Policy Research Working Paper 8992 Manufacturing in Structural Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

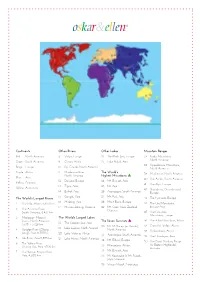

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

Shilliam, Robbie. "Africa in Oceania." the Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections

Shilliam, Robbie. "Africa in Oceania." The Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 169–182. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218788.ch-009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 09:12 UTC. Copyright © Robbie Shilliam 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 9 Africa in Oceania Māui and Legba Hone Taare Tikao, an Ngāi Tahu scholar involved in Te Kotahitanga, the Māori Parliament movement of the late nineteenth century, puts the pieces together: Māui must have visited Africa in one of his epic journeys.1 For once upon a time Māui had turned a thief called Irawaru into a dog, and since then some Māori have considered the dog to be their tuākana (elder sibling). In the 1830s a trading ship from South Africa arrives at Otago harbour. On board is a strange animal that the sailors call a monkey but that the local rangatira (chiefs) recognize to be, in fact, Irawaru. They make speeches of welcome to their elder brother. It is 1924 and the prophet Rātana visits the land that Māui had trodden on so long ago. He finds a Zulu chief driving a rickshaw. He brings the evidence of this debasement back to the children of Tāne/ Māui as a timely warning as to their own standing in the settler state of New Zealand. It is 1969 and Henderson Tapela, president of the African Student’s Association in Aotearoa NZ, reminds the children of Tāne/Māui about their deep-seated relationship with the children of Legba. -

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways

Greens, Beans & Groundnuts African American Foodways City of Bowie Museums Belair Mansion 12207 Tulip Grove Drive Bowie MD 20715 301-809-3089Email: [email protected]/museum Greens, Beans & Groundnuts -African American Foodways Belair Mansion City of Bowie Museums Background: From 1619 until 1807 (when the U.S. Constitution banned the further IMPORTATION of slaves), many Africans arrived on the shores of a new and strange country – the American colonies. They did not come to the colonies by their own choice. They were slaves, captured in their native land (Africa) and brought across the ocean to a very different place than what they knew at home. Often, slaves worked as cooks in the homes of their owners. The food they had prepared and eaten in Africa was different from food eaten by most colonists. But, many of the things that Africans were used to eating at home quickly became a part of what American colonists ate in their homes. Many of those foods are what we call “soul food,” and foods are still part of our diverse American culture today. Food From Africa: Most of the slaves who came to Maryland and Virginia came from the West Coast of Africa. Ghana, Gambia, Nigeria, Togo, Mali, Sierra Leone, Benin, Senegal, Guinea, the Ivory Coast are the countries of West Africa. Foods consumed in the Western part of Africa were (and still are) very starchy, like rice and yams. Rice grew well on the western coast of Africa because of frequent rain. Rice actually grows in water. Other important foods were cassava (a root vegetable similar to a potato), plantains (which look like bananas but are not as sweet) and a wide assortment of beans. -

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

Regional strategy for development cooperation with The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) 2006 – 2008 The Swedish Government resolved on 27 April 2006 that Swedish support for regional development cooperation in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA region) during the period 2006-2008 should be conducted in accordance with the enclosed regional strategy. The Government authorized the Swedish International Development Coope- ration Agency (Sida) to implement in accordance with the strategy and decided that the financial framework for the development cooperation programme should be SEK 400–500 million. Regional strategy for development cooperation with the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) 2006 – 2008 Contents 1. Summary ........................................................................................ 2 2. Conclusions of the regional assessment ........................................... 3 3. Assessment of observations: Conclusions ......................................... 6 4. Other policy areas .......................................................................... 8 5. Cooperation with other donors ........................................................ 10 6. The aims and focus of Swedish development cooperation ................ 11 7. Areas of cooperation with the MENA region ..................................... 12 7.1 Strategic considerations ............................................................. 12 7.2 Cooperation with the Swedish Institute in Alexandria and ............... 14 where relevant with the Section for -

Africa – a Continent of Contrasts

Africa – a continent of contrasts Lesson 7: Africa – looking to the future Key Ideas: a) Modern technology brings both advantages and disadvantages to people in developing countries. b) The richer developed countries in Europe and North America often rely on people in the poorer, developing countries to process and dispose of their electronic waste. Starter activity: Discuss with the class: a) The difficulties of bringing modern technology to countries in Africa. b) The benefits and challenges of using generators or solar power to operate modern technology if electricity is not available. This activity could be conducted with the class as a whole, or small groups of students could discuss the issues amongst themselves before feeding back their thoughts. Main activity: Suggestion 1: Kenya – the impact of mobile phone technology In this activity (downloadable Word worksheet available), students imagine that they are Masai cattle herders who wish to sell some of their herd at market. They consider the benefits of owning a mobile phone for checking market prices and for dealing with cattle illness or rustling. Suggestion 2: Kenya – computers for schools scheme The document accompanying this activity provides links to a variety of articles and a video clip with the aim of encouraging students to think about what happens to their electronic waste. The resources can be divided into two sections, and there are a range of questions that students should be asking about each: a) E-waste When we have finished with a computer (broken or out of date), what do we do with it? The European WEEE directive “imposes the responsibility for the disposal of waste electrical and electronic equipment on the manufacturers of such equipment”. -

