AIMPE Supplementary SUBMISSION to HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recipients of Honoris Causa Degrees and of Scholarships and Awards 1999

Recipients of Honoris Causa Degrees and of Scholarships and Awards 1999 Contents HONORIS CAUSA DEGREES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE- Members of the Royal Family 1 Other Distinguished Graduates 1-9 SCHOLARSHIPS AND AWARDS- The Royal Commission of the Exhibition of 1851 Science Research Scholarships 1891-1988 10 Rhodes Scholars elected for Victoria 1904- 11 Royal Society's Rutherford Scholarship Holders 1952- 11 Aitchison Travelling Scholarship (from 1950 Aitchison-Myer) Holders 1927- 12 Sir Arthur Sims Travelling Scholarship Holders 1951- 12 Rae and Edith Bennett Travelling Scholarship Holders 1979- 13 Stella Mary Langford Scholarship Holders 1979- 13 University of Melbourne Travelling Scholarships Holders 1941-1983 14 Sir William Upjohn Medal 15 University of Melbourne Silver Medals 1966-1985 15 University of Melbourne Medals (new series) 1987 - Silver 16 Gold 16 31/12/99 RECIPIENTS OF HONORIS CAUSA DEGREES AND OF SCHOLARSHIPS AND AWARDS Honoris Causa Degrees of the University of Melbourne (Where recipients have degrees from other universities this is indicated in brackets after their names.) MEMBERS OF THE ROYAL FAMILY 1868 His Royal Highness Prince Alfred Ernest Albert, Duke of Edinburgh (Edinburgh) LLD 1901 His Royal Highness Prince George Frederick Ernest Albert, Duke of York (afterwards King George V) (Cambridge) LLD 1920 His Royal Highness Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward VIII) (Oxford) LLD 1927 His Royal Highness Prince Albert Frederick Arthur George, -

Consolidated Gold Fields in Australia the Rise and Decline of a British Mining House, 1926–1998

CONSOLIDATED GOLD FIELDS IN AUSTRALIA THE RISE AND DECLINE OF A BRITISH MINING HOUSE, 1926–1998 CONSOLIDATED GOLD FIELDS IN AUSTRALIA THE RISE AND DECLINE OF A BRITISH MINING HOUSE, 1926–1998 ROBERT PORTER Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463496 ISBN (online): 9781760463502 WorldCat (print): 1149151564 WorldCat (online): 1149151633 DOI: 10.22459/CGFA.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph John Agnew (left) at a mining operation managed by Bewick Moreing, Western Australia. Source: Herbert Hoover Presidential Library. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS List of Figures, Tables, Charts and Boxes ...................... vii Preface ................................................xiii Acknowledgements ....................................... xv Notes and Abbreviations ................................. xvii Part One: Context—Consolidated Gold Fields 1. The Consolidated Gold Fields of South Africa ...............5 2. New Horizons for a British Mining House .................15 Part Two: Early Investments in Australia 3. Western Australian Gold ..............................25 4. Broader Associations .................................57 5. Lake George and New Guinea ..........................71 Part Three: A New Force in Australian Mining 1960–1966 6. A New Approach to Australia ...........................97 7. New Men and a New Model ..........................107 8. A Range of Investments. .115 Part Four: Expansion, Consolidation and Restructuring 1966–1981 9. Move to an Australian Shareholding .....................151 10. Expansion and Consolidation 1966–1976 ................155 11. -

1976 Monash University Calendar Part 1

MARIST COLLEGE ORMANBY ROAD MONASH Jp~ UNIVERSITY C'.S.I.R.O. SCALE IN METRES 0 21i liO 71i 100 121i 150 171i 200 HAllS OF RESIDENCE 30 ANIMAL KEY TO PLAN • HOUSES •• I. University club - 2. Religious centre MARSHAll RESERVE 3. Robert Blackwood Hall ENGINEERING 4. Main library 5. Krongold child training centre 6. The Alexander Theatre 7. Rotunda 8. Biomedical library 9. Biochemistry laboratories 10. Central science block SPORTS AREA II. Senior zoology 12. First year chemistry 13. Zoology lecture theatres 14. First year biology laboratory SPORTS AREA 15. Senior chemistry 16. Western science lecture theatres UJ :Jz 17. Eastern science lecture theatres UJ > 18. First year physics < UJ 19. Senior physics 8 0 20. Hargrave Library UJ = 21. Northern science lecture theatres 22. Mathematics and computer centre 23. Engineering lecture theatres 24. 25. 26. 27. Engineering school 28. Boiler-house 29. Botany experimental area VICE-CHANCEllOR'S RESIDENCE,.,. 30. Zoology environmental laboratories EDUCATION ,, ERECTED NON-COLlEGIATE HOUSING UNDER CONSTRUCTION MANNIX COLLEGE MONASH UNIVERSITY CALENDAR 1976 Published by Monash University Wellington Road, Clayton Victoria, Australia 3168 Telephone: 541 0811 Telegrams: Monashuni Melbourne Telex: Monlib AA31729 Printed and bound by Brown Prior Anderson Pty Ltd Melbourne CONTENTS (The contents of the Calendar have been brought up to date as at 5 January 1976 with the exception of the statutes and regulations which were those in force at 13 October 1975) PREFACE 9 SIR JOHN MONASH 11 COAT OF ARMS 13 DONATIONS -

