The Temporalization of Time Basic Tendencies in Modern Debate on Time in Philosophy and Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Second Law of Thermodynamics Forbids Time Travel

Cosmology, 2014, Vol. 18. 212-222 Cosmology.com, 2014 The Second Law Of Thermodynamics Forbids Time Travel Marko Popovic Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA Abstract Four space-time coordinates define one thermodynamic parameter - Volume. Cell/ organism growth is one of the most fundamental properties of living creatures. The growth is characterized by irreversible change of the volume of the cell/organism. This irreversible change of volume (growth of the cell/organism) makes the system irreversibly change its thermodynamic state. Irreversible change of the systems thermodynamic state makes impossible return to the previous state characterized by state parameters. The impossibility to return the system to the previous state leads to conclusion that even to artificially turn back the arrow of time (as a parameter), it is not possible to turn back the state of the organism and its surroundings. Irreversible change of thermodynamic state of the organism is also consequence of the accumulation of entropy during life. So even if we find the way to turn back the time arrow it is impossible to turn back the state of the thermodynamic system (including organism) because of irreversibility of thermodynamic/ physiologic processes in it. Keywords: Time travel, Entropy, Living Organism, Surroundings, Irreversibility Cosmology, 2014, Vol. 18. 212-222 Cosmology.com, 2014 1. Introduction The idea of time travel has fascinated humanity since ancient times and can be found in texts as old as Mahabharata and Talmud. Later it continued to be developed in literature (i.e. Dickens' “A Christmas Carol”, or Twain's “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court”…). -

The Arrow of Time Volume 7 Paul Davies Summer 2014 Beyond Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science, Arizona State University, Journal Homepage P.O

The arrow of time Volume 7 Paul Davies Summer 2014 Beyond Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science, Arizona State University, journal homepage P.O. Box 871504, Tempe, AZ 852871504, USA. www.euresisjournal.org [email protected] Abstract The arrow of time is often conflated with the popular but hopelessly muddled concept of the “flow” or \passage" of time. I argue that the latter is at best an illusion with its roots in neuroscience, at worst a meaningless concept. However, what is beyond dispute is that physical states of the universe evolve in time with an objective and readily-observable directionality. The ultimate origin of this asymmetry in time, which is most famously captured by the second law of thermodynamics and the irreversible rise of entropy, rests with cosmology and the state of the universe at its origin. I trace the various physical processes that contribute to the growth of entropy, and conclude that gravitation holds the key to providing a comprehensive explanation of the elusive arrow. 1. Time's arrow versus the flow of time The subject of time's arrow is bedeviled by ambiguous or poor terminology and the con- flation of concepts. Therefore I shall begin my essay by carefully defining terms. First an uncontentious statement: the states of the physical universe are observed to be distributed asymmetrically with respect to the time dimension (see, for example, Refs. [1, 2, 3, 4]). A simple example is provided by an earthquake: the ground shakes and buildings fall down. We would not expect to see the reverse sequence, in which shaking ground results in the assembly of a building from a heap of rubble. -

1 Temporal Arrows in Space-Time Temporality

Temporal Arrows in Space-Time Temporality (…) has nothing to do with mechanics. It has to do with statistical mechanics, thermodynamics (…).C. Rovelli, in Dieks, 2006, 35 Abstract The prevailing current of thought in both physics and philosophy is that relativistic space-time provides no means for the objective measurement of the passage of time. Kurt Gödel, for instance, denied the possibility of an objective lapse of time, both in the Special and the General theory of relativity. From this failure many writers have inferred that a static block universe is the only acceptable conceptual consequence of a four-dimensional world. The aim of this paper is to investigate how arrows of time could be measured objectively in space-time. In order to carry out this investigation it is proposed to consider both local and global arrows of time. In particular the investigation will focus on a) invariant thermodynamic parameters in both the Special and the General theory for local regions of space-time (passage of time); b) the evolution of the universe under appropriate boundary conditions for the whole of space-time (arrow of time), as envisaged in modern quantum cosmology. The upshot of this investigation is that a number of invariant physical indicators in space-time can be found, which would allow observers to measure the lapse of time and to infer both the existence of an objective passage and an arrow of time. Keywords Arrows of time; entropy; four-dimensional world; invariance; space-time; thermodynamics 1 I. Introduction Philosophical debates about the nature of space-time often centre on questions of its ontology, i.e. -

