Neutral and Stable Equilibria of Genetic Systems and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

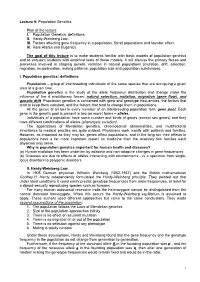

Lecture 9: Population Genetics

Lecture 9: Population Genetics Plan of the lecture I. Population Genetics: definitions II. Hardy-Weinberg Law. III. Factors affecting gene frequency in a population. Small populations and founder effect. IV. Rare Alleles and Eugenics The goal of this lecture is to make students familiar with basic models of population genetics and to acquaint students with empirical tests of these models. It will discuss the primary forces and processes involved in shaping genetic variation in natural populations (mutation, drift, selection, migration, recombination, mating patterns, population size and population subdivision). I. Population genetics: definitions Population – group of interbreeding individuals of the same species that are occupying a given area at a given time. Population genetics is the study of the allele frequency distribution and change under the influence of the 4 evolutionary forces: natural selection, mutation, migration (gene flow), and genetic drift. Population genetics is concerned with gene and genotype frequencies, the factors that tend to keep them constant, and the factors that tend to change them in populations. All the genes at all loci in every member of an interbreeding population form gene pool. Each gene in the genetic pool is present in two (or more) forms – alleles. Individuals of a population have same number and kinds of genes (except sex genes) and they have different combinations of alleles (phenotypic variation). The applications of Mendelian genetics, chromosomal abnormalities, and multifactorial inheritance to medical practice are quite evident. Physicians work mostly with patients and families. However, as important as they may be, genes affect populations, and in the long run their effects in populations have a far more important impact on medicine than the relatively few families each physician may serve. -

Hemizygous Or Haploid Sex Diploid Sex

9781405132770_4_002.qxd 1/19/09 2:22 PM Page 16 Table 2.1 Punnett square to predict genotype frequencies for loci on sex chromosomes and for all loci in males and females of haplo-diploid species. Notation in this table is based on birds where the sex chromosomes are Z and W (ZZ males and ZW females) with a diallelic locus on the Z chromosome possessing alleles A and a at frequencies p and q, respectively. In general, genotype frequencies in the homogametic or diploid sex are identical to Hardy–Weinberg expectations for autosomes, whereas genotype frequencies are equal to allele frequencies in the heterogametic or haploid sex. Hemizygous or haploid sex Diploid sex Genotype Gamete Frequency Genotype Gamete Frequency ZW Z-A p ZZ Z-A p Z-a q Z-a q W Expected genotype frequencies under random mating Homogametic sex Z-A Z-A p2 Z-A Z-a 2pq Z-a Z-a q2 Heterogametic sex Z-A W p Z-a W q ·· 9781405132770_4_002.qxd 1/19/09 2:22 PM Page 19 Table 2.2 Example DNA profile for three simple tandem repeat (STR) loci commonly used in human forensic cases. Locus names refer to the human chromosome (e.g. D3 means third chromosome) and chromosome region where the SRT locus is found. Locus D3S1358 D21S11 D18S51 Genotype 17, 18 29, 30 18, 18 ·· 9781405132770_4_002.qxd 1/19/092:22PMPage20 Table 2.3 Allele frequencies for nine STR loci commonly used in forensic cases estimated from 196 US Caucasians sampled randomly with respect to geographic location. -

Popgen7: Genetic Drift

PopGen7: Genetic Drift Sampling error Before taking on the notion of genetic drift in populations, let’s first take a look at sampling variation. Let’s consider the age-old coin tossing experiment. Assume a fair coin with p = ½. If you sample many times the most likely single outcome = ½ heads. The overall most likely outcome ≠ ½ heads. This is a binomial sampling problem. ⎛n⎞ k n−k P = ⎜ ⎟()()1/ 2 1/ 2 ⎝k ⎠ ⎛n⎞ n! ⎜ ⎟ = ⎝k ⎠ k!()n − k ! n is the number of flips k is the number of successes Let’s look at the probability of the following: k heads from n flips Probability k =5 from n = 10 0.246 k =6 from n = 10 0.205 So, the most likely single outcome is ½ heads (with p = 0.246), the overall likelihood of observing something other than ½ heads is higher (p = 1 – 0.246 = 0.754) The good news is that as we increase the sample size the likelihood of observing something very close to the expected frequency, E(p) = 0.5, goes up. The probability of a given frequency of heads from n flips of the coin is: N flips p <0.35 p = 0.35-0.45 p = 0.45-0.55 p = 0.55-0.65 p <0.65 variance 10 0.16 0.21 0.25 0.21 0.16 0.025 20 0.06 0.19 0.50 0.19 0.06 0.0125 50 0.002 0.16 0.68 0.16 0.002 0.005 It is clear that sample size N is important. -

