Accountability and Control: the Politics of Privatisation in WA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seasons Greetings to List)

Everything you need to hit the trail! Seasons • 4WDriving Equipment • Cooking • Kayaks SUMMER 2008 • Backpacks • Fishing • Refrigeration & Coolers Greetings ISSUE#49 • Books, Maps & DVD’s • Gas Refills • Sleeping Bags RRP $6.00 • Camping Tables & Cupboards • Gazebos • Swags • Caravanning Equipment • Generators • Tents • Clothing for Summer & Winter • GPS Systems • Watersports s l e t t e u l m u n T • Bags • Headlamps • Portable Showers & Toilets N e w r f o r r i e n d s B i b b r a c k • Bait • Hiking Boots • Pumps t h e f o f t h e • Batteries • Hobie Kayaks & • Stretchers • Boating Accessories • Sunglasses • Compasses • Kayak Carts • Tackle & Tackle Boxes • Containers • Knives • Towels • Diving & Snorkelling Equipment • Lanterns • Fishing – Fly/Mosquitos The 10th Anniversary Finale • Fins • Lights • Reels • Masks • Masks • Rods • Footwear • Mats & Blow Up Beds • Tools • Hats • Nets • Torches Bibbulmun Track Foundation members receive 10% OFF* all recommended retail prices on Ranger Outdoors’ huge range of quality gear. 14 stores locally owned and operated located around Western Australia • www.rangeroutdoors.com.au Proudly Proud Sponsor BALCATTA Cnr Wanneroo Rd & Amelia Street 9344 7343 MANDURAH 65 Reserve Drive 9583 4800 Western Australian of the Bibbulmun Owned and Operated Track Foundation BENTLEY 1163 Albany Hwy (Cnr Bedford Street) 9356 5177 MIDLAND Midland Central (Cnr Clayton & Lloyd St) 9274 4044 OPEN ALL WEEKEND BUSSELTON Home Depot Strelly Street 9754 8500 MORLEY 129 Russell Street (Opp. Galleria Bus Station) 9375 5000 SUMMER -

Department of Lands.Pdf

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 16 September 2015] p6507b-6516a Mr Joe Francis; Ms Margaret Quirk EMERGENCY SERVICES LEVY Motion Resumed from 9 September on the following motion moved by Ms M.M. Quirk — That this house condemns the Barnett government for misappropriating funds collected by the emergency services levy for purely administrative purposes instead of for frontline emergency needs, and calls for a system of independent allocation of ESL funds to be implemented as recommended in the first Keelty inquiry. MR J.M. FRANCIS (Jandakot — Minister for Emergency Services) [5.40 pm]: I start by acknowledging members of the opposition who have spoken to this motion; I do not have a list of names with me, but I know the member for Armadale made a contribution last Wednesday before this motion was adjourned. I say from the start that obviously the government does not support the motion brought to the house by the shadow Minister for Emergency Services, the member for Girrawheen, and I will outline the reasons why. Firstly let me say that the wording of the motion — The ACTING SPEAKER (Mr I.M. Britza): Members, if you want to have a conversation, I ask you to leave the chamber, please. Mr J.M. FRANCIS: Firstly let me say that obviously the government will not support this motion and I will outline the reasons why. I do not mean to be provocative by saying this, but I would suggest that the motion is fairly harshly worded and, I would go so far as to say, pretty offensive to both the Fire and Emergency Services Commissioner and the staff of the Department of Fire and Emergency Services, purely through the use of the words “misappropriating funds”. -

P1226b-1231A Mr David Templeman; Ms Margaret Quirk; Mr Sean L'estrange

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 16 March 2016] p1226b-1231a Mr David Templeman; Ms Margaret Quirk; Mr Sean L'Estrange SENTENCE ADMINISTRATION AMENDMENT BILL 2016 Second Reading Resumed from 24 February. MR D.A. TEMPLEMAN (Mandurah) [7.25 pm]: I would like to speak to the motion before us on the notice paper, which is a private members’ bill, the Sentence Administration Amendment Bill 2016, that was introduced by the member for Butler. The ACTING SPEAKER (Mr P. Abetz): There are too many conversations happening all at once. The member for Mandurah has the call, so let us take our conversations outside or hush our voices a little. Thank you. Mr D.A. TEMPLEMAN: Earlier this year members would be aware that I tabled a substantial online petition signed by over 20 000 online petitioners and a petition that complied with standing orders of this place that was signed by two members of the public—Margaret and Ray Dodd. Margaret and Ray’s daughter Hayley went missing a number of years ago and she has never been found, and, of course, it is presumed that she met a tragic end. I do not want to talk about their case because it is before the court and I do not want to prejudice or have any negative impact on the proper procedures in this case. Margaret and Ray are like a number of parents and families in not only Western Australia but Australia generally who have loved ones, daughters or sons, who have gone missing—some who were murdered but their perpetrator has never been found or indeed the perpetrator has been tried for murder and been found guilty. -