The Origin of the Universe and the Arrow of Time

The Origin of the Universe and the Arrow of Time Sean M Carroll Caltech, Pasadena, CA One of the most obvious facts about the universe is that the past is different from the future. The world around us is full of irreversible processes: we can turn an egg into an omelet, but can't turn an omelet into an egg. Physicists have codified this difference into the Second Law of Thermodynamics: the entropy of a closed system always increases with time. But why? The ultimate explanation is to be found in cosmology: special conditions in the early universe are responsible for the arrow of time. I will talk about the nature of time, the origin of entropy, and how what happened before the Big Bang may be responsible for the arrow of time we observe today. Sean Carroll is a Senior Research Associate in Physics at the California Institute of Technology. He received his Ph.D. in 1993 from Harvard University, and has previously worked as a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Theoretical Physics at MIT and at the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara, as well as on the faculty at the University of Chicago. His research ranges over a number of topics in theoretical physics, focusing on cosmology, field theory, particle physics, and gravitation. Carroll is the author of From Eternity to Here: The Quest for the Ultimate Theory of Time, an upcoming popular-level book on cosmology and the arrow of time. He has also written a graduate textbook, Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity, and recorded a set of lectures on cosmology for the Teaching Company. -

Causality Is an Effect, II

entropy Article Causality Is an Effect, II Lawrence S. Schulman Physics Department, Clarkson University, Potsdam, NY 13699-5820, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Causality follows the thermodynamic arrow of time, where the latter is defined by the direction of entropy increase. After a brief review of an earlier version of this article, rooted in classical mechanics, we give a quantum generalization of the results. The quantum proofs are limited to a gas of Gaussian wave packets. Keywords: causality; arrow of time; entropy increase; quantum generalization; Gaussian wave packets 1. Introduction The history of multiple time boundary conditions goes back—as far as I know—to Schottky [1,2], who, in 1921, considered a single slice of time inadequate for prediction or retrodiction (see AppendixA). There was later work of Watanabe [ 3] concerned with predic- tion and retrodiction. Then, Schulman [4] uses this as a conceptual way to eliminate “initial conditions” prejudice from Gold’s [5] rationale for the arrow of time and Wheeler [6,7] discusses two time boundary conditions. Gell–Mann and Hartle also contributed to this subject [8] and include a review of some previous work. Finally, Aharonov et al. [9,10] pro- posed that this could solve the measurement problem of quantum mechanics, although this is disputed [11]. See also AppendixB. This formalism has also allowed me to come to a conclusion: effect follows cause in the direction of entropy increase. This result is not unanticipated; most likely everything Citation: Schulman, L.S. Causality Is having to do with arrows of time has been anticipated. What is unusual, however, is the an Effect, II. -

The Nature and Origin of Time-Asymmetric Spacetime Structures*

The nature and origin of time-asymmetric spacetime structures* H. D. Zeh (University of Heidelberg) www.zeh-hd.de Abstract: Time-asymmetric spacetime structures, in particular those representing black holes and the expansion of the universe, are intimately related to other arrows of time, such as the second law and the retardation of radiation. The nature of the quantum ar- row, often attributed to a collapse of the wave function, is essential, in particular, for understanding the much discussed "black hole information loss paradox". However, this paradox assumes a new form and might not even occur in a consistent causal treatment that would prevent the formation of horizons and singularities. A “master arrow”, which combines all arrows of time, does not have to be identified with the direction of a formal time parameter that serves to define the dynamics as a succes- sion of global states (a trajectory in configuration or Hilbert space). It may even change direction with respect to a fundamental physical clock, such as the cosmic expansion parameter if this was formally extended either into a future contraction era or to nega- tive "pre-big-bang" values. 1 Introduction Since gravity is attractive, most gravitational phenomena are asymmetric in time: ob- jects fall down or contract under the influence of gravity. In General Relativity, this asymmetry leads to drastically asymmetric spacetime structures, such as future hori- zons and future singularities as properties of black holes. However, since the relativistic and nonrelativistic laws of gravitation are symmetric under time reversal, all time asymmetries must arise as consequences of specific (only seemingly "normal") initial conditions, for example a situation of rest that can be prepared by means of other ar- * arXiv:1012.4708v11. -