Past Ausimm Award Winners

The AusIMM Awards Recipients Contents The Institute Medal............................................................................................................................... 2 President’s Award .............................................................................................................................. 10 Honorary Fellowships......................................................................................................................... 16 Beryl Jacka Award ........................................................................................................................... 234 Mineral Industry Operating Technique Award (MIOTA) ..................................................................... 29 Renamed Mineral Industry Technique Award (MITA) ........................................................................ 33 OH&S Award (Introduced in 2001) ..................................................................................................... 35 Professional Excellence Awards ........................................................................................................ 38 G B O’Malley Medal ........................................................................................................................... 41 Branch Service Award........................................................................................................................ 40 AusIMM Service Award ..................................................................................................................... -

Just Passing Through

1 JUST PASSING THROUGH 1. INTRODUCTION I was born in Estonia. Leaving there as a teenager ahead of the second Soviet occupation of that country in September 1944, I became a refugee in Germany. Immigrating to Australia in 1949 and becoming a citizen, most of my working life was then spent in the minerals industry until retirement in 1999. Some of my friends, no doubt conscious of the relentless passage of time, have urged me to record my recollections. They have been mostly too gentle to add “before it is too late”. I had been doing this in considerable detail, including my family history going back just over 300 years and the events in Western Mining Corporation during the 25 years I was the Chairman. The complete record is too detailed to be of general interest and I have therefore prepared this selection of topics which, while omitting many episodes and only just touching on others, deals with many of the happenings in my life and includes reflections on a number of issues. It is not for publication, but a private document for a limited circle of family and friends. The initial manuscript was concluded in September 2005. Amended and updated on several occasions, it was finalised in January 2008. When considering past events, we must remember that the world then was different from today‟s. Even in my lifetime both the physical conditions of life – travel, communications, living standards generally – and people‟s attitudes, perceptions and values have gone through a great change. Going further back the changes are greater still. -

1965 Monash University Calendar Part 1

CALENDAR OF MONASH UNIVERSITY 1965 WELLINGTON ROAD, CLAYTON, VICTORIA AUSTRALIA PUBLISHED BY MONASH UNIVERSITY Printed and bound by Wilke & Co. Ltd., Melbourne CONTENTS (Except where otherwise stated the contents of the Calendar have been brought up to date as at January 29, 1965) PREFACE 9 COAT OF ARMS 11 PRINCIPAL DATES FOR 1965 12 OFFICERS AND STAFF OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY 24 MEMBERS OF COUNCIL 24 STANDING COMMITTEES OF COUNCIL 26 THE PROFESSORIAL BOARD 28 STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE PROFESSORIAL BOARD 29 THE FACULTIES 30 TEACHING AND RESEARCH STAFF 36 ADMINISTRATIVE AND OTHER STAFF 59 CLINICAL INSTRUCTORS OF THE TEACHING HOSPITALS 62 THE MONASH UNIVERSITY ACT 1958 (As amended to January 29, 1965) 70 STATUTES OF THE UNIVERSITY CHAPTER 1 - GENERAL 1.1 Interpretation 89 1.2 Meetings 91 1.3 University Holidays 91 CHAPTER 2 - GOVERNING BODIES, COMMITTEES, AND UNIVERSITY ORGANIZATIONS 2.1 The Council 91 2.2 The Professorial Board 92 2.3 The Faculties 94 2.4 The Clinical Schools 98 2.6 The Discipline Committee 99 2.8 Students' Loan Fund 99 CHAPTER 3 - OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY 3.1 The Chancellor and the Deputy Chancellor 100 3.2 The Vice-Chancellor 102 3.3 The Deans of Faculties 103 3.4.1 The Professors 105 3.4.2 Visiting Professors 107 3.4.3 Emeritus Professors 107 5 6 MONASH UNIVERSITY CALENDAR 3.5 The Registrar 107 3.6 Staff Superannuation Scheme 108 CHAPTER 4 - DISCIPLINE 4.1 General Provisions 118 CHAPTER 5 5.1 The Victorian Universities and Schools Examinations Board 120 CHAPTER 6- CANDIDATURE FOR AND ADMISSION TO DEGREES AND GRANTING -

