Copper River Subsistence Evaluation 2000 and Traditional Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crary-Henderson Collection, B1962.001

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Mary Langdon, Volunteer, and Sara Piasecki, Archivist TITLE: Crary-Henderson Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1962.001, B1962.001A OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1885-1930 Extent: 19.25 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): Will Crary; Nan Henderson; Phinney S. Hunt; Miles Bros.; Lyman; George C. Cantwell; Johnson; L. G. Robertson; Lillie N. Gordon; John E. Worden; W. A. Henderson; H. Schultz; Merl LaVoy; Guy F. Cameron; Eric A. Hegg Administrative/Biographical History: The Crary and Henderson Families lived and worked in the Valdez area during the boom times of the early 1900s. William Halbrook Crary was a prospector and newspaper man born in the 1870s (may be 1873 or 1876). William and his brother Carl N. Crary came to Valdez in 1898. Will was a member of the prospecting party of the Arctic Mining Company; Carl was the captain of the association. The Company staked the “California Placer Claim” on Slate Creek and worked outside of Valdez on the claim. Slate Creek is a tributary of the Chitina River, in the Chistochina District of the Copper River Basin. Will Crary was the first townsite trustee for Valdez. Carl later worked in the pharmaceutical field in Valdez and was also the postmaster. Will married schoolteacher Nan Fitch in Valdez in 1906. Carl died of cancer in 1927 in Portland, Oregon. -

1998 Fishing in Washington Regulations Pamphlet

STATE OF WASHINGTON 19981998 pamphletpamphlet editionedition FISHINGFISHING ININ WASHINGTONWASHINGTON Effective from May 1, 1998, to April 30, 1999, both dates inclusive. Contents INFORMATION Commission and Director Message .... 4 Information Phone Numbers .................................... 6 How to use this pamphlet ..................... 7 ? page 6 GENERAL RULES License Information .............................. 8 License Requirements ......................... 9 License & General Rules Definitions ...................................... 10-11 General Rules ................................ 12-13 page 8 MARINE AREA RULES Marine Area Rules ............................... 14 Marine Area Rules Marine Area Map and Definitions ........ 15 Marine Area Rules & Maps............. 17-39 Salmon ID Pictures ............................. 16 page 17 Selected Marine Fish ID Pictures ........ 40 SHELLFISH/SEAWEED RULES Shellfish/Seaweed Rules Shellfish/Seaweed General Rules ...... 41 Shellfish ID Pictures ............................ 42 page 41 Shellfish/Seaweed Rules .............. 43-51 FRESHWATER RULES Statewide General Statewide Freshwater Rules.......... 52-54 Freshwater Rules page 52 SPECIAL RULES Westside Rivers ............................. 55-85 Selected Game Fish ID Pictures.... 61-62 Special Rules W SPECIAL RULES Westside Rivers page 55 Westside Lakes ............................. 86-96 Westside Lakes Access Areas ........... 96 W Special Rules SPECIAL RULES Eastside Rivers ............................ 97-108 Westside Lakes page 85 Eastside -

The Yukon River Sub-District 5A Test Fish Wheel Project. 03-038. Final

U.S Fish and Wildlife Service Office of Subsistence Management Fisheries Resource Monitoring Program The Yukon River Sub-district 5A Test Fish Wheel Project Final Report for Study 03-038 Bill Fliris P.O. Box 169, Tanana, Alaska 99777 David Daum U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 101 12th Avenue, Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 February 2004 1 Title: The Yukon River Sub-district 5A Test Fish Wheel Project Study Number: 03-038 Investigators Affiliations: Bill Fliris, Tanana resident since 1973, project operator since 1993. David Daum, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fairbanks. Geographic Area: Yukon River (Sub-district 5A), river-mile 695 Information Type: Stock Status and Trends Issue Addressed: Run timing and relative abundance of Tanana River salmon stocks, 2003. Study Cost: $32,850 Study Duration: June 14 to September 19, 2003. Abstract: The Y-5A Test Fishwheel Project operated from June 14 to September 19 in 2003. Data were collected for Chinook, summer chum, fall chum and coho salmon entering the Tanana River. Video capture equipment was used throughout the season as the primary method of data collection. Key Words: Alaska, catch patterns, Chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, chum salmon, Oncorhynchus keta, coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch, migration timing, Tanana River, video capture, Yukon River. Project Data: Description - Data for this project are daily counts of all Tanana River salmon species caught by the fish wheel. Format – Catch-Per-Unit-Effort. Custodians - The Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Fairbanks, The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fairbanks, Bill Fliris, Tanana. Availability – Access to data available upon request to the custodians. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 155/Monday, August 12, 2019

