The Cinematography of Roger Deakins: How His Visual Storytelling Reflects His Philosophies Abstract I. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toland Asc Digital Assistant

TOLAND ASC DIGITAL ASSISTANT PAINTING WITH LIGHT or more than 70 years, the American Cinematographer Manual has been the key technical resource for cinematographers around the world. Chemical Wed- ding is proud to be partners with the American Society of Cinematographers in bringing you Toland ASC Digital Assistant for the iPhone or iPod Touch. FCinematography is a strange and wonderful craft that combines cutting-edge technology, skill and the management of both time and personnel. Its practitioners “paint” with light whilst juggling some pretty challenging logistics. We think it fitting to dedicate this application to Gregg Toland, ASC, whose work on such classic films as Citizen Kane revolutionized the craft of cinematography. While not every aspect of the ASC Manual is included in Toland, it is designed to give solutions to most of cinematography’s technical challenges. This application is not meant to replace the ASC Manual, but rather serve as a companion to it. We strongly encourage you to refer to the manual for a rich and complete understanding of cin- ematography techniques. The formulae that are the backbone of this application can be found within the ASC Manual. The camera and lens data have largely been taken from manufacturers’ speci- fications and field-tested where possible. While every effort has been made to perfect this application, Chemical Wedding and the ASC offer Toland on an “as is” basis; we cannot guarantee that Toland will be infallible. That said, Toland has been rigorously tested by some extremely exacting individuals and we are confident of its accuracy. Since many issues related to cinematography are highly subjective, especially with re- gard to Depth of Field and HMI “flicker” speeds, the results Toland provides are based upon idealized scenarios. -

Viewing Film from a Communication Perspective

Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal Volume 36 Article 6 January 2009 Viewing Film from a Communication Perspective: Film as Public Relations, Product Placement, and Rhetorical Advocacy in the College Classroom Robin Patric Clair Purdue University, [email protected] Rebekah L. Fox Purdue University Jennifer L. Bezek Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/ctamj Part of the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Clair, R., Fox, R., & Bezek, J. (2009). Viewing Film from a Communication Perspective: Film as Public Relations, Product Placement, and Rhetorical Advocacy in the College Classroom. Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal, 36, 70-87. This Teacher's Workbook is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Clair et al.: Viewing Film from a Communication Perspective: Film as Public Rel 70 CTAMJ Summer 2009 Viewing Film from a Communication Perspective: Film as Public Relations, Product Placement, and Rhetorical Advocacy in the College Classroom Robin Patric Clair Professor [email protected] Rebekah L. Fox, Ph.D. Jennifer L. Bezek, M.A. Department of Communication Purdue University West Lafayette, IN ABSTRACT Academics approach film from multiple perspectives, including critical, literary, rhetorical, and managerial approaches. Furthermore, and outside of film studies courses, films are frequently used as a pedagogical tool. -

Dance Design & Production Drama Filmmaking Music

Dance Design & Production Drama Filmmaking Music Powering Creativity Filmmaking CONCENTRATIONS Bachelor of Master of Fine Arts Fine Arts The School of Filmmaking is top ranked in the nation. Animation Cinematography Creative Producing Directing Film Music Composition Picture Editing & Sound Design No.6 of Top 50 Film Schools by TheWrap Producing BECOME A SKILLED STORYTELLER Production Design & Visual Effects Undergraduates take courses in every aspect of the moving image arts, from movies, series and documentaries to augmented and virtual reality. Screenwriting You’ll immediately work on sets and experience firsthand the full arc of film production, including marketing and distribution. You’ll understand the many different creative leadership roles that contribute to the process and discover your strengths and interests. After learning the fundamentals, you’ll work with faculty and focus on a concentration — animation, cinematography, directing, picture editing No.10 of Top 25 American and sound design, producing, production design and visual effects, or Film Schools by The screenwriting. Then you’ll pursue an advanced curriculum focused on your Hollywood Reporter craft’s intricacies as you hone your leadership skills and collaborate with artists in the other concentrations to earn your degree. No.16 of Top 25 Schools for Composing for Film and TV by The Hollywood Reporter Filmmaking Ranked among the best film schools in the country, the School of Filmmaking produces GRADUATE PROGRAM experienced storytellers skilled in all aspects of the cinematic arts and new media. Students Top 50 Best Film Schools direct and shoot numerous projects alongside hands-on courses in every aspect of modern film Graduate students earn their M.F.A. -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

