Lecture 16: Evolution of Low-Mass Stars Readings: 21-1, 21-2, 22-1, 22-3 and 22-4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collapsars As a Major Source of R-Process Elements

Collapsars as a major source of r-process elements Daniel M. Siegel1;2;3;4;5, Jennifer Barnes1;2;5 & Brian D. Metzger1;2 1Department of Physics, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA 2Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA 3Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 4Department of Physics, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada 5NASA Einstein Fellow The production of elements by rapid neutron capture (r-process) in neutron-star mergers is expected theoretically and is supported by multimessenger observations1–3 of gravitational- wave event GW170817: this production route is in principle sufficient to account for most of the r-process elements in the Universe4. Analysis of the kilonova that accompanied GW170817 identified5, 6 delayed outflows from a remnant accretion disk formed around the newly born black hole7–10 as the dominant source of heavy r-process material from that event9, 11. Sim- ilar accretion disks are expected to form in collapsars (the supernova-triggering collapse of rapidly rotating massive stars), which have previously been speculated to produce r-process elements12, 13. Recent observations of stars rich in such elements in the dwarf galaxy Retic- arXiv:1810.00098v2 [astro-ph.HE] 14 Aug 2020 ulum II14, as well as the Galactic chemical enrichment of europium relative to iron over longer timescales15, 16, are more consistent with rare supernovae acting at low stellar metal- licities than with neutron-star mergers. Here we report simulations that show that collapsar accretion disks yield sufficient r-process elements to explain observed abundances in the Uni- 1 verse. Although these supernovae are rarer than neutron- star mergers, the larger amount of material ejected per event compensates for the lower rate of occurrence. -

The Variable Stars and Blue Horizontal Branch of the Metal-Rich Globular Cluster NGC 6441

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The Variable Stars and Blue Horizontal Branch of the Metal-Rich Globular Cluster NGC 6441 Andrew C. Layden1;2 Physics & Astronomy Dept., Bowling Green State Univ., Bowling Green, OH 43403, U.S.A. Laura A. Ritter Department of Astronomy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1090, U.S.A. Douglas L. Welch1,TracyM.A.Webb1 Department of Physics & Astronomy, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4M1, Canada ABSTRACT We present time-series VI photometry of the metal-rich ([Fe=H]= 0:53) globular − cluster NGC 6441. Our color-magnitude diagram shows that the extended blue horizontal branch seen in Hubble Space Telescope data exists in the outermost reaches of the cluster. About 17% of the horizontal branch stars lie blueward and brightward of the red clump. The red clump itself slopes nearly parallel to the reddening vector. A component of this slope is due to differential reddening, but part is intrinsic. The blue horizontal branch stars are more centrally concentrated than the red clump stars, suggesting mass segregation and a possible binary origin for the blue horizontal branch stars. We have discovered 50 new variable stars near NGC 6441, among ∼ them eight or more RR Lyrae stars which are highly-probable cluster members. Comprehensive period searches over the range 0.2–1.0 days yielded unusually long periods (0.5–0.9 days) for the fundamental pulsators compared with field RR Lyrae of the same metallicity. Three similar long-period RR Lyrae are known in other metal-rich globulars. -

White Dwarfs

Chandra X-Ray Observatory X-Ray Astronomy Field Guide White Dwarfs White dwarfs are among the dimmest stars in the universe. Even so, they have commanded the attention of astronomers ever since the first white dwarf was observed by optical telescopes in the middle of the 19th century. One reason for this interest is that white dwarfs represent an intriguing state of matter; another reason is that most stars, including our sun, will become white dwarfs when they reach their final, burnt-out collapsed state. A star experiences an energy crisis and its core collapses when the star's basic, non-renewable energy source - hydrogen - is used up. A shell of hydrogen on the edge of the collapsed core will be compressed and heated. The nuclear fusion of the hydrogen in the shell will produce a new surge of power that will cause the outer layers of the star to expand until it has a diameter a hundred times its present value. This is called the "red giant" phase of a star's existence. A hundred million years after the red giant phase all of the star's available energy resources will be used up. The exhausted red giant will puff off its outer layer leaving behind a hot core. This hot core is called a Wolf-Rayet type star after the astronomers who first identified these objects. This star has a surface temperature of about 50,000 degrees Celsius and is A composite furiously boiling off its outer layers in a "fast" wind traveling 6 million image of the kilometers per hour. -

