Five Years and Was Completely Renovated by Crosby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A CYCLE MAP ROUTE 2 START Rail Line C207 A27 CHARLESTON.ORG.UK Wick St Firle the Street A27 Lewes Road C39

H H H H H H H H HH H PUBLIC TRANSPORT H H H Regular train services from H H H H H London Victoria to Lewes, H H Lewes H H about 7 miles from Charleston. H H H H H The nearest train stations are H H Stanmer A277 H H H H H HH Berwick and Glynde, both H Park H H BrightonH Rd H about 4 miles from Charleston. H H H Falmer H H H A27 H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H Glynde H A27 H H H ROUTE 2 H H H H H START HH A27 H A270 H Moulsecoomb H HH H H Wild Park H A27 H H H H H H H H A26 H H H H H H H H H H H H H ROUTE ONE H H H Lewes Road H H H H H HHHHHHHHH B2123 C7 H H H H H 16.5 miles/26.6km H H Brighton to Charleston H H H H H Brighton ROUTE 1 Glynde START Station A CYCLE MAP ROUTE 2 START rail line C207 A27 CHARLESTON.ORG.UK Wick St Firle The Street A27 Lewes Road C39 Selmeston Berwick ROUTE 3 Station START Old Coach Rd Common Lane Supported by ROUTE TWO ROUTE THREE A27 3.2 miles/5.1km 3.3 miles/5.3km Bo Peep Lane C39 Alciston Glynde to Charleston Berwick to Charleston join you on the left. -

Feminist and Queer Formations in Digital Networks

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Remediating politics: feminist and queer formations in digital networks Aristea Fotopoulou University of Sussex Thesis submitted September 2011 in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Acknowledgements Particular thanks go to my supervisors Caroline Bassett and Kate O'Riordan for their unreserved encouragement, support and feedback. I am grateful to Olu Jenzen, Beth Mills, Russell Pearce, Polly Ruiz, Rachel Wood and Lefteris Zenerian for commenting on drafts and to Ruth Charnock and Dan Keith for proof-reading. I'd also like to thank my colleagues in the School of Media, Film and Music and especially Sarah Maddox for being so understanding; my fellows in English, Global Studies, Institute of Development Studies, and Sociology at Sussex for their companionship. I am grateful for discussions that took place in the intellectual environments of the Brighton and Sussex Sexualities Network (BSSN), the Digital Communication and Culture Section of the European Communication Research and Education Association (ECREA), the ECREA Doctoral Summer School 2009 in Estonia, the 2011 Feminist Technoscience Summer School in Lancaster University, the Feminist and Women's Studies Association (FWSA), the 18th Lesbian Lives Conference, the Ngender Doctoral seminars 2009-2011 at the University of Sussex, the Research Centre for Material Digital Culture, and the Sussex Centre for Cultural Studies. -

BULLETIN Vol 50 No 1 January / February 2016

CINEMA THEATRE ASSOCIATION BULLETIN www.cta-uk.org Vol 50 No 1 January / February 2016 The Regent / Gaumont / Odeon Bournemouth, visited by the CTA last October – see report p8 An audience watching Nosferatu at the Abbeydale Sheffield – see Newsreel p28 – photo courtesy Scott Hukins FROM YOUR EDITOR CINEMA THEATRE ASSOCIATION (founded 1967) You will have noticed that the Bulletin has reached volume 50. How- promoting serious interest in all aspects of cinema buildings —————————— ever, this doesn’t mean that the CTA is 50 years old. We were found- Company limited by guarantee. Reg. No. 04428776. ed in 1967 so our 50th birthday will be next year. Special events are Registered address: 59 Harrowdene Gardens, Teddington, TW11 0DJ. planned to mark the occasion – watch this space! Registered Charity No. 1100702. Directors are marked ‡ in list below. A jigsaw we bought recently from a charity shop was entitled Road —————————— PATRONS: Carol Gibbons Glenda Jackson CBE Meets Rail. It wasn’t until I got it home that I realised it had the As- Sir Gerald Kaufman PC MP Lucinda Lambton toria/Odeon Southend in the background. Davis Simpson tells me —————————— that the dome actually belonged to Luker’s Brewery; the Odeon be- ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP SUBSCRIPTIONS ing built on part of the brewery site. There are two domes, marking Full Membership (UK) ................................................................ £29 the corners of the site and they are there to this day. The cinema Full Membership (UK under 25s) .............................................. £15 Overseas (Europe Standard & World Economy) ........................ £37 entrance was flanked by shops and then the two towers. Those Overseas (World Standard) ........................................................ £49 flanking shops are also still there: the Odeon was demolished about Associate Membership (UK & Worldwide) ................................ -

