Sermon, Advent 2 Charles De Foucauld: Faith in Silence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Jesus Caritas Fraternities in the United States: the Early History 1963 – 1973

PO BOX 763 • Franklin Park, IL 60131 • [P] 260-786-JESU (5378) Website: www.JesusCaritasUSA.org • [E] [email protected] THE JESUS CARITAS FRATERNITIES IN THE UNITED STATES: THE EARLY HISTORY 1963 – 1973 by Father Juan Romero INTRODUCTION At the national retreat for members of the Jesus Caritas Fraternity of priests, held at St. John’s Seminary in Camarillo, California in July 2010, Father Jerry Devore of Bridgeport, Connecticut asked me, in the name of the National Council, to write an early history of Jesus Caritas in the United States. (For that retreat, almost fifty priests from all over the United States had gathered for a week within the Month of Nazareth, in which a smaller number of priests were participating for the full month.) This mini-history is to complement A New Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Msgr. Bryan Karvelis of Brooklyn, New York (RIP), and the American Experience of Jesus Caritas Fraternities by Father Dan Danielson of Oakland, California. It proposes to record the beginnings of the Jesus Caritas Fraternities in the USA over its first decade of existence from 1963 to 1973, and it will mark the fifth anniversary of the beatification of the one who inspired them, Little Brother Blessed Charles de Foucault. It purports to be an “acts of the apostles” of some of the Jesus Caritas Fraternity prophets and apostles in the USA, a collective living memory of this little- known dynamic dimension of the Church in the United States. It is not an evaluation of the Fraternity, much less a road map for its future growth and development. -

Saints and Blessed People

Saints and Blessed People Catalog Number Title Author B Augustine Tolton Father Tolton : From Slave to Priest Hemesath, Caroline B Barat K559 Madeleine Sophie Barat : A Life Kilroy, Phil B Barbarigo, Cardinal Mark Ant Cardinal Mark Anthony Barbarigo Rocca, Mafaldina B Benedict XVI, Pope Pope Benedict XVI , A Biography Allen, John B Benedict XVI, Pope My Brother the Pope Ratzinger, Georg B Brown It is I Who Have Chosen You Brown, Judie B Brown Not My Will But Thine : An Autobiography Brown, Judie B Buckley Nearer, My God : An Autobiography of Faith Buckley Jr., William F. B Calloway C163 No Turning Back, A Witness to Mercy Calloway, Donald B Casey O233 Story of Solanus Casey Odell, Catherine B Chesterton G. K. C5258 G. K. Chesterton : Orthodoxy Chesterton, G. K. B Connelly W122 Case of Cornelia Connelly, The Wadham, Juliana B Cony M3373 Under Angel's Wings Maria Antonia, Sr. B Cooke G8744 Cooke, Terence Cardinal : Thy Will Be Done Groeschel, Benedict & Weber, B Day C6938 Dorothy Day : A Radical Devotion Coles, Robert B Day D2736 Long Loneliness, The Day, Dorothy B de Foucauld A6297 Charles de Foucauld (Charles of Jesus) Antier, Jean‐Jacques B de Oliveira M4297 Crusader of the 20th Century, The : Plinio Correa de Oliveira Mattei, Riberto B Doherty Tumbleweed : A Biography Doherty, Eddie B Dolores Hart Ear of the Heart :An Actress' Journey from Hollywood to Holy Hart, Mother Dolores B Fr. Peter Rookey P Father Peter Rookey : Man of Miracles Parsons, Heather B Fr.Peyton A756 Man of Faith, A : Fr. Patrick Peyton Arnold, Jeanne Gosselin B Francis F7938 Francis : Family Man Suffers Passion of Jesus Fox, Fr. -

