Nowhere to Run: Big Game Wildlife in a Warming World 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wildlife Management in the National Parks

wildlife management IN THE NATIONAL PARKS wildlife management IN IHE NATIONAL PARKS 1969 REPRINT FROM ADMINISTRATIVE POLICIES FOR NATURAL AREAS OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR • NATIONAL PARK SERVICE For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT IN THE NATIONAL PARKS ADVISORY BOARD ON WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT, APPOINTED BY SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR UDALL A. S. Leopold (Chairman), S. A. Cain, C. M. Cottam, I. N. Gabrielson, T. L. Kimball March 4, 1963 Historical In the Congressional Act of 1916 which created the National Park Service, preservation of native animal' life was clearly specified as one of the pur poses of the parks. A frequently quoted passage of the Act states "... which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoy ment of future generations." In implementing this Act, the newly formed Park Service developed a philosophy of wildlife protection, which in that era was indeed the most obvious and immediate need in wildlife conservation. Thus the parks were established as refuges, the animal populations were protected from wildfire. For a time predators were controlled to protect the "good" ani mals from the "bad" ones, but this endeavor mercifully ceased in the 1930's. On the whole, there was little major change in the Park Service practice of wildlife management during the first 40 years of its existence. -

Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist

STATE OF NEVADA Steve Sisolak, Governor DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Tony Wasley, Director GAME DIVISION Brian F. Wakeling, Chief Mike Cox, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goat Staff Specialist Pat Jackson, Predator Management Staff Specialist Cody McKee, Elk Staff Biologist Cody Schroeder, Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist Western Region Southern Region Eastern Region Regional Supervisors Mike Scott Steve Kimble Tom Donham Big Game Biologists Chris Hampson Joe Bennett Travis Allen Carl Lackey Pat Cummings Clint Garrett Kyle Neill Cooper Munson Sarah Hale Ed Partee Kari Huebner Jason Salisbury Matt Jeffress Kody Menghini Tyler Nall Scott Roberts This publication will be made available in an alternative format upon request. Nevada Department of Wildlife receives funding through the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration. Federal Laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex, or disability. If you believe you’ve been discriminated against in any NDOW program, activity, or facility, please write to the following: Diversity Program Manager or Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Nevada Department of Wildlife 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Mailstop: 7072-43 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Suite 120 Arlington, VA 22203 Reno, Nevada 8911-2237 Individuals with hearing impairments may contact the Department via telecommunications device at our Headquarters at 775-688-1500 via a text telephone (TTY) telecommunications device by first calling the State of Nevada Relay Operator at 1-800-326-6868. NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE 2018-2019 BIG GAME STATUS This program is supported by Federal financial assistance titled “Statewide Game Management” submitted to the U.S. -

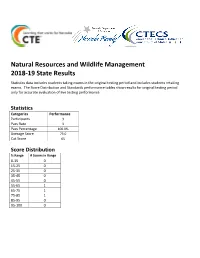

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management Statistics

Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 2018-19 State Results Statistics data includes students taking exams in the original testing period and includes students retaking exams. The Score Distribution and Standards performance tables show results for original testing period only for accurate evaluation of live testing performance. Statistics Categories Performance Participants 3 Pass Rate 3 Pass Percentage 100.0% Average Score 73.0 Cut Score 65 Score Distribution % Range # Scores in Range 0-15 0 15-25 0 25-35 0 35-45 0 45-55 0 55-65 1 65-75 1 75-85 1 85-95 0 95-100 0 Natural Resources and Wildlife Management 1) CONTENT STANDARD 1.0: EXPLORE NATURAL RESOURCE SCIENCE AND MANAGEMENT 75.93% 1) Performance Standard 1.1 : Investigate the Relationship Between Natural Resources and Society, Including Conflict Management 72.22% 1) 1.1.1 Define natural resource management 77.78% 3) 1.1.3 Describe human dependency and demands on natural resources 88.89% 4) 1.1.4 Explain natural resource conservation 66.67% 5) 1.1.5 Investigate the effects of multiple uses of natural resources (e.g., recreation, mining, agriculture, forestry, public lands grazing, etc.) 66.67% 6) 1.1.6 Analyze societal issues related to natural resource management 50% 2) Performance Standard 1.2 : Explain Interrelationships Between Natural Resources and Humans in Managing Natural Environments 86.67% 1) 1.2.1 Explain the effects and/or trade-off of population growth, greater energy consumption, and increased technology and development on natural resources and the environment 83.33% -

Antelope, Deer, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goats: a Guide to the Carpals