Heritage-Statement

Document Information Cover Sheet ASITE DOCUMENT REFERENCE: WSP-EV-SW-RP-0088 DOCUMENT TITLE: Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’: Final version submitted for planning REVISION: F01 PUBLISHED BY: Jessamy Funnell – WSP on behalf of PMT PUBLISHED DATE: 03/10/2011 OUTLINE DESCRIPTION/COMMENTS ON CONTENT: Uploaded by WSP on behalf of PMT. Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’ ES Chapter: Final version, submitted to BHCC on 23rd September as part of the planning application. This document supersedes: PMT-EV-SW-RP-0001 Chapter 6 ES - Cultural Heritage WSP-EV-SW-RP-0073 ES Chapter 6: Cultural Heritage - Appendices Chapter 6 BSUH September 2011 6 Cultural Heritage 6.A INTRODUCTION 6.1 This chapter assesses the impact of the Proposed Development on heritage assets within the Site itself together with five Conservation Areas (CA) nearby to the Site. 6.2 The assessment presented in this chapter is based on the Proposed Development as described in Chapter 3 of this ES, and shown in Figures 3.10 to 3.17. 6.3 This chapter (and its associated figures and appendices) is not intended to be read as a standalone assessment and reference should be made to the Front End of this ES (Chapters 1 – 4), as well as Chapter 21 ‘Cumulative Effects’. 6.B LEGISLATION, POLICY AND GUIDANCE Legislative Framework 6.4 This section provides a summary of the main planning policies on which the assessment of the likely effects of the Proposed Development on cultural heritage has been made, paying particular attention to policies on design, conservation, landscape and the historic environment. -

Wild Park Rainscape Proposal Project Summary and Supporting Statements

Brighton ChaMP* for Water Protecting our precious groundwater in the South Downs Contact: Aimee Felus, ChaMP Project Manager E: [email protected] T: 01730 819282 M: 07887 415149 Wild Park Rainscape Proposal Project Summary and Supporting Statements Current drainage system for Strategic Road Network (SRN) in project location: Surface water drainage discharges from the A27 into a balancing pond at Woollards Way, Brighton BN1 9BP. Water and any associated contaminants then pass into a traditional piped system adjacent to Lewes Rd, prior to ultimately discharging to a series of soakaways in Wild Park, Lewes Rd, Moulsecoomb, Brighton, BN1 9JR. The site lies in a Source Protection Zone 1 and 2 (SPZ1 and 2) for drinking water. A recent PhD conducted at the University of Brighton has demonstrated presence of a range of potential contaminants in the balancing pond (heavy metals and hydrocarbons) with zinc and benzo (a) pyrene being of particular concern. Figure 1: Location of proposed projects - Woollards Way, Brighton, BN1 9BP (TQ 34107 08324), and Wild Park, Lewes Rd, Moulsecoomb, Brighton, BN1 9JR (TQ 33187 07875) *Chalk Management Partnership Balancing pond at Woollards Way Series of soakaways in Wild Park Figure 2: Location of balancing pond and soakaways and SPZ1 and 2 (shown in red and green respectively) Figure 3: Balancing pond at Woollards Way shows evidence of contamination with hydrocarbons and heavy metals Figure 4: Balancing pond with water Figure 5: Soakaway in Wild Park with contaminated silts and black water Summary of Proposed Project: Proposals are to modify the existing system and create a Sustainable Drainage System (SuDS), or ‘Rainscape’, that prevents pollution of groundwater. -

