RECLAMATION and the POLITICS of CHANGE: Rights Settlement Act of 1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newlands Project

MP Region Public Affairs, 916-978-5100, http://www.usbr.gov/mp, February 2016 Mid-Pacific Region, Newlands Project History The Newlands Project was one of the first Reclamation projects. It provides irrigation water from the Truckee and Carson Rivers for about 57,000 acres of cropland in the Lahontan Valley near Fallon and bench lands near Fernley in western Nevada. In addition, water from about 6,000 acres of project land has been transferred to the Lahontan Valley Wetlands near Fallon. Lake Tahoe Dam, a small dam at the outlet of Lake Tahoe, the source of the Truckee Lake Tahoe Dam and Reservoir River, controls releases into the river. Downstream, the Derby Diversion Dam diverts the water into the Truckee Canal and Lahontan Dam, Reservoir, carries it to the Carson River. Other features and Power Plant include Lahontan Dam and Reservoir, Carson River Diversion Dam, and Old Lahontan Dam and Reservoir on the Carson Lahontan Power Plant. The Truckee-Carson River store the natural flow of the Carson project (renamed the Newlands Project) was River along with water diverted from the authorized by the Secretary of the Interior Truckee River. The dam, completed in 1915, on March 14, 1903. Principal features is a zoned earthfill structure. The reservoir include: has a storage capacity of 289,700 acre-feet. Old Lahontan Power Plant, immediately below Lahontan Dam, has a capacity of Lake Tahoe Dam 42,000 kilowatts. The plant was completed in 1911. Lake Tahoe Dam controls the top six feet of Lake Tahoe. With the surface area of the lake, this creates a reservoir of 744,600 acre- Truckee Canal feet capacity and regulates the lake outflow into the Truckee River. -

Reallocating Water in the Truckee River Basin, Nevada and California Barbara Cosens University of Idaho College of Law, [email protected]

UIdaho Law Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law Articles Faculty Works 2003 Farmers, Fish, Tribal Power and Poker: Reallocating Water in the Truckee River Basin, Nevada and California Barbara Cosens University of Idaho College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Agriculture Law Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation 14 Hastings W.-Nw. J. Envt'l L. & Pol'y 89 (2003) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The law governing allocation of water in the western United States has changed little in over 100 years.1 Over this period, however, both our population and our understanding of the natural systems served by rivers have mushroomed. 2 To meet growing urban needs and to reverse the environmental cost extracted from natural systems, contemporary water pol- icy globally and in the West increasingly Farmers, Fish, Tribal Power focuses less on water development and and Poker: Reallocating more on improvements in management, Water in the Truckee understanding. 3 River Basin, Nevada and efficiency, and scientific California These efforts are frequently at odds with & Associate Professor, University of Idaho, By BarbaraA. Cosenss College of the Law, Former Assistant Professor, Environmental Studies Program, San Francisco State University. Mediator for the Walker River dispute. Former legal counsel, Montana Reserved Water rights Compact Commission. -

Lake Tahoe Region Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan CALIFORNIA ‐ NEVADA

Lake Tahoe Region Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan CALIFORNIA ‐ NEVADA DRAFT September 2009 Pending approval by the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force This Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan is part of a multi-stakeholder collaborative effort to minimize the deleterious effects of nuisance and invasive aquatic species in the Lake Tahoe Region. This specific product is authorized pursuant to Section 108 of Division C of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2005, Public Law 108-447 and an interagency agreement between the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the California Tahoe Conservancy. This product was prepared by: Suggested citation: USACE. 2009. Lake Tahoe Region Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan, California - Nevada. 84 pp + Appendices. Cover photo credits: Lake Tahoe shoreline, Toni Pennington (Tetra Tech, Inc.); curlyleaf pondweed, Steve Wells (PSU); Asian clams, Brant Allen (UCD); bullfrog (USGS), zebra mussels (USGS); bluegill and largemouth bass (USACE) ii i Table of Contents Acknowledgements................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................... iv Glossary.................................................................................................................................. vi Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... -