J. Ethnobiol. 10(2):169-181 Winter 1990 ANTELOPE, DEER, BIGHORN SHEEP AND MOUNTAIN GOATS: A GUIDE TO THE CARPALS PAMELA J. FORD Mount San Antonio College 1100 North Grand Avenue Walnut, CA 91739 ABSTRACT.-Remains of antelope, deer, mountain goat, and bighorn sheep appear in archaeological sites in the North American west. Carpal bones of these animals are generally recovered in excellent condition but are rarely identified beyond the classification 1/small-sized artiodactyl." This guide, based on the analysis of over thirty modem specimens, is intended as an aid in the identifi cation of these remains for archaeological and biogeographical studies. RESUMEN.-Se han encontrado restos de antilopes, ciervos, cabras de las montanas rocosas, y de carneros cimarrones en sitios arqueol6gicos del oeste de Norte America. Huesos carpianos de estos animales se recuperan, por 10 general, en excelentes condiciones pero raramente son identificados mas alIa de la clasifi cacion "artiodactilos pequeno." Esta glia, basada en un anaIisis de mas de treinta especlmenes modemos, tiene el proposito de servir como ayuda en la identifica cion de estos restos para estudios arqueologicos y biogeogrMicos. RESUME.-On peut trouver des ossements d'antilopes, de cerfs, de chevres de montagne et de mouflons des Rocheuses, dans des sites archeologiques de la . region ouest de I'Amerique du Nord. Les os carpeins de ces animaux, generale ment en excellente condition, sont rarement identifies au dela du classement d' ,I artiodactyles de petite taille." Le but de ce guide base sur 30 specimens recents est d'aider aidentifier ces ossements pour des etudes archeologiques et biogeo graphiques. -

Serologic Surveys for Natural Foci of Contagious Ecthyma Infection

FI.NAL REP.ORT (R.ESEARCH) State: Alaska Cooperators: Randall L. Zarnke and Kenneth A. Neiland Project No.: W-21-1 Project Title: Big Game Investigations Job No.: l8.1R Job Title: Serologic Surveys for Natural Foci of contag1ous Ecthyma Infection Period Covered: July 1, 1979 to J~~? ~0, 1~80 SUMMARY Contagious ecthyma (C. E. ) antibody prevalence in domestic sheep and goats in Interior Alaska du~ing 1978 was quite low (7-10%). This suggested a low level of transmission of the virus among these species during this time period. C. E. antibody prevalence in Dall sheep increased .from 30 percent in 1971 to 100 percent in 1978. This suggested an increased level of transmission to, and/or among, these animals during this period. Following a C.E. epizootic in a band of captive Dall sheep in 1977, antibody prevalence was 80 percent in this group of sheep. Less than l year later, prevalence had dropped to 10 percent in the ·same band. Thus it appeared that antibody produced in response to this . strain of C.E. is short-lived. Antibody was also detected in 10 of 22 free ranging muskoxen taken by sport hunters on Nunivak Island in 1978. Detectable antibody levels were not found in any of 19 muskoxen captured on the island in 1979. No antibody was found in a small number of captive muskoxen from Unalakleet. Several of the captive muskoxen were ·known to have been infected with C.E. within 1 to 2 years prior to the time of sampling. This further substantiates the belief that anti body produced in response to infection by the Alaskan strain of C.E. -

Thresholds and Drivers of Coral Calcification Responses to Climate Change

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Thresholds and drivers of coral calcification responses to climate change Kornder, N.A.; Riegl, B.M.; Figueiredo, J. DOI 10.1111/gcb.14431 Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in Global Change Biology License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kornder, N. A., Riegl, B. M., & Figueiredo, J. (2018). Thresholds and drivers of coral calcification responses to climate change. Global Change Biology, 24(11), 5084-5095. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14431 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 Received: 7 February 2018 | Revised: 15 June 2018 | Accepted: 6 August 2018 DOI: 10.1111/gcb.14431 PRIMARY RESEARCH ARTICLE Thresholds and drivers of coral calcification responses to climate change Niklas A. -