Brighton Clr Cdd with Bus Stops

C O to Horsham R.S.P.C.A. L D E A N L A . Northfield Crescent 77 to Devil’s Dyke 17 Old Boat 79‡ to Ditchling Beacon 23 -PASS HOVE BY Corner 270 to East Grinstead IGHTON & 78‡ BR Braeside STANMER PARK 271.272.273 to Crawley Glenfalls Church D Avenue 23.25 E L Thornhill Avenue East V O I N Avenue R L’ NUE Park Village S D AVE E F O 5A 5B# 25 N Sanyhils Crowhurst N E 23 E E C Brighton Area Brighton Area 5 U Crowhurst * EN D AV 24 T Avenue Road R D Craignair O Y DE A Road Bramber House I R K R ES West C 25 Avenue A Stanmer Y E O BR Eskbank North Hastings D A 5B#.23 Saunders Hill B * A D Avenue R 23 Building R O IG 17 University D 25.25X H R H R C T Village . Mackie Avenue A Bus Routes Bus Routes O 270 Patcham WHURST O O RO N A C Asda W L D Barrhill D B & Science Park Road 271 K E of Sussex 28 to Ringmer 5.5A 5B.26 North Avenue A Top of A H H R 5B.24.26 272 Hawkhurst N O South U V R 46 29.29X# 5A UE E 78‡ 25 H 5 AVEN Thornhill Avenue R Road Falmer Village 273 E * 52.55# Road L B I I K S A C PORTFIELD 52. #55 Y L A toTunbridge Wells M Bowling N - Sussex House T P L 5B# 5B# A Haig Avenue E S Green S 52 Carden W Cuckmere A S Sport Centre S P Ladies A A A V O 24 KEY P PortfieldV Hill Way #29X T R - . -

Enforcement Register 31.7.2019.Pdf

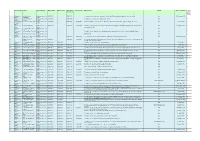

Type of notice Address Issuing authority Date of issue Date of service Date notice Date of expiry Requirements Appeal Date of compliance Check takes effect against local search 2 Enforcement 16a Nevill Road, Brighton & Hove City 10/05/1974 10/06/1974 The change of use of the south-east room in the first floor flat from single dwellinghouse to use as an office. N/A 10 September 1974 Notice Rottingdean, Council 3 Enforcement 9a Port Hall Street, Brighton & Hove City 22/05/1963 26/03/1990 Discontinue use of garage for repair of motor vehicles. N/A 5 Notice Brighton. Council 4 Listed Building 37 Lansdowne Place, Hove. Brighton & Hove City 25/02/1992 03/04/1992 03/10/1992 Replace Victorian fire surrounds from first floor front room, 2nd floor front room, replace ceiling plaster cornice . N/A 17 March 1993 3 Enforcement Council Notice 5 Enforcement 153 Nevill Road, Hove Brighton & Hove City 30/05/1973 02/07/1973 02/01/1974 Discontinue use of property for the purpose of the business of repairing, maintaining preparing for sale and buying and N/A 09 January 1989 5 Notice Council selling motor vehicles. 6 Enforcement 113-116 Southover Street, Brighton & Hove City N/A 3 Notice Brighton. Council 7 Enforcement 28 Eastern Place, Brighton. Brighton & Hove City Discontinue the use of premises for dismantling and breaking motor vehicles and the storage of dismantled parts. N/A 5 Notice Council 8 Enforcement 33 Wilbury Gardens, Hove. Brighton & Hove City ENF/33WILG N/A 3 Notice Council 9 Abatement 51 St. -

Etches Along the Coastline and Contains Almost 500,000 People

The Ebb and Flow of Resistance: Analysis of the Squatters' Movement and Squatted Social Centres in Brighton by E.T.C. Dee University of Madrid Sociological Research Online, 19 (4), 6 <http://www.socresonline.org.uk/19/4/6.html> DOI: 10.5153/sro.3502 Received: 10 Jul 2014 | Accepted: 10 Sep 2014 | Published: 30 Nov 2014 Abstract This article analyses a database of 55 squatted social centres in Brighton. By virtue of their public nature, these projects provide a lens through which to examine the local political squatters' movement, which was often underground, private and hidden (residential squatting in contrast is not profiled). Several relevant non-squatted spaces are also included since they were used as organisational hubs by squatters. The data was gathered from a mixture of participant observation, reference to archive materials, conversations with squatters past and present, academic sources and activist websites. The projects are assessed in turn by time period, duration, type of building occupied and location (by ward). Significant individual projects are described and two boom periods identified, namely the late 1990s and recent years. Reasons for the two peaks in activity are suggested and criticised. It is argued that social centres bloomed in the 1990s as part of the larger anti-globalisation movement and more recently as a tool of resistance against the criminalisation of squatting. Tentative conclusions are reached concerning the cycles, contexts and institutionalisation of the squatters' movement. It is suggested that the movement exists in ebbs and flows, influenced by factors both internal (such as the small, transitory nature of the milieu) and external (such as frequent evictions). -