The Official Magazine of the Uwa Politics Club October

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE UWA POLITICS CLUB OCTOBER 2018 I EDITION 1313 Published by the UWA Politics Club OUR SPONSORS We would like to acknowledge the support of our sponsors whose kind generosity allows us to help fund the operations of the club. 2018 Calendar Year Sponsors 2018/2019 Financial Year Sponsors Platinum Gold Hon. Charles Smith MLC Hon. Melissa Price MP Member for East Metropolitan Region Federal Member for Durack Hon. Sue Ellery MLC Hon. Roger Cook MLA Member for South Metropolitan Region Member for Kwinana Hon. Tjorn Sibma MLC Silver Member for North Metropolitan Region Alyssa Hayden MLA Member for Darling Range Gold Senator Linda Reynolds CSC Hon. Mark McGowan MLA Senator for Western Australia Member for Rockingham and Premier of Western Australia Silver Hon. Christian Porter MP Hon. Michael Mischin MLC Federal Member for Pearce Member for North Metropolitan Region Bronze Bronze Ben Morton MP Hon. Darren West MLC Federal Member for Tangney Member for the Agricultural Region Margaret Quirk MLA Senator Louise Pratt Member for Girrawheen Senator for Western Australia Jessica Shaw MLA Hon. Nick Goiran MLC Member for Swan Hills Member for South Metropolitan Region Tim Hammond Hon. Paul Papalia MLA CSC As the Federal Member for Perth Member for Wanbro Simon Millman MLA Member for Mount Lawley Hon. Stephen Dawson MLC Member for Mining and Pastoral Region 2 CONTENTS FROM THE PRESIDENT 5 FROM THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 8 OUR HISTORY 9 2018 REVIEWED 10 OUR CONTRIBUTORS 12 FEATURE: WHAT DOES THE AUSTRALIAN DREAM MEAN TO YOU? 14 TJORN -

P425b-431A Ms Margaret Quirk; Ms E.L

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 11 May 2021] p425b-431a Ms Margaret Quirk; Ms E.L. Hamilton ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Motion Resumed from 6 May on the following motion moved by Ms L. Dalton — That the following Address-in-Reply to His Excellency’s speech be agreed to — To His Excellency the Honourable Kim Beazley, AC, Governor of the State of Western Australia. May it please Your Excellency — We, the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of the State of Western Australia in Parliament assembled, beg to express loyalty to our Most Gracious Sovereign, and to thank Your Excellency for the speech you have been pleased to address to Parliament. MS M.M. QUIRK (Landsdale) [7.05 pm]: I start by acknowledging the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet today, the Whadjuk people of the great Noongar nation. I recognise their continuing connection to the land, water and community. I pay my respects to their elders, past, present and future, and I extend my respect to all the First Nations people throughout this great state. It is an enormous pleasure to also extend my welcome to the many new members in the chamber. That pleasure is magnified many times over, because those new members all belong to the WA Labor Party, and, even more of a bonus, there is a large number of women amongst this cohort. As Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the House of Representatives in the US, has famously said, “Maybe it takes a woman to clean house.” In their inaugural speeches, we heard an impressive array of life experiences from these new members. -

Report on the Investigation of Alleged Public Sector Misconduct at the City of Wanneroo.Pdf

CORRUPTION AND CRIME COMMISSION REPORT ON THE INVESTIGATION OF ALLEGED PUBLIC SECTOR MISCONDUCT AT THE CITY OF WANNEROO 3 December 2009 ISBN: 978 0 9805051 5 3 © 2009 Copyright in this work is held by the Corruption and Crime Commission. Division 3 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth) recognises that limited further use of this material can occur for the purposes of “fair dealing”, for example, study, research or criticism. Should you wish to make use of this material other than as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968 please write to the Corruption and Crime Commission at the postal address below. This report and further information about the Corruption and Crime Commission can be found on the Commission Website at www.ccc.wa.gov.au. Corruption and Crime Commission Postal Address PO Box 7667 Cloisters Square PERTH WA 6850 Telephone (08) 9215 4888 1800 809 000 (Toll Free for callers outside the Perth metropolitan area.) Facsimile (08) 9215 4884 Email [email protected] Office Hours 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Monday to Friday. CORRUPTION AND CRIME COMMISSION Mr Malcolm Peacock Mr Peter John McHugh Clerk of the Legislative Council Clerk of the Legislative Assembly Parliament House Parliament House Harvest Terrace Harvest Terrace PERTH WA 6000 PERTH WA 6000 Dear Mr Peacock Dear Mr McHugh As neither House of Parliament is presently sitting, in accordance with section 93 of the Corruption and Crime Commission Act 2003 (“the CCC Act”), the Commission hereby transmits to you a copy of the Corruption and Crime Commission Report on the Investigation of Alleged Public Sector Misconduct at the City of Wanneroo. -

