Summative Evaluation of Dragon Tales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A-Z Series Recommendations by Level Summer Is the Perfect Time to Get Lost in a Book Series!

A-Z Series Recommendations by Level Summer is the perfect time to get lost in a book series! A, B, & C Berenstain Bears, Big Bear, Small Bear / Berenstain Biscuit (I Can Read! Level)/ Capucilli Brand New Readers / various authors Clarence the Dragon / Dufresne Dear Zoo and Friends / Campbell Huggles / Crowley I Like Me! / Carlson Oliver the Cat / Renton Tiny the Snow Dog / Meister Tug the Pup and Friends / Wood D Bob Books / Maslen Cat the Cat / Willems Clifford (Level 1) / Bridwell Dr. Seuss Bright and Early Books for Beginning Beginners / various authors I Can Read (My First Shared Reading) / various authors Mrs. Wishy Washy / Crowley Puppy Mudge / Rylant Sam / Lindgren E Little Critter (My First Shared Reading) / Mayer Mittens (My First Shared Reading) / Hartung Pete the Cat (My First I Can Read) / Dean Spot / Hill What People Do Best / Numeroff F Are You Ready to Play Outside? / Willems Biscuit (I Can Read editions) / Capucilli Can I Play Too? / Willems Digger the Dinosaur (My First Shared Reading) / Dolrlich Dumb Bunnies / Pilkey Everything Goes (My First Shared Reading) / Biggs JoJo (I Can Read editions) / O’Connor Mia (My First Shared Reading) / Farley Mr. Men and Little Miss (Reading Ladder) / Hargreaves G Berenstain Bears (Beginning Reading edition) / Berenstain Elephant and Piggie / Willems Eloise (Ready-to-Read) / McNamara Hi! Fly Guy / Arnold Nuts / Litwin Pigeon / Willems Pete the Cat (I Can Read) / Dean H Crabby / Fenske Elephant and Piggie Like Reading / assorted Frog and Friends / Bunting If You Give a … a … / Numeroff Katie Woo / Manushkin Little Critter / Mayer Martha Speaks (readers level 2) / Meddaugh Pictureback(R) / various authors Star Wars: The Clone Wars (DK Readers Pre-level 1) / Richards What is a … (animal) / Schaefer What … Can’t Do / Wood I A …'s Life (nature series) / Himmelman About .. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

AETN Resource Guide for Child Care Professionals

AAEETTNN RReessoouurrccee GGuuiiddee ffoorr CChhiilldd CCaarree PPrrooffeessssiioonnaallss Broadcast Schedule PARENTING COUNTS RESOURCES A.M. HELP PARENTS 6:00 Between the Lions The resource-rich PARENTING 6:30 Maya & Miguel COUNTS project provides caregivers 7:00 Arthur and parents a variety of multi-level 7:30 Martha Speaks resources. Professional development 8:00 Curious George workshops presented by AETN provide a hands-on 8:30 Sid the Science Kid opportunity to explore and use the videos, lesson plans, 9:00 Super WHY! episode content and parent workshop formats. Once child 9:30 Clifford the Big Red Dog care providers are trained using the materials, they are able to 10:00 Sesame Street conduct effective parent workshops and provide useful 11:00 Dragon Tales handouts to parents and other caregivers. 11:30 WordWorld P.M. PARENTS AND CAREGIVERS 12:00 Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood CAN ASK THE EXPERTS 12:30 Big Comfy Couch The PBS online Expert Q&A gives 1:00 Reading Rainbow parents and caregivers the opportunity to 1:30 Between the Lions ask an expert in the field of early childhood 2:00 Caillou development for advice. The service includes information 2:30 Curious George about the expert, provides related links and gives information 3:00 Martha Speaks about other experts. Recent subjects include preparing 3:30 Wordgirl children for school, Internet safety and links to appropriate 4:00 Fetch with Ruff Ruffman PBS parent guides. The format is easy and friendly. To ask 4:30 Cyberchase the experts, visit http://www.pbs.org/parents/issuesadvice. STAY CURRENT WITH THE FREE STATIONBREAK NEWS FOR EDUCATORS AETN StationBreak News for Educators provides a unique (and free) resource for parents, child care professionals and other educators. -