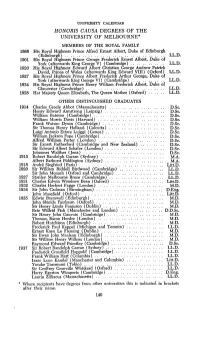

Honoris Causa Degrees of the University of Melrourne0

UNIVERSITY CALENDAR HONORIS CAUSA DEGREES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MELROURNE0 MEMBERS OF THE ROYAL FAMILY 1868 His Royal Highness Prince Alfred Emest Albert, Duke of Edinburgh (Edinburgh) LL..L). 1901 His Royal Highness Prince George Frederick Emest Albert. Duke of York (afterwards King George V) (Cambridge) LL.D. 1920 His Royal Highness Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward VIII) (Oxford) LL.D. 1027 His Royal Highness Prince Albert Frederick Arthur George, Duke of York (afterwards King George VI) (Cambridge) LL.D. 1934 His Royal Highness Prince Henry William Frederick Albert, Duke of Gloucester (Cambridge) LL.D. 1958 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother (Oxford) LL.D. OTHER DISTINGUISHED GRADUATES 1914 Charles Greely Abbot (Massachusetts) D.St Henry Edward Armstrong (Leipzig) D.S& William Bateson (Cambridge) D-Sc, William Morris Davis (Harvard) D.Sc Frank Watson Dyson (Cambridge) D.Sc. Sir Thomas Henry Holland (Calcutta) D.Sc, Luigi Antonio Ettore Luiggl (Genoa) D.Sc. William Jackson Pope (Cambridge) D-Sc. Alfred William Porter (London) D.S& Sir Emest Rutherford (Cambridge and New Zealand) D.Sc. Sir Edward Albert Schafer (London) D.Sc. Johannes Wolther (Jena) D.Sc. 1915 Robert Randolph Garran (Sydney) M.A- Albert Bathurst Fiddington (Sydney) M.A. 1918 Andre Siegfried (Paris) Utt.D. 1920 Sir William Rlddell BIrdwood (Cambridge) LLJ>. Sir John Monash (Oxford and Cambridge) LL.D. 1927 Stanley Melboume Bruce (Cambridge) LL.D. 1931 Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean (Oxford) LittJ>. 1932 Charles Herbert Fagge (London) M.D. 1934 Sir John Cadman (Birmingham) D.Eng. John Masefield (Oxford) Utl-D. -

Honoris Causa Degrees of The

UNIVERSITY CALENDAR HONORIS CAUSA DEGREES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE0 MEMBERS OF THE ROYAL FAMILY 1868 His Royal Highness Prince Alfred Emest Albert, Duke of Edinburgh (Edinburgh) LL.D. 1901 His Royal Highness Prince George Frederick Emest Albert. Duke of York (afterwards King George V) (Cambridge) LL.D. 1920 His Royal Highness Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David, Prince of Wales (afterwards King Edward VIII) (Oxford) LL.D. 1927 His Royal Highness Prince Albert Frederick Arthur George, Duke of York (afterwards King George VI) (Cambridge) LL.D. 1934 His Royal Highness Prince Henry WilUam Frederick Albert, Duke of Gloucester (Cambridge) LL.D. 1958 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother (Oxford) LL.D. OTHER DISTINGUISHED GRADUATES 1914 Charles Greely Abbot (Massachusetts) D.Sc. Henry Edward Armstrong (Leipzig) D.Sc. William Bateson (Cambridge) D.Sc. WUliam Morris Davis (Harvard) D.Sc. Frank Watson Dyson (Cambridge) D.Sc. Sir Thomas Henry Holland (Calcutta) D.Sc. Luigi Antonio Ettore Luiggi (Genoa) D.Sc. WUliam Jackson Pope (Cambridge) D.Sc. Alfred WilUam Porter (London) D.Sc. Sir Ernest Rutherford (Cambridge and New Zealand) D.Sc. Sir Edward Albert Schafer (London) D.Sc. Johannes Walther (Jena) D.Sc. 1915 Robert Randolph Garran (Sydney) M.A. Albert Bathurst Piddington (Sydney) M.A. 1918 Andre Siegfried (Paris) Litt.D. 1920 Sir WiUiam Riddell Birdwood (Cambridge) LL.D. Sir John Monash (Oxford and Cambridge) LL.D. 1927 Stanley Melboume Bruce (Cambridge) LL.D. 1931 Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean (Oxford) Litt.D. 1932 Charles Herbert Fagge (London) M.D. 1934 Sir John Cadman (Birmingham) D.Eng. John Masefield (Oxford) Litt.D. -