Newlands Project Frequently Asked Questions

Newlands Project Frequently Asked Questions http://www.usbr.gov/mp/lbao/ What is the Newlands Project? The Newlands Project in Nevada is one of the first Reclamation projects in the country, with construction beginning in 1903. It covers lands in the counties of Churchill, Lyon, Storey, and Washoe and provides water for about 57,000 acres of irrigated land in the Lahontan Valley near Fallon and bench lands near Fernley. Made up of two divisions, the Truckee Division and the Carson Division, the Project has features in both the Carson and Truckee River basins with the Truckee Canal allowing interbasin diversions from the Truckee River to the Carson River. The major features of the Newlands Project include Lake Tahoe Dam, Derby Diversion Dam, the Truckee Canal, Lahontan Dam, Lahontan Power Plant, Carson River Diversion Dam and canals, laterals, and drains for irrigation of approximately 57,000 acres of farmlands, wetlands and pasture. Water for the Newlands Project comes from the Carson River and supplemental water is diverted from the Truckee River into the Truckee Canal at Derby Dam for conveyance to Lahontan Reservoir for storage. The water stored in Lahontan Reservoir or conveyed by the Truckee Canal is released into the Carson River and diverted into the `V` and `T` Canals at Carson Diversion Dam. The Bureau of Reclamation has a contract with the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District to operate and maintain the Newlands Project on behalf of the Federal government. Who is the Bureau of Reclamation? The Bureau of Reclamation is a federal agency within the Department of the Interior. -

Basis for the TROA California Guidelines

Truckee River Operating Agreement Basis for the 2018 California Guidelines for Truckee River Reservoir Operations This page intentionally left blank. STATE OF CALIFORNIA Edmund G. Brown, Jr., Governor CALIFORNIA NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY John Laird, Secretary for Natural Resources Department of Water Resources Cindy Messer Karla Nemeth Kristopher A. Tjernell Chief Deputy Director Director Deputy Director Integrated Watershed Management Division of Integrated Regional Water Management Arthur Hinojosa, Chief Truckee River Operating Agreement BASIS for the 2018 CALIFORNIA GUIDELINES for TRUCKEE RIVER RESERVOIR OPERATIONS This informational document was prepared for use by the Truckee River Operating Agreement Administrator and all signatory parties to that Agreement pursuant to Public Law 101-618 and the Truckee River Operating Agreement (TROA) Preparation Team Department of Water Resources North Central Region Office, Regional Planning and Coordination Branch California – Nevada & Watershed Assessment Section Juan Escobar, P.E, Office Chief (Acting) Amardeep Singh, P.E., Branch Chief Paul Larson, P.E., Section Chief Tom Scott, P. E . , Engineer, W.R. David Willoughby, Engineer, W.R. California Department of Fish and Wildlife Laurie Hatton, Senior Environmental Scientist In coordination with: Truckee River Basin Water Group (TRBWG); Richard Anderson, Chair This page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Truckee River Operating Agreement

Revised Draft Environmental Impact Statement/ Environmental Impact Report Truckee River Operating Agreement Cultural Resources Appendix California and Nevada August 2004 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Fish and Wildlife Service Bureau of Indian Affairs State of California Department of Water Resources Cultural Resources Appendix Contents Page I. Section 1: Overview........................................................................................................... 2 A. Study Area.................................................................................................................... 2 B. Prehistoric Settlement ................................................................................................... 2 1. Pre-Archaic Period.................................................................................................. 2 2. Archaic Period........................................................................................................ 2 3. Early Archaic Period............................................................................................... 2 4. Middle Archaic Period............................................................................................ 3 5. Late Archaic Period ................................................................................................ 3 C. Ethnographic Use.......................................................................................................... 5 D. Historic Settlement..................................................................................................... -