I Worry Until Midnight and from Then on I Let God Worry

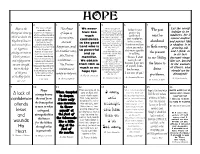

HOPE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The virtue of hope Hope is the The object We never The virtue of Let the world responds to the hope is so pleasing Today in your The past aspiration to happiness have too indulge in its theological virtue by of hope is, to God that He prayer you which God has placed in much has declared that confirmed must be madness, for it which we desire the the heart of every man; He feels delight in cannot endure it takes up the hopes in one way, confidence those who trust your resolution kingdom of heaven that inspire men's in Him: “The Lord to be a saint. abandoned and passes like eternal in the good taketh pleasure in activities and purifies I understand you a shadow. It is and eternal life as Lord who is them that hope them so as to order them happiness, and, in His Mercy” when you make to God's mercy, growing old, our happiness, to the Kingdom of so powerful (Ps. 46:11). this more specific heaven; it keeps man in another way, And He promises and I think, is placing our trust in from discouragement; and so victory over his by adding, the present in its last Christ's promises it sustains him during the Divine merciful. enemies, “I know I shall times of abandonment; perseverance in to our fidelity, decrepit stage. grace, and succeed, not and relying not on it opens up his heart in assistance . We obtain eternal glory to But we, buried expectation of eternal from Him as the man who because I am sure the future to in the wounds our own strength, beatitude. -

Inte Rna Tio Nal Bul Letin

INTERNATIONAL BULLETIN OF THE LAY FRATERNITY CHARLES DE FOUCAULD Nº 89- Nazareth- Back to the Roots June 2013 News from our Association Bread of Life « Nazareth » Meeting at with our Pope Viviers Francis Summary Editorial 3 Only God Can – Father Guy Gilbert 4 Nazareth – Claudio and Sylvana Chiaruttini 5 The God of Jesus Christ – Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger 13 An inspiring new reading with a poetic approach 14 Fraternities News 15 -Africa 15 -America 28 -Asia 33 -Europe 34 -Arab World 36 Association Meeting at Viviers: April 1st-7th 42 -How CDF has read and meditated the Bible 42 - The prayer of the Christians in the land of Islam A Testimony from Algeria 44 Practical Information 47 An inspiring new reading with a poetic approach It’s not Easy 48 Editorial Dear lay brothers and sisters throughout the whole world, We hope that you are all well. This 89th edition of the Bulletin is dedicated to our life of Nazareth, a return to the roots. Nazareth? What is that? Nazareth is a city situated in northern Israel, in Galilee. But it is also the place where Jesus Christ spent his childhood. His whole life was hidden and is not described by the evangelists. Nazareth just had to attract Brother Charles with its simplicity and it was a changing point in his life. As a consequence, the lives of many people have changed. In this 89th edition of the International Bulletin, we share with you some thoughts about Nazareth and particularly everyone`s personal Nazareth. We share the bread of life with our new pope Francis who never stops inviting us to follow Jesus Christ and to be witnesses of his Love. -

Legacy of a Spiritual Master Who Loved the Desert Eightieth Anniversary of the Death of Charles De-Foucauld

Legacy of a spiritual master who loved the desert Eightieth Anniversary of the Death of Charles De-Foucauld On 1 December 1996, in hundreds of places all over the world, Charles de Foucauld's followers gathered for the 80th anniversary of his death; they did so in their own way, discreetly; they have no distinctive feature, they have blended with the peoples to whom they wish to belong, the anonymous crowd of the poor, the rejected and those "far from God", as de Foucauld used to say the marginalized, or more simply, the common people who lead ordinary lives; they shun the spectacular: they want above all "to belong to the community", as Jesus of Nazareth did in his so- called hidden life. Since they do not seek great publicity but rather avoid it—to be consistent with their vocation— newspapers and magazines say little about Charles de Foucauld's spiritual heritage. It should also be said that speaking of this legacy raises a further difficulty: in the cause for his beatification, Fr de Foucauld is rightly not considered a "founder" of congregations. Although he scattered to the four winds "rules", "directives" and "counsels", and indicated ways of living the religious or lay life according to Nazareth, in his lifetime he founded no institutions. And his followers are as varied as the members of the Church: priests, men and women religious, lay people, found in very different Church structures, but in their real differences they are all recognizable for the same affinity. The principal leaders of the groups assembled in associations, secular institutes and religious congregations which constitute the "spiritual family of Charles de Foucauld" meet every year in Rome or some other part of the world (most recently Haiti) for a week of information and review; in 1996, there were 18 officially approved groups. -

Saint Joseph Another As Christ Loves Us!