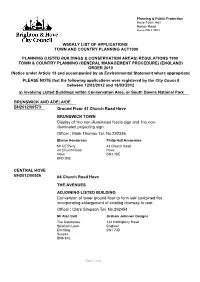

Cadenza Document

Planning & Public Protection Hove Town Hall Norton Road Hove BN3 3BQ WEEKLY LIST OF APPLICATIONS TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT1990 PLANNING (LISTED BUILDINGS & CONSERVATION AREAS) REGULATIONS 1990 TOWN & COUNTRY PLANNING (GENERAL MANAGEMENT PROCEDURE) (ENGLAND) ORDER 2010 (Notice under Article 13 and accompanied by an Environmental Statement where appropriate) PLEASE NOTE that the following applications were registered by the City Council between 12/03/2012 and 18/03/2012 a) Involving Listed Buildings within Conservation Area, or South Downs National Park BRUNSWICK AND ADELAIDE BH2012/00573 Ground Floor 43 Church Road Hove BRUNSWICK TOWN Display of 1no non-illuminated fascia sign and 1no non- illuminated projecting sign. Officer : Mark Thomas Tel. No.292336 Ellman Henderson Philip Hall Associates Mr CE Perry 43 Church Road 43 Church Road Hove Hove BN3 2BE BN3 2BE CENTRAL HOVE BH2012/00526 64 Church Road Hove THE AVENUES ADJOINING LISTED BUILDING Conversion of lower ground floor to form self-contained flat incorporating enlargement of existing doorway to rear. Officer : Clare Simpson Tel. No.292454 Mr Alan Bull Graham Johnson Designs The Gatehouse 134 Hollingbury Road Spatham Lane Brighton Ditchling BN1 7JD Sussex BN6 8XL Page 1 of 24 BH2012/00608 8 George Street Hove ADJOINING CLIFTONVILLE Display of non-illuminated fascia sign and projecting sign. Officer : Mark Thomas Tel. No.292336 Scope Futurama 6 Market Road Olympia House London Lockwood Court N7 9PW Midleton Grove Leeds West Yorkshire LS11 5TY BH2012/00675 53-54 George Street Hove ADJOINING CLIFTONVILLE Display of externally - illuminated fascia, projecting and ATM panel signs. Officer : Jason Hawkes Tel. No.292153 The Royal Bank of Scotland GroupInsignia Projects Limited Mr Peter Wilkinson G1 Marlowe Innovation Centre Property Services Marlowe Way First Floor East Ramsgate The Younger Building Kent 3 Redheugh Avenue CT12 6FA Edinburgh EH12 9RB EAST BRIGHTON BH2012/00607 32 College Gardens Brighton EAST CLIFF Replacement of wooden windows with upvc. -

Hove Civic Society October 2017 Newsletter and Asked for Volunteers to Look After the Trees

Hove Civic Society October 2017 Newsletter and asked for volunteers to look after the trees. We will Chairman’s Annual Report seek to sign up volunteers from the traders during the autumn to ensure that the trees received the TLC they Dear Members, deserve. This should help keep the trees healthy and safe. It is time to take stock of what has been a momentous We have also started discussions with the planning year. We have made huge progress on the Hove plinth department to explore how we can ensure that and first sculpture, come to an agreement on the next planting conditions for new developments are actually round of street tree planting, continued our involvement implemented. Bearing in mind the shortage of in the Hove Station Neighbourhood Forum and decided enforcement staff we believe that we need to find a way to leave the city wide Conservation Advisory Group. We where requirements for example for street tree planting have taken a fundamental look at how we can increase are not ignored. Cumulatively the costs to the community our work in the environmental field and have set out a for ignoring such conditions are substantial. programme that we intend to pursue. Our membership is steadily increasing, now at the highest level I can recall, Hove Plinth and first sculpture not least because of the numerous donations we have During the year the main effort has concentrated on received and consequently our finances are very healthy securing the final resources for the plinth and the first indeed. I would like to thank all our committee members sculpture. -