Success in the Film Industry

1 Abstract This paper attempted to answer the research question, “What determines a film’s success at the domestic box office?” The authors used an OLS regression model on data set of 497 films from the randomly selected years 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, and 2011, taking the top 100 films from each year. Domestic box-office receipts served as the dependent variable, with MPAA ratings, critical reviews, source material, release date, and number of screens acting as independent variables in the final regression. Results showed that source material, critical reviews, number of screens, release date, and some genres were statistically significant and positively contributed to a film’s domestic revenue. Introduction Each year in the United States, hundreds of films are released to domestic audiences in the hope that they will become the next “blockbuster.” The modern film industry, a business of nearly 10 billion dollars per year, is a cutthroat business (Box Office Mojo). According to industry statistics, six or seven of every ten films are unprofitable, making the business risky at best (Brewer, 2006). Given this inherent risk, how do film studios decide which films to place their bets on? Are there common factors, such as critical reviews, MPAA rating, or production budget, which explain one film’s monetary success relative to another? This question forms the basis of this research project. To answer it, we estimated an Ordinary Least Squares regression that attempted to explain the monetary success of the top films in five years out of the past decade. This regression expanded our original dataset, which used 100 randomly selected films from 2004. -

Filmmaking High School 1AB High School

Filmmaking High School 1AB High School Course Title Filmmaking High School 1A/B Course Abbreviation FILMMAKING 1 A/B Course Code Number 200511/200512 Special Notes Course Description The purpose of this course is to provide a balanced visual arts program, which guides students to achieve the standards in the visual arts. In Filmmaking, students experience both the creative and technical aspects of filmmaking in conjunction with learning about historical and contemporary traditions. Story writing, story-based display, basic visual composition, and general reproduction skills will be included with camera techniques, animation, and line action planning. Traditional filmmaking traditions may be extended with video and multimedia technologies. Interdisciplinary experiences and arts activities lead to refining a personal aesthetic, and a heightened understanding of career opportunities in art and arts-related fields. Instructional Topics Historical Foundations of Cinema Aesthetic Decisions and Personal Judgment Introduction to Filmmaking and Multimedia Preproduction Planning Establishing a Theme Storyboarding and Scriptwriting Set, Prop and Costume Design Camera Techniques Design Elements in Cinema Sound, Lighting, Editing Live Action Filming Animation Techniques Documentation and Portfolio Preparation Careers in Cinema and Multimedia *Topics should be presented in an integrated manner where possible; time spent on each topic is to be based upon the needs of the student, the instructional program, and the scheduling needs of the school. California Visual Arts Content knowledge and skills gained during this course will support student achievement of Content Standards grade level Student Learning Standards in the Visual Arts. High School Proficient Upon graduation from the LAUSD, students will be able to: 1. Process, analyze, and respond to sensory information through the language and skills unique to the visual arts. -

BLADE RUNNER 2049 “I Can Only Make So Many.” – Niander Wallace REPLICANT SPRING ROLLS

BLADE RUNNER 2049 “I can only make so many.” – Niander Wallace REPLICANT SPRING ROLLS INGREDIENTS • 1/2 lb. shrimp Dipping Sauce: • 1/2 lb. pork tenderloin • 2 tbsp. oil • Green leaf lettuce • 2 tbsp. minced garlic • Mint & cilantro leaves • 8 tbsp. hoisin sauce • Chives • 2-3 tbsp. smooth peanut butter • Carrot cut into very thin batons • 1 cup water • Rice paper — banh trang • Sriracha • Rice vermicelli — the starchless variety • Peanuts • 1 tsp salt • 1 tsp sugar TECHNICOLOR | MPC FILM INSTRUCTIONS • Cook pork in water, salt and sugar until no longer pink in center. Remove from water and allow to cool completely. • Clean and cook shrimp in boiling salt water. Remove shells and any remaining veins. Split in half along body and slice pork very thinly. Boil water for noodles. • Cook noodles for 8 mins plunge into cold water to stop the cooking. Drain and set aside. • Wash vegetables and spin dry. • Put warm water in a plate and dip rice paper. Approx. 5-10 seconds. Removed slightly before desired softness so you can handle it. Layer ingredients starting with lettuce and mint leaves and ending with shrimp and carrot batons. Tuck sides in and roll tightly. Dipping Sauce: • Cook minced garlic until fragrant. Add remaining ingredients and bring to boil. Remove from heat and garnish with chopped peanuts and cilantro. BLADE RUNNER 2049 “Things were simpler then.” – Agent K DECKARD’S FAVORITE SPICY THAI NOODLES INGREDIENTS • 1 lb. rice noodles • 1/2 cup low sodium soy sauce • 2 tbsp. olive oil • 1 tsp sriracha (or to taste) • 2 eggs lightly beaten • 2 inches fresh ginger grated • 1/2 tbsp. -