1969 Monash University Calendar Part 1

MONASH UNIVERSITY MARSHALL RESERVE I. Sports buildiDp 2. Gnat Hall 3. Main b"bruy 4. 1bo Aleundlr Tbeatre s. RotUnda 6. Jlio.medic:allibrary 7. Ceabll acicncc block 8. Senior IOOloJy 9. .1.oohW Jecalre the8ares 10. Fmt ,_-biok1111aboRm(y 11. Senior dlendlby 12. s.lotpbJiic:l ud ~ SPORTS AREA lec:tule theatre~ 13. Seuiot playsic:a 14. fint,... c:llemistry IS. ........Pint,_ a:ie8ce 16. Mlll!aDMiaa ... ftnt,...JQ~ic:S 17. EaaiDeerinllecture dlatrcl II, 19, 20, 21, 22. ~school 23.~ UNDER CONSTRUCTION TO BE ERECTED DUIUNG 1967-69 TRIENNIUM CALENDAR OF MONASH UNIVERSITY 1969 VOLUME ONE WELLINGTON ROAD CLAYTON VICTORIA AUSTRALIA 3168 PUBLISHED BY MONASH UNIVERSITY Printed and bound by The Specialty Press Limited, Melbourne CONTENTS OF VOLUME ONE (Except where otherwise stated the contents of the Calendar have been brought up to date as at 3 January 1969) PREFACE 9 SIR JOHN MONASH 11 COAT OF ARMS 13 DONATIONS AND BEQUESTS 14 PRINCIPAL DATES FOR 1969 15 OFFICERS AND STAFF OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY 27 MEMBERS OF COUNCIL 27 STANDING COMMITEES OF COUNCIL 30 THE PROFESSORIAL BOARD 32 STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE PROFESSORIAL BOARD 33 OTHER STANDING COMMITTEES 36 THE FACULTIES 36 THE UNION BOARD 47 REPRESENTATIVES ON OUTSIDE BODIES 48 TEACHING AND RESEARCH STAFF 50 LIBRARY STAFF 86 ADMINISTRATIVE AND OTHER STAFF 88 CLINICAL INSTRUCTORS OF THE TEACHING HOSPITALS 94 FORMER OFFICERS 103 AFFILIATED INSTITUTIONS 105 THE MONASH UNIVERSITY ACT 1958 (As amended to 3 January 1969) 106 STATUTES OF THE UNIVERSITY CHAPTER 1 - GENERAL 1.1 Interpretation 125 1.2 -

1972 Monash University Calendar Part 1

MONASH UNIVERSITY : .... SPORTS AREA CALENDAR OF MONASH UNIVERSITY 1972 WELLINGTON ROAD CLAYTON VICTORIA AUSTRALIA 3168 PUBLISHED BY MONASH UNIVERSITY Printed and bound by Brown Prior Anderson Proprietary Limited, Melbourne CONTENTS (Except where otherwise stated the contents of the Calendar have been brought up to date as at 1 October 1971) PREFACE 9 SIR JOHN MONASH 11 COAT OF ARMS 13 DONATIONS AND BEQUESTS 14 PRINCIPAL DATES FOR 1972 15 OFFICERS AND STAFF OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY 27 MEMBERS OF COUNCIL 27 STANDING COMMITTEES OF COUNCIL 30 THE PROFESSORIAL BOARD 32 STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE PROFESSORIAL BOARD 33 OTHER STANDING COMMITTEES 38 THE UNION BOARD 38 THE FACULTIES 38 REPRESENTATIVES ON OUTSIDE BODIES 53 TEACHING AND RESEARCH STAFF 55 LIBRARY STAFF 97 ADMINISTRATIVE AND OTHER STAFF 99 CLINICAL INSTRUCTORS OF THE TEACHING HOSPITALS 106 FORMER OFFICERS 117 AFFILIATED INSTITUTIONS 119 THE MONASH UNIVERSITY ACT 1958 (As amended to 1 October 1971) 120 STATUTES OF THE UNIVERSITY 'CHAPTER I-GENERAL 1.1 Interpretation 139 1.2 Meetings 141 1.3 University Holidays 142 .CHAPTER 2-GOVERNING BODIES, COMMITTEES, AND UNIVERSITY ORGANIZATIONS 2.1 The Council 142 2.2 The Professorial Board 143 2.3 The Faculties 144 5 6 MONASH UNIVERSITY CALENDAR 2.4 The University Teaching Hospitals 148 2.5 Committees 149 2.6 The Discipline Committee 150 2.7 The Union 151 2.8 Students' Loan Fund 153 2.9 The Committee of Deans 153 CHAPTER 3--oFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY 3.1 The Chancellor and the Deputy Chancellor 154 3.2.1 The Vice-Chancellor 157 3.2.2 Pro-Vice-Chancellors -