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants There is a large variety of stellar models which have a distinct core – envelope structure. While any main sequence star, or any white dwarf, may be well approximated with a single polytropic model, the stars with the core – envelope structure may be approximated with a composite polytrope: one for the core, another for the envelope, with a very large difference in the “K” constants between the two. This is a consequence of a very large difference in the specific entropies between the core and the envelope. The original reason for the difference is due to a jump in chemical composition. For example, the core may have no hydrogen, and mostly helium, while the envelope may be hydrogen rich. As a result, there is a nuclear burning shell at the bottom of the envelope; hydrogen burning shell in our example. The heat generated in the shell is diffusing out with radiation, and keeps the entropy very high throughout the envelope. The core – envelope structure is most pronounced when the core is degenerate, and its specific entropy near zero. It is supported against its own gravity with the non-thermal pressure of degenerate electron gas, while all stellar luminosity, and all entropy for the envelope, are provided by the shell source. A common property of stars with well developed core – envelope structure is not only a very large jump in specific entropy but also a very large difference in pressure between the center, Pc, the shell, Psh, and the photosphere, Pph. Of course, the two characteristics are closely related to each other. -

(GK 1; Pr 1.1, 1.2; Po 1) What Is a Star?

1) Observed properties of stars. (GK 1; Pr 1.1, 1.2; Po 1) What is a star? Why study stars? The sun Age of the sun Nearby stars and distribution in the galaxy Populations of stars Clusters of stars Distances and characterization of stars Luminosity and flux Magnitudes Parallax Standard candles Cepheid variables SN Ia 2) The HR diagram and stellar masses (GK 2; Pr 1.4; Po 1) Colors of stars B-V Blackbody emission HR Diagram Interpretation of HR diagram stellar radii kinds of stars red giants white dwarfs planetary nebulae AGB stars Cepheids Horizontal branch evolutionary sequence turn off mass and ages Masses from binaries Circular orbits solution General solution Spectroscopic binaries Eclipsing spectroscopic binaries Empirical mass luminosity relation 3) Spectroscopy and abundances (GK 1; Pr 2) Stellar spectra OBFGKM Atomic physics H atom others Spectral types Temperature and spectra Boltzmann equation for levels Saha equation for ionization ionization stages Rotation Stellar Abundances More about ionization stages, e.g. Ca and H Meteorite abundances Standard solar set Abundances in other stars and metallicity 4) Hydrostatic balance, Virial theorem, and time scales (GK 3,4; Pr 1.3, 2; Po 2,8) Assumptions - most of the time Fully ionized gas except very near surface where partially ionized Spherical symmetry Broken by e.g., convection, rotation, magnetic fields, explosion, instabilities, etc Makes equations a lot easier Limits on rotation and magnetic fields Homogeneous composition at birth Isolation (drop this later in course) Thermal -

The Sun, Yellow Dwarf Star at the Heart of the Solar System NASA.Gov, Adapted by Newsela Staff

Name: ______________________________ Period: ______ Date: _____________ Article of the Week Directions: Read the following article carefully and annotate. You need to include at least 1 annotation per paragraph. Be sure to include all of the following in your total annotations. Annotation = Marking the Text + A Note of Explanation 1. Great Idea or Point – Write why you think it is a good idea or point – ! 2. Confusing Point or Idea – Write a question to ask that might help you understand – ? 3. Unknown Word or Phrase – Circle the unknown word or phrase, then write what you think it might mean based on context clues or your word knowledge – 4. A Question You Have – Write a question you have about something in the text – ?? 5. Summary – In a few sentences, write a summary of the paragraph, section, or passage – # The sun, yellow dwarf star at the heart of the solar system NASA.gov, adapted by Newsela staff Picture and Caption ___________________________ ___________________________ ___________________________ Paragraph #1 ___________________________ ___________________________ This image shows an enormous eruption of solar material, called a coronal mass ejection, spreading out into space, captured by NASA's Solar Dynamics ___________________________ Observatory on January 8, 2002. Paragraph #2 Para #1 The sun is a hot ball made of glowing gases and is a type ___________________________ of star known as a yellow dwarf. It is at the heart of our solar system. ___________________________ Para #2 The solar system consists of everything that orbits the ___________________________ sun. The sun's gravity holds the solar system together, by keeping everything from planets to bits of dust in its orbit. -

Brown Dwarf: White Dwarf: Hertzsprung -Russell Diagram (H-R

Types of Stars Spectral Classifications: Based on the luminosity and effective temperature , the stars are categorized depending upon their positions in the HR diagram. Hertzsprung -Russell Diagram (H-R Diagram) : 1. The H-R Diagram is a graphical tool that astronomers use to classify stars according to their luminosity (i.e. brightness), spectral type, color, temperature and evolutionary stage. 2. HR diagram is a plot of luminosity of stars versus its effective temperature. 3. Most of the stars occupy the region in the diagram along the line called the main sequence. During that stage stars are fusing hydrogen in their cores. Various Types of Stars Brown Dwarf: White Dwarf: Brown dwarfs are sub-stellar objects After a star like the sun exhausts its nuclear that are not massive enough to sustain fuel, it loses its outer layer as a "planetary nuclear fusion processes. nebula" and leaves behind the remnant "white Since, comparatively they are very cold dwarf" core. objects, it is difficult to detect them. Stars with initial masses Now there are ongoing efforts to study M < 8Msun will end as white dwarfs. them in infrared wavelengths. A typical white dwarf is about the size of the This picture shows a brown dwarf around Earth. a star HD3651 located 36Ly away in It is very dense and hot. A spoonful of white constellation of Pisces. dwarf material on Earth would weigh as much as First directly detected Brown Dwarf HD 3651B. few tons. Image by: ESO The image is of Helix nebula towards constellation of Aquarius hosts a White Dwarf Helix Nebula 6500Ly away. -

Stars IV Stellar Evolution Attendance Quiz

Stars IV Stellar Evolution Attendance Quiz Are you here today? Here! (a) yes (b) no (c) my views are evolving on the subject Today’s Topics Stellar Evolution • An alien visits Earth for a day • A star’s mass controls its fate • Low-mass stellar evolution (M < 2 M) • Intermediate and high-mass stellar evolution (2 M < M < 8 M; M > 8 M) • Novae, Type I Supernovae, Type II Supernovae An Alien Visits for a Day • Suppose an alien visited the Earth for a day • What would it make of humans? • It might think that there were 4 separate species • A small creature that makes a lot of noise and leaks liquids • A somewhat larger, very energetic creature • A large, slow-witted creature • A smaller, wrinkled creature • Or, it might decide that there is one species and that these different creatures form an evolutionary sequence (baby, child, adult, old person) Stellar Evolution • Astronomers study stars in much the same way • Stars come in many varieties, and change over times much longer than a human lifetime (with some spectacular exceptions!) • How do we know they evolve? • We study stellar properties, and use our knowledge of physics to construct models and draw conclusions about stars that lead to an evolutionary sequence • As with stellar structure, the mass of a star determines its evolution and eventual fate A Star’s Mass Determines its Fate • How does mass control a star’s evolution and fate? • A main sequence star with higher mass has • Higher central pressure • Higher fusion rate • Higher luminosity • Shorter main sequence lifetime • Larger -

The Potential of Planets Orbiting Red Dwarf Stars to Support Oxygenic Photosynthesis and Complex Life

1 The Potential of Planets Orbiting Red Dwarf Stars to Support Oxygenic Photosynthesis and Complex Life Joseph Gale1 and Amri Wandel2 The Institute of Life Sciences1and The Racach Institute of Physics2, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 91904, Israel. [email protected] [email protected] Accepted for publication in the International Journal of Astrobiology Abstract We review and reassess the latest findings on the existence of extra-solar system planets and their potential of having environmental conditions that could support Earth-like life. Within the last two decades, the multi-millennial question of the existence of extra-Solar- system planets has been resolved with the discovery of numerous planets orbiting nearby stars, many of which are Earth-sized (and some even with moderate surface temperatures). Of particular interest in our search for clement conditions for extra-solar system life are planets orbiting Red Dwarf (RD) stars, the most numerous stellar type in the Milky Way galaxy. We show that including RDs as potential life supporting host stars could increase the probability of finding biotic planets by a factor of up to a thousand, and reduce the estimate of the distance to our nearest biotic neighbor by up to 10. We argue that multiple star systems need to be taken into account when discussing habitability and the abundance of biotic exoplanets, in particular binaries of which one or both members are RDs. Early considerations indicated that conditions on RD planets would be inimical to life, as their Habitable Zones (where liquid water could exist) would be so close as to make planets tidally locked to their star. -

Chapter 16 the Sun and Stars

Chapter 16 The Sun and Stars Stargazing is an awe-inspiring way to enjoy the night sky, but humans can learn only so much about stars from our position on Earth. The Hubble Space Telescope is a school-bus-size telescope that orbits Earth every 97 minutes at an altitude of 353 miles and a speed of about 17,500 miles per hour. The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) transmits images and data from space to computers on Earth. In fact, HST sends enough data back to Earth each week to fill 3,600 feet of books on a shelf. Scientists store the data on special disks. In January 2006, HST captured images of the Orion Nebula, a huge area where stars are being formed. HST’s detailed images revealed over 3,000 stars that were never seen before. Information from the Hubble will help scientists understand more about how stars form. In this chapter, you will learn all about the star of our solar system, the sun, and about the characteristics of other stars. 1. Why do stars shine? 2. What kinds of stars are there? 3. How are stars formed, and do any other stars have planets? 16.1 The Sun and the Stars What are stars? Where did they come from? How long do they last? During most of the star - an enormous hot ball of gas day, we see only one star, the sun, which is 150 million kilometers away. On a clear held together by gravity which night, about 6,000 stars can be seen without a telescope. -

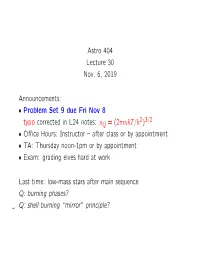

Astro 404 Lecture 30 Nov. 6, 2019 Announcements

Astro 404 Lecture 30 Nov. 6, 2019 Announcements: • Problem Set 9 due Fri Nov 8 2 3/2 typo corrected in L24 notes: nQ = (2πmkT/h ) • Office Hours: Instructor – after class or by appointment • TA: Thursday noon-1pm or by appointment • Exam: grading elves hard at work Last time: low-mass stars after main sequence Q: burning phases? 1 Q: shell burning “mirror” principle? Low-Mass Stars After Main Sequence unburnt H ⋆ helium core contracts H He H burning in shell around core He outer layers expand → red giant “mirror” effect of shell burning: • core contraction, envelope expansion • total gravitational potential energy Ω roughly conserved core becomes more tightly bound, envelope less bound ⋆ helium ignition degenerate core unburnt H H He runaway burning: helium flash inert He → 12 He C+O 2 then core helium burning 3α C and shell H burning “horizontal branch” star unburnt H H He ⋆ for solar mass stars: after CO core forms inert He He C • helium shell burning begins inert C • hydrogen shell burning continues Q: star path on HR diagram during these phases? 3 Low-Mass Post-Main-Sequence: HR Diagram ⋆ H shell burning ↔ red giant ⋆ He flash marks “tip of the red giant branch” ⋆ core He fusion ↔ horizontal branch ⋆ He + H shell burning ↔ asymptotic giant branch asymptotic giant branch H+He shell burn He flash core He burn L main sequence horizontal branch red giant branch H shell burning Sun Luminosity 4 Temperature T iClicker Poll: AGB Star Intershell Region in AGB phase: burning in two shells, no core fusion unburnt H H He inert He He C Vote your conscience–all -

Hydrogen-Deficient Stars

Hydrogen-Deficient Stars ASP Conference Series, Vol. 391, c 2008 K. Werner and T. Rauch, eds. Hydrogen-Deficient Stars: An Introduction C. Simon Jeffery Armagh Observatory, College Hill, Armagh BT61 9DG, N. Ireland, UK Abstract. We describe the discovery, classification and statistics of hydrogen- deficient stars in the Galaxy and beyond. The stars are divided into (i) massive / young star evolution, (ii) low-mass supergiants, (iii) hot subdwarfs, (iv) cen- tral stars of planetary nebulae, and (v) white dwarfs. We introduce some of the challenges presented by these stars for understanding stellar structure and evolution. 1. Beginning Our science begins with a young woman from Dundee in Scotland. The brilliant Williamina Fleming had found herself in the employment of Pickering at the Harvard Observatory where she noted that “the spectrum of υ Sgr is remarkable since the hydrogen lines are very faint and of the same intensity as the additional dark lines” (Fleming 1891). Other stars, well-known at the time, later turned out also to have an unusual hydrogen signature; the spectacular light variations of R CrB had been known for a century (Pigott 1797), while Wolf & Rayet (1867) had discovered their emission-line stars some forty years prior. It was fifteen years after Fleming’s discovery that Ludendorff (1906) observed Hγ to be completely absent from the spectrum of R CrB, while arguments about the hydrogen content of Wolf-Rayet stars continued late into the 20th century. Although these early observations pointed to something unusual in the spec- tra of a variety of stars, there was reluctance to accept (or even suggest) that hydrogen might be deficient.