Feminism, Politics and Women's Policy in Western Australia, 1972

Burning Down the House?: Feminism, Politics and Women’s Policy in Western Australia, 1972-1998 Jasmina Brankovich, BA (Hons) UWA This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia School of Humanities, Discipline of History 2007 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the constraints and options inherent in placing feminist demands on the state, the limits of such interventions, and the subjective, intimate understandings of feminism among agents who have aimed to change the state from within. First, I describe the central element of a „femocratic‟ policy machinery as a three-tiered network of politicians, public servants, and women in community organisations and political lobbies, who were agents of a particular brand of feminism. I focus on the formation of a women‟s information service, passage of equal opportunity legislation, and a legislative decriminalisation of early abortion, as case studies where these networks were most effective in engendering change. Second, the politics of the 1970s Perth women‟s movement shared a heritage of peculiarly Australian tradition of social liberalism, where the state intervened to equalise the unequal social order. The „feminism‟ articulated within the state was influenced by social liberalism, but was also configured and reconfigured according to the specific Western Australian political context. Third, the material obtained in interviews with women politicians and senior bureaucrats constituted the most important source of the women‟s understandings of the politically volatile arenas of public life in which they worked. In particular, insights gathered in this material underscored and reinforced the complexities of feminist involvement with the state and the fragile, contraditory nature of feminist gains. -

Annual Report

Political Finance Annual Report Report on the operation of Part VI of the Electoral Act 1907 for the period ended 30 June 2012 Hon. Peter Collier MLC Minister for Electoral Affairs Level 10 Dumas House 2 Havelock Street West Perth WA 6005 Dear Minister In accordance with section 175ZG of the Electoral Act 1907, I submit for your information and presentation to Parliament the report on the operation of Part VI of the Electoral Act 1907 for the period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. Yours sincerely Chris Avent A/ELECTORAL COMMISSIONER Political Finance Annual Report 2011–2012 | Western Australian Electoral Commission i Contents Executive Summary............................................................................................ 1 Appendix 1: Summary of disclosures through 2011–2012 ............................................. 1 2011─2012 Political finance disclosure schedule ............................................. 12 Recommendations to improve the operation of Part VI of the Act ...................... 2 Appendix 2: Summary of gifts and other income received by each political party................ 13 1.0 Issues and inconsistencies ........................................................................ 3 1.1 Overview ............................................................................................ 3 Appendix 3: 1.2 Receipts and electronic recordkeeping .............................................. 3 Gifts $2,100 or greater received by political parties ......................................... 14 1.3 Threshold for -

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 2

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 2 April 2014] p1992b-2015a Mr Peter Watson; Mr Mark McGowan; Ms Margaret Quirk; Mrs Michelle Roberts; Mr Paul Papalia; Mr Bill Johnston; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr David Templeman; Mr Joe Francis; Mr Sean L'Estrange; Mr Shane Love; Mr Ian Britza POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER Motion MR P.B. WATSON (Albany) [4.02 pm]: I move — That this house — (a) recognises the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder on Western Australians who have given service to the state and this country; (b) recognises and supports the need to raise awareness of the symptoms and effects of PTSD in the wider Western Australian community; and (c) formally declares the last Friday in June each year as “Invisible Wounds: PTSD Awareness Day” and encourages Western Australians to support events dedicated to marking this day. I would like to thank the Partners of Veterans Association group who have come here today: Sandra Cross, president; Kerryn McDonnell, secretary; Gloria Fox; Jude Firth; Lyn Wesson; and Ros Whitney. These ladies wrote to every state and federal member of Parliament asking for a day to be put aside each year for “Invisible Wounds: PTSD Awareness Day”. Many members are already familiar with post-traumatic stress disorder syndrome; however, the establishment and official sanction through Parliament of a PTSD awareness day will help immensely. Partners and veterans wrote letters to members of Parliament asking for a bipartisan approach to establish the last Friday in June as “Invisible Wounds: PTSD Awareness Day”. The motion calls to recognise the effect of PTSD on Western Australians who have given service to this state and this country. -

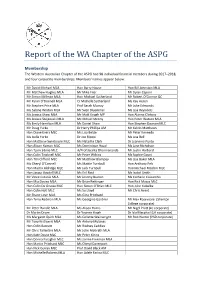

Report of the WA Chapter of the ASPG

Report of the WA Chapter of the ASPG Membership The Western Australian Chapter of the ASPG had 98 individual financial members during 2017–2018, and four corporate memberships. Members’ names appear below: Mr David Michael MLA Hon Barry House Hon Bill Johnston MLA Mr Matthew Hughes MLA Mr Mike Filer Mr Dylan Caporn Mr Simon Millman MLA Hon Michael Sutherland Mr Robert O’Connor QC Mr Kyran O’Donnell MLA Cr Michelle Sutherland Ms Kay Heron Mr Stephen Price MLA Prof Sarah Murray Mr Luke Edmonds Ms Sabine Winton MLA Mr Sven Bluemmel Ms Lisa Reynders Ms Jessica Shaw MLA Mr Matt Keogh MP Hon Alanna Clohesy Ms Jessica Stojkovski MLA Mc Mihael McCoy Hon Peter Watson MLA Ms Emily Hamilton MLA Mr Daniel Shaw Hon Stephen Dawson MLC Mr Doug Yorke Dr Harry Phillips AM Mr Kelvin Matthews Hon Diane Evers MLC Ms Lisa Belde Mr Peter Kennedy Ms Izella Yorke Dr Joe Ripepi Ms Lisa Bell Hon Matthew Swinbourn MLC Ms Natasha Clark Dr Jeannine Purdy Hon Alison Xamon MLC Ms Dominique Hoad Ms Jane Nicholson Hon Tjorn Sibma MLC A/Prof Jacinta Dharmananda Mr Justin Harbord Hon Colin Tincknell MLC Mr Peter Wilkins Ms Sophie Gaunt Hon Tim Clifford MLC Mr Matthew Blampey Ms Lisa Baker MLA Ms Cheryl O’Connell Ms Mattie Turnbull Hon Anthony Fels Hon Martin Aldridge MLC Mr Jack Turnbull Hon Michael Mischin MLC Hon Jacqui Boydell MLC Ms Eril Reid Ms Isabel Smith Mr Vince Catania MLA Mr Jeremy Buxton Ms Catharin Cassarchis Hon Mia Davies MLA Mr Brian Rettinger Hon Rick Mazza MLC Hon Colin De Grussa MLC Hon Simon O’Brien MLC Hon John Kobelke Hon Colin Holt MLC Ms Su Lloyd -

Your Daughter??

Your daughter?? Pimps would be legal under Mr Porter’s Prostitution Bill. They could approach teens in your family! Photo courtesy D Sharon Pruitt The Prostitution Bill was tabled in the WA Legislative Assembly on 3 November 2011 and could come to a vote soon. If the bill passes, pimps or madams could approach 18 year old girls like this one, offering them big dollars to work in a legal brothel. There would be nothing you could do to prevent it. The teens would discover – too late – that prostitution is a terrible trap few manage to escape. Your local state MP needs to know how you feel about this bill! Send him or her a brief email or phone their office ASAP (details overleaf). Be polite, and be sure to include your name and home address. Send a copy to Premier Colin Barnett and Attorney-General Christian Porter. Ask them to reject the Prostitution Bill. Briefly say why, including some points below (choose a couple) in your own words: In every Australian state that has legalised or decriminalised the sex trade there has been an upsurge in prostitution – in both legal and illegal brothels – and sex trafficking and slavery. It is “out of control” (The Age, 7/3/11; SMH, 13/10/11). Four Corners (ABC1, 10/10/11) showed scenes of pimping, sex trafficking and sex slavery in legal brothels in Victoria and NSW: http://www.abc.net.au/4corners/stories/2011/10/06/3333668.htm Research shows that most prostitutes suffer mental ill-health, including post traumatic stress disorders, because of their experiences. -

18-Phillips WA Election

The 2008 Western Australian State Election: The Snap Poll Blunder * Harry Phillips ** Following the 6 September 2008 election in Western Australian, and a week of tense negotiations, the presence of ‘wall to wall’ Labor Governments across Australia was broken. In a significant moment in the evolution of the Western Australian Parliament an ‘alliance’ headed by Colin Barnett, the Liberal Party leader, formed government for the 38 th Parliament. Remarkably, Barnett had been reinstated to the party leadership a few days before the campaign ‘caretaker phase’. 1 The Liberal Party leadership had successively been in the hands of Matt Birney (to March 2006), Paul Omodie (to January 2008) and Troy Buswell, 2 each of whom had returned very poor poll readings. With the Liberal’s experiencing long term serious leadership problems, both the polls and pundits had been predicting a Labor return to office with Alan Carpenter to remain as Premier. However, Carpenter’s decision to call a snap election, the first since the passage of the ‘one vote one value’ legislation for the Legislative Assembly, nearly six months ahead of schedule broke a century of tradition in the State whereby governments served a full term. There were vital pieces of legislation lying on the table 3 and the scheduled regional sitting of the Legislative Assembly in the marginal seat of Bunbury in early * Thanks are due to Antony Green for the electoral aggregates, preference and swing calculations included in this article and to Judy Ballantyne, State Parliamentary Library Director in Western Australia for permission to use data included in the electoral analysis prepared by Antony Green for the Parliamentary Library 2009.