Other Rivers

Continents Other Rivers Other Lakes Mountain Ranges Red North America 8 Volga, Europe 22 The Black Sea, Europe 37 Rocky Mountains, North America Green South America 9 Congo, Africa 23 Lake Bajkal, Asia 38 Appalachian Mountains, Beige Europe 10 Rio Grande, North America North America Purple Africa 11 Mackenzie River, The World’s 39 Mackenzie, North America North America Highest Mountains s Blue Asia 40 The Andes, South America 12 Danube, Europe 24 Mt. Everest, Asia Yellow Oceania 41 The Alps, Europe 13 Tigris, Asia 25 K2, Asia White Antarctica 42 Skanderna, (Scandinavia) 14 Eufrat, Asia 26 Aconcagua, South America Europe 15 Ganges, Asia 27 Mt. Fuji, Asia The World’s Longest Rivers 43 The Pyrenees, Europe 16 Mekong, Asia 28 Mont Blanc, Europe 1 The Nile, Africa, 6,650 km 44 The Ural Mountains, 17 Murray-Darling, Oceania 29 Mt. Cook, New Zealand, Europe-Asia 2 The Amazon River, Oceania South America, 6,437 km 45 The Caucasus Mountains, Europe 3 Mississippi- Missouri The World’s Largest Lakes Rivers, North America, The Seven Summits s 46 The Atlas Mountains, Africa 3,778 + 3,726 km 18 The Caspian Sea, Asia 30 Mt. McKinley (or Denali), 47 Great Rift Valley, Africa 19 Lake Superior, North America 4 Yangtze River (Chang North America 48 Drakensberg, Africa Jiang), Asia, 6,300 km 20 Lake Victoria, Africa 31 Aconcagua, South America 49 The Himalayas, Asia 5 Ob River, Asia 5,570 km 21 Lake Huron, North America 32 Mt. Elbrus, Europe 50 The Great Dividing Range 6 The Yellow River 33 Kilimanjaro, Africa (or Eastern Highlands), (Huang Ho), Asia, 4,700 km Australia 7 The Yenisei-Angara River, 34 Mt. -

The Great Rift Valley the Great Rift Valley Stretches from the Floor of the Valley Becomes the Bottom Southwest Asia Through Africa

--------t---------------Date _____ Class _____ Africa South of the Sahara Environmental Case Study The Great Rift Valley The Great Rift Valley stretches from the floor of the valley becomes the bottom Southwest Asia through Africa. The valley of a new sea. is a long, narrow trench: 4,000 miles (6,400 The Great Rift Valley is the most km) long but only 30-40 miles (48-64 km) extensive rift on the Earth's surface. For wide. It begins in Southwest Asia, where 30 million years, enormous plates under it is occupied by the Jordan River and neath Africa have been pulling apart. the Dead Sea. It widens to form the basin Large earthquakes have rumbled across of the Red Sea. In Africa, it splits into an the land, causing huge chunks of the eastern and western branch. The Eastern Earth's crust to collapse. Rift extends all the way to the shores of Year after year, the crack that is the the Indian Ocean in Mozambique. Great Rift Valley widens a bit. The change is small and slow-just a few centimeters A Crack in the Ea rth Most valleys are carved by rivers, but the Great Rift Valley per year. Scientists believe that eventually is different. Violent forces in the Earth the continent will rip open at the Indian caused this valley. The rift is actually Ocean. Seawater will pour into the rift, an enormous crack in the Earth's crust. flooding it all the way north to the Red Along the crack, Africa is slowly but surely splitting in two. -

The Case of Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa

23 Regionalism and Interregionalism: The case of Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa Frank Mattheis Centre for the Study of Governance Innovation, University of Pretoria ABSTRACT In their extra-regional outreach Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa rarely make each other a priority. However, since the end of the Cold War there has been an increasing amount of political efforts to strengthen ties on a region-to-region basis. This paper argues that this rapprochement has been facilitated by the emergence of two regional projects following a similar logic in a post-Cold War context: the Southern African Development Community and the Common Market of the Southern Cone. At the same time, both projects face serious limitations of actorness that are illustrative of the confined space for interregionalism across the South Atlantic. An analysis of the formalised initiatives on political, economic and trade issues between the two regions concludes that these are characterised by transregional and partly pure forms of interregionalism and that most initiatives are heavily shaped by the leading role of Brazil. ATLANTIC FUTURE WORKING PAPER 23 Table of contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 3 2. Regionalisms in Latin America and Southern Africa .............................................. 4 2.1 Historic region-building: continuities, cycles and ruptures .................................... 4 2.2 Contemporary regionalisms ................................................................................ -

Rift-Valley-1.Pdf

R E S O U R C E L I B R A R Y E N C Y C L O P E D I C E N T RY Rift Valley A rift valley is a lowland region that forms where Earth’s tectonic plates move apart, or rift. G R A D E S 6 - 12+ S U B J E C T S Earth Science, Geology, Geography, Physical Geography C O N T E N T S 9 Images For the complete encyclopedic entry with media resources, visit: http://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/rift-valley/ A rift valley is a lowland region that forms where Earth’s tectonic plates move apart, or rift. Rift valleys are found both on land and at the bottom of the ocean, where they are created by the process of seafloor spreading. Rift valleys differ from river valleys and glacial valleys in that they are created by tectonic activity and not the process of erosion. Tectonic plates are huge, rocky slabs of Earth's lithosphere—its crust and upper mantle. Tectonic plates are constantly in motion—shifting against each other in fault zones, falling beneath one another in a process called subduction, crashing against one another at convergent plate boundaries, and tearing apart from each other at divergent plate boundaries. Many rift valleys are part of “triple junctions,” a type of divergent boundary where three tectonic plates meet at about 120° angles. Two arms of the triple junction can split to form an entire ocean. The third, “failed rift” or aulacogen, may become a rift valley. -

AFRICA-EUROPE ECONOMIC COOPERATION Using the Opportunities for Reorientation the EU’S Economic Relations with Africa

The paper examines the current status of EU-African economic relations and the EU’s Joint Communication »Towards a Comprehensive Strategy with Africa« (CSA) in this pivotal year 2020. AFRICA-EUROPE The renewal between the Eu ropean Union and the Afri- can continent has been over- ECONOMIC shadowed by the global coro- navirus crisis. The consequen - ces of the pandemic for the COOPERATION African continent are so far- reaching that economic coop- eration between Africa and Using the Opportunities for Reorientation the EU must be readjusted. Robert Kappel May 2020 The CSA needs to be funda- mentally revised above all to overcome the asymmetrical dependence and power rela- tions between Africa and the European Union. AFRICA-EUROPE ECONOMIC COOPERATION Using the Opportunities for Reorientation THE EU’S Economic RELations WitH Africa The European Union’s relations with the African continent and Africa reached a total value of 235 billion euros (32 per face particular challenges. Unexpectedly, the negotiations cent of Africa’s total trade). Trade relations between the EU between the partners are now being put through a special and African countries, while very close, remain extremely rehearsal. The global spread of COVID-19 has led to eco- asymmetric: almost 30 per cent of all African exports go to nomic crises in Europe, China and the USA, as well as on the EU, while Africa is a relatively insignificant market for the African continent. This economic crisis also affects the the EU. The share of imports from Europe has stagnated at EU’s external trade relations with Africa. The EU-African around 0.5 per cent, depending on the African region. -

A GREATER MIDDLE EAST Mediterranean Studies

A GREATER MIDDLE EAST Mediterranean Studies Course contact hours: 45 Recommended credits: 6 ECTS – 3 US credits OBJECTIVES The goal of this course is to offer an in-depth introduction to a fundamental geostrategic area since the end of World War II, that is, the Middle East. The title of this course refers to both, Carter Doctrine (1980) and George W. Bush’s Greater Middle East and North Africa Initiative (2004), by which the Middle East region is studied with North Africa, the Horn of Africa and Central Asia, covering the Area of Influence of the Central Command. Since studying all the countries in the region will be impossible, three countries will be studied in depth in order to understand all the important elements that built the different political and social projects in the region. The countries studied will be: first, Pakistan and its complicated independence from Great Britain in 1947 and the political evolution of this country; second, Iran and its evolution from the years of the Pahlavi Dynasty to the war between Iran and Iraq; third, Afghanistan and its traumatic experience with war since the Soviet invasion. LEARNING OUTCOMES Students should demonstrate: responsibility & accountability, independence & interdependence, goal orientation, self-confidence, resilience, appreciation of differences. They will be able to communicate their ideas and research findings in both oral and written forms. CONTENT The Greater Middle East Region, now and then 1 The End of the Ottoman Empire, 1918-1923 North Africa, 1918-1950s The Middle East,