Truckee River Geographic Response Plan

Truckee River Geographic Response Plan Truckee River Corridor Placer, Nevada, and Sierra Counties, California and Washoe, Storey, and Lyon Counties, Nevada October 2011 Prepared by: Truckee River Area Committee (TRAC) Truckee River Geographic Response Plan October 2011 Acknowledgements The Truckee River Geographic Response Plan (TRGRP) was developed through a collaborative effort between the local, state, and federal government agencies listed below. Local Government Reno Fire Department City of Reno Truckee Fire Department State Government California Department of Fish and Game, Office of Spill Prevention and Response California Emergency Management Agency Nevada Division of Environmental Protection Federal Government U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Region IX EPA’s Superfund Technical Assessment and Response Team (START), Ecology & Environment Inc. Tribal Government Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe Reno Sparks Indian Colony In addition, the following agencies provided valuable input to the TRGRP: Local Government California Public Utilities Nevada County Environmental Commission Health Nevada Division of Emergency Placer County Office of Management Emergency Services Nevada Division of Placer County Sheriff’s Office Environmental Protection Reno Fire Department Truckee Fire Department Federal Emergency Truckee Police Department Management Agency Washoe County District Health U.S. Environmental Protection Department Agency Region IX State Government Private/Public Organizations California Department of Fish -

CED-82-85 Water Diverted from Lake Tahoe Has Been Within Authorized

UNIT&&ES GENERALACCOUNT~NGOFFICE WASHINGTON, DE. 20548 May 19, 1982 COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC DEVELCPMENT DIVISION B-207402 118501 The Honorable George Miller House of Representatives Subject: Water Diverted from Lake Tahoe Has Been Within Authorized Levels (GAO/CED-82-85) Dear Mr. Miller: In your letter of January 29, 1982, and our subsequent discussions with your office , you expressed concern about the water diverted (released) from Lake Tahoe and the resulting reduction in the level of the lake. You asked us for information on the operation of the lake and, specifically, how release rates were established and whether these rates have been met or exceeded during the last 10 years. Essentially, releases fromtthe Department of the Interior's Bureau of Reclamation-controlled Lake Tahoe Dam are regulated by court decree and monitored by'a court-appointed water master. Over the last 10 years, releases have not resulted in improper reductions in the level of the lake. OBJECTIVES, SCOPE, AND METHODOLOGY The objectives of this review were to provide information on the management of Lake Tahoe water releases and to determine how release rates are established and if such releases have met or exceeded the established rates during the last 10 years. We made our review at the offices of the Federal Water Master in Reno, Nevada, and the Bureau of Reclamation's Mid-Pacific Region in Sacramento, California, and its district office in Carson City, Nevada. We interviewed the Federal Water Master and Bureau officials and reviewed records maintained at those locations. We also reviewed the various court decrees that regulate releases from Lake Tahoe and the contract between the Bureau and the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District that provides for construction cost repayment of the Lake Tahoe Dam and other features of the Newlands Project. -

TER WORDS DIVISION of WATER PLANNING T Tacking — the Binding of Mulch Fibers by Mixing Them with an Adhesive Chemical Compound During Land Restoration Projects