Uncertainty and the Communication of Time

UNCERTAINTY AND THE COMMUNICATION OF TIME Systems Research and Behavioral Science 11(4) (1994) 31-51. Loet Leydesdorff Department of Science and Technology Dynamics Nieuwe Achtergracht 166 1018 WV AMSTERDAM The Netherlands Abstract Prigogine and Stengers (1988) [47] have pointed to the centrality of the concepts of "time and eternity" for the cosmology contained in Newtonian physics, but they have not addressed this issue beyond the domain of physics. The construction of "time" in the cosmology dates back to debates among Huygens, Newton, and Leibniz. The deconstruction of this cosmology in terms of the philosophical questions of the 17th century suggests an uncertainty in the time dimension. While order has been conceived as an "harmonie préétablie," it is considered as emergent from an evolutionary perspective. In a "chaology", one should fully appreciate that different systems may use different clocks. Communication systems can be considered as contingent in space and time: substances contain force or action, and they communicate not only in (observable) extension, but also over time. While each communication system can be considered as a system of reference for a special theory of communication, the addition of an evolutionary perspective to the mathematical theory of communication opens up the possibility of a general theory of communication. Key words: time, communication, cosmology, epistemology, self-organization UNCERTAINTY AND THE COMMUNICATION OF TIME Introduction In 1690, Christiaan Huygens noted that: "(I)t is not well to identify certitude with clear and distinct perception, for it is evident that there are, so to speak, various degrees of that clearness and distinctness. We are often deluded in things which we think we certainly understand. -

The Arrow of Time, the Nature of Spacetime, and Quantum Measurement

The arrow of time, the nature of spacetime, and quantum measurement George F R Ellis Mathematics Department, University of Cape Town. October 7, 2011 Abstract This paper extends the work of a previous paper [arXiv:1108.5261v3] on top- down causation and quantum physics, to consider the origin of the arrow of time. It proposes that a ‘past condition’cascades down from cosmological to micro scales, being realised in many microstructures and setting the arrow of time at the quantum level by top-down causation. This physics arrow of time then propagates up, through underlying emergence of higher level structures, to geology, astronomy, engineering, and biology. The appropriate space-time picture to view all this is an emergent block universe (‘EBU’), that recognizes the way the present is di¤erent from both the past and the future. This essential di¤erence is the ultimate reason the arrow of time has to be the way it is. A bonus of this view, entailing the ongoing extension of spacetime as time ‡ows on, is that closed timelike lines are naturally prevented (spacetime singularities will block them o¤). A conclusion of this view is that the process of state vector reduction is central to the ‡ow of time, and is not restricted to laboratory setitngs or any formal process of observation. Contents 1 Quantum theory and the arrow of time 2 2 Foundations 3 2.1 Quantumdynamics............................... 3 2.2 The context: the hierarchy of the structure . 4 2.3 Inter level relations . 4 2.4 Thecentralproposal .............................. 6 3 The arrow of time 7 3.1 Theissue ................................... -

University of California Irvine, Course on Time

Narrative Section of a Successful Proposal The attached document contains the narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful proposal may be crafted. Every successful proposal is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the program guidelines at www.neh.gov/grants/education/enduring-questions for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: NEH Enduring Questions Course on Time Institution: University of California, Irvine Project Director: James Weatherall Grant Program: Enduring Questions 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 302, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 E [email protected] www.neh.gov What won’t fly when you try to kill it? What’s hard to find but often wasted? What heals all wounds but brings only death? Time lends itself to riddles. But perhaps the most puzzling riddle is just this: What is time? It is central to our conceptions of our lives, our selves, and the world around us—and yet capturing it in words seems impossible. -