PARISH MISSION STATEMENT We, the Catholic Community of St. Joseph, The Catholic Community of are committed to follow Jesus Christ. Through the guidance of the Holy Spirit, we strive to be good stewards in our lives. We pray for peace, forgiveness, and for one Saint Joseph another as Christ loves us! PARISH OFFICE HOURS Monday–Friday 9:00 am to 1:00 pm Evening Hours by Appointment Parish Address: 16 East Somerset Street Raritan, NJ 08869-2102 PARISH OFFICE TELEPHONE (908) 725-0163 x10 FAX (908) 725-2333 PARISH WEBSITE MASS SCHEDULE Saturday Vigil Mass: 4:00 pm Sunday: 8:00 am & 10:30 am Monday through Friday: 8:00 am Holy Days of Obligation 7:30 pm Vigil (Evening before) and 8:00 am on the Holyday. SACRAMENT OF RECONCILIATION Saturday: 3:00–3:30 pm or anytime by appointment R.C.I.A Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults Robert Paulishak, Coordinator Religious Formation/Catechesis Parish Sacramental Preparation Grades 1 through 8 Sundays: 9:15 am – 10:15 am For more information, call the Parish Office. REV. KENNETH R. KOLIBAS PASTOR Chaplain In Residence R.W.J.B. HOSPITAL AT SOMERSET REV. LAZARO PEREZ Director of Sacred Music David Shirley Parish Trustees Irene Amitrani, James Piccolo Parish Office Manager and Bulletin Editor-Webmaster James Piccolo Our Church is open from 7:30 am to 1:00 pm Please send articles to: each weekday for quiet time and prayer . E-Mail: [email protected] Please make a habit for daily prayer before the Lord! Page 2 Saint Joseph Church, Raritan – Sunday, January 21, 2018 Baby Bottle Boomerang! Saints of the Week Please pick up your baby bottle this weekend and fill with your loose change. -

A Parish Family of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston Parish Clergy Our Mission Office Hours

A Parish Family of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston Parish Clergy Office hours: Stay connected: Our Mission Are you new? Welcome! Letter from our Pastor Dear Friends in Christ, God writes straight with crooked lines is a Portuguese proverb that scholars debate has its origin in St Augustine. The lives of the saints bear out this spiritual reality of conversion, but Catholic history also attests to the existence of nu- merous personalities who might never end up canonized but for whom this is nonetheless true. Louis Massignon (1883-1962) was a French archeologist and linguist who lived in the Middle East looking for adven- ture. Raised by an agnostic father and a devout mother, he gave little thought to the faith until he had a mystical ex- perience of the divine presence that caused him to depart from his male lover. The suicide of that young man brought Massignon to a deep study of the figure of Al-Hallaj, an Islamic mystic who was murdered because of his con- tention that man could have union with God by love. Massignon was a scholar of the Arabic language and the Muslim religion, but deepened his Catholic faith. He married a young woman and was then given a dispensation to be or- dained as a priest in the Melkite Rite, for Arabic-speaking Byzantine Catholics. He later described a mystical experience as the Visitation of a Stranger: “No name remained in my memory (not even my own) that could have been shouted at Him to free me from His scheme and let me escape His trap. -

