Quiet Debut'' of the Double Helix: a Bibliometric and Methodological

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francois Jacob Memorial

RETROSPECTIVE RETROSPECTIVE Francois Jacob memorial Arthur B. Pardee1 Department of Adult Oncology, Dana-Farber Institute, Boston, MA 02115 Dr. Francois Jacob is one of a handful of the DNA would integrate into the bacterial chro- 20th century’smostdistinguishedlifescien- mosome and remain dormant or, at other tists. His research with Dr. Jacques Monod, times, would kill the cell. like that of Watson and Crick, provided the Jacob’s next major contribution, in collab- foundations for understanding mechanisms oration with Dr. Jacques Monod, was to in- of genetic regulation of life processes such vestigate how a gene is regulated. Remark- as cell differentiation and defects in diseases. ably, native E. coli synthesize β-galactosidase Jacob joined the College de France in 1964 only when lactose is available. Some mutated and shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology bacteria can make the enzyme in the absence or Medicine 1965 with Jacques Monod of inducer. Monod’s initial idea was that and Andre Lwoff. He was elected to the these constitutive bacteria activate the gene National Academy of Sciences (NAS) USA by synthesizing an intracellular lactose-like in 1969. inducer molecule. Jacob was born in 1920 in a French Jewish To investigate this model, interrupted family; his grandfather was a four-star gen- mating was applied to bring the β-galactosi- eral. He began to study medicine before dase gene of a donor bacterium into a consti- World War II, in which he served as a mil- tutive receptor. According to the induction itary officer in the Free French Army and was model, the mated cell should produce en- badly wounded in an air raid. -

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Interpreting the History of Evolutionary Biology Through a Kuhnian Prism: Sense Or Nonsense?

Interpreting the History of Evolutionary Biology through a Kuhnian Prism: Sense or Nonsense? Koen B. Tanghe Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Lieven Pauwels Department of Criminology, Criminal Law and Social Law, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Alexis De Tiège Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Johan Braeckman Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences, Universiteit Gent, Belgium Traditionally, Thomas S. Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) is largely identified with his analysis of the structure of scientific revo- lutions. Here, we contribute to a minority tradition in the Kuhn literature by interpreting the history of evolutionary biology through the prism of the entire historical developmental model of sciences that he elaborates in The Structure. This research not only reveals a certain match between this model and the history of evolutionary biology but, more importantly, also sheds new light on several episodes in that history, and particularly on the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), the construction of the modern evolutionary synthesis, the chronic discontent with it, and the latest expression of that discon- tent, called the extended evolutionary synthesis. Lastly, we also explain why this kind of analysis hasn’t been done before. We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive review, as well as the editor Alex Levine. Perspectives on Science 2021, vol. 29, no. 1 © 2021 by The Massachusetts Institute of Technology https://doi.org/10.1162/posc_a_00359 1 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/posc_a_00359 by guest on 30 September 2021 2 Evolutionary Biology through a Kuhnian Prism 1. -

DNA: the Timeline and Evidence of Discovery

1/19/2017 DNA: The Timeline and Evidence of Discovery Interactive Click and Learn (Ann Brokaw Rocky River High School) Introduction For almost a century, many scientists paved the way to the ultimate discovery of DNA and its double helix structure. Without the work of these pioneering scientists, Watson and Crick may never have made their ground-breaking double helix model, published in 1953. The knowledge of how genetic material is stored and copied in this molecule gave rise to a new way of looking at and manipulating biological processes, called molecular biology. The breakthrough changed the face of biology and our lives forever. Watch The Double Helix short film (approximately 15 minutes) – hyperlinked here. 1 1/19/2017 1865 The Garden Pea 1865 The Garden Pea In 1865, Gregor Mendel established the foundation of genetics by unraveling the basic principles of heredity, though his work would not be recognized as “revolutionary” until after his death. By studying the common garden pea plant, Mendel demonstrated the inheritance of “discrete units” and introduced the idea that the inheritance of these units from generation to generation follows particular patterns. These patterns are now referred to as the “Laws of Mendelian Inheritance.” 2 1/19/2017 1869 The Isolation of “Nuclein” 1869 Isolated Nuclein Friedrich Miescher, a Swiss researcher, noticed an unknown precipitate in his work with white blood cells. Upon isolating the material, he noted that it resisted protein-digesting enzymes. Why is it important that the material was not digested by the enzymes? Further work led him to the discovery that the substance contained carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and large amounts of phosphorus with no sulfur. -