List of Sunlight Media Collective Members & Board Sunlight Media

List of Sunlight Media Collective Members & Board Sunlight Media Collective Core Leadership Bios • Dawn Neptune Adams (Penobscot Tribal Member, Racial Justice Consultant to the Peace + Justice Center of Eastern Maine, Wabanaki liaison to Maine Green Independent Party Steering Committee + environmental & Indigenous rights activist). Dawn is a Sunlight Media Collective content advisor, journalist, public speaker, narrator, production assistant, grant writer + event organizer. • Maria Girouard (Penobscot Tribal Member, Historian focused on Maine Indian Land Claims Settlement Act, Coordinator of Wabanaki Health + Wellness at Maine- Wabanaki REACH + environmental & Indigenous rights activist). Maria is a Sunlight Media Collective co-founder, film director, writer, content advisor, public speaker + event organizer. • Meredith DeFrancesco (Radio Journalist of RadioActive on WERU, environmental & Indigenous rights activist). Meredith is a Sunlight Media Collective co- founder, film producer, film director, journalist, organizational & financial management person + event organizer. • Sherri Mitchell (Penobscot Tribal Member, lawyer, environmental & Indigenous rights activist, author, and Director of Land Peace Foundation). Sherri is a Sunlight Media Collective content advisor, writer, grant writer, public speaker + event organizer. • Josh Woodbury (Penobscot Tribal Member, Tribal IT Department and Cultural & Historic Preservation Department, + Filmmaker). Josh is a Sunlight Media Collective cinematographer, film editor, web designer + content -

The General Idea Behind Editing in Narrative Film Is the Coordination of One Shot with Another in Order to Create a Coherent, Artistically Pleasing, Meaningful Whole

Chapter 4: Editing Film 125: The Textbook © Lynne Lerych The general idea behind editing in narrative film is the coordination of one shot with another in order to create a coherent, artistically pleasing, meaningful whole. The system of editing employed in narrative film is called continuity editing – its purpose is to create and provide efficient, functional transitions. Sounds simple enough, right?1 Yeah, no. It’s not really that simple. These three desired qualities of narrative film editing – coherence, artistry, and meaning – are not easy to achieve, especially when you consider what the film editor begins with. The typical shooting phase of a typical two-hour narrative feature film lasts about eight weeks. During that time, the cinematography team may record anywhere from 20 or 30 hours of film on the relatively low end – up to the 240 hours of film that James Cameron and his cinematographer, Russell Carpenter, shot for Titanic – which eventually weighed in at 3 hours and 14 minutes by the time it reached theatres. Most filmmakers will shoot somewhere in between these extremes. No matter how you look at it, though, the editor knows from the outset that in all likelihood less than ten percent of the film shot will make its way into the final product. As if the sheer weight of the available footage weren’t enough, there is the reality that most scenes in feature films are shot out of sequence – in other words, they are typically shot in neither the chronological order of the story nor the temporal order of the film. -

A TRIBUTE to OSWALD MORRIS OBE, DFC, AFC, BSC Introduced by Special Guests Duncan Kenworthy OBE, Chrissie Morris and Roger Deakins CBE, ASC, BSC

BAFTA HERITAGE SCREENING Monday 23 June 2O14, BAFTA, 195 Piccadilly, London W1J 9LN THE HILL: A TRIBUTE TO OSWALD MORRIS OBE, DFC, AFC, BSC Introduced by special guests Duncan Kenworthy OBE, Chrissie Morris and Roger Deakins CBE, ASC, BSC SEAN CONNERY AND HARRY ANDREW IN THE HILL THE (1965) Release yeaR: 1965 Transport Command, where as a Flight Lt. he flew Sir Anthony Runtime: 123 mins Eden to Yalta, Clement Attlee to Potsdam, and the chief of the DiRectoR: Sidney Lumet imperial general staff, Lord Alanbrooke, on a world tour. cinematogRaphy: Oswald Morris After demobilization, Ossie joined Independent Producers at With special thanks to Warner Bros and the BFI Pinewood Studios in January 1946 and was engaged as camera operator on three notable productions; Green For Danger, Launder and Gilliat’s comedy-thriller concerning a series of orn in November 1915 Oswald Morris was a murders at a wartime emergency hospital; Captain Boycott, a 1947 dedicated film fan in his teenage years, working as historical drama, again produced by Launder and Gilliat and a cinema projectionist in his school holidays, before Oliver Twist, David Lean’s stunning adaptation of the classic novel entering the industry in 1932 as a runner and clapper by Charles Dickens photographed by Guy Green. Bboy at Wembley Studios, a month short of his 17th birthday. In 1949, Ossie gained his first screen credit as Director of The studio churned out quota quickies making a movie a week Photography on Golden Salamander, starring Trevor Howard as at a cost of one pound per foot of film. -