Bighorn Sheep, Moose, and Mountain Goats

Bighorn Sheep, Moose, and Mountain Goats Brock Hoenes Ungulate Section Manager, Wildlife Program WACs: 220-412-070 Big game and wild turkey auction, raffle, and special incentive permits. 220-412-080 Special hunting season permits. 220-415-070 Moose seasons, permit quotas, and areas. 220-415-120 2021 Bighorn sheep seasons and permit quotas. 220-415-130 2021 Mountain goat seasons and permit quotas. 1. Special Hunting Season Permits 2. Moose – Status, recommendations, public comment 3. Mountain Goat – Status, recommendations, public comment 4. Bighorn Sheep – Status, recommendations, public comment 5. Questions Content Department of Fish and Wildlife SPECIAL HUNTING SEASON PERMITS White‐Tailed DeerWAC 220-412-080 • Allow successful applicants for all big game special permits to return their permit to the Department for any Agree 77% reason two weeks prior to the Neutral 9% opening day of the season and to have their points restored Disagree 14% 1,553 Respondents • Remove the “once‐in‐a‐lifetime” Public Comment restriction for Mountain Goat Conflict • 223 comments, 1 email/letter Reduction special permit category • General (90 agree, 26 disagree) • Reissue permit (67) • >2 weeks (21) • No change (12) Department of Fish and Wildlife MOOSE • Primarily occur in White‐Tailed DeerNE and north-central Washington • Most recent estimate in 2016 indicated ~5,000 moose in NE • Annual surveys to estimate age and sex ratios (snow dependent) • Recent studies (2014-2018) in GMUs 117 and 124 indicated populations were declining • Poor body condition (adult female) • Poor calf survival • Wolf predation • Tick infestations • Substantial reduction in antlerless permits in 2018 Department of Fish and Wildlife MOOSE RECOMMENDATIONS 1. -

Global Change Biology, BIOL 26

Global Change Biology, BIOL 26 Professor: Caitlin Hicks Pries (LSC 349), Office hours Wed 2-3:30 pm & by appt. Class: Spring 2019, MWF 12:50-1:55, LSC 205 X-hours (Tuesdays 1:20-2:10, will be used occasionally to learn data analysis skills and as a time for group work). Learning objectives Mission Statement: Understand how humans are reshaping the processes of nature in the Anthropocene, articulate the repercussions of those changes for ecology and evolution, use global change datasets to answer biological questions, and be able to evaluate solutions that might mitigate the consequences. By the end of this course, you will be able to: • Describe the myriad of ways humans are altering earth’s atmosphere, land, and water. • Understand how global change is fundamentally altering the way species interact with their environments. • Apply concepts and theory of ecology and evolution to case studies detailing the effects of global change on species, species interactions, and carbon and nutrient cycling. • Understand, summarize, and critically evaluate primary scientific literature on global change biology including how scientists use gradients, experiments, and models to investigate global change. • Develop and answer scientific questions by using R to access, organize, and graph actual data sets. • Articulate the pros and cons of potential solutions to global change issues and to be able to defend your position on potential solutions. Course description We are currently living in the Anthropocene era where humans are having an outsize effect on the Earth’s environment through the burning of fossil fuels, the large-scale conversion of land for agriculture, the modification of water courses for flood control and energy, and the use of fertilizers, to name a few. -

For-74: a Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning

FOR-74 A Guide to Urban Habitat Conservation Planning Thomas G. Barnes, Extension Wildlife Specialist Lowell Adams, National Institute for Urban Wildlife entuckians value their forests and Kother natural resources for aes- Guidelines for Considering Wildlife in the Urban Development thetic, recreational, and economic Process significance, so over the past several Promote habitats that will have the food, cover, water, and living space that decades they have become increasingly all wildlife require by following these guidelines: concerned about the loss of wildlife • Before development, maximize open space and make an effort to protect the habitat and greenspace. Urban and most valuable wildlife habitat by placing buildings on less important portions suburban development is one of the of the site. Choosing cluster development, which is flexible, can help. leading causes of this loss: A recent • Provide water, and design stormwater control impoundments to benefit wildlife. study indicated that every day in • Use native plants that have value for wildlife as well as aesthetic appeal. Kentucky more than 100 acres of rural • Provide bird-feeding stations and nest boxes for cavity-nesting birds like land is being converted to urban house wrens and wood ducks. development. • Educate residents about wildlife conservation, using, for example, informa- Because concern for loss of tion packets or a nature trail through open space. greenspace is not new, we have for • Ensure a commitment to managing urban wildlife habitats. some time created attractive urban greenspace environments with our parks and backyards. These The publication can also be useful to A landscape is a large area com- greenspaces have been created not so the average homeowner in understand- posed of ecosystems (the plants, much for wildlife habitats as for people ing the complex issues involved in animals, other living organisms, and to enjoy, but the potential for wildlife landscape planning and wildlife their physical surroundings). -

Bighorn Sheep Statewide Management Plan

UTAH BIGHORN SHEEP STATEWIDE MANAGEMENT PLAN UTAH DIVISION OF WILDLIFE RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES UTAH DIVISION OF WILDLIFE RESOURCES STATEWIDE MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR BIGHORN SHEEP I. PURPOSE OF THE PLAN A. General This document is the Statewide Management Plan for bighorn sheep in Utah (hereafter referred to as the “Plan”). This Plan provides overall guidance and direction to Utah’s bighorn sheep management program. This Plan assesses current information on bighorn sheep, identifies issues and concerns relating to bighorn sheep management in Utah, and establishes goals and objectives for future bighorn management programs. Strategies are also outlined to achieve goals and objectives. This Plan helps determine priorities for bighorn management and provide the overall direction for management plans on individual bighorn units throughout the state. Unit management plans will be presented to the Utah Wildlife Board when one of the following criteria are met: 1) a new bighorn sheep unit is being proposed, 2) the current unit requires a significant boundary change, 3) a change to the unit population objective is being proposed, or 4) the unit has not yet had a management plan approved by the Utah Wildlife Board. All other changes to unit management plans will be approved by the Division Director. This Plan, among other things, outlines a variety of measures designed to abate or mitigate the risk of comingling and pathogen transmission between domestic and wild bighorn sheep. This Plan is not intended to be utilized to involuntarily alter domestic sheep grazing operations in Utah. The only mechanism acceptable to the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (UDWR) for altering domestic sheep grazing practices to avoid risk of comingling is through voluntary actions undertaken by the individual grazers. -

Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management

CONTENTS BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management - Volume 1 No. of Pages: 458 ISBN: 978-1-905839-20-9 (eBook) ISBN: 978-1-84826-920-0 (Print Volume) Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management - Volume 2 No. of Pages: 428 ISBN: 978-1-905839-21-6 (eBook) ISBN: 978-1-84826-921-7 (Print Volume) For more information of e-book and Print Volume(s) order, please click here Or contact : [email protected] ©Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND HABITAT MANAGEMENT CONTENTS Preface xv VOLUME I Biodiversity Conservation and Habitat Management : An Overview 1 Francesca Gherardi, Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e Genetica, Università di Firenze, Italy Claudia Corti, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco CA, U.S.A. Manuela Gualtieri, Dipartimento di Scienze Zootecniche, Università di Firenze, Italy 1. Introduction: the amount of biological diversity 2. Diversity in ecosystems 2.1. African wildlife systems 2.2. Australian arid grazing systems 3. Measures of biodiversity 3.1. Species richness 3.2. Shortcuts to monitoring biodiversity: indicators, umbrellas, flagships, keystones, and functional groups 4. Biodiversity loss: the great extinction spasm 5. Causes of biodiversity loss: the “evil quartet” 5.1. Over-harvesting by humans 5.2. Habitat destruction and fragmentation 5.3. Impacts of introduced species 5.4. Chains of extinction 6. Why conserve biodiversity? 7. Conservation biology: the science of scarcity 8. Evaluating the status of a species: extinct until proven extant 9. What is to be done? Conservation options 9.1. Increasing our knowledge 9.2. Restore habitats and manage them 9.3. -

Wildlife Management Activities and Practices

WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES AND PRACTICES COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT PLANNING GUIDELINES for the Edwards Plateau and Cross Timbers & Prairies Ecological Regions Revised April 2010 The following Texas Parks & Wildlife Department staff have contributed to this document: Mike Krueger, Technical Guidance Biologist – Lampasas Mike Reagan, Technical Guidance Biologist -- Wimberley Jim Dillard, Technical Guidance Biologist -- Mineral Wells (Retired) Kirby Brown, Private Lands and Habitat Program Director (Retired) Linda Campbell, Program Director, Private Lands & Public Hunting Program--Austin Linda McMurry, Private Lands and Public Hunting Program Assistant -- Austin With Additional Contributions From: Kevin Schwausch, Private Lands Biologist -- Burnet Terry Turney, Rare Species Biologist--San Marcos Trey Carpenter, Manager, Granger Wildlife Management Area Dale Prochaska, Private Lands Biologist – Kerr Wildlife Management Area Nathan Rains, Private Lands Biologist – Cleburne TABLE OF CONTENTS Comprehensive Wildlife Management Planning Guidelines Edwards Plateau and Cross Timbers & Prairies Ecological Regions Introduction Specific Habitat Management Practices HABITAT CONTROL EROSION CONTROL PREDATOR CONTROL PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL WATER PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL FOOD PROVIDING SUPPLEMENTAL SHELTER CENSUS APPENDICES APPENDIX A: General Habitat Management Considerations, Recommendations, and Intensity Levels APPENDIX B: Determining Qualification for Wildlife Management Use APPENDIX C: Wildlife Management Plan Overview APPENDIX D: Livestock