A Short History of Botany in the United States</Article

would have extended the value of the classes (the chapter on plant ecology book to the layman, the high school to my environmental biology class, for ScienceFilmstrips biology student, and even the elemen- example) in order to give students a tary-school child. fine historical overview of the particu- R. E. Barthelemy lar discipline's development in this BIOLOGY CHEMISTRY University of Minnesota country. Meanwhile I read the book PHYSICS MICROBIOLOGY Minneapolis piecemeal myself for biohistorical ap- ATOMICENERGY preciation and background; it shouldn't at one sit- ATOMICCONCEPT be read from cover to cover HISTORYAND PHILOSOPHY ting! HOWTO STUDY Never before has such a fund of di- on American botani- GENERALSCIENCE A SHORT HISTORY OF BOTANY IN THE UNITED verse information in FIGURE DRAWING STATES, ed. by Joseph Ewan. 1969. cal endeavor been brought together LABORATORYSAFETY Hafner Publishing Co., N.Y. 174 pp. one handy volume. We might hope that American zoologists, undaunted by HEALTHAND SAFETY(Campers) Price not given. Engelmann of St. having been upstaged, can shortly man- SAFETYIN AN ATOMICATTACK In 1846 George Louis, after finally receiving some fi- age to compile a comparable volume SCHOOLBUS SAFETY nancial encouragement for the pursuit for their discipline. BICYCLESAFETY of botany in the American West, opti- Richard G. Beidleman Colorado College mistically wrote that he could "hope a Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/abt/article-pdf/32/3/178/339753/4442993.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 WATERCONSERVATION Springs little more from this country for sci- Colorado ence." Today, Engelmann would be de- CARL LINNAEUS, Alvin and Virginia Ask for free folder and information lighted and amazed by what his adopted by Silverstein. -

Physics Today - February 2003

Physics Today - February 2003 Rosalind Franklin and the Double Helix Although she made essential contributions toward elucidating the structure of DNA, Rosalind Franklin is known to many only as seen through the distorting lens of James Watson's book, The Double Helix. by Lynne Osman Elkin - California State University, Hayward In 1962, James Watson, then at Harvard University, and Cambridge University's Francis Crick stood next to Maurice Wilkins from King's College, London, to receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their "discoveries concerning the molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living material." Watson and Crick could not have proposed their celebrated structure for DNA as early in 1953 as they did without access to experimental results obtained by King's College scientist Rosalind Franklin. Franklin had died of cancer in 1958 at age 37, and so was ineligible to share the honor. Her conspicuous absence from the awards ceremony--the dramatic culmination of the struggle to determine the structure of DNA--probably contributed to the neglect, for several decades, of Franklin's role in the DNA story. She most likely never knew how significantly her data influenced Watson and Crick's proposal. Franklin was born 25 July 1920 to Muriel Waley Franklin and merchant banker Ellis Franklin, both members of educated and socially conscious Jewish families. They were a close immediate family, prone to lively discussion and vigorous debates at which the politically liberal, logical, and determined Rosalind excelled: She would even argue with her assertive, conservative father. Early in life, Rosalind manifested the creativity and drive characteristic of the Franklin women, and some of the Waley women, who were expected to focus their education, talents, and skills on political, educational, and charitable forms of community service. -

