Mirror Mirror" from the Opera, Dog Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

Verdi Falstaff

Table of Opera 101: Getting Ready for the Opera 4 A Brief History of Western Opera 6 Philadelphia’s Academy of Music 8 Broad Street: Avenue of the Arts Con9tOperae Etiquette 101 nts 10 Why I Like Opera by Taylor Baggs Relating Opera to History: The Culture Connection 11 Giuseppe Verdi: Hero of Italy 12 Verdi Timeline 13 Make Your Own Timeline 14 Game: Falstaff Crossword Puzzle 16 Bard of Stratford – William Shakespeare 18 All the World’s a Stage: The Globe Theatre Falstaff: Libretto and Production Information 20 Falstaff Synopsis 22 Meet the Artists 23 Introducing Soprano Christine Goerke 24 Falstaff LIBRETTO Behind the Scenes: Careers in the Arts 65 Game: Connect the Opera Terms 66 So You Want to Sing Like an Opera Singer! 68 The Highs and Lows of the Operatic Voice 70 Life in the Opera Chorus: Julie-Ann Whitely 71 The Subtle Art of Costume Design Lessons 72 Conflicts and Loves in Falstaff 73 Review of Philadelphia’s First Falstaff 74 2006-2007 Season Subscriptions Glossary 75 State Standards 79 State Standards Met 80 A Brief History of 4 Western Opera Theatrical performances that use music, song Music was changing, too. and dance to tell a story can be found in many Composers abandoned the ornate cultures. Opera is just one example of music drama. Baroque style of music and began Claudio Monteverdi In its 400-year history opera has been shaped by the to write less complicated music 1567-1643 times in which it was created and tells us much that expressed the character’s thoughts and feelings about those who participated in the art form as writers, more believably. -

Soldier Songs Production Photos from the Atlanta Opera, San Diego Opera, and Beth Morrison Projects Tough Questions and Tough Stories David T

Soldier Songs production photos from The Atlanta Opera, San Diego Opera, and Beth Morrison Projects Tough Questions and Tough Stories David T. Little (1978– ) has so far composed 8 operas/oratorios, 15 instrumental pieces for orchestra and large ensemble, 21 works for small ensemble, 7 choral and vocal works, and 11 solo compositions. Peruse titles on his website—Dog Days, JFK, A Nest of Shadows, Haunted Topography, Conspiracy Theory—and it is clear that he tackles thorny subject matter, asks tough questions, and tells tough stories. The New Yorker describes Little as “one of the most Music and Libretto by David Music T.andDavid Libretto by Little imaginative young composers” on the scene Select works by David T. Little: and The New York Times stated that he has “a knack Soldier Songs A 60-minute multimedia for overturning musical work for baritone and amplified septet that Soldier Songs conventions.” explores the perceptions versus the realities of a soldier, the exploration of loss For Soldier Songs, Little and exploitation of innocence, and the gathered tough stories, difficulty of expressing the truth of war. added elements of theater, opera, rock-infused-concert Am I Born An oratorio for soprano, music, and animation, and children's chorus, and orchestra that then delivered an evening- explores lost histories, altered places, and length event meant to be a the spiritual bleed at the intersection of vehicle for reflection, modernity and antiquity. engagement, and emotional connection. Vinkensport, or The Finch Opera If the purpose of the arts is A one-act operatic comedy about the not to produce products, Flemish folk-sport of finch-sitting. -

First Glimpse 2018: Songs from the Great Room

presents First Glimpse 2018: Songs from the Great Room World Premiere Songs rom e 17-19 omosers e oie series Composers & the Voice Artistic Director - Steven Osgood Musical Direction by Mila Henry & Kelly Horsted 2017-19 Composers & the Voice Composer and Librettist Fellows Laura Barati Pamela Stein Lynde Sokunthary Svay Matthew Browne Scott Ordway Amber Vistein Kimberly Davies Frances Pollock Alex Weiser 2017-18 Composers & the Voice Resident Singers Tookah Sapper, soprano Jennifer Goode Cooper, soprano Blythe Gaissert, mezzo-soprano* Blake Friedman, tenor Mario Diaz Moresco, baritone Adrian Rosas, bass-baritone *Songs written for mezzo-soprano will be performed tonight by Kate Maroney Resident Stage Manager - W. Wilson Jones May 19 & 20, 2018 - 7:30 PM SOUTH OXFORD SPACE, BROOKLYN FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR I always have mixed emotions when a cycle of Composers and the Voice arrives at the First Glimpse concerts. It is thrilling to FINALLY throw open the doors of this room and share some of the wonderful pieces that have been written since last Fall. But it also means that my time working so regularly and directly with a family of artists is drawing to a close. It takes a huge team of people to make a program like Composers and the Voice work, but I would like to thank two who have stepped into new and significantly larger roles this year. Mila Henry, C&V Head of Music, has overseen the musical organization of the entire season, while also preparing several pieces for each of our workshop sessions. Matt Gray, as C&V Head of Drama, has brought his insight into character and operatic narrative into every element of the program. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