“Brother Charles De Foucauld” Lay Fraternity

“BROTHER CHARLES DE FOUCAULD” LAY FRATERNITY « THE LITTLE GUIDE » a practical guide to fraternity living and spirituality PAPAL MESSAGE DURING THE BEATIFICATION OF BROTHER CHARLES DE FOUCAULD NOVEMBER 13TH 2005 ST. PETER´S BASILICA, ROME His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI: «Let us give thanks for the testimony of Charles de Foucauld. Through his contemplative and hidden life at Nazareth, having discovered the truth about the humanity of Jesus, he invites us to contemplate the mystery of the Incarnation. There he learned much about the Lord whom he wished to follow in humility and poverty. He discovered that Jesus, having come to us to join in our humanity, invites us to universal fraternity which he would later live in the Sahara with a love of which Christ was the example. As a priest, he put the Eucharist and the Gospel, the twin tables of Bread and the Word, the source of Christian life and mission, at the center of his life. » Extract from Homily of Card. José Saraiva Martins: «Charles de Foucauld had a renowned influence on spirituality in the XX century and, at the beginning of the Third Millennium, continues to be a fruitful reference and invitation to a style of life radically evangelical not only for those of the different, numerous and diversified groups who make up his Spiritual Family. To receive the Gospel with simplicity, to evangelize without wanting to impose oneself, to witness to Jesus through respect for other religious experiences, to affirm the primacy of charity lived in the fraternity are only some of the most important aspects of a precious heritage which encourages us to act and behave so that our own life may be like that of Blessed Charles in « crying out the Gospel from the rooftop, crying out that we are of Jesus.” 2 Table of Contents Pages Preface ………………………………………… 5 Chapters 1. -

'Standardized Chapel Library Project' Lists

Standardized Library Resources: Baha’i Print Media: 1) The Hidden Words by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 193184707X; ISBN-13: 978-1931847070) Baha’i Publishing (November 2002) A slim book of short verses, originally written in Arabic and Persian, which reflect the “inner essence” of the religious teachings of all the Prophets of God. 2) Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847223; ISBN-13: 978-1931847223) Baha’i Publishing (December 2005) Selected passages representing important themes in Baha’u’llah’s writings, such as spiritual evolution, justice, peace, harmony between races and peoples of the world, and the transformation of the individual and society. 3) Some Answered Questions by Abdul-Baham, Laura Clifford Barney and Leslie A. Loveless (ISBN-10: 0877431906; ISBN-13 978-0877431909) Baha’i Publishing, (June 1984) A popular collection of informal “table talks” which address a wide range of spiritual, philosophical, and social questions. 4) The Kitab-i-Iqan Book of Certitude by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847088; ISBN-13: 978:1931847087) Baha’i Publishing (May 2003) Baha’u’llah explains the underlying unity of the world’s religions and the revelations humankind have received from the Prophets of God. 5) God Speaks Again by Kenneth E. Bowers (ISBN-10: 1931847126; ISBN-13: 978- 1931847124) Baha’i Publishing (March 2004) Chronicles the struggles of Baha’u’llah, his voluminous teachings and Baha’u’llah’s legacy which include his teachings for the Baha’i faith. 6) God Passes By by Shoghi Effendi (ISBN-10: 0877430209; ISBN-13: 978-0877430209) Baha’i Publishing (June 1974) A history of the first 100 years of the Baha’i faith, 1844-1944 written by its appointed guardian. -

A Study of the Origins, Development and Contemporary Manifestations of Christian Retreats

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository A STUDY OF THE ORIGINS, DEVELOPMENT AND CONTEMPORARY MANIFESTATIONS OF CHRISTIAN RETREATS by HUGH PETER JENKINS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY in the subject CHRISTIAN SPIRITUALITY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR JL COYLE OCTOBER 2006 1 Key terms: Christian retreats; Biblical retreats; Spiritual withdrawal; Monasticism; Discernment; Ignatian spirituality; Christian devotions; Christian meditation; Divine-Human encounter; Christian prayer. 2 Summary: The dissertation is a study of the origins, development and contemporary manifestations of Christian retreats. It traces origins from the Biblical record until current retreats. Christian retreat is a period of withdrawal from usual activities to experience encounter with God through Christian prayer. Jesus’ pattern of engagement in ministry and withdrawal is a vital basis for retreat. Other Biblical descriptions of retreat are studied. There is an examination of retreat experiences in Church history with a particular focus on monasticism, as a major expression of retreat life, and Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the modern retreat movement. Varieties of subsequent retreat types in the spiritualities of different traditions from the Protestant Reformation onwards are considered. The spectrum of study includes Protestant, Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Pentecostal spiritualities. The study culminates in focusing on current Ignatian and other retreats in their many forms. This includes private devotions to lengthy periods of retreat. 3 Declaration: I declare that “A study of the origins, development and contemporary manifestations of Christian retreats” is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. -

