Quantitative Restrictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topic 7: Import Quotas and Other Non-Tariff Barriers Introduction and Small-Country Quota Analysis a Quota Is a Limit on Trade, Usually Imports

Topic 7: Import quotas and other non-tariff barriers Introduction and small-country quota analysis A quota is a limit on trade, usually imports. They remain reasonably common in agricultural goods (for example, the US constrains imports of dairy goods, sugar, meats, and other foods). A quota may be imposed either on quantity (a limit on the number of goods that may be imported) or on value (a limit on the dollar value of imports of a particular good). Let’s first see how a quota works, analyzing a small importing nation, which imports textiles (T). Consider this diagram, 1 1 where the quota is distance QT CT = AB. The standard welfare effects are much like a tariff: Domestic price rises to make the amount of the quota equal to the difference in domestic supply and demand. The quota has engineered a shortage on the market, requiring price to rise. There is a loss in consumer surplus of –(a + b +c + d). There is a gain in producer surplus of + a. The area c is what we call “quota rents”. In economics, a “rent” is the payment to owners of a scarce asset in excess of what is required to supply the good. Here, the amount imported under the quota could be imported at the world price D pT* but those goods command a domestic price pT . PT S A B D PT a b c d * * PT S D T 0 1 1 0 QT QT CT CT Quota rents The important question here is how are these quota rents allocated? This will determine the net welfare impacts. -

10Chapter Trade Policy in Developing Countries

M10_KRUG3040_08_SE_C10.qxd 1/10/08 7:26 PM Page 250 10Chapter Trade Policy in Developing Countries o far we have analyzed the instruments of trade policy and its objectives without specifying the context—that is, without saying much about the Scountry undertaking these policies. Each country has its own distinctive history and issues, but in discussing economic policy one difference between countries becomes obvious: their income levels. As Table 10-1 suggests, nations differ greatly in their per-capita incomes. At one end of the spectrum are the developed or advanced nations, a club whose members include Western Europe, several countries largely settled by Europeans (including the United States), and Japan; these countries have per-capita incomes that in many cases exceed $30,000 per year. Most of the world’s population, however, live in nations that are substantially poorer. The income range among these developing countries1 is itself very wide. Some of these countries, such as Singapore, are in fact on the verge of being “graduated” to advanced country status, both in terms of official statistics and in the way they think about themselves. Others, such as Bangladesh, remain desperately poor. Nonetheless, for virtually all developing countries the attempt to close the income gap with more advanced nations has been a central concern of economic policy. Why are some countries so much poorer than others? Why have some coun- tries that were poor a generation ago succeeded in making dramatic progress, while others have not? These are deeply disputed questions, and to try to answer them—or even to describe at length the answers that economists have proposed over the years—would take us outside the scope of this book. -

The Effects of Biotechnology Policy on Trade and Growth

Volume 3 Number 1, 2002/p. 46-61 esteyjournal.com The Estey Centre Journal of International Law and Trade Policy Normalizing Trade Relations with Cuba: GATT-compliant Options for the Allocation of the U.S. Sugar Tariff-rate Quota Devry S. Boughner and Jonathan R. Coleman∗ Office of Industries, U.S. International Trade Commission Even after 40 years of sanctions, there remain huge differences of opinion on U.S.- Cuba relations. One point all sides agree on, however, is that sooner or later sanctions will be removed. Lifting sanctions raises several issues concerning sugar trade between the two countries. With U.S. sugar prices kept significantly higher than world levels, the U.S. market would be highly attractive for Cuban sugar exporters upon the removal of sanctions. Cuba almost certainly would request access to the U.S. sugar market based on U.S. trade obligations under the World Trade Organization (WTO). The purpose of this paper is to suggest the legal context of U.S. obligations under the WTO with respect to sugar imports from Cuba and to present several options for allocation of the U.S. sugar tariff-rate quota to Cuba under a normalized trade relationship. Keywords: allocation options; General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT); historical base period; Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN); substantial interest; tariff-rate quota (TRQ); World Trade Organization (WTO). Editorial Office: 410 22nd St. E., Suite 820, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, S7K 5T6. Phone (306) 244-4800; Fax (306) 244-7839; email: [email protected] 46 D.S. Boughner and J.R. Coleman Introduction .S. -