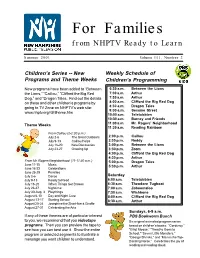

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn Summer 2001 Volume III, Number 2 Children’s Series -- New Weekly Schedule of Programs and Theme Weeks Children’s Programming New programs have been added to “Between 6:30 a.m. Between the Lions the Lions,” “Caillou,” “Clifford the Big Red 7:00 a.m. Arthur Dog,” and “Dragon Tales. Find out the details 7:30 a.m. Arthur on these and other children’s programs by 8:00 a.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog going to TV Zone on NHPTV’s web site: 8:30 a.m. Dragon Tales 9:00 a.m. Sesame Street www.nhptv.org/rtl/rtlhome.htm 10:00 a.m. Teletubbies 10:30 a.m. Barney and Friends Theme Weeks 11:00 a.m. Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood 11:30 a.m. Reading Rainbow From Caillou (2-2:30 p.m.) July 2-6 The Great Outdoors 2:00 p.m. Caillou July 9-13 Caillou Helps 2:30 p.m. Noddy July 16-20 New Discoveries 3:00 p.m. Between the Lions July 23-27 Growing Up 3:30 p.m. Zoom 4:00 p.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog 4:30 p.m. Arthur From Mr. Rogers Neighborhood (11-11:30 a.m.) 5:00 p.m. Dragon Tales June 11-15 Music 5:30 p.m. Arthur June 18-22 Celebrations June 25-29 Families July 2-6 Dance Saturday July 9-13 Ready to Read 6:00 a.m. Teletubbies July 16-20 When Things Get Broken 6:30 a.m. -

Shoreline Sonata: a Long Island Love Story

Vol. 15 No. 5 Cry for Help Personal stories June Guide provide new insights Online! on teen depression may FINAL PRINT and suicide Wednesday, May 6 in focus ISSUE at 10 p.m. Details on back page NATURE “Victoria Falls” Explore the largest waterfall on earth Wednesday, May 20 at 8 p.m. Credit: ©Charlie Hamilton James Frankie Manning: Still Swinging The NYC dance legend turns 95 Thursday, May 28 Shoreline Sonata: at 10:30 p.m. A Long Island Love Story WLIW21’s new production showcases dazzling views of Montauk and other summer destinations Thursday, May 21 at 8 p.m. Preview video at wliw.org Credit: Ralph Gabriner cover mayhighlights Shoreline Sonata: A Long Island Cry for Help Love Story On Wednesday, May 6 at 10 p.m., a new documentary addresses the Premiering Thursday, critical issues surrounding teen depression and suicide, exploring treatments, mental health testing and community healing programs story May 21 at 8 p.m., to give parents and educators a basis for recognizing WLIW21’s new the warning signs of teens in trouble. Profiles production celebrates include Clarkstown North High School in Rockland the natural beauty County, NY, where an online community lets teens and mystery anonymously air their problems and seek support surrounding the from their peers and professionals; and former places where land Rutgers University student Stacy Hollingsworth. and water meet on A straight-A student and gifted musician, Stacy Long Island. Scenic successfully hid her depression and suicidal thoughts until she made the difficult transition images from sunrise to college, where she ultimately founded to moonscape are Rutgers’ first on-campus chapter of accompanied by the National Alliance for the Mentally poetry inspired Ill. -

Olson Medical Clinic Services Que Locura Noticiero Univ

TVetc_35 9/2/09 1:46 PM Page 6 SATURDAY ** PRIME TIME ** SEPTEMBER 5 TUESDAY ** AFTERNOON ** SEPTEMBER 8 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> The Lawrence Welk Show ‘‘When Guy Lombardo As Time Goes Keeping Up May to Last of the The Red Green Soundstage ‘‘Billy Idol’’ Rocker Austin City Limits ‘‘Foo Fighters’’ Globe Trekker Classic furniture in KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Barney & Friends The Berenstain Between the Lions Wishbone ‘‘Mixed Dragon Tales (S) Arthur (S) (EI) WordGirl ‘‘Mr. Big; The Electric Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase Nightly Business KUSD d V the Carnival Comes’’; ‘‘Baby and His Royal By Appearances December Summer Wine Show ‘‘Comrade Billy Idol performs his hits to a Grammy Award-winning group Foo Hong Kong; tribal handicrafts of the Street (S) (EI) (N) (S) (EI) Bears (S) (S) (EI) Breeds’’ (S) (EI) Book Ends’’ (S) (EI) Company (S) (EI) Ruffman (S) (EI) ‘‘Codename: Icky’’ Report (N) (S) Elephant Walk’’; ‘‘Tiger Rag.’’ Canadians (S) Harold’’ (S) packed house. (S) Fighters perform. (S) Makonde tribes. (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The Faith Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The King Is Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show (Season News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News News (N) (S) The Insider (N) Law & Order: Criminal Intent A Law & Order A firefighter and his Law & Order: Special Victims News (N) (S) Saturday Night Live Anne Hathaway; the Killers. -

Menlo Park Juvi Dvds Check the Online Catalog for Availability

Menlo Park Juvi DVDs Check the online catalog for availability. List run 09/28/12. J DVD A.LI A. Lincoln and me J DVD ABE Abel's island J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Ociee Nash J DVD ADV The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin. J DVD ADV The adventures of Pinocchio J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE 2 Agent Cody Banks 2 J DVD AIR Air Bud J DVD AIR Air buddies J DVD ALA Aladdin J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALICE Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALL All dogs go to heaven J DVD ALL All about fall J DVD ALV Alvin and the chipmunks. -

CBC ENGLISH TELEVISION SCHEDULE 2000/2001 CCG Joint Sports Program Suppliers

CBC ENGLISH TELEVISION SCHEDULE 2000/2001 CCG Joint Sports Program Suppliers TIME SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 6:00 AM 6:30 CBC Morning 7:00 AM Arthur Magic School Bus 7:30 Rolie, Polie, Olie CBC4 Kids Horrible Histories 8:00:AM CBC4 Kids 8:30 9:00 AM Coronation Franklin Clifford: The Big Red Dog 9:30 Street Scoop & Doozer Get Set For Life CBC4 Kids 10:00 AM Little Bear 10:30 Mr. Dress-up Sesame Park 11:00 AM Riverdale Noddy Theodore Tugboat 11:30 12:00 PM Moving On This Hour Has 22 Minutes 12:30 Man Alive The Red Green Show 1:00 PM OTRA* 1:30 Country Canada North of 60 2:00 PM Sunday CBC 2:30 Encore Road to Avonlea Sports 3:00 PM Best of Canadian Gardener Saturday Current Affairs Coronation Street 3:30 Riverdale 4:00 PM The Nature CBC4 Kids 4:30 of Things 5:00 PM The Wonderful Pelswick The Simpsons 5:30 World of Disney Street Cents JonoVision Basic block program schedule *On the Road Again CBC ENGLISH TELEVISION SCHEDULE 2000/2001 CCG Joint Sports Program Suppliers TIME SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 6:00 PM The Saturday Wonderful News: 30 minutes local / 30 minutes national Report 6:30 World of Labatt Disney Saturday Night 7:00 PM Royal Canadian On The Road Again This Hour Has Wind at Air Farce Life & Times Pelswick 22 Minutes 7:30 My Back It's A Living Country Canada Our Hero Just For Laughs 8:00 PM This Hour Has Royal Canada: A 22 Minutes Marketplace Canadian People's the fifth estate CBC Thursday Air Farce Hockey Night 8:30 History Made in Canada Venture / Specials The Red In -

August 1-9, 2009

www.oeta.tv KETA-TV 13 Oklahoma City KOED-TV 11 Tulsa KOET-TV 3 Eufaula KWET-TV 12 Cheyenne August 2009 Volume 36 Number 2 A Publication of the Oklahoma Educational Television Authority Foundation, Inc. AUGUST 1-9, 2009 AUGUST At a Glance AUGUSTFEST LOCAL FOCUS HISTORY & CULTURE SCIENCE & NATURE Tony Bennett: An Oklahoma Horizon Time Team NOVAscienceNow American Classic Sundays at 3 p.m. America Special Tuesdays @ 8 p.m. August 2 at 7 p.m. August 19 at 7 p.m. page 2 9 10 11 2 TONY BENNETT AN AMERICAN CLASSIC f Sunday August 2 at 7 p.m. The ground-breaking television event features breath- taking stage productions that take the viewer on an emotional musical journey of this legendary entertain- f er’s life, re-creating the seminal venues of his career. Saturday August 1 at 7 p.m. Tony performs duets of his greatest hits with some of Hosted by Mary Lou today’s greatest artists – “The Best Is Yet to Come” Metzger, this all-new with Diana Krall, “Rags to Riches” with Elton John and special highlights “For Once in My Life” with Stevie Wonder, to name outstanding musical a few. Woven throughout the special are narratives production numbers by special guests such as Billy Crystal, John Travolta from the past ten and Robert De Niro. The special ends with Tony’s solo years. Members of the performance of his signature song “I Left My Heart in Welk Musical Fam- San Francisco.” ily are spotlighted in short biographies, illustrated by their own personal collection of photographs. -