A Fundamental Relationship Between Genotype Frequencies and Fitnesses

Copyright Ó 2008 by the Genetics Society of America DOI: 10.1534/genetics.108.093518 A Fundamental Relationship Between Genotype Frequencies and Fitnesses Joseph Lachance1 Graduate Program in Genetics, Department of Ecology and Evolution, State University of New York, Stony Brook, New York 11794-5222 Manuscript received July 3, 2008 Accepted for publication August 7, 2008 ABSTRACT The set of possible postselection genotype frequencies in an infinite, randomly mating population is found. Geometric mean heterozygote frequency divided by geometric mean homozygote frequency equals two times the geometric mean heterozygote fitness divided by geometric mean homozygote fitness. The ratio of genotype frequencies provides a measure of genetic variation that is independent of allele frequencies. When this ratio does not equal two, either selection or population structure is present. Within-population HapMap data show population-specific patterns, while pooled data show an excess of homozygotes. HAT patterns of genetic variation are possible within the set of possible postselection genotype frequencies is W a population, and how does natural selection affect derived. Much like how the Hardy–Weinberg principle these patterns? R. A. Fisher remarked ‘‘it is often conve- describes population genetic states in the absence of nient to consider a natural population not so much as an selection, this novel equation describes population genetic aggregate of living individuals but as an aggregate of gene states in the presence of selection. In the context of ratios’’ (Fisher 1953, p. 515). This mathematical abstrac- genotype-frequency space, this is a multidimensional tion allows key questions in evolutionary genetics to be surface, the curvature of which is influenced by natural addressed. -

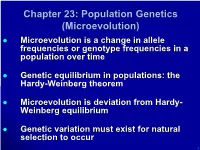

Chapter 23: Population Genetics (Microevolution) Microevolution Is a Change in Allele Frequencies Or Genotype Frequencies in a Population Over Time

Chapter 23: Population Genetics (Microevolution) Microevolution is a change in allele frequencies or genotype frequencies in a population over time Genetic equilibrium in populations: the Hardy-Weinberg theorem Microevolution is deviation from Hardy- Weinberg equilibrium Genetic variation must exist for natural selection to occur . • Explain what terms in the Hardy- Weinberg equation give: – allele frequencies (dominant allele, recessive allele, etc.) – each genotype frequency (homozygous dominant, heterozygous, etc.) – each phenotype frequency . Chapter 23: Population Genetics (Microevolution) Microevolution is a change in allele frequencies or genotype frequencies in a population over time Genetic equilibrium in populations: the Hardy-Weinberg theorem Microevolution is deviation from Hardy- Weinberg equilibrium Genetic variation must exist for natural selection to occur . Microevolution is a change in allele frequencies or genotype frequencies in a population over time population – a localized group of individuals capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring, and that are more or less isolated from other such groups gene pool – all alleles present in a population at a given time phenotype frequency – proportion of a population with a given phenotype genotype frequency – proportion of a population with a given genotype allele frequency – proportion of a specific allele in a population . Microevolution is a change in allele frequencies or genotype frequencies in a population over time allele frequency – proportion of a specific allele in a population diploid individuals have two alleles for each gene if you know genotype frequencies, it is easy to calculate allele frequencies example: population (1000) = genotypes AA (490) + Aa (420) + aa (90) allele number (2000) = A (490x2 + 420) + a (420 + 90x2) = A (1400) + a (600) freq[A] = 1400/2000 = 0.70 freq[a] = 600/2000 = 0.30 note that the sum of all allele frequencies is 1.0 (sum rule of probability) . -

Glossary in Evolutionary Biology Compiled by Prof

Glossary evolutionary biology. Page 1 Glossary in Evolutionary Biology Compiled by Prof. Dieter Ebert This list contains terms, which a student in evolutionary biology should know. The terms denoted with an * are for an advanced level (Courses in evolutionary and quantitative genetics). This Glossary has been compiled with the help of the following books: • J.R. Krebs & N.B. Davies; An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology. 3. Ed., Blackwell UK. 1993. • S.C. Stearns & R.F. Hoeckstra; Evolution: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. 2005. • D.A. Roff; The Evolution of life histories. Chapman & Hall. 1992. ____________________________________________________________________ Adaptation: A state that evolved because it improved reproductive performance, to which survival contributes. Also the process that produces that state. Adaptive evolution: The process of change in a population driven by variation in reproductive success that is correlated with heritable variation in a trait. *Additive genetic variance: The part of total genetic variance that can be modelled by allelic effects whose influence on the phenotype in heterozygotes is additive (Additive means that the phenotype of the heterozygote is halfway between the phenotype of the two homozygotes). This part of genetic variance determines the response to selection by quantitative traits. Aging (=Ageing): (See Senescence). Allele: One of the different homologous forms of a single gene; at the molecular level, a different DNA sequence at the same place in the chromosome. Allele frequency: Proportion the copies of a given allele among all alleles at the locus of interest. Allometry: Relationship between the size of two organisms or their parts. E.g. larger organisms produce larger offspring. -