The 2009 Lotte Lenya Competition First Round

The 2009 Lotte Lenya Competition Lauren Worsham’s recent credits include Sophie in Master Class (Pa- permill Playhouse), Clara in The Light in the Piazza (Chamber Version - Kilbourn Hall, Eastman School of Music Weston Playhouse), Cunegonde in Candide (New York City Opera), Jerry Springer: The Opera (Carnegie Hall), Olive in The 25th Annual Putnam Saturday, 18 April 2009 County Spelling Bee (First National Tour). New York workshops/readings: Mermaid in a Jar, Le Fou at New Georges, The Chemist's Wife at Tisch, Mir- ror, Mirror at Playwright's Horizons, and Now I Ask You at Provincetown First Round Playhouse. Graduate of Yale University, 2005. Thanks for all the love and support from Bryan and Management 101. Most importantly, I owe it all to my amazing family. Proud member AEA! www.laurenworsham.com The Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc. administers, promotes, and perpetuates the legacies of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya. It encourages broad dissemination and appreciation of Weill’s music through support of performances, productions, recordings, and scholarship; it fosters understanding of Weill’s and Lenya’s lives and work within diverse cultural contexts; and, building upon the legacies of both, it nurtures talent, particularly in the creation, performance, and study of musical theater in its various manifestations and media. Established in 1998 by the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, the Lotte Lenya Competition provides a unique opportunity for talented young singer/actors to show their versatility in musical theater repertoire ranging from opera/operetta to contemporary Broadway, with Competition Administration, for the Kurt Weill Foundation: a focus on the varied works of Kurt Weill. -

CHAN 3000 FRONT.Qxd

CHAN 3000 FRONT.qxd 22/8/07 1:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 3000(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH David Parry PETE MOOES FOUNDATION Puccini TOSCA CHAN 3000(2) BOOK.qxd 22/8/07 1:14 pm Page 2 Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Tosca AKG An opera in three acts Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica after the play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou English version by Edmund Tracey Floria Tosca, celebrated opera singer ..............................................................Jane Eaglen soprano Mario Cavaradossi, painter ..........................................................................Dennis O’Neill tenor Baron Scarpia, Chief of Police................................................................Gregory Yurisich baritone Cesare Angelotti, resistance fighter ........................................................................Peter Rose bass Sacristan ....................................................................................................Andrew Shore baritone Spoletta, police agent ........................................................................................John Daszak tenor Sciarrone, Baron Scarpia’s orderly ..............................................Christopher Booth-Jones baritone Jailor ........................................................................................................Ashley Holland baritone A Shepherd Boy ............................................................................................Charbel Michael alto Geoffrey Mitchell Choir The Peter Kay Children’s Choir Giacomo Puccini, c. 1900 -

Marvin Hamlisch

tHE iRA AND lEONORE gERSHWIN fUND IN THE lIBRARY OF cONGRESS AN EVENING WITH THE MUSIC OF MARVIN HAMLISCH Monday, October 19, 2015 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building The Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress was established in 1992 by a bequest from Mrs. Gershwin to perpetuate the name and works of her husband, Ira, and his brother, George, and to provide support for worthy related music and literary projects. "LIKE" us at facebook.com/libraryofcongressperformingarts loc.gov/concerts Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Monday, October 19, 2015 — 8 pm tHE iRA AND lEONORE gERSHWIN fUND IN THE lIBRARY OF cONGRESS AN EVENING WITH THE mUSIC OF MARVIN hAMLISCH WHITNEY BASHOR, VOCALIST | CAPATHIA JENKINS, VOCALIST LINDSAY MENDEZ, VOCALIST | BRYCE PINKHAM, VOCALIST -

Media Release

Media Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: August 13, 2015 Contact: Edward Wilensky (619) 232-7636 [email protected] Soprano Patricia Racette Returns to San Diego Opera “Diva on Detour” Program Features Famed Soprano Singing Cabaret and Jazz Standards Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 7 PM at the Balboa Theatre San Diego, CA – San Diego Opera is delighted to welcome back soprano Patricia Racette for her wildly-acclaimed “Diva on Detour” program which features the renowned singer performing cabaret and jazz standards by Stephen Sondheim, Cole Porter, George Gershwin, and Edith Piaf, among others, on Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 7 PM at the Balboa Theatre. Racette is well known to San Diego Opera audiences, making her Company debut in 1995 as Mimì in La bohème, and returning in 2001 as Love Simpson in Cold Sassy Tree (a role she created for the world premiere at Houston Grand Opera), in 2004 for the title role of Katya Kabanova, and in 2009 as Cio-Cio San in Madama Buttefly. She continues to appear regularly in the most acclaimed opera houses of the world, including the Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Houston Grand Opera, Washington National Opera, Los Angeles Opera, and Santa Fe Opera. Known as a great interpreter of Janáček and Puccini, she has gained particular notoriety for her portrayals of the title roles of Madama Butterfly, Tosca, Jenůfa, Katya Kabanova, and all three leading soprano roles in Il Trittico. Her varied repertory also encompasses the leading roles of Mimì and Musetta in La bohème, Nedda in Pagliacci, Elisabetta in Don Carlos, Leonora in Il trovatore, Alice in Falstaff, Marguerite in Faust, Mathilde in Guillaume Tell, Madame Lidoine in Dialogues of the Carmélites, Margherita in Boito’s Mefistofele, Ellen Orford in Peter Grimes, The Governess in The Turn of the Screw, and Tatyana in Eugene Onegin as well as the title roles of La traviata, Susannah, Luisa Miller, and Iphigénie en Tauride. -