Need to Know

may 2010 Need to Know Series Premiere Fri 7th, 8:30 p.m. thirteen.org/ needtoknow FEATURED THIS MONTH Need to Know thirteeN coNtiNues its tradition of providing groundbreaking news programming with Need to Know Fridays, 8:30 p.m. on PBS, a new weekly news & public affairs series beginning May 7th premiering this month online and on-air. Co-anchored and 24/7 at thirteen.org/ by acclaimed journalists Alison Stewart and Jon needtoknow Meacham, it features stories on the economy, the environment and energy, health, security, and culture. Stephen Segaller, VP of Content at WNET.ORG, and Shelley Lewis, Executive Producer of Need to Know, spoke with THIRTEEN about this exciting new initiative. Need to Know offers an innovative approach to news reporting, fully integrating the broadcast and website. What inspired you to create the series? stephen segaller: We wanted to create a nnott newsmagazine that is weekly, topical and inherits the h Si depth and experience of our award-winning series like osep : J Wide Angle and Exposé, but also offers something otos h P entirely new in online journalism. The result is Need to Know, a broadcast and Web destination that SEGALLER reinforces the intelligence and substance expected / S i from public media. LEW thirteen.org 1 Describe the relationship between the Shelley, you’ve enjoyed an eclectic TV show and the website. career in network news. What attracted Shelley lewiS: They’re one and the you to public media? same. We don’t think of it as a website SL: The idea of creating a new kind with a TV show or a TV show with a of journalism that is both Web- and website. -

West Islip Public Library

CHILDREN'S TITLES (including Parent Collection) - as of January 1, 2013 NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a firefighter (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a zoo (CC) G African cats (SDH) PG Agent Cody Banks 2: destination London (CC) PG Alabama moon G Aladdin (2v) (CC) G Aladdin: the Return of Jafar (CC) PG Alex Rider: Operation stormbreaker (CC) NRA Alexander Graham Bell PG Alice in wonderland (2010-Johnny Depp) (SDH) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (CC) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (SDH) (2010 release) PG Aliens in the attic (SDH) NRA All aboard America (CC) NRA All about airplanes and flying machines NRA All about big red fire engines/All about construction NRA All about dinosaurs (CC) NRA All about dinosaurs/All about horses NRA All about earthquakes (CC) NRA All about electricity (CC) NRA All about endangered & extinct animals (CC) NRA All about fish (CC) NRA All about -

Focus Units in Literature: a Handbook for Elementary School Teachers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 247 608 CS 208 552 AUTHOR Moss, Joy F. TITLE Focus Units in Literature: A Handbook for Elementary School Teachers. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English,Urbana, Ill. y REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1756-2 PUB DATE 84 NOTE 245p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English,1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 17562, $13.00 nonmember, $10.00 member). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) Books (010) Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Literature; Content Area Reading;Content Area Writing; Curriculum Development; Curriculum Guides; Elementary Education; *LanguageArts; *Literature Appreciation; Models; PictureBooks; Reading Materials; Teaching Guides; *Unitsof Study ABSTRACT Intended as a guide for elementary schoolteachers to assist them in preparing and implementing specificliterature units or in de7eloping more long-term literatureprograms, this book contains 13 focus units. After defininga focus unit as an instructional sequence in which literatute isused both as a rich natural resource for developing language and thinkingskills and as the starting point for diverse reading and writingexperiences, the first chapter of the book describes the basiccomponents of a focus unit model. The second chapter identifiesthe theoretical foundations of this model, and the third chapterpresents seven categories of questions used in the focus unitsto guide comprehension and composition or narrative. The remaining 14chapters provide examples of the model as translated into classroom practice,each including a lesson plan for development,a description of its implementation, and a bibliography of texts. The units cover the following subjects:(1) animals in literature, (2) the works ofauthors Roger Duvoisin and Jay Williams, (3) the world aroundus,(4) literature around the world, (5) themes in literature, and (6)fantasy.