DICTIONARY of the HISTORY of SCIENCE Subject Editors

DICTIONARY OF THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE Subject Editors Astronomy Michael A. Hoskin, Churchill College, Cambridge. Biology Richard W. Burkhardt, Jr, Department of History, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Chemistry William H. Brock, Victorian Studies Centre, University of Leicester. Earth sciences Roy Porter, W ellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London. Historiography Steven Shapin, & sociology Science Studies Unit, of science University of Edinburgh. Human Roger Smith, sciences Department of History, University of Lancaster. Mathematics Eric J. Aiton, Mathematics Faculty, Manchester Polytechnic. Medicine William F. Bynum, W ellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London. Philosophy Roy Bhaskar, of science School of Social Sciences, University of Sussex. Physics John L. Heilbron, Office for History of Science & Technology, University of California, Berkeley. DICTIONARY OF THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE edited by W.EBynum E.J.Browne Roy Porter M © The Macmillan Press Ltd 1981 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1981 978-0-333-29316-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. First published 1981 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN 978-1-349-05551-7 ISBN 978-1-349-05549-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-05549-4 Typeset by Computacomp (UK) Ltd, Fort William, Scotland Macmillan Consultant Editor Klaus Boehm Contents Introduction vii Acknowledgements viii Contributors X Analytical table of contents xiii Bibliography xxiii Abbreviations xxxiv Dictionary Bibliographical index 452 Introduction How is the historical dimension of science relevant to understanding its place in our lives? It is widely agreed that our present attitudes and ideas about religion, art, or morals are oriented the way they are, and thus related to other beliefs, because of their history. -

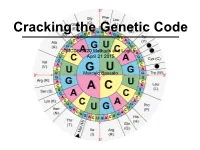

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

The Eighth Day of Creation”: Looking Back Across 40 Years to the Birth of Molecular Biology and the Roots of Modern Cell Biology

“The Eighth Day of Creation”: looking back across 40 years to the birth of molecular biology and the roots of modern cell biology Mark Peifer1 1 Department of Biology and Curriculum in Genetics and Molecular Biology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, CB#3280, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3280, USA * To whom correspondence should be addressed Email: [email protected] Phone: (919) 962-2272 1 Forty years ago, Horace Judson’s “The Eight Day of Creation” was published, a book vividly recounting the foundations of modern biology, the molecular biology revolution. This book inspired many in my generation. The anniversary provides a chance for a new generation to take a look back, to see how science has changed and hasn’t changed. Many central players in the book, including Sydney Brenner, Seymour Benzer and Francois Jacob, would go on to be among the founders of modern cell, developmental, and neurobiology. These players come alive via their own words, as complex individuals, both heroes and anti-heroes. The technologies and experimental approaches they pioneered, ranging from cell fractionation to immunoprecipitation to structural biology, and the multidisciplinary approaches they took continue to power and inspire our work today. In the process, Judson brings out of the shadows the central roles played by women in many of the era’s discoveries. He provides us with a vision of how science and scientists have changed, of how many things about our endeavor never change, and how some new ideas are perhaps not as new as we’d like to think. 2 In 1979 Horace Judson completed a ten-year project about cell and molecular biology’s foundations, unveiling “The Eighth Day of Creation”, a book I view as one of the most masterful evocations of a scientific revolution (Judson, 1979). -

In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick Discovered the Structure of DNA in the Now-Famous Scientific Narrative Known As the “Race Towards the Double Helix”

THE NARRATIVES OF SCIENCE: LITERARY THEORY AND DISCOVERY IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY PRIYA VENKATESAN In 1953 in England James Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA in the now-famous scientific narrative known as the “race towards the double helix”. Meanwhile in France, Roland Barthes published his first book, Writing Degree Zero, on literary theory, which became the intellectual precursor for the new human sciences that were developing based on Saussurean linguistics. The discovery by Watson and Crick of the double helix marked a definitive turning point in the development of the life sciences, paving the way for the articulation of the genetic code and the emergence of molecular biology. The publication by Barthes was no less significant, since it served as an exemplar for elucidating how literary narratives are structured and for formulating how textual material is constructed. As Françoise Dosse notes, Writing Degree Zero “received unanimous acclaim and quickly became a symptom of new literary demands, a break with tradition”.1 Both the work of Roland Barthes and Watson and Crick served as paradigms in their respective fields. Semiotics, the field of textual analysis as developed by Barthes in Writing Degree Zero, offered a new direction in the structuring of narrative whereby each distinct unit in a story formed a “code” or “isotopy” that categorizes the formal elements of the story. The historical concurrence of the discovery of the double helix and the publication of Writing Degree Zero may be mere coincidence, but this essay is an exploration of the intellectual influence that both events may have had on each other, since both the discovery of the double helix and Barthes’ publication gave expression to the new forms of knowledge 1 Françoise Dosse, History of Structuralism: The Rising Sign, 1945-1966, trans. -

Cover June 2011

z NOBEL LAUREATES IN Qui DNA RESEARCH n u SANGRAM KESHARI LENKA & CHINMOYEE MAHARANA F 1. Who got the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1933) for discovering the famous concept that says chromosomes carry genes? a. Gregor Johann Mendel b. Thomas Hunt Morgan c. Aristotle d. Charles Darwin 5. Name the Nobel laureate (1959) for his discovery of the mechanisms in the biological 2. The concept of Mutations synthesis of ribonucleic acid and are changes in genetic deoxyribonucleic acid? information” awarded him a. Arthur Kornberg b. Har Gobind Khorana the Nobel Prize in 1946: c. Roger D. Kornberg d. James D. Watson a. Hermann Muller b. M.F. Perutz c. James D. Watson 6. Discovery of the DNA double helix fetched them d. Har Gobind Khorana the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1962). a. Francis Crick, James Watson, Rosalind Elsie Franklin b. Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Willkins c. James Watson, Maurice Willkins, Rosalind Elsie Franklin 3. Identify the discoverer and d. Maurice Willkins, Rosalind Elsie Franklin and Francis Crick Nobel laureate of 1958 who found DNA in bacteria and viruses. a. Louis Pasteur b. Alexander Fleming c. Joshua Lederberg d. Roger D. Kornberg 4. A direct link between genes and enzymatic reactions, known as the famous “one gene, one enzyme” hypothesis, was put forth by these 7. They developed the theory of genetic regulatory scientists who shared the Nobel Prize in mechanisms, showing how, on a molecular level, Physiology or Medicine, 1958. certain genes are activated and suppressed. Name a. George Wells Beadle and Edward Lawrie Tatum these famous Nobel laureates of 1965. -

Balcomk41251.Pdf (558.9Kb)

Copyright by Karen Suzanne Balcom 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Karen Suzanne Balcom Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine Committee: E. Glynn Harmon, Supervisor Julie Hallmark Billie Grace Herring James D. Legler Brooke E. Sheldon Discovery and Information Use Patterns of Nobel Laureates in Physiology or Medicine by Karen Suzanne Balcom, B.A., M.L.S. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2005 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my first teachers: my father, George Sheldon Balcom, who passed away before this task was begun, and to my mother, Marian Dyer Balcom, who passed away before it was completed. I also dedicate it to my dissertation committee members: Drs. Billie Grace Herring, Brooke Sheldon, Julie Hallmark and to my supervisor, Dr. Glynn Harmon. They were all teachers, mentors, and friends who lifted me up when I was down. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee: Julie Hallmark, Billie Grace Herring, Jim Legler, M.D., Brooke E. Sheldon, and Glynn Harmon for their encouragement, patience and support during the nine years that this investigation was a work in progress. I could not have had a better committee. They are my enduring friends and I hope I prove worthy of the faith they have always showed in me. I am grateful to Dr.