Topical Weill: News and Events

Volume 27 Number 1 topical Weill Spring 2009 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news & news events Summertime Treats Londoners will have the rare opportunity to see and hear three Weill stage works within a two-week period in June. The festivities start off at the Barbican on 13 June, when Die Dreigroschenoper will be per- formed in concert by Klangforum Wien with HK Gruber conducting. The starry cast includes Ian Bostridge (Macheath), Dorothea Röschmann (Polly), and Angelika Kirchschlager (Jenny). On 14 June, the Lost Musicals Trust begins a six-performance run of Johnny Johnson at Sadler’s Wells; Ian Marshall Fisher directs, Chris Walker conducts, with Max Gold as Johnny. And the Southbank Centre pre- sents Lost in the Stars on 23 and 24 June with the BBC Concert Orchestra. Charles Hazlewood conducts and Jude Kelly directs. It won’t be necessary to travel to London for Klangforum Wien’s Dreigroschenoper: other European performances are scheduled in Hamburg (Laeiszhalle, 11 June), Paris (Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, 14 June), and back in the Klangforum’s hometown, Vienna (Konzerthaus, 16 June). Another performing group traveling to for- eign parts is the Berliner Ensemble, which brings its Robert Wilson production of Die Dreigroschenoper to the Bergen Festival in Norway (30 May and 1 June). And New Yorkers will have their own rare opportunity when the York Theater’s “Musicals in Mufti” presents Knickerbocker Holiday (26–28 June). Notable summer performances of Die sieben Todsünden will take place at Cincinnati May Festival, with James Conlon, conductor, and Patti LuPone, Anna I (22 May); at the Arts Festival of Northern Norway, Harstad, with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra led by HK Gruber and Ute Gfrerer as Anna I (20 June); and in Metz, with the Orchestre National de Lorraine, Jacques Mercier, conductor, and Helen Schneider, Anna I (26 June). -

DTL BIO-CV-Fall 2013

DAVID T. LITTLE Composer / Performer 93 Clifton Terrace, Apartment No. 5 - Weehawken, NJ 07086 - (908)-642-1736 [email protected] www.DavidTLittle.com EDUCATION Princeton University (2006-2011) Doctor of Philosophy, Composition, Spring 2011 Primary Teachers: Paul Lansky, Steven Mackey, Dmitri Tymoczko Thesis Paper: The Critical Composer: Political Music During And After “The Revolution” Thesis Composition: Soldier Songs Thesis Advisor: Paul Lansky Naumberg Fellow (2006-2008) The Princeton dissertation consists of two components, a written thesis, and a substantial composition. My paper is historical and analytic in nature. It explores the influence of leftist ideology and anti- communist political landscapes on activist-minded classical music throughout the 20th century. It further cites the emergence a new kind of composer/social-critic in the wake of the ended Cold War in the absence of said ideology. My composition was my first opera, Soldier Songs. Princeton University (2004-2006) Master of Fine Arts, Composition Primary Teachers: Steven Mackey, Paul Lansky, Dmitri Tymoczko, Barbara White Naumberg Fellow (2004-2006) University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (2001-2002) Master of Music, Composition Recipient of the Christine Rinaldo Memorial Scholarship Primary Teachers: William Bolcom, Michael Daugherty Thesis Composition: Screamer! – a three-ring blur for orchestra Susquehanna University (1997-2001) Bachelor of Music, Percussion Performance Music and Academic Scholarships magna cum laude, University Honors Primary Teachers: David Mattingly, -

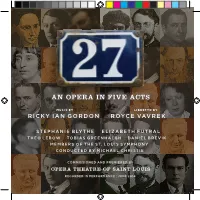

An Opera in Five Acts

AN OPERA IN FIVE ACTS MUSIC BY LIBRETTO BY RICKY IAN GORDON ROYCE VAVREK STEPHANIE BLYTHE ELIZABETH FUTRAL THEO LEBOW TOBIAS GREENHALGH DANIEL BREVIK MEMBERS OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY CONDUCTED BY MICHAEL CHRISTIE COMMISSIONED AND PREMIERED BY OPERA THEATRE OF SAINT LOUIS RECORDED IN PERFORMANCE : JUNE 2014 1 CD 1 1) PROLOGUE | ALICE KNITS THE WORLD [5:35] ACT ONE 2) SCENE 1 — 27 RUE DE FLEURUS [10:12] ALICE B. TOKLAS 3) SCENE 2 — GERTRUDE SITS FOR PABLO [5:25] AND GERTRUDE 4) SCENE 3 — BACK AT THE SALON [15:58] STEIN, 1922. ACT TWO | ZEPPELINS PHOTO BY MAN RAY. 5) SