Thoracentesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coding Billing

CodingCoding&Billing FEBRUARY 2020 Quarterly Editor’s Letter Welcome to the February issue of the ATS Coding and Billing Quarterly. There are several important updates about the final Medicare rules for 2020 that will be important for pulmonary, critical care and sleep providers. Additionally, there is discussion of E/M documentation rules that will be coming in 2021 that practices might need some time to prepare for, and as always, we will answer coding, billing and regulatory compliance questions submitted from ATS members. If you are looking for a more interactive way to learn about the 2020 Medicare final rules, there is a webinar on the ATS website that covers key parts of the Medicare final rules. But before we get to all this important information, I have a request for your help. EDITOR ATS Needs Your Help – Recent Invoices for Bronchoscopes and PFT Lab ALAN L. PLUMMER, MD Spirometers ATS RUC Advisor TheA TS is looking for invoices for recently purchased bronchoscopes and ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS: PFT lab spirometer. These invoices will be used by theA TS to present practice KEVIN KOVITZ, MD expense cost equipment to CMS to help establish appropriate reimbursement Chair, ATS Clinical Practice Committee rates for physician services using this equipment. KATINA NICOLACAKIS, MD Member, ATS Clinical Practice Committee • Invoices should not include education or service contract as those ATS Alternate RUC Advisorr are overhead and cannot be considered by CMS for this portion of the STEPHEN P. HOFFMANN, MD Member, ATS Clinical Practice Committee formula and payment rates. ATS CPT Advisor • Invoices can be up to five years old. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Annex 2. List of Procedure Case Rates (Revision 2.0)

ANNEX 2. LIST OF PROCEDURE CASE RATES (REVISION 2.0) FIRST CASE RATE RVS CODE DESCRIPTION Health Care Case Rate Professional Fee Institution Fee Integumentary System Skin, Subcutaneous and Accessory Structures Incision and Drainage Incision and drainage of abscess (e.g., carbuncle, suppurative hidradenitis, 10060 3,640 840 2,800 cutaneous or subcutaneous abscess, cyst, furuncle, or paronychia) 10080 Incision and drainage of pilonidal cyst 3,640 840 2,800 10120 Incision and removal of foreign body, subcutaneous tissues 3,640 840 2,800 10140 Incision and drainage of hematoma, seroma, or fluid collection 3,640 840 2,800 10160 Puncture aspiration of abscess, hematoma, bulla, or cyst 3,640 840 2,800 10180 Incision and drainage, complex, postoperative wound infection 5,560 1,260 4,300 Excision - Debridement 11000 Debridement of extensive eczematous or infected skin 10,540 5,040 5,500 Debridement including removal of foreign material associated w/ open 11010 10,540 5,040 5,500 fracture(s) and/or dislocation(s); skin and subcutaneous tissues Debridement including removal of foreign material associated w/ open 11011 fracture(s) and/or dislocation(s); skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle fascia, 11,980 5,880 6,100 and muscle Debridement including removal of foreign material associated w/ open 11012 fracture(s) and/or dislocation(s); skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle fascia, 12,120 6,720 5,400 muscle, and bone 11040 Debridement; skin, partial thickness 3,640 840 2,800 11041 Debridement; skin, full thickness 3,640 840 2,800 11042 Debridement; skin, and -

ANMC Specialty Clinic Services

Cardiology Dermatology Diabetes Endocrinology Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) Gastroenterology General Medicine General Surgery HIV/Early Intervention Services Infectious Disease Liver Clinic Neurology Neurosurgery/Comprehensive Pain Management Oncology Ophthalmology Orthopedics Orthopedics – Back and Spine Podiatry Pulmonology Rheumatology Urology Cardiology • Cardiology • Adult transthoracic echocardiography • Ambulatory electrocardiology monitor interpretation • Cardioversion, electrical, elective • Central line placement and venous angiography • ECG interpretation, including signal average ECG • Infusion and management of Gp IIb/IIIa agents and thrombolytic agents and antithrombotic agents • Insertion and management of central venous catheters, pulmonary artery catheters, and arterial lines • Insertion and management of automatic implantable cardiac defibrillators • Insertion of permanent pacemaker, including single/dual chamber and biventricular • Interpretation of results of noninvasive testing relevant to arrhythmia diagnoses and treatment • Hemodynamic monitoring with balloon flotation devices • Non-invasive hemodynamic monitoring • Perform history and physical exam • Pericardiocentesis • Placement of temporary transvenous pacemaker • Pacemaker programming/reprogramming and interrogation • Stress echocardiography (exercise and pharmacologic stress) • Tilt table testing • Transcutaneous external pacemaker placement • Transthoracic 2D echocardiography, Doppler, and color flow Dermatology • Chemical face peels • Cryosurgery • Diagnosis -

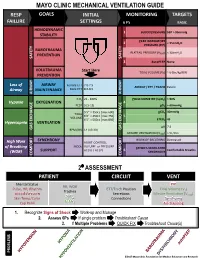

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Pneumothorax Following Thoracentesis a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

REVIEW ARTICLE Pneumothorax Following Thoracentesis A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Craig E. Gordon, MD, MS; David Feller-Kopman, MD; Ethan M. Balk, MD, MPH; Gerald W. Smetana, MD Background: Little is known about the factors related to but this was nonsignificant within studies directly com- the development of pneumothorax following thoracente- paring this factor (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.2-2.3). Pneumotho- sis. We aimed to determine the mean pneumothorax rate rax was more likely following therapeutic thoracentesis (OR, following thoracentesis and to identify risk factors for pneu- 2.6; 95% CI, 1.8-3.8), in conjunction with periprocedural mothorax through a systematic review and meta-analysis. symptoms (OR, 26.6; 95% CI, 2.7-262.5), and in associa- tion with, although nonsignificantly, mechanical ventila- Methods: We reviewed MEDLINE-indexed studies from tion (OR, 4.0; 95% CI, 0.95-16.8). Two or more needle January 1, 1966, through April 1, 2009, and included stud- passes conferred a nonsignificant increased risk of pneu- ies of any design with at least 10 patients that reported mothorax (OR, 2.5; 95% CI, 0.3-20.1). the pneumothorax rate following thoracentesis. Two in- vestigators independently extracted data on the pneu- Conclusions: Iatrogenic pneumothorax is a common mothorax rate, risk factors for pneumothorax, and study complication of thoracentesis and frequently requires methodological quality. chest tube insertion. Real-time ultrasonography use is a modifiable factor that reduces the pneumothorax rate. Results: Twenty-four studies reported pneumothorax rates Performance of thoracentesis for therapeutic purposes and following 6605 thoracenteses. The overall pneumothorax in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation confers a rate was 6.0% (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.6%-7.8%), higher likelihood of pneumothorax. -

28 Thoracentesis (Assist) 223

PROCEDURE Thoracentesis (Assist) 28 Susan Yeager PURPOSE: Thoracentesis is performed to assist in the diagnosis and therapeutic management of patients with pleural effusions. PREREQUISITE NURSING hypotension, cough, pain, visceral injury, and reexpansion 4–6 KNOWLEDGE pulmonary edema. • The most common complications from pleural aspiration • Thoracentesis is performed with insertion of a needle or are pneumothorax, pain, hemorrhage, and procedure a catheter into the pleural space, which allows for removal failure. The most serious complication is visceral injury. 5 of pleural fl uid. • Hypotension can occur as part of the vasovagal reaction, • Pleural effusions are defi ned as the accumulation of fl uid causing bradycardia, during or hours after the procedure. in the pleural space that exceeds 10 mL and results from If it occurs during the procedure, cessation of the proce- the overproduction of fl uid or disruption in fl uid dure and intravenous (IV) atropine may be necessary. If reabsorption. 1 hypotension occurs after the procedure, it is likely the • Diagnostic thoracentesis is indicated for differential diag- result of fl uid shifting from pleural effusion reaccumula- nosis for patients with pleural effusion of unknown etiol- tion. In this situation, the patient is likely to respond to ogy. A diagnostic thoracentesis may be repeated if initial fl uid resuscitation. 7 results fail to yield a diagnosis. • Development of cough generally initiates toward the • Therapeutic thoracentesis is indicated to relieve the symp- end of the procedure and should result in procedure toms (e.g., dyspnea, cough, hypoxemia, or chest pain) cessation. caused by a pleural effusion. • Reexpansion pulmonary edema is thought to occur from • Samples of pleural fl uid are analyzed and assist in distin- overdraining of fl uid too quickly. -

Physicians As Assistants at Surgery: 2016 Update

Physicians as Assistants at Surgery: 2016 Update Participating Organizations: American College of Surgeons American Academy of Ophthalmology American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery American Association of Neurological Surgeons American Pediatric Surgical Association American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons American Society of Plastic Surgeons American Society of Transplant Surgeons American Urological Association Congress of Neurological Surgeons Society for Surgical Oncology Society for Vascular Surgery Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Physicians as Assistants at Surgery: 2016 Update INTRODUCTION This is the seventh edition of Physicians as Assistants at Surgery, a study first undertaken in 1994 by the American College of Surgeons and other surgical specialty organizations. The study reviews all procedures listed in the “Surgery” section of the 2016 American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology (CPT TM). Each organization was asked to review new codes since 2013 that are applicable to their specialty and determine whether the operation requires the use of a physician as an assistant at surgery: (1) almost always; (2) almost never; or (3) some of the time. The results of this study are presented in the accompanying report, which is in a table format. This table presents information about the need for a physician as an assistant at surgery. Also, please note that an indication that a physician would “almost never” be needed to assist at surgery for some procedures does NOT imply that a physician is never needed. The decision to request that a physician assist at surgery remains the responsibility of the primary surgeon and, when necessary, should be a payable service. -

Icd-9-Cm (2010)

ICD-9-CM (2010) PROCEDURE CODE LONG DESCRIPTION SHORT DESCRIPTION 0001 Therapeutic ultrasound of vessels of head and neck Ther ult head & neck ves 0002 Therapeutic ultrasound of heart Ther ultrasound of heart 0003 Therapeutic ultrasound of peripheral vascular vessels Ther ult peripheral ves 0009 Other therapeutic ultrasound Other therapeutic ultsnd 0010 Implantation of chemotherapeutic agent Implant chemothera agent 0011 Infusion of drotrecogin alfa (activated) Infus drotrecogin alfa 0012 Administration of inhaled nitric oxide Adm inhal nitric oxide 0013 Injection or infusion of nesiritide Inject/infus nesiritide 0014 Injection or infusion of oxazolidinone class of antibiotics Injection oxazolidinone 0015 High-dose infusion interleukin-2 [IL-2] High-dose infusion IL-2 0016 Pressurized treatment of venous bypass graft [conduit] with pharmaceutical substance Pressurized treat graft 0017 Infusion of vasopressor agent Infusion of vasopressor 0018 Infusion of immunosuppressive antibody therapy Infus immunosup antibody 0019 Disruption of blood brain barrier via infusion [BBBD] BBBD via infusion 0021 Intravascular imaging of extracranial cerebral vessels IVUS extracran cereb ves 0022 Intravascular imaging of intrathoracic vessels IVUS intrathoracic ves 0023 Intravascular imaging of peripheral vessels IVUS peripheral vessels 0024 Intravascular imaging of coronary vessels IVUS coronary vessels 0025 Intravascular imaging of renal vessels IVUS renal vessels 0028 Intravascular imaging, other specified vessel(s) Intravascul imaging NEC 0029 Intravascular -

Intensive Care Unit Patients

Revised 2020 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Intensive Care Unit Patients Variant 1: Admission or transfer to intensive care unit. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography chest portable Usually Appropriate ☢ US chest May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) O Variant 2: Stable intensive care unit patient. No change in clinical status. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography chest portable May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) ☢ US chest Usually Not Appropriate O Variant 3: Intensive care unit patient with clinically worsening condition. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography chest portable Usually Appropriate ☢ US chest May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) O Variant 4: Intensive care unit patient following support device placement. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography chest portable Usually Appropriate ☢ US chest May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) O Variant 5: Intensive care unit patient. Post chest tube or mediastinal tube removal. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level Radiography chest portable May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) ☢ US chest Usually Not Appropriate O ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Intensive Care Unit Patients INTENSIVE CARE UNIT PATIENTS Expert Panel on Thoracic Imaging: Archana T. Laroia, MDa; Edwin F. Donnelly, MD, PhDb; Travis S. Henry, MDc; Mark F. Berry, MDd; Phillip M. Boiselle, MDe; Patrick M. Colletti, MDf; Christopher T. Kuzniewski, MDg; Fabien Maldonado, MDh; Kathryn M. Olsen, MDi; Constantine A. Raptis, MDj; Kyungran Shim, MDk; Carol C. Wu, MDl; Jeffrey P. Kanne, MD.m Summary of Literature Review Introduction/Background This publication discusses the utility of chest radiographs and chest ultrasound (US) in the intensive care unit (ICU) setting. -

Development of the ICD-10 Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS)

Development of the ICD-10 Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) Richard F. Averill, M.S., Robert L. Mullin, M.D., Barbara A. Steinbeck, RHIT, Norbert I. Goldfield, M.D, Thelma M. Grant, RHIA, Rhonda R. Butler, CCS, CCS-P The International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) has been developed as a replacement for Volume 3 of the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision (ICD-9-CM). The development of ICD-10-PCS was funded by the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).1 ICD-10- PCS has a multiaxial seven character alphanumeric code structure that provides a unique code for all substantially different procedures, and allows new procedures to be easily incorporated as new codes. ICD10-PCS was under development for over five years. The initial draft was formally tested and evaluated by an independent contractor; the final version was released in the Spring of 1998, with annual updates since the final release. The design, development and testing of ICD-10-PCS are discussed. Introduction Volume 3 of the International Classification of Diseases 9th Revision Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) has been used in the U.S. for the reporting of inpatient pro- cedures since 1979. The structure of Volume 3 of ICD-9-CM has not allowed new procedures associated with rapidly changing technology to be effectively incorporated as new codes. As a result, in 1992 the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) funded a project to design a replacement for Volume 3 of ICD-9-CM. -

Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS)

AY 130108 Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery Jay B. Brodskya and Edmond Cohenb Video-assisted thoracic surgery is finding an ever-increasing Introduction role in the diagnosis and treatment of a wide range of thoracic Thoracoscopy involves intentionally creating a pneu- disorders that previously required sternotomy or open mothorax and then introducing an instrument through thoracotomy. The potential advantages of video-assisted the chest wall to visualize the intrathoracic structures. thoracic surgery include less postoperative pain, fewer Direct visual inspection of the pleural cavity has been operative complications, shortened hospital stay and reduced performed since 1910, when Jacobeaus ®rst used a costs. The following review examines the surgical and thoracoscope to diagnose and treat effusions secondary anesthetic considerations of video-assisted thoracic surgery, to tuberculosis. The recent application of video cameras with an emphasis on recently published articles. Curr Opin to thoracoscopes for high-de®nition magni®ed viewing, Anaesthesiol 13:000±000. # 2000 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. coupled with the development of sophisticated surgical instruments and stapling devices, has greatly expanded the ability of the endoscopist to do increasingly more complex procedures using thoracoscopy. aDepartment of Anesthesiology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA; and bDepartment of Anesthesiology, The Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, USA Compared with open thoracotomy, video-assisted thor- acoscopic surgery (VATS) is considered to be `minimally Correspondence to Jay B Brodsky at the Department of Anesthesiology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA Tel: +1 650 725 5869; invasive'. The patient population tends to be either very fax: +1 650 725 8544; email: [email protected] healthy individuals undergoing diagnostic procedures, or Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 2000, 13:000±000 high-risk patients undergoing VATS to avoid open thoracotomy.