LA Kings @ VAN Canucks (Total 2-Way) Sub 5.5 1.57 Won Stoke v Man Utd (Double Chance) Egal sau Man Utd 1.22 Won Tottenham v Chelsea (Double Chance) Egal sau Chelsea 1.18 Lost Barnet v Aldershot (Additional Total Peste 1.20 Lost Goals) Six-Folds 1 x 2.50 2.50 0.00 D 01/01/2015 04:34:11 Southampton v Arsenal (Full Time Southampton 2.87 Won Result) Liverpool v Leicester (Full Time Result) Liverpool 1.40 Lost LA Kings @ VAN Canucks (Total 2-Way) Sub 5.5 1.57 Won Stoke v Man Utd (Double Chance) Egal sau Man Utd 1.22 Won Tottenham v Chelsea (Double Chance) Egal sau Chelsea 1.18 Lost Barnet v Aldershot (Additional Total Peste 1.20 Lost Goals) Six-Folds 1 x 2.50 2.50 0.00 D 01/01/2015 12:40:16 Stoke v Man Utd (Full Time Result) Man Utd 1.90 Lost Liverpool v Leicester (Full Time Result) Liverpool 1.44 Lost Mubadala World Tennis Championship Stanislas Wawrinka 1.22 Won - Stanislas Wawrinka vs Nicolas Almagro (To Win Match) -

Bundesliga 2 Season Schedule 2015/2016

SEASON SCHEDULE 2015/2016 BUNDESLIGA 2 Date Kick-off MD Match Home Away 24.07.2015 20.30 1 9 MSV Duisburg 1. FC Kaiserslautern 25.-27.07.2015 1 1 Sport-Club Freiburg 1. FC Nürnberg 25.-27.07.2015 1 2 SC Paderborn 07 VfL Bochum 1848 25.-27.07.2015 1 3 Eintracht Braunschweig SV Sandhausen 25.-27.07.2015 1 4 1. FC Union Berlin Fortuna Düsseldorf 25.-27.07.2015 1 5 SpVgg Greuther Fuerth Karlsruher SC 25.-27.07.2015 1 6 FC St. Pauli Hamburg DSC Arminia Bielefeld 25.-27.07.2015 1 7 1. FC Heidenheim 1846 TSV 1860 Munich 25.-27.07.2015 1 8 FSV Frankfurt 1899 RB Leipzig 28./29.07.2015 UCL Q3 A 30.07.2015 UEL Q3 A 01.08.2015 20.30 DFL SCUP VfL Wolfsburg FC Bayern München 31.07.-03.08.2015 2 10 Karlsruher SC FC St. Pauli Hamburg 31.07.-03.08.2015 2 11 1. FC Kaiserslautern Eintracht Braunschweig 31.07.-03.08.2015 2 12 RB Leipzig SpVgg Greuther Fuerth 31.07.-03.08.2015 2 13 1. FC Nürnberg 1. FC Heidenheim 1846 31.07.-03.08.2015 2 14 Fortuna Düsseldorf SC Paderborn 07 31.07.-03.08.2015 2 15 VfL Bochum 1848 MSV Duisburg 31.07.-03.08.2015 2 16 TSV 1860 Munich Sport-Club Freiburg 31.07.-03.08.2015 2 17 SV Sandhausen 1. FC Union Berlin 31.07.-03.08.2015 2 18 DSC Arminia Bielefeld FSV Frankfurt 1899 04./05.08.2015 UCL Q3 B 06.08.2015 UEL Q3 B 07.-10.08.2015 DFB R1 11.08.2015 20.45 USUP in Tbilisi (GEO) © DIE LIGA – Fußballverband e.V. -

Allianz Arena Football Stadium

Serial Iconic Buildings Allianz Arena Football Stadium Vojtěch Petrík In 2001, a referendum was held in which the citizens of Munich [email protected] determined that a new football stadium should be built on the outskirts of the city in the Fröttmaning district. The foundation Allianz Arena is a football stadium in Munich stone was laid down on 21 October 2002 and construction which serves as a home stadium for two football work was already completed in April 2005. The arena was offici- clubs: FC Bayern Munich and TSV 1860 Munich. It was officially ally opened on 30 May 2005 when TSV 1860 Munich played an opened in 2005 and a year later, it already hosted selected exhibition match against 1. FC Nürnberg. matches of the World Cup and the Champions League. In terms of capacity, Allianz Arena is the second largest stadium in Ger- Only two projects out of eight advanced to the final phase of many. The stadium’s unique technical and architectonic nature the tender procedure. The winning project was created by the made it one of the city’s most distinguished buildings immedia- Swiss architect firm Herzog & de Meuron which also designed tely after its opening. another iconic building of modern Germany, the Elbe Philhar- monic Hall. The Swiss architects developed the concept of the 2 Serial stadium made of 2,748 transparent trapezoid ETFE-foil panels to EUR 340 million. Due to financial turbulences, TSV München that can be lit from the inside with various colours. The archi- von 1860 GmbH & CO. KGaA had to sell its share to FC Bayern tects primarily aimed to create a modern building working with München AG which has been the sole owner since then. -

Live Live Live

LIVE LIVE LIVE 21.10. 09:00 Tokyo Verdy Tochigi SC 21.10. 10:00 Guangzhou R&f Dalian Aerbing 21.10. 11:00 TSV Alemannia Fortuna 21.10. 11:00 Spvgg SC Freiburg 21.10. 11:00 TSV 1860 Munich FC Augsburg 21.10. 11:00 Borussia Rot Weiss Essen 21.10. 11:00 FC Amkar Perm RFK Terek 21.10. 11:00 Arminia Bielefeld Borussia 21.10. 12:00 CD Guijuelo Tenerife CD 21.10. 12:00 Racing Santander CD Lugo 21.10. 12:00 Real Madrid C FC Coruxo 21.10. 12:00 Metallurg Salavat Yulaev 21.10. 12:00 Getafe Levante C + Liga 21.10. 12:00 Sibir Novosibirsk AK Bars Kazan 21.10. 12:15 Valencia Blusens Monbus Arena Sport 1 21.10. 12:30 Cagliari Bologna Sky Calcio 21.10. 12:30 ADO Den Haag Utrecht Eredivisie 21.10. 13:00 FC Vestsjaelland Vejle Boldklub 21.10. 13:00 FC Fredericia HB Koge 21.10. 13:00 Vorskla Poltava FC Metalurg 21.10. 13:00 TKI Tavsanli Karsiyaka 21.10. 13:15 CSKA Moscow Rubin Kazan Al Jazeera +9 21.10. 13:30 FC Union Berlin FSV Frankfurt 21.10. 13:30 Hertha BSC Berlin Torgelower Greif 1 of 8 21.10. 13:30 SC Paderborn FC St. Pauli 21.10. 13:30 VfR Aalen Energie Cottbus 21.10. 13:45 Heart of Motherwell FC 21.10. 13:45 Woodlands Brunei Dpmm FC 21.10. 14:00 Chemnitzer FC 1 FC Saarbrucken 21.10. 14:00 Baerum SK Kongsvinger IL 21.10. 14:00 AC Ajaccio SC Bastia 21.10.