39744 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 155 / Monday, August 12, 2019 / Rules and Regulations This final regulatory action will not DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE (907) 743–9461 or thomas.whitford@ have a significant economic impact on usda.gov. Forest Service a small entity once it receives a grant SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: because it would be able to meet the costs of compliance using the funds 36 CFR Part 242 Background provided under this program. Under Title VIII of the Alaska DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Intergovernmental Review: This National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) (16 U.S.C. 3111–3126), program is subject to Executive Order Fish and Wildlife Service 12372 and the regulations in 34 CFR the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture (Secretaries) part 79. One of the objectives of the 50 CFR Part 100 Executive order is to foster an jointly implement the Federal intergovernmental partnership and a [Docket No. FWS–R7–SM–2017–0096; Subsistence Management Program. This program provides a preference for take strengthened federalism. The Executive FXFR13350700640–190–FF07J00000; FBMS of fish and wildlife resources for order relies on processes developed by #4500133004] subsistence uses on Federal public State and local governments for RIN 1018–BC06 lands and waters in Alaska. The coordination and review of proposed Secretaries published temporary Federal financial assistance. Subsistence Management Regulations regulations to carry out this program in This document provides early for Public Lands in Alaska—2019–20 the Federal Register on June 29, 1990 notification of our specific plans and and 2020–21 Subsistence Taking of (55 FR 27114), and published final actions for this program. -

United Cook Inlet Drift Association 43961 K-Beach Road, Suite E

United Cook Inlet Drift Association 43961 K-Beach Road, Suite E. Soldotna, Alaska 99669.(907) 260-9436. fax (907) 260-9438 • [email protected] • December 16, 2011 Mr. Eric C. Schwaab Assistant Administrator for Fisheries National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 1315 East West Highway Room 14636 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Dear Mr. Schwaab: Thank you, again, for our recent teleconference. We appreciated not only the opportunity to-expre·ss-our-cnrrc-errrs-to-you-;-but-also your clear interest in tn-=-e +-is=s=u-=:es=---------- related to salmon management in Alaska. We are writing this letter to follow up on a couple of issues raised during that call. Our comments here are directed at the part of the Salmon Fisheries Management Plan (FMP) Amendment 12 that excludes the three historic net fisheries in the West Area from Federal oversight. As you know, the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council (NPFMC) decided last week to adopt provisions to eliminate these areas from the Fhd:P The stakeholders in the East A..rea ha:ve expressed that the status quo is acceptable to them and we respect their opinion. First, we wanted to elaborate on our concerns regarding the lack of stakeholder involvement. As we said during the teleconference, we have been mostly excluded from direct participation in the NPFMC' s current salmon FMP review. What we mean is that at no point during this process has the fishing community of Cook Inlet - fishermen, fish processors-or-local community-leaders=-been ·allowed-to-participate-in-developing the-- amendments. One of the core building blocks of decision-making under the Magnuson Stevens Act (MSA) is to directly involve.stakeholders in crafting solutions to fishery related problems. -

Forest Health Conditions in Alaska 2020

Forest Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Alaska Region | R10-PR-046 | April 2021 Forest Health Conditions in Alaska - 2020 A Forest Health Protection Report U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, State & Private Forestry, Alaska Region Karl Dalla Rosa, Acting Director for State & Private Forestry, 1220 SW Third Avenue, Portland, OR 97204, [email protected] Michael Shephard, Deputy Director State & Private Forestry, 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501, [email protected] Jason Anderson, Acting Deputy Director State & Private Forestry, 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501, [email protected] Alaska Forest Health Specialists Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, http://www.fs.fed.us/r10/spf/fhp/ Anchorage, Southcentral Field Office 161 East 1st Avenue, Door 8, Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: (907) 743-9451 Fax: (907) 743-9479 Betty Charnon, Invasive Plants, FHM, Pesticides, [email protected]; Jessie Moan, Entomologist, [email protected]; Steve Swenson, Biological Science Technician, [email protected] Fairbanks, Interior Field Office 3700 Airport Way, Fairbanks, AK 99709 Phone: (907) 451-2799, Fax: (907) 451-2690 Sydney Brannoch, Entomologist, [email protected]; Garret Dubois, Biological Science Technician, [email protected]; Lori Winton, Plant Pathologist, [email protected] Juneau, Southeast Field Office 11175 Auke Lake Way, Juneau, AK 99801 Phone: (907) 586-8811; Fax: (907) 586-7848 Isaac Dell, Biological Scientist, [email protected]; Elizabeth Graham, Entomologist, [email protected]; Karen Hutten, Aerial Survey Program Manager, [email protected]; Robin Mulvey, Plant Pathologist, [email protected] State of Alaska, Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry 550 W 7th Avenue, Suite 1450, Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: (907) 269-8460; Fax: (907) 269-8931 Jason Moan, Forest Health Program Coordinator, [email protected]; Martin Schoofs, Forest Health Forester, [email protected] University of Alaska Fairbanks Cooperative Extension Service 219 E. -