Roman Catholic Authors, Teachers and Saints

Roman Catholic Authors, Teachers and Saints Crossing the Threshold of Hope by Pope John Paul II God is Love by Pope Benedict XVI Jesus of Nazareth: Volumes 1 and 2 by Pope Benedict XVI The Violence of Love: The Pastoral Wisdom of Archbishop Oscar Romero Translated and compiled by James Brockman, S.J. Mother Teresa: No Greater Love with an introduction by Thomas Moore Come Be My Light: the Private Writings of the Saint of Calcutta by Brian Kolodiechuk Finding Calcutta: What Mother Teresa Taught Me by Mary Poplin Love is the Measure: A Biography of Dorothy Day by Jim Forest Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion by Gregory Boyle, SJ Charles de Foucauld: Writings selected and introduced by Robert Ellsberg Aunt Edith: The Jewish Heritage of a Catholic Saint by Susanne Batzdorff The Book of my Life by St. Teresa of Avila (translated by Mirabai Starr) The Imitation of Christ by Thomas of Kempis Reaching Out by Henri J.M. Nouwen Letters to Marc about Jesus by Henri J.M. Nouwen The Genesee Diary by Henri J.M. Nouwen The Return of the Prodigal Son by Henri J.M. Nouwen The Way of the Heart by Henri J.M. Nouwen Clowning in Rome by Henri J.M. Nouwen Behold the Beauty of the Lord by Henri J.M. Nouwen The Only Necessary Thing by Henri J.M. Nouwen; compiled by Wendy Greer To Believe in Jesus by Ruth Burrows, OCD The Way of Silent Love by a Carthusian 1 Interior Prayer by a Carthusian Thirsting for Prayer by Jacques Philippe Interior Freedom by Jacques Philippe Sacred Reading by Michael Casey, OCSO Toward God by Michael Casey, OCSO Invitation -

Catalog Spring 2019

Fostering a culture of unity and dialogue Catalog Spring 2019 800-462-5980 New Releases www.newcitypress.com Best of Backlist New Releases New Resisting Throwaway Culture Climate Generation How a Consistent Life Ethic Can Unite Awakening to Our Children’s Future a Fractured People Lorna Gold Charles C. Camosy Join a mother discovering the reality of climate Learn how the consistent life ethic embraced by change and how she can protect her children Catholic teaching can help us put people at the cen- and their world. Lorna Gold’s journey brings ter by moving from policy and politics back to basic hope for effective communal action. goods and ideas held in common across divisions. Paper: 978-1-56548-676-8 $14.95 Paper: 978-1-56548-687-4 $19.95 Transfiguring Time The Donatist Controversy I Understanding Time in the Light St. Augustine of the Orthodox Tradition Translated by Maureen Tilley and Boniface Ramsey Olivier Clément - Preface by Ilia Delio, OSF Edited by Boniface Ramsey and David G. Hunter Translated by Jeremy N. Ingpen This volume contains the first new English transla- Published here for the first time in English, tions of Augustine’s writings against the Donatists Clément’s essay demonstrates the exhilarating in more than 100 years, and in the case of at effects of the Incarnation on our experience and least one writing there has never been an English understanding of time and eternity, life and death. translation until now. 2 Paper: 978-1-56548-680-5 $16.95 Hard Cover: 978-1-56548-404-7 $89.00 New Releases New The Church The Universal Brother What is it? Who is it? Charles de Foucauld Speaks to Us Today Chiara Lubich Little Sister Kathleen of Jesus What purpose does the Church serve? Chiara Charles de Foucauld’s story is that of a man of Lubich says it is called to be a catalyst for unity, inspiring faith, who threw himself into all his a mission only possible because the Church endeavors, including prayer and evangelization, draws its life from God who is Love.