WATER WORDS DIVISION OF WATER PLANNING T Tacking — The binding of Mulch fibers by mixing them with an adhesive chemical compound during land Restoration projects. Tafoni — Natural cavities in rocks formed by weathering. Tahoe–Prosser Exchange Agreement [California-Nevada] — Also referred to as the “Agreement for Water Exchange Operations of Lake Tahoe and Prosser Creek Reservoir,” this agreement was finalized in June 1959 and designated certain waters in Prosser Reservoir in the Truckee River Basin as “Tahoe Exchange Water.” By this agreement, when waters were to be released from Lake Tahoe for a minimum instream flow (50 cfs winter; 70 cfs summer) and when such releases from Lake Tahoe were not necessary for Floriston Rates due to normal flows elsewhere in the river, then an equal amount of water (exchange water) could be stored in Prosser Reservoir and used for releases at other times. Also see Truckee River Agreement [Nevada and California]. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) [Lake Tahoe – California and Nevada] — A bi-state regulatory agency created in July 1968 as part of a provisional California–Nevada Interstate Compact developed by the joint California–Nevada Interstate Compact Commission which was formed in 1995. The TRPA was the first bi-state regional environmental planning agency in the United States. The TRPA was intended to oversee land-use planning and environmental issues within the Lake Tahoe Basin and is dedicated to preserving the beauty of the region. Today, the TRPA leads the cooperative effort within the basin to preserve, restore, and enhance the unique natural and human environment of the region and is a leading partner in a comprehensive program which monitors water quality, air quality, and other threshold standard indicators. -

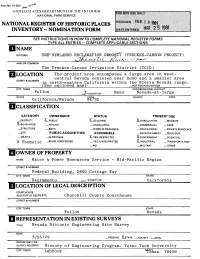

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 ^e>J-, AO-"1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS THE^-NEWLANDS RECLAMATION Pft9«JE T (TRUCKEE-CARSON PROJECT) AND/OR COMMON The Truckee-Carson Irrigation District (TCID) LOCATION The project area encompases a large area in west- central Nevada centered near Reno and a smaller area STREET & NUMBER in north-eastern California within the Sierra Nevada range (See enclosed map) NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Fallen X VICINITY OF Reno Nevada-at-large STATE COUNTY CODE California/Nevada CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X-PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED X.AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC X Thematic —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED XJNDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Water & Power Resources Service - Mid-Pacific Region STREET & NUMBER Federal Building, 2800 Cottage Way CITY, TOWN STATE Sacramento VICINITY OF California LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Churchill County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Nevada REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Nevada Historic Engineering Site Survey DATE 3725779 FEDERAL X.STATE COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS History of Engineering Program. Texas Tech University CITY, TOWN Lubbock 79409 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_QRIGINALSITE .XGOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE____ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The theme of this nomination is Conservation. -

Truckee River Appendix Cover

Final Environmental Impact Statement/Environmental Impact Report Truckee River Operating Agreement Cultural Resources Appendix January 2008 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Fish and Wildlife Service Bureau of Indian Affairs State of California Department of Water Resources Final Environmental Impact Statement/Environmental Impact Report Truckee River Operating Agreement Cultural Resources Appendix January 2008 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Fish and Wildlife Service Bureau of Indian Affairs State of California Department of Water Resources Cultural Resources Appendix Table of Contents Page CULTURAL RESOURCES APPENDIX .................................................................... 1 I. Section 1: Overview........................................................................................ 2 A. Study Area...............................................................................................................2 B. Prehistoric Settlement ..............................................................................................2 1. Pre-Archaic Period..........................................................................................2 2. Archaic Period................................................................................................2 3. Early Archaic Period.......................................................................................2 4. Middle Archaic Period....................................................................................3 -

River and Reservoir Operations Model, Truckee River Basin, California and Nevada, 1998

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey River and Reservoir Operations Model, Truckee River Basin, California and Nevada, 1998 Water-Resources Investigations Report 01-4017 Prepared in cooperation with the TRUCKEE–CARSON PROGRAM RIVER AND OPERATIONS MODEL, TRUCKEE RIVER BASIN, CALIFORNIA AND NEVADA, 1998 River and Reservoir Operations Model, Truckee River Basin, California and Nevada, 1998 By Steven N. Berris, Glen W. Hess, and Larry R. Bohman U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 01-4017 Prepared in cooperation with the TRUCKEE–CARSON PROGRAM Carson City, Nevada 2001 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government For additional information contact: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey 333 West Nye Lane, Room 203 Carson City, NV 89706–0866 email: [email protected] http://nevada.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract.................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Purpose and Scope ....................................................................................................................................................