Laver Family

LAVER FAMILY Jonas Laver, a farmer from Somerset, England arrived in Melbourne on board the ‘Maitland’ in 1846, and married Mary Ann Fry in 1854. They had seven sons, all of them helping to make up an unusually talented family in the medical, sporting and musical fields. Their third son, Charles William Laver, was born in Castlemaine, Victoria on the 26th June 1863, and moved to Western Australia in the 1880s, where he became a drover before returning to Victoria to attend the Medical School at the University of Melbourne. Marrying Edith Beatrice Attewell in 1904, he returned to Western Australia as a country doctor, where he was known as ‘Mr the Doctor’ by the Aborigines. The family lived at Laverton, Wellington Mills, Kanowna, Menzies and Midland Junction before moving to Kalgoorlie in May 1920,. Charles died in 1937, being survived by his wife and six children. Following Dr. Laver’s death, Mrs Laver and her daughters, Sheila and Elizabeth settled in East Melbourne. Sheila and Elizabeth returned to Kalgoorlie in 1979, they bought a house in Collins Street the following year, where they spent their retirement years. (see fuller notes on Sheila Laver, at 6848A/1135) Collections received 849A: March 1960 2716A: 19 April 1978 5355A: 6 July 1979 6848A: PRIVATE ARCHIVES MANUSCRIPT NOTE (MN 1782; ACC 849A, 2716A, 5355A, 6848A) SUMMARY OF CLASSES ALBUMS/SCRAPBOOKS MEMBERSHIP CARDS/CERTIFICATES ARTICLES NEWSPAPER CUTTINGS BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES NOTES BUSINESS CARDS OBITUARIES (Included with EULOGIES, etc.) CARDS PAINTINGS CARDS, Sympathy (Included with EULOGIES, etc.) PHOTOGRAPH ALBUMS Listed under Albums CERTIFICATES PHOTOGRAPHS, Loose (Pictorial BA1966/1-154) CIRCULARS POEMS EULOGIES/OBITUARIES/SYMPATHY CARDS, PROGRAMMES LETTERS & TELEGRAMS RECEIPTS/DONATIONS INFORMATION SHEETS REFERENCES INVITATIONS REPORTS LEGAL PAPERS SPEECHES LETTERS TELEGRAMS LETTERS, Sympathy (Included with EULOGIES, TELEGRAMS – Sympathy telegrams are included etc) with EULOGIES, OBITUARIES, etc.) LICENCES WILLS (Included with LEGAL PAPERS) MN 1782 Page 1 of 69 Copyright SLWA ©2010 Acc. -

Hamersley Iron and the Mount Newman Company

Journal of Australasian Mining History, Vol. 11, October 2013 The Establishment of Iron Ore Giants: Hamersley Iron and the Mount Newman Mining Company, 1961–1969 By DAVID LEE Director of the Historical Publications and Information Section, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, and Adjunct Professor in History, Deakin University. etween 1938 and 1960 the Australian Government prohibited export of iron ore because of its belief that Australia’s limited accessible reserves of iron ore had B to be preserved for the Broken Hill Proprietary Company (BHP) and the Australian steel industry. After the Commonwealth hesitantly relaxed the embargo in November 1960 to encourage exploration, independent Australian prospectors Lang Hancock and Stan Hilditch revealed that they had already discovered huge deposits of iron ore in the Pilbara in Western Australia. This article explores the development of companies to mine these deposits during a period when the Australian Government, although lifting the iron embargo, attempted to regulate the prices that the companies negotiated with their buyers. The success of the two largest iron ore companies, Hamersley Iron and the Mount Newman Company, was based on their signing long- term contracts with the Japanese steel industry, which permitted them to obtain the considerable foreign capital needed to finance the infrastructure for mines located hundreds of kilometres from the coast. While that was the case and while Hancock and Hilditch were forced to approach overseas miners to initiate the development of mining companies, Australian management of both operations was also an essential part of the success of both ventures. End of the embargo, and iron ore discoveries of Lang Hancock and Stan Hilditch The embargo of iron ore from 1938 to 1960 was a period of steady growth in the Australian steel industry and of BHP, so much so that BHP’s management became strongly wedded to the maintenance of the export ban well after the Pacific War had ended.