David Nellist

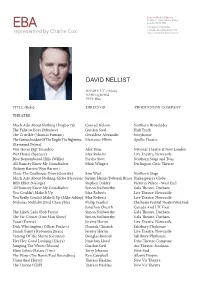

Eamonn Bedford Agency 1st Floor - 28 Mortimer Street London W1W 7RD EBA t +44(0) 20 7734 9632 e [email protected] represented by Charlie Cox www.eamonnbedford.agency DAVID NELLIST HEIGHT: 5’5” (165cm) HAIR: Light/Mid EYES: Blue TITLE (Role) DIRECTOR PRODUCTION COMPANY THEATRE Much Ado About Nothing (Dogberry) Conrad Nelson Northern Broadsides The Fulstow Boys (Maurice) Gordon Steel Hull Truck The Crucible (Thomas Putnam) Geraldine Alexander Storyhouse The Curious Incident Of The Dog In The Nighttime Marianne Elliott Apollo Theatre (Reverend Peters) War Horse (Sgt Thunder) Alex Sims National Theatre at New London Wet House (Spencer) Max Roberts Live Theatre, Newcastle Blue Remembered Hills (Willie) Psyche Stott Northern Stage and Tour Alf Ramsey Knew My Grandfather Mark Wingett Darlington Civic Theatre (Sidney Barron/Wyn Barron) Close The Coalhouse Door (Geordie) Sam West Northern Stage Much Ado About Nothing/Globe Mysteries Jeremy Herrin/Deborah Bruce Shakespeare’s Globe Billy Elliot (George) Stephen Daldry Victoria Palace - West End Alf Ramsey Knew My Grandfather Simon Stallworthy Gala Theatre, Durham You Couldn’t Make It Up Max Roberts Live Theatre, Newcastle You Really Coudn’t Make It Up (Mike Ashley) Max Roberts Live Theatre, Newcastle Nicholas Nickleby (Ned Cheeryble) Philip Franks/ Chichester Festival Theatre/West End Jonathan Church Canada And UK Tour The Likely Lads (Bob Ferris) Simon Stallworthy Gala Theatre, Durham The Far Corner (One Man Show) Simon Stallworthy Gala Theatre, Durham Toast (Dezzie) Jeremy Herrin Live Theatre, -

David Stratton's Stories of Australian Cinema

David Stratton’s Stories of Australian Cinema With thanks to the extraordinary filmmakers and actors who make these films possible. Presenter DAVID STRATTON Writer & Director SALLY AITKEN Producers JO-ANNE McGOWAN JENNIFER PEEDOM Executive Producer MANDY CHANG Director of Photography KEVIN SCOTT Editors ADRIAN ROSTIROLLA MARK MIDDIS KARIN STEININGER HILARY BALMOND Sound Design LIAM EGAN Composer CAITLIN YEO Line Producer JODI MADDOCKS Head of Arts MANDY CHANG Series Producer CLAUDE GONZALES Development Research & Writing ALEX BARRY Legals STEPHEN BOYLE SOPHIE GODDARD SC SALLY McCAUSLAND Production Manager JODIE PASSMORE Production Co-ordinator KATIE AMOS Researchers RACHEL ROBINSON CAMERON MANION Interview & Post Transcripts JESSICA IMMER Sound Recordists DAN MIAU LEO SULLIVAN DANE CODY NICK BATTERHAM Additional Photography JUDD OVERTON JUSTINE KERRIGAN STEPHEN STANDEN ASHLEIGH CARTER ROBB SHAW-VELZEN Drone Operators NICK ROBINSON JONATHAN HARDING Camera Assistants GERARD MAHER ROB TENCH MARK COLLINS DREW ENGLISH JOSHUA DANG SIMON WILLIAMS NICHOLAS EVERETT ANTHONY RILOCAPRO LUKE WHITMORE Hair & Makeup FERN MADDEN DIANE DUSTING NATALIE VINCETICH BELINDA MOORE Post Producers ALEX BARRY LISA MATTHEWS Assistant Editors WAYNE C BLAIR ANNIE ZHANG Archive Consultant MIRIAM KENTER Graphics Designer THE KINGDOM OF LUDD Production Accountant LEAH HALL Stills Photographers PETER ADAMS JAMIE BILLING MARIA BOYADGIS RAYMOND MAHER MARK ROGERS PETER TARASUIK Post Production Facility DEFINITION FILMS SYDNEY Head of Post Production DAVID GROSS Online Editor