Defining Genetic Diversity (Within a Population)

Primer in Population Genetics Hierarchical Organization of Genetics Diversity Primer in Population Genetics Defining Genetic Diversity within Populations • Polymorphism – number of loci with > 1 allele • Number of alleles at a given locus • Heterozygosity at a given locus • Theta or θ = 4Neμ (for diploid genes) where Ne = effective population size μ = per generation mutation rate Defining Genetic Diversity Among Populations • Genetic diversity among populations occurs if there are differences in allele and genotype frequencies between those populations. • Can be measured using several different metrics, that are all based on allele frequencies in populations. – Fst and analogues – Genetic distance, e.g., Nei’s D – Sequence divergence Estimating Observed Genotype and Allele Frequencies •Suppose we genotyped 100 diploid individuals (n = 200 gene copies)…. Genotypes AA Aa aa Number 58 40 2 Genotype Frequency 0.58 0.40 0.02 # obs. for genotype Allele AA Aa aa Observed Allele Frequencies A 116 40 0 156/200 = 0.78 (p) a 0 40 4 44/200 = 0.22 (q) Estimating Expected Genotype Frequencies Mendelian Inheritance Mom Mom Dad Dad Aa Aa Aa Aa •Offspring inherit one chromosome and thus A A one allele independently A a and randomly from each parent AA Aa •Mom and dad both have genotype Aa, their offspring have Mom Dad Mom Dad Aa Aa three possible Aa Aa genotypes: a A a a AA Aa aa Aa aa Estimating Expected Genotype Frequencies •Much of population genetics involves manipulations of equations that have a base in either probability theory or combination theory. -Rule 1: If you account for all possible events, the probabilities sum to 1. -

Lecture 25 Population Genetics Until Now, We Have Been Carrying Out

Lecture 25 Population Genetics Until now, we have been carrying out genetic analysis of individuals, for the next three lectures we will consider genetics from the point of view of groups of individuals, or populations. We will treat this subject entirely from the perspective of human population studies where population genetics is used to get the type of information that would ordinarily be obtained by breeding experiments in experimental organisms. At the heart of population genetics is the concept of allele frequency Consider a human gene with two alleles: A and a The frequency of A is f(A) ; the frequency of a is f(a) Definition: p = f(A) q = f(a) p and q can be thought of as probabilities of selecting the given alleles by random sampling. For example, p for a given population of humans is the probability of finding allele A by selecting an individual from that population at random and then selecting one of their two alleles at random. Since p and q are probabilities and in this example there are only two possible alleles; p + q = 1 Correspondingly, there are three possible genotype frequencies: f(A/A) + f(A/a) + f(a/a) = 1 We usually can't get allele frequencies directly but must derive them from the frequencies of the different genotypes that are present in a population 1 p = f(A/A) + /2 f(A/a) (homozygote) (heterozygote) 1 q = f(a/a) + /2 f(A/a) Example: M and N are different blood antigens specified by alleles of the same gene. -

CHAPTER 2 Genotype Frequencies

9781405132770_4_002.qxd 1/19/09 2:22 PM Page 9 CHAPTER 2 Genotype frequencies 2.1 Mendel’s model of particulate genetics is hard for us to fully appreciate now, but Mendel’s results were truly revolutionary and served as the • Mendel’s breeding experiments. very foundation of population genetics. The lack of • Independent assortment of alleles. an accurate mechanistic model of heredity severely • Independent segregation of loci. constrained biological explanations of cause and • Some common genetic terminology. effect up to the point that Mendel’s results were “rediscovered” in the year 1900. In the nineteenth century there were several theories It is worthwhile to briefly review the experiments of heredity, including inheritance of acquired char- with pea plants that Mendel used to demonstrate acteristics and blending inheritance. Jean-Baptiste independent assortment of both alleles within a locus Lamarck is most commonly associated with the and of multiple loci, sometimes dubbed Mendel’s discredited hypothesis of inheritance of acquired first and second laws. We need to remember that characteristics (although it is important to recognize this was well before the Punnett square (named his efforts in seeking general causal explanations of after Reginald C. Punnett), which originated in about evolutionary change). He argued that individuals 1905. Therefore, the conceptual tool we would use contain “nervous fluid” and that organs or features now to predict progeny genotypes from parental (phenotypes) employed or exercised more frequently genotypes was a thing of the future. So in revisiting attract more nervous fluid, causing the trait to Mendel’s experiments we will not use the Punnett become more developed in offspring. -

