Effect of Row Spacing and Seeding Rate on Russian Thistle (Salsola Tragus) in Spring Barley and Spring Wheat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turfgrass Selection Ryegrasses

Extension W159-F Turfgrass Selection Ryegrasses Tom Samples, Professor and John Sorochan, Associate Professor Plant Sciences Due to rapid seed germination and seedling growth, ryegrasses were once planted as nurse Varieties grasses in seed ‘Florida 80’ (1982, Florida AES), ‘Gulf’ (1958, mixtures with Texas AES and Plant Research Division ARS), slower-growing, ‘Jackson’ (1989, Mississippi AFES), ‘Marshall’ perennial cool- (1980, Mississippi AFES) and ‘TAM 90’ (1991, season species Texas AES) continue to be used to temporarily including the control soil erosion in the South. ‘Axcella,’ fescues and evaluated as ABT-99-3-268 and recently (2001) Kentucky released by the Texas AES, Overton, Texas, is the bluegrass. first turf-type variety marketed for winter over- Unfortunately, seeding of bermudagrass turfs. This variety is an ryegrasses early-maturing, dwarf-type and is darker than can be very other annual ryegrasses. Axcella has finer leaves, aggressive in greater stand density and a slower vertical growth mixed stands, and may dominate a preferred rate than many other annual ryegrasses. Seeds turfgrass species by competing for nutrients, of Axcella annual ryegrass are about 25 percent sunlight, water and space. Intermediate (Lolium larger than perennial ryegrass seeds. When over- hybridum) and perennial (Lolium perenne L.) seeded alone or with varieties of intermediate ryegrasses are sometimes used to over-seed and perennial ryegrasses, Axcella matures quickly dormant bermudagrass. Annual ryegrass (Lolium and transitions from the stand as bermudagrass multiflorum Lam.) is widely used to provide resumes growth in spring. temporary ground cover and soil erosion control until a perennial turf can be planted. Intermediate Ryegrass Annual Ryegrass Intermediate or transitional ryegrass is a hybrid Annual ryegrass, also known as Italian ryegrass, of annual and perennial ryegrass. -

Some Observations on Salsola L. (Chenopodiaceae) in Australia R.J

© 2010 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium, Government of South Australia J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. 24 (2010) 75–79 © 2010 Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia NOTE Some observations on Salsola L. (Chenopodiaceae) in Australia R.J. Chinnock State Herbarium of South Australia, P.O. Box 2732, Kent Town, South Australia 5071 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In recent years there has been much confusion as to the correct name application for the Australian species of Salsola L. Prior to the late 1990’s S. kali L. was universally applied throughout Australia but Rilke (1999) adopted the name S. tragus L. and more recently some authors have taken up the name S. australis R.Br. Molecular studies by Hrusa & Gaskin (2008), Borger et al. (2008) and Ayers et.al. (2008) confirm that Salsola australis is distinct from both S. tragus and S. kali so this name has been adopted for the forthcoming 5th edition of the Flora of South Australia. Observation of Salsola populations in Western Australia and South Australia suggest that Salsola australis is a complex of at least six forms which require an Australian-wide molecular/ systematic study to determine their status. Keywords: Chenopodiaceae, Salsola, S. australis, S. austroafricanus, S. tragus, S. kali, molecular studies, observations of populations in Western Australia and South Australia Introduction haplotypes mostly exclusive to the tetraploid S. tragus When preparing the genera of Chenopodiaceae for and the diploid Salsola ‘type B’. Salsola ‘type C’ was the fifth edition of the Flora of South Australia (in prep.) determined to be a fertile allohexaploid resulting from a problem arose over the application of the species name hybridisation between S. -

RYEGRASSES the 17Th in a Series by R.W

UNDERSTANDING TURF MANAGEMENT RYEGRASSES the 17th in a series by R.W. Sheard, P. Ag. yegrass originally developed as a grass is more difficult to mow than other are formed. The stems will resist mowing Rpasture grass which would withstand turfgrass species. A whitish appearance, by reel mowers giving the sports field a close grazing and had a superior ability to due to shredded, mutilated leaves, may be ragged appearance. produce meat and milk. Even today nitro- observed if the mower becomes dull. A second disadvantage is the lack of cold gen-fertilized ryegrass is the preferred A second advantage of ryegrass is the tolerance. More recent cultivar introduc- animal feed for cattle in the Netherlands. relatively rapid germination and emer- tions of turf type perennial ryegrass, how- The early settlers in New Zealand fell and gence rate. Under favourable temperature ever, have increase cold tolerance. Unless burnt the forests, then threw Ryegrass seed conditions of 12 - 25°C, ryegrass will good snow cover can be assure in areas in the ashes to develop one of great intro- emerge in 5 to 8 days. Thus ryegrass is the with severe winters winter kill can be a duced grazing environments in the world. preferred species for oversee ding in the serious problem. late spring or early fall. In oversee ding Ryegrass is susceptible to leaf rusts. In The Ryegrass Family operations rapid germination of the rye- August and early September rust can re- grass increases its competition potential duce the vigour and quality of pure rye- There are about ten species of ryegrass with weed species, such as annual blue- grass stands growing at low levels of which have been botanically identified, grass, which may also be germinating. -

Forage Grass Notes Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium Perenne)

Forage Grass Notes Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne) Introduction Perennial ryegrass is a cool season bunch grass High quality perennial, the choice for pasture where adapted – best adjusted to wet mild temperate climates (New Zealand and Great Britain) Perennial ryegrass can withstand considerable grazing management and remain productive Growth and Morphology Root system is very fibrous, leaves are prominently ribbed on the upper side and shiny on the bottom Leaves are folded in the bud as compared to the fescues which are rolled in the bud Leaf sheaths are red to purple at the base Optimum growth occurs at temperatures 20°- 25°C Grows best on fertile, well-drained soils - does best on soil with pH 6 -7 Much less persistent than orchardgrass, meadow fescue, timothy or bromegrass - susceptible to winter kill and crown r ust- major reasons why its not more highly utilized in Eastern Canada Importance and Use Considered a premier quality grazing species Perennial ryegrass has greater dry matter digestibility than other temperate perennial grass species Produces good dairy pasture, though excellent for all classes of livestock Graze between 20-25 cm tall down to 5 cm stubble - Yield and persistence better under rotational grazing Perennial ryegrass can also be harvested as silage or hay Rapid germination and quick establishment make it a preferred species for sod seeding where adapted Culture and Management Recommended seeding rat es are 7 kg/ha in mixture with 8 kg/ha meadow fescue, 3 kg/ha white clover and 5 kg/ha timothy for pasture Seed in early spring for best results Persistence is best under rotational grazing rather than continuous grazing Apply P&K based on soil test - Nitrogen should be applied in split applications at rates relative to legume content. -

Natural Variation of Flowering Time and Vernalization Responsiveness in Brachypodium Distachyon

Bioenerg. Res. (2010) 3:38–46 DOI 10.1007/s12155-009-9069-3 Natural Variation of Flowering Time and Vernalization Responsiveness in Brachypodium distachyon Christopher J. Schwartz & Mark R. Doyle & Antonio J. Manzaneda & Pedro J. Rey & Thomas Mitchell-Olds & Richard M. Amasino Published online: 7 February 2010 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. 2010 Abstract Dedicated bioenergy crops require certain char- Keywords Biomass . Bioenergy. Brachypodium . acteristics to be economically viable and environmentally Flowering time . Vernalization sustainable. Perennial grasses, which can provide large amounts of biomass over multiple years, are one option being investigated to grow on marginal agricultural land. Introduction Recently, a grass species (Brachypodium distachyon) has been developed as a model to better understand grass Biomass yield is an important component to consider in any physiology and ecology. Here, we report on the flowering program designed to derive energy from plant material. time variability of natural Brachypodium accessions in Plant size and architecture are important biomass yield response to temperature and light cues. Changes in both parameters, and these parameters are often quite variable environmental parameters greatly influence when a given within a given species. Intraspecies variation in biomass accession will flower, and natural Brachypodium accessions yield can be a product of many factors. One such factor is broadly group into winter and spring annuals. Similar to the timing of the transition from vegetative to reproductive what has been discovered in wheat and barley, we find that growth. The switch to flowering causes a diversion of a portion of the phenotypic variation is associated with resources from the continual production of photosynthetic changes in expression of orthologs of VRN genes, and thus, material (leaves) to the terminal production of reproductive VRN genes are a possible target for modifying flowering tissue (flowers, seeds, and fruit). -

Biological Control

Salsola tragus Biological Control: Hasan et al . (2001) report that, "The rust fungus Uromyces salsolae Reichardt (Isolate MW338; IMI No. 372660) was found on S. tragus in western Turkey. The attacked plants were covered with a powdery brown mass of unicellular, globular to oval-shaped urediniospores produced in round to elongated sori on the leaves and stems, and showed much reduced growth. Later in the season, the plants produced unicellular, thick-walled, dark teliospores borne in round to elongated telia. Similarly, the S. tragus plants from the USA, when inoculated in the greenhouse with a water suspension of the urediniospores of U. salsolae , developed brown uredinia and then telia as the disease advanced. The rust has been reported on several species of Salsola in the former-USSR, Israel, Iran, Romania, Australia, France, Pakistan, and Portugal (CAB International Report, unpublished). IMI records also show that the rust has been recorded on other genera of Chenopodiaceae from former USSR, Cyprus, and Romania. During our host specicity studies, the strain of U. salsolae collected by S. Hasan in Turkey was restricted to S. tragus and did not infect any of the other 16 plant species or varieties belonging to six different families that were tested. The fungus severely infected S. tragus plants not only from the USA but also those from Montpellier (France) and Turkey, showing that the rust may not be restricted only to certain biotypes of the weed. The rust fungus, which is highly damaging and effective in killing or severely reducing the growth of the weed under greenhouse conditions, has recently been imported into the USA for further host specificity testing under quarantine conditions. -

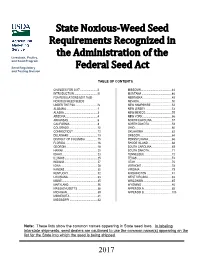

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Federal Seed Act

State Noxious-Weed Seed Requirements Recognized in the Administration of the Livestock, Poultry, and Seed Program Seed Regulatory Federal Seed Act and Testing Division TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGES FOR 2017 ........................ II MISSOURI ........................................... 44 INTRODUCTION ................................. III MONTANA .......................................... 46 FSA REGULATIONS §201.16(B) NEBRASKA ......................................... 48 NOXIOUS-WEED SEEDS NEVADA .............................................. 50 UNDER THE FSA ............................... IV NEW HAMPSHIRE ............................. 52 ALABAMA ............................................ 1 NEW JERSEY ..................................... 53 ALASKA ............................................... 3 NEW MEXICO ..................................... 55 ARIZONA ............................................. 4 NEW YORK ......................................... 56 ARKANSAS ......................................... 6 NORTH CAROLINA ............................ 57 CALIFORNIA ....................................... 8 NORTH DAKOTA ............................... 59 COLORADO ........................................ 10 OHIO .................................................... 60 CONNECTICUT .................................. 12 OKLAHOMA ........................................ 62 DELAWARE ........................................ 13 OREGON............................................. 64 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ................. 15 PENNSYLVANIA................................ -

Inventory of Exotic Plant Species Occurring in Aztec Ruins National Monument

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Inventory of Exotic Plant Species Occurring in Aztec Ruins National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2010/300 ON THE COVER Common salsify (Tragopogon dubius) was one of the most widespread exotic plant species found in the monument during this inventory. Photograph by: Safiya Jetha Inventory of Exotic Plant Species Occurring in Aztec Ruins National Monument Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR—2010/300 Julie E. Korb Biology Department Fort Lewis College 1000 Rim Drive Durango, CO 81301 March 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural re- source topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientif- ically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. Views, statements, findings, conclusions, recommendations, and data in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect views and policies of the National Park Service, U.S. -

Tragus Berteronianus Schultes (Poaceae), a Newly Naturalized Grass in Taiwan

Taiwan J For Sci 31(4): 331-5, 2016 331 Research note Tragus berteronianus Schultes (Poaceae), a Newly Naturalized Grass in Taiwan Ming-Jer Jung,1,3) Chien-Hsun Cheng2) 【Summary】 The newly naturalized genus, Tragus Haller (Poaceae), and its species newly recorded in the flora of Taiwan, T. berteronianus Schultes, which is broadly distributed in Africa, the Americas, and Eurasia, are described and illustrated herein. This grass species was stably found in a coastal region of the Penghu Archipelago, and its habitat and diagnosable characters are also described herein. Key words: Tragus, new record. Jung MJ, Cheng CH. 2016. Tragus berteronianus Schultes (Poaceae), a newly naturalized grass in Taiwan. Taiwan J For Sci 31(4):331-5. 1) Independent researcher, 3rd Fl., No. 27, Lane 13, Jinghua St., Wenshan District, Taipei 11683, Taiwan. 自由研究者,11683台北市文山區景華街13巷27號3樓。 2) No. 1, Zhonghe Village, Cimei Township, Penghu County, 88341, Taiwan. 88341澎湖縣七美鄉中和 村4鄰1號。 3) Corresponding author, e-mail:[email protected] 通訊作者。 Received January 2016, Accepted April 2016. 2016年1月送審 2016年4月通過。 332 Jung and Cheng─Tragus in Taiwan 研究簡報 蝨子草(Tragus berteronianus Schultes, Poaceae), 台灣新歸化禾草 鍾明哲1,3) 鄭謙遜2) 摘要 本文描述台灣禾本科新歸化屬:鋒芒草屬(Tragus Haller)及本屬中廣布於美洲、非洲與歐亞大 陸,及其新紀錄於澎湖群島海濱的禾草:蝨子草(T. berteronianus Schultes),並描述其生育地與鑑定特 徵。 關鍵詞:鋒芒草屬、新紀錄。 鍾明哲,鄭謙遜。2016。蝨子草(Tragus berteronianus Schultes, Poaceae),台灣新歸化禾草。台灣林業 科學31(4):331-5。 The Poaceae is one of the main contribu- .........................................................鋒芒草屬 tors to the flora of Taiwan, and more than 80 Annual or perennial herb. Leaf ligule a alien species have been newly recorded and row of hairs. Panicle constricted, linear and naturalized in Taiwan (Hsu 2000, Boufford et cylindrical in outline, spikelike; branches al. -

Festulolium Hybrid Grass

- DLF Forage Seeds White Paper - Festulolium Hybrid Grass Festulolium is the name for a hybrid forage grass progeny or back crossing the hybrid progeny to its parental developed by crossing Meadow Fescue (Festuca pratense) or lines, a wide range of varieties with varying characteristics and Tall Fescue (Festuca arundinacea) with perennial ryegrass phenotypes has been created. They are classified according (Lolium perenne) or Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum). to their degree of phenotypical similarity to the original par- This enables combining the best properties of the two types ents, not to their genotype heritage. One can regard them as of grass. The resulting hybrids have been classified as: high yielding fescues with improved forage quality or as high yielding, more persistent ryegrasses. Maternal parent Paternal parent Hybrid progeny Festuca arundinacea Lolium multiflorum Festulolium pabulare This genotype make-up of festuloliums can be made Festuca arundinacea Lolium perenne Festulolium holmbergii visual. The chromosomes of festulolium can be isolated and Festuca pratensis Lolium multiflorum Festulolium braunii then colored to show the parental origin of chromosome Festuca pratensis Lolium perenne Festulolium loliaceum sections. It provides a very visual effect of the hybridization between the two species. The fescues contribute qualities such as high dry matter yield, resistance to cold, drought tolerance and persistence, Photo right: Chromosomes of a festulolium, colored to show the while ryegrass is characterized by rapid establishment, parental DNA in the hybrid. good spring growth, good digestibility, sugar content and Green = Ryegrass DNA palatability. The individual festulolium varieties contain Red = Fescue DNA various combinations of these qualities, but all are substantially higher yielding than their parent lines. -

First Record of Eriochloa Villosa (Thunb.) Kunth in Austria and Notes on Its Distribution and Agricultural Impact in Central Europe

BioInvasions Records (2020) Volume 9, Issue 1: 8–16 CORRECTED PROOF Research Article First record of Eriochloa villosa (Thunb.) Kunth in Austria and notes on its distribution and agricultural impact in Central Europe Swen Follak1,*, Michael Schwarz2 and Franz Essl3 1Institute for Sustainable Plant Production, Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety, Vienna, Austria 2Data, Statistics and Risk Assessment, Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety, Vienna, Austria 3Division of Conservation Biology, Vegetation and Landscape Ecology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria Author e-mails: [email protected] (SF), [email protected] (MS), [email protected] (FE) *Corresponding author Citation: Follak S, Schwarz M, Essl F (2020) First record of Eriochloa villosa Abstract (Thunb.) Kunth in Austria and notes on its distribution and agricultural impact in Eriochloa villosa is native to temperate Eastern Asia and is an emerging weed in Central Europe. BioInvasions Records 9(1): Central Europe. Its current distribution in Central Europe was analyzed using 8–16, https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2020.9.1.02 distribution data from the literature and data collected during field trips. In 2019, E. Received: 6 September 2019 villosa was recorded for the first time in Austria. It was found in a crop field in Accepted: 28 November 2019 Unterretzbach in Lower Austria (Eastern Austria). So far, the abundance of E. villosa in the weed communities in Austria and the neighboring Czech Republic is low and Published: 21 February 2020 thus, its present agricultural impact can be considered limited. However, in Romania Handling editor: Quentin Groom and Hungary, the number of records of E. -

Poaceae: Pooideae) Based on Phylogenetic Evidence Pilar Catalán Universidad De Zaragoza, Huesca, Spain

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 31 2007 A Systematic Approach to Subtribe Loliinae (Poaceae: Pooideae) Based on Phylogenetic Evidence Pilar Catalán Universidad de Zaragoza, Huesca, Spain Pedro Torrecilla Universidad Central de Venezuela, Maracay, Venezuela José A. López-Rodríguez Universidad de Zaragoza, Huesca, Spain Jochen Müller Friedrich-Schiller-Universität, Jena, Germany Clive A. Stace University of Leicester, Leicester, UK Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Catalán, Pilar; Torrecilla, Pedro; López-Rodríguez, José A.; Müller, Jochen; and Stace, Clive A. (2007) "A Systematic Approach to Subtribe Loliinae (Poaceae: Pooideae) Based on Phylogenetic Evidence," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 23: Iss. 1, Article 31. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol23/iss1/31 Aliso 23, pp. 380–405 ᭧ 2007, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH TO SUBTRIBE LOLIINAE (POACEAE: POOIDEAE) BASED ON PHYLOGENETIC EVIDENCE PILAR CATALA´ N,1,6 PEDRO TORRECILLA,2 JOSE´ A. LO´ PEZ-RODR´ıGUEZ,1,3 JOCHEN MU¨ LLER,4 AND CLIVE A. STACE5 1Departamento de Agricultura, Universidad de Zaragoza, Escuela Polite´cnica Superior de Huesca, Ctra. Cuarte km 1, Huesca 22071, Spain; 2Ca´tedra de Bota´nica Sistema´tica, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Avenida El Limo´n s. n., Apartado Postal 4579, 456323 Maracay, Estado de Aragua,