Wild Park Public Consultation Workshop Results – NWA – 12 January 2011 2

Wild Park Public Consultation Workshop Results Nick Wates Associates for Brighton & Hove City Council CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 2 Methodology 4 3 Response 5 4 Results – Likes summary 6 5 Results – Dislikes summary 7 6 Results – Action Plan - Now 9 7 Results – Action Plan - Soon 10 8 Results – Action Plan - Later 12 9 Results – Future engagement 13 10 Conclusions 14 Appendices A Transcripts – Likes 15 B Transcripts – Dislikes 18 C Transcripts – Action Plans 20 D Transcripts – Future engagement 28 E Transcripts – Letters and emails 30 F Transcripts – Workshop Evaluation 39 G Newsletter 42 H Flyer 48 J Workshop plan 49 K Powerpoint by Council Ecologist 52 L Photos of workshops 65 Wild Park Public Consultation Workshop Results – NWA – 12 January 2011 2 1 Introduction 1.1 Wild Park is a spectacular area of countryside on the outskirts of Brighton in the new South Downs National Park. It is managed by Brighton & Hove City Council. 1.2 During 2010 the first stage of a management plan to restore areas of chalk grassland was heavily criticised by some Brighton residents and direct action was taken to disrupt it. The Council therefore decided to re-consult with local residents on the best way forward. 1.3 Nick Wates Associates was commissioned as an independent facilitator to help plan and run a series of four workshops in the communities around the Park. 1.4 This report explains how the workshops were conducted and sets out the results. 1.5 For further information please contact: Wild Park Consultation Cityparks, Stanmer Nursery, Lewes Road, Brighton BN1 9SE Email: [email protected] Wild Park Public Consultation Workshop Results – NWA – 12 January 2011 3 2 Methodology 2.1 The workshops were planned by a Focus Group comprising councillors, officers and key residents. -

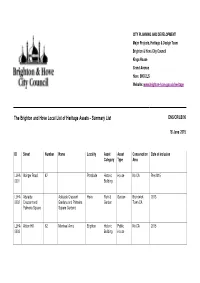

The Brighton and Hove Local List of Heritage Assets – Summary List ENS/CR/LB/06

CITY PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT Major Projects, Heritage & Design Team Brighton & Hove City Council Kings House Grand Avenue Hove BN3 2LS Website: www.brighton-hove.gov.uk/heritage The Brighton and Hove Local List of Heritage Assets – Summary List ENS/CR/LB/06 18 June 2015 ID Street Number Name Locality Asset Asset Conservation Date of inclusion Category Type Area LLHA Abinger Road 87 Portslade Historic House No CA Pre-2015 0001 Building LLHA Adelaide Adelaide Crescent Hove Park & Garden Brunswick 2015 0002 Crescent and Gardens and Palmeira Garden Town CA Palmeira Square Square Gardens LLHA Albion Hill 62 Montreal Arms Brighton Historic Public No CA 2015 0003 Building House LLHA Arcade Buildings 1-17 Imperial Arcade Brighton Historic Shop, No CA Pre-2015 0242 and 203-211 Building arcade Western Road LLHA Bath Street Petrol Pumps at 19A Brighton Historic Transport - West Hill CA 2015 0004 Building Petrol Pumps LLHA Bedford Place 3 Brighton Historic House Regency Pre-2015 0005 Building Square CA LLHA Boundary Road 29, 30 Hove Historic Houses, No CA Pre-2015 0006 Building now office, shop and dwelling LLHA Braybon Avenue Fountain Centre Brighton Historic Place of No CA 2015 0007 Building Worship - Anglican LLHA Bristol Gardens 12 The Estate of the First Brighton Historic Estate Within and 2015 0008 Marquis of Bristol: 12 Building buildings outside Kemp Bristol Gardens; 1-11 and walls Town CA (odd) Church Place; Walls to Badger's Tennis Courts; Walls to former Bristol Nurseries LLHA Brunswick Square Brunswick Square Hove Park & Garden Brunswick