Navigating Troubled Waters a History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve Navigating Troubled Waters A History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska Author: James Mackovjak National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve “If people want both to preserve the sea and extract the full benefit from it, they must now moderate their demands and structure them. They must put aside ideas of the sea’s immensity and power, and instead take stewardship of the ocean, with all the privileges and responsibilities that implies.” —The Economist, 1998 Navigating Troubled Waters: Part 1: A History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska Part 2: Hoonah’s “Million Dollar Fleet” U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve Gustavus, Alaska Author: James Mackovjak 2010 Front cover: Duke Rothwell’s Dungeness crab vessel Adeline in Bartlett Cove, ca. 1970 (courtesy Charles V. Yanda) Back cover: Detail, Bartlett Cove waters, ca. 1970 (courtesy Charles V. Yanda) Dedication This book is dedicated to Bob Howe, who was superintendent of Glacier Bay National Monument from 1966 until 1975 and a great friend of the author. Bob’s enthusiasm for Glacier Bay and Alaska were an inspiration to all who had the good fortune to know him. Part 1: A History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska Table of Contents List of Tables vi Preface vii Foreword ix Author’s Note xi Stylistic Notes and Other Details xii Chapter 1: Early Fishing and Fish Processing in Glacier Bay 1 Physical Setting 1 Native Fishing 1 The Coming of Industrial Fishing: Sockeye Salmon Attract Salters and Cannerymen to Glacier Bay 4 Unnamed Saltery at Bartlett Cove 4 Bartlett Bay Packing Co. -

Vegetation Study of Alaska's Richardson Highway: Identification

Alaska Department of Transportation & Public Facilities Research & Technology Transfer ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Vegetation Study of Alaska’s Richardson Highway: Identification of Plant Communities and Assessment of Control Strategies Prepared by: Andrew Nolen, Agronomist Donald Ross, Agronomist Alaska Plant Materials Center Division of Agriculture Department of Natural Resources November, 2006 Prepared for: Alaska Department of Transportation Statewide Research Office 3132 Channel Drive Juneau, AK 99801-7898 FHWA-AK-RD-06-04 Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document. Quality Assurance Statement The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) provides high-quality information to serve Government, industry, and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. FHWA periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. Author’s Disclaimer Opinions and conclusions expressed or implied in the report are those of the author. They are not necessarily those of the Alaska DOT&PF or funding agencies. Form approved OMB No. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Public reporting for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. -

A Laska a Laska

Goto alaskamotobook.com to find detailed maps and routes, travel links, and to order the print book or ebook! The Adventurous The Adventurous Motorcyclist’s Guide to Motorcyclist’s Guide to Alaska Motorcyclist’s The Adventurous Guide to Guide Alaska Alaska AlaskaAlaska Put one of the most knowledgable motorcycle tour guides in Alaska in your pocket with this witty, fun book that brings to life the best roads and off-beat destinations in the state. This colorful guide lists all the road routes in Alaska with recommended dirt road excursions past mines, mountains and streams. The book includes ideal itineraries, the most interesting side roads, and great places to sleep, eat, and get off your bike to sightsee. Gear suggestions, motorcycle transport options, camping tips, and how to incorporate the Marine Highway System into your trip are also part of the package. The content focuses on the Alaska dirt and paved highways, but also includes the Canadian highways of interest as well as the Alaska Highway from Dawson Creek, British Columbia Klancher to Delta Junction, Alaska. Created by author Lee Klancher and long-time Alaskan motorcycle tour guide Phil Freeman, this obsessively-researched book combines unsurpassed detail on the best with backroads in Alaska with first-hand recommendations for the best hotels, cabins, Freeman restaurants, and micro-breweries from a guide who has visited every corner of America’s wildest state. ISBN 978-0-9829131-2-3 Lee Klancher $29.95 with 978-0-9829131-2-3 octanepress.com Printed in China 7809829 913123 -

Yukon River Salmon Age, Sex, and Length Database Error Checking and Finalization

Regional Information Report No. 3A06-08 Yukon River Salmon Age, Sex, and Length Database Error Checking and Finalization Final Report for Project URE 17N-05 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service by Holly A. Krenz and Linda K. Brannian December 2006 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, Special Publications and the Division of Commercial Fisheries Regional Reports. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Administrative fork length FL deciliter dL Code AAC mideye-to-fork MEF gram g all commonly accepted mideye-to-tail-fork METF hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., standard length SL kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. total length TL kilometer km all commonly accepted liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., Mathematics, statistics meter m R.N., etc. all standard mathematical milliliter mL at @ signs, symbols and millimeter mm compass directions: abbreviations east E alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) north N base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s south S catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft west W coefficient of variation CV gallon gal copyright © common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) inch in corporate suffixes: confidence interval CI mile mi Company Co. -

Chapter 6 Passive Capture Techniques

Chapter 6 Passive Capture Techniques WAYNE A. HUBERT, KEVIN L. POPE, AND JOHN M. DETTMERS 6.1 INTRODUCTION Passive capture techniques involve the capture of fishes or other aquatic animals by en- tanglement, entrapment, or angling devices that are not actively moved by humans or ma- chines while the organisms are being captured (Lagler 1978). The behavior and movements of the animals themselves result in their capture. The techniques used in passive sampling of fish populations are similar to those used for food gathering over the centuries. Nets and traps have been widely used among various cultures, and many of the currently applied techniques were used by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans (Alverson 1963). Based on their mode of capture, passive sampling devices can be divided into three groups: (1) entanglement, (2) entrapment, and (3) angling gears. Entanglement devices capture fish by holding them ensnared or tangled in webbing or mesh made of natural or artificial materials. Gill nets and trammel nets are examples of entanglement gears (Figure 6.1). Entrapment de- vices capture organisms that enter an enclosed area through one or more funnel- or V-shaped openings that hinder escape after entrance. Hoop nets, trap nets, and pot devices are examples of entrapment gears (Figures 6.2 and 6.3). Angling devices capture fish with a baited hook and line. Trotlines and longlines are examples of passive angling gears (Figure 6.4). Gear selectivity and gear efficiency are important considerations with respect to passive sam- pling devices. Often these terms are used interchangeably, but they have different, specific defi- nitions. -

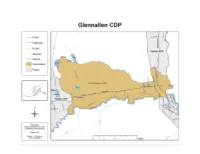

AK FED CARES Glenn Boundry Map.Pdf

GLENNALLEN AREA BOUNDARIES: WEST: From the Northwest corner boundary begins at Island Lake… approximately 3 miles south of the southern tip of the Island Lake, the boundary follows the Tolsona Creek. It follows the creek across the Glenn Highway to the Tazlina River. GOING EAST. From the South Western corner, the boundary follows the Tazlina River… it crosses Moose Creek and travels directly East from Moose Creek to the bottom of Simpson hill. (It does not follow the Tazlina River once it intersects with Moose Creek. The boundary curves alongside the mountain ending at the Richardson Highway at the bottom of Simpson hill (south)) The boundary does not include what used to be called the Tazlina Trailer court. Heading North: From the Bottom of Simpson Hill, the boundary includes the west side of the Richardson Highway until the top of Simpson Hill. At the top of Simpson Hill, the boundary then becomes the Copper River. It follows the Copper River until Dry Creek. It follows Dry Creek as it winds its way Northwest until it crosses with the Richardson Highway. Once it crosses the Richardson Highway it follows the Creek until 22 Alaska Pipeline road. This boundary stops at the end of the APL 22 road. Heading South: The boundary heads directly south from the end of the APL 22 road (Approximately 2.5 miles) This path is the path of the pipeline. At approximately 1 mile north of the Glenn Highway the boundary then goes in a perpendicular line (WEST) until it hits Moose Creek. HEADING NORTHWEST: The border then moves in a Northwest line as it follows Moose Creek all the way to Tolsona Lake.