International Trade Restrictions

International Trade Restrictions Governments restrict international trade to protect domestic producers from competition. Governments use four sets of tools: Tariffs Import quotas Other import barriers Export subsidies © 2010 Pearson Education Canada How Global Markets Work Figure 7.1(a) shows Canadian demand and Canadian supply with no international trade. The price of a T-shirt at $8. Canadian firms produce 4 million T-shirts a year and Canadian consumers buy 4 million T-shirts a year. © 2010 Pearson Education Canada How Global Markets Work Figure 7.1(b) shows the market in Canada with international trade. World demand and world supply of T-shirts determine the world price of a T-shirt at $5. The world price is less than $8, so the rest of the world has a comparative advantage in producing T-shirts. © 2010 Pearson Education Canada How Global Markets Work With international trade, the price of a T-shirt in Canada falls to $5. At $5 a T-shirt, Canadian garment makers produce 2 million T-shirts a year. At $5 a T-shirt, Canadians buy 6 million T-shirts a year. Canada imports 4 million T-shirts a year. © 2010 Pearson Education Canada International Trade Restrictions Tariffs A tariff is a tax on a good that is imposed by the importing country when an imported good crosses its international boundary. For example, the government of India imposes a 100 percent tariff on wine imported from Canada. So when an Indian wine merchant imports a $10 bottle of Ontario wine, he pays the Indian government $10 import duty. -

Economic Development and International Trade : the Japanese Model by Ippei Yamazawa ; Translated and Revised by Ippei Yamazawa

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE THE JAPANESE MODEL BY IPPEI YAMAZAWA TRANSLATED AND REVISED BY IPPEI YAMAZAWA EAST-WEST CENTER RESOURCE SYSTEMS INSTITUTE HONOLULU, HAWAII THE EAST-WEST CENTER is a public, nonprofit educational institution established in Hawaii in 1960 by the United States Congress with a mandate "to promote better relations and understanding among the nations of Asia, the Pacific, and the United States through cooperative study, training, and research.'* Some 2,000 research fellows, graduate students and professionals in busi• ness and government each year work with the Center's international staff on major Asia-Pacific issues relating to population, economic and trade poli• cies, resources and development, the environment, culture and communica• tion, and international relations. Since 1960, more than 25,000 men and women from the region have participated in the Center's cooperative programs. Principal funding for the Center comes from the United States Congress. Support also comes from more than 20 Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. The Center has an international board of governors. Economic Development and International Trade ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE THE JAPANESE MODEL BY IPPEI YAMAZAWA TRANSLATED AND REVISED BY IPPEI YAMAZAWA EAST-WEST CENTER RESOURCE SYSTEMS INSTITUTE HONOLULU, HAWAII Copyright © 1990 by the Resource Systems Institute, East-West Center. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. First published in the Japanese language in 1984 as Ninon no Keizai Hatten to Kokusai BungyO by Toyo Keizai Inc., Tokyo, Japan. -

AFTA) the ASEAN Free Tradearea Arelikely to Be Relativelysmall

WPS2'220 POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 2220 Public Disclosure Authorized A Quantitative Evaluation The static economic benefits of Vietnam's accessionto the of Vietnam's Accession to ASEANFree TradeArea {AFTA) the ASEAN Free TradeArea arelikely to be relativelysmall. The gainsfrom increased Public Disclosure Authorized accessto ASEANmarkets Emiko Fukase would be small,and they Will Martin would be offsetby the costs of trade diversion on the import side. But binding commitments on protection rates under the AFTA plan could provide an important stepping stone to more Public Disclosure Authorized beneficial broader liberalization. Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Development Research Group Trade H November 1999 POLICYRESEARCH WORKING PAPER 2220 Summary findings Vietnam's accession to the ASEAN Free Trade Area AFTA, APEC, and unilateral liberalizations affect (AFTA) has been an important step in its integrati9n into Viietnam's industries in different ways. AFTA appears to the world economy. Fukase and Martin use a ben.efit Vietnam's agriculture by improving its access to multiregion, multisector computable general equilibrium the ASEAN market. model to evaluate how different trade liberalizaticn ' Broad unilateral liberalization beyond AFTA is likely policies of Vietnam and its main trading partners affect to shift labor away from agriculture and certain import- Vietnam's welfare, taking into account the simultaneous competing activities toward relatively labor-intensive impacts on trade, output, and industrial structure. manufacturing. Reduced costs for intermediate inputs They conclude that: will benefit domestic production. 'fhese sectors conform - The static economywide effects of the AFTA to Vietnam's current comparative advantage, and liberalization to which Vietnam is currently committed undertaking broad unilateral liberalization now seems a are small. -

How and Why Do Countries Regulate Trade? Have You Ever Tried to Mail A

How and why do countries regulate trade? Have you ever tried to mail a package to another country at the post office? If so, you probably had to fill out a customs declaration. It asked you to list the items you were sending and to indicate whether they were gifts or goods to be sold. This information is required by customs, the government department responsible for examining goods entering a country and enforcing any trade restrictions on them. Economists have long argued against trade restrictions. Nonetheless, few countries have ever fully embraced free trade, the unrestricted movement of goods and services across borders. Over the years, countries have found many reasons to regulate foreign trade. Many countries restrict imports in order to shield domestic markets from foreign competition. Such behavior is known as protectionism. Countries do this mainly to satisfy political demands at home. There are many types of trade barriers. The four main types are protective tariffs, import quotas, trade embargoes, and voluntary export restraints. The most common type of trade barrier is the protective tariff, a tax on imported goods. Countries use tariffs to raise revenue and to protect domestic industries from competition from cheaper foreign goods. Tariffs are among the easiest taxes to impose, since they arouse little domestic protest and can be easily applied to goods before they enter the country. While protective tariffs may help specific domestic producers, they do not benefit consumers. Tariffs push up the prices of imported goods. So instead of having to lower prices to compete with cheap imports, domestic producers can raise prices to the inflated price level of the imports. -

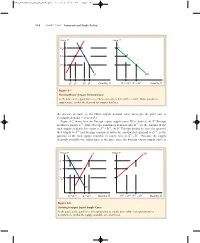

The Absence of Trade, So the Home Import Demand Curve Intercepts the Price Axis at PA (Import Demand = Zero at PA)

M09_KRUG6654_09_SE_C09.QXD 11/3/10 9:21 AM Page 194 194 PART TWO International Trade Policy Price, P Price, P S A PA 2 P 2 1 P 1 D MD S1 S 2 D 2 D 1 Quantity, Q D 2 – S 2 D 1 – S 1 Quantity, Q Figure 9-1 Deriving Home’s Import Demand Curve As the price of the good increases, Home consumers demand less, while Home producers supply more, so that the demand for imports declines. the absence of trade, so the Home import demand curve intercepts the price axis at PA (import demand = zero at PA). Figure 9-2 shows how the Foreign export supply curve XS is derived. At P 1 Foreign producers supply S*1, while Foreign consumers demand only D*1, so the amount of the total supply available for export is S*1 – D*1. At P 2 Foreign producers raise the quantity they supply to S*2 and Foreign consumers lower the amount they demand to D*2, so the quantity of the total supply available to export rises to S*2 – D*2. Because the supply of goods available for export rises as the price rises, the Foreign export supply curve is Price, P S * Price, P XS P 2 P 1 PA* D * D * 2 D *1 S *1 S *2 Quantity, Q S *1 – D *1 S *2 – D *2 Quantity, Q Figure 9-2 Deriving Foreign’s Export Supply Curve As the price of the good rises, Foreign producers supply more while Foreign consumers demand less, so that the supply available for export rises. -

100Questions for Trading with Japan

x 100 Questions for Trading with Japan April 2014 ASEAN PROMOTION CENTRE ON TRADE, INVESTMENT AND TOURISM Under the activity of ASEAN-Japan Centre in FY2013, this book was translated from Japanese into English based on the book “100 Questions for Trading with Japan” issued by Manufactured Imports and Investment Promotion Organization (MIPRO). This material has been prepared based on the information collected in the summer of 2012. The contents might be changed due to the amendments of laws etc., for details, please contact to the address at the end of the book for further information. Preface The ASEAN-Japan Centre is pleased to introduce the book “100 Questions for Trading with Japan” and expresses our gratitude to the Manufactured Imports and Investment Promotion Organization (MIPRO) for sharing this invaluable book which was designed to serve Japanese importers and foreign exporters. This book is written in a question-and-answer form covering the rules and regulations, which govern operations such as customs procedures, foreign payments, etc. Further, the book also takes into account various business sectors, which are of great attention to foreign exporters towards the Japanese market. This may serve as a useful tool for stakeholders from ASEAN member states who wish to export their products into Japan. Since the content of the book was originally designed in Japanese language for Japanese companies, however, readers who are foreigners outside Japan may sometimes “get a feeling” of touching a regulation/instruction/advice for a Japanese entity. For example, a popular phrase “please contact the relevant authority in the nearest prefecture/city where your office is located for further details” is really for a Japanese businessperson rather than for a foreign one. -

Potential Wheat Demand in China: Applicants for Import Quota, U.S

Economic Research Potential Wheat Demand in China: Service Economic Applicants for Import Quota Research Report Number 295 August 2021 Fred Gale Economic Research Service www.ers.usda.gov Recommended citation format for this publication: Fred Gale. ERR-295, August 2021. Potential Wheat Demand in China: Applicants for Import Quota, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Cover images from Getty Images. Shipping photo by author Fred Gale, Senior Economist, REE-ERS Use of commercial and trade names does not imply approval or constitute endorsement by USDA. To ensure the quality of its research reports and satisfy governmentwide standards, ERS requires that all research reports with substantively new material be reviewed by qualified technical research peers. This technical peer review process, coordinated by ERS' Peer Review Coordinating Council, allows experts who possess the technical background, perspective, and expertise to provide an objective and meaningful assessment of the output’s substantive content and clarity of communication during the publication’s review. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. -

Complete Issue

World Customs Journal World World Customs Journal Volume 12, Number 2 Volume September 2018 Volume 12, Number 2 ISSN: 1834-6707 (Print) 1834-6715 (Online) World Customs Journal September 2018 Volume 12, Number 2 update page no International Network of Customs Universities World Customs Journal Published by the Centre for Customs and Excise Studies (CCES), Charles Sturt University, Australia and the University of Münster, Germany in association with the International Network of Customs Universities (INCU) and the World Customs Organization (WCO). The World Customs Journal is a peer-reviewed journal which provides a forum for customs professionals, academics, industry researchers, and research students to contribute items of interest and share research and experiences to enhance its readers’ understanding of all aspects of the roles and responsibilities of Customs. The Journal is published twice a year. The website is at: www.worldcustomsjournal.org. Guidelines for Contributors are included at the end of each issue. More detailed guidance about style is available on the Journal’s website. Correspondence and all items submitted for publication should be sent in Microsoft Word or RTF, as email attachments, to the Editor-in-Chief: [email protected]. ISSN: 1834-6707 (Print) 1834-6715 (Online) Volume 12, Number 2 Published September 2018 © 2018 CCES, Charles Sturt University, Australia and University of Münster, Germany INCU (www.incu.org) is an association that provides the WCO and other organisations with a single point of contact with universities and research institutes that are active in the field of customs research, education and training. Copyright. All rights reserved. Permission to use the content of the World Customs Journal must be obtained from the copyright owner. -

Policies and Trade - Part I: Import Tariffs and Quotas

Policies and Trade - Part I: Import Tariffs and Quotas AED/IS 4540 International Commerce and the World Economy Professor Sheldon [email protected] Tariffs as a Barrier to Trade Consensus among economists on benefits of trade Critical of policies that either create barriers to trade and distort international markets A tariff is classic barrier to trade, i.e., a tax on importing a good or service, usually collected by customs officials at place of entry Two types of tariff: - specific tariff, i.e., $ amount per imported unit - ad valorem tariff, i.e., % of $ value of imported unit Tariffs as a Barrier to Trade For developed countries, tariffs on non-agricultural products successively reduced post-1945 2004, tariff rates averaged 2.5 to 4% on non- agricultural imports into US, Canada, European Union (EU), and Japan Average tariff rates higher for most developing countries, e.g., China’s average tariff on non- agricultural imports was 10% in 2004 Tariff rates on agricultural imports still high, with average rates of 25% (North America), 30% (EU), 34% (Asia-Pacific), and 39% (South America) Effect of a Tariff: Small Country P Importer S Pw+t Sw+t a b c d Pw SW D Q QS Q'S Q'D QD Economic Effects of a Tariff Small importer faces flat (perfectly elastic) world supply curve SW, which shifts to SW +t with a tariff t Domestic supply increases to QS', domestic demand falls to QD', and imports fall to (QS' to QD') Effect of tariff: - loss of consumer surplus = -(a+b+c+d) - gain in producer surplus = +(a) - increased variable costs = - (b) - tariff revenue = +(c) - “deadweight” loss = - (d) - overall loss from tariff = -(b+d) Non-Tariff Barriers A non-tariff barrier (NTB), is any policy used to reduce imports that is not a simple tariff NTBs can take many forms, e.g., import quotas, voluntary export restraints (VERs), product standards etc.