I Time and Space I

Nature Vol. 253 February 6 1975 485 The Physics of Time Asymmetry. By other towards achieving this happy out Part two is concerned with absolute P. C. W. Davies. Pp. xviii+214. (Surrey come, one is lef,t with an uneasy feeling motion and the theory of relativity, University Press; Leighton Buzzard, that something is still missing. The old tracing the controversy between the 1974.) £6.50. problem of the relationship between the substantival view of Newton that space THIS book is about what is popularly indeterministic world of qu.antum is an entity and the relational views of called the 'arrow of time' but the phy!>ics and the fulJy deterministic Leibniz and Mach that it's not there author does not much like the term world of general relativity seems still at all. The special and general theories because the asymmetry is that of the imperfeatly understood. Actually, Dav of relativ~ty are somewhat geaf,ted on world in respect to time, not of time ies exposes the difficullties in his section to this discussion withou,t, of course, itself. The book is a critical study of 6.3, "Quantum measurement theory". solving the problem. Sklar gives a fine the origin of the asymmetry and of its I cannot but conjecture that the place descriptive account of the theories of role in basic physics. Indeed, it could of the observer will somehow have to reIativ'i>ty, which could well be used by serve as the makting of an excellent be recognised more extensively in for physics students wishing simply to course on the foundations of physics. -

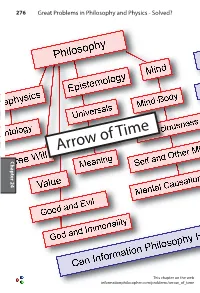

Arrow of Time of Arrow Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Physics and Philosophy in Problems Great 276 Chapterchapter 22 24 Arrow of Time 277

276 Great Problems in Philosophy and Physics - Solved? Chapter 22 Chapter Arrow of Time Chapter 24 Chapter This chapter on the web informationphilosopher.com/problems/arrow_of_time Arrow of Time 277 The Arrow of Time The laws of nature, except the second law of thermodynamics, are symmetric in time. Reversing the time in the dynamical equa- tions of motion simply describes everything going backwards. The second law is different. Entropy must never decrease in time, except statistically and briefly, as Ludwig Boltzmann showed. Many natural processes are apparently irreversible. Irreversibility is intimately connected to the direction of time. Identifying the physical reasons for the observed irreversibility, the origin of irreversibility, would contribute greatly to understanding the apparent asymmetry of nature in time, despite nature's apparently perfect symmetry in space.1 The Thermodynamic Arrow In 1927, Arthur Stanley Eddington coined the term "Arrow of Time" in his book The Nature of the Physical World. He con- nected "Time's Arrow" to the one-way direction of increasing entropy required by the second law of thermodynamics.2 This is now known as the "thermodynamic arrow." In his later work, Eddington identified a "cosmological arrow," the direction in which the universe is expanding,3 which was dis- covered by Edwin Hubble about the time Eddington first defined the thermodynamic arrow. There are now a few other proposed arrows of time, includ- 24 Chapter ing a psychological arrow (our perception of time), a causal arrow (causes precede effects), and a quantum mechanical arrow (elec- troweak decay asymmetries). We can ask whether one arrow is a "master arrow" that all the others are following, or perhaps time itself is just a given property of nature that is otherwise irreducible to something more basic, as is space. -

Hidden Determinism, Probability, and Time's Arrow

Published in: Atmanspacher, H. & Bishop, R. (eds.): Between Chance and Choice. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Determinism Imprint Academic, Thorverton, 2002. Pp. 89–113. Hidden Determinism, Probability, and Time’s Arrow Hans Primas ETH-Zentrum, CH–8092 Z¨urich (Switzerland) Abstract In present-day physics the fundamental dynamical laws are taken as a time-translation-invariant and time-reversal-invariant one-parameter groups of automorphisms of the underlying mathematical structure. In this context-independent and empirically inaccessible description there is no past, present or future, hence no distinction between cause and effect. To get the familiar description in terms of causes and effects, the time-reversal symmetry of the fundamental dynamics has to be broken. Thereby one gets two representations, one satisfying the generally ac- cepted rules of retarded causality (“no effect can precede its cause”). The other one describes the strange rules of advanced causality. For entangled (but not necessarily interacting) quantum systems the arrow of time must have the same direction for all subsystems. But for classical systems, or for classical subsystems of quantum systems, this argument does not hold. As a cosequence, classical systems allow the conceptual possibility of advanced causality in addition to retarded causality. Every mathematically formulated dynamics of statistically reproducible events can be extended to a description in terms of a one-parameter group of automorphisms of an enlarged mathematical structure which describes a fictitious hidden determinism. Consequently, randomness in the sense of mathematical probability theory is only a weak generalization of deter- minism. The popular ideas that in quantum theory there are gaps in the causal chain which allow the accommodation of the freedom of human ac- tion are fantasies which have no basis in present-day quantum mechanics.