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Allele Frequencies and Genotype Frequencies How do allele frequencies relate to genotype frequencies in a population? If we have genotype frequencies, we can easily get allele frequencies. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Example Cystic Fibrosis is caused by a recessive allele. The locus for the allele is in region 7q31. Of 10,000 Caucasian births, 5 were found to have Cystic Fibrosis and 442 were found to be heterozygous carriers of the mutation that causes the disease. Denote the Cystic Fibrosis allele with cf and the normal allele with N. Based on this sample, how can we estimate the allele frequencies in the population? We can estimate the genotype frequencies in the population based on this sample 5 10000 are cf , cf 442 10000 are N, cf 9553 10000 are N, N Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Example So we use 0.0005, 0.0442, and 0.9553 as our estimates of the genotype frequencies in the population. The only assumption we have used is that the sample is a random sample. Starting with these genotype frequencies, we can estimate the allele frequencies without making any further assumptions: Out of 20,000 alleles in the sample 442+10 20000 = :0226 are cf 442+10 1 − 20000 = :9774 are N Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium In contrast, going from allele frequencies to genotype frequencies requires more assumptions. HWE Model Assumptions infinite population discrete generations random mating no selection no migration in or out of population no mutation equal initial genotype frequencies -

Résumé Abstract

RÉSUMÉ ABSTRACT Effets de la reproduction partiellement asexuée sur la dyna- Effects of partial asexuality on the dynamics of genotype frequen- mique des fréquences génotypiques en populations majori- cies in dominantly diploid populations tairement diploïdes Reproductive systems determine how genetic material is passed Les systèmes reproducteurs déterminent comment le matériel from one generation to the next, making them an important fac- génétique est transmis d’une génération à la suivante […]. Les tor for evolution. Organisms that combine sexual and asexual/ espèces qui combinent de la reproduction sexuée et asexuée/clo- clonal reproduction are very widespread [… yet] the effects of nale sont très répandues [… mais] l’effet de leur système repro- their reproductive system on their evolution are still controversial ducteur sur leur évolution reste énigmatique et discuté. and poorly understood. L’objectif de cette thèse est de modéliser la dynamique des fré- The aim of this thesis was to model the dynamics of genotype quences génotypiques d’une population avec une combinaison frequencies under combined sexual/clonal reproduction in domi- de reproduction sexuée et/ou clonale dans des cycles de vie prin- nantly diploid life cycles [. … A] state and time discrete Markov cipalement diploïdes [. … Un] modèle du type chaine de MarKov chain model served as the mathematical basis to describe [their] avec temps et états discrets sert de base mathématique pour changes […] through time. décrire [leurs] changements […] au cours du temps. The results demonstrate that partial clonality may indeed change Les résultats montrent que la reproduction partiellement asexuée the dynamics of genomic diversity compared to either exclusively peut en effet modifi er la dynamique de la diversité génomique sexual or exclusively clonal populations. -

Mendelian Population Genetics

Mendelian Population Genetics • Evolution: change in allele frequencies within a population over time A mouse is a vehicle for mouse gene replication Mice with Aa genotypes IF no mutation…Gametes IF random mating Zygotes Sum = 1 Then zygotes grow up to be adults IF no survival selection, and IF no biased migration, and IF no biased random death THEN you get these adult genotypes, which produce gametes…… Adults produce gametes IF no mutation…. Those are the same allele frequencies we started with!! A = 0.6 a = 0.4 There was no evolutionary change….IF • No mutation • Random mating • No biased migration • No biased selected mortality (selection) • No biased random mortality (drift) The general case Developed by Hardy 1908 Mind your p’s and q’s • If p = frequency of A1 allele • And q = frequency of A2 allele • And if there are only two alleles in the population at this locus • Then p + q = 1 – Alternatively q = 1- p Randomly combining gametes in the general case • Sperm are A1 with probability p • Eggs are A1 with probability p • So A1A1 zygotes are produced with probability of p X p = p2 And so on…. • A1A1 genotype has frequency of p2 • A1A2 genotype has frequency of pq • A2A1 genotype has frequency of pq • A2A2 genotype has frequency of q2 • But A1A2 is the same as A2A1 = 2 pq • Frequencies must add to 1 p2 + 2pq + q2 = 1 Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium • If a simple set of assumptions holds, then the allele frequencies in a population will not change • If we symbolize allele frequencies as p and q, then genotype frequencies are p2, 2pq, and q2 What are those simple assumptions? • No selection: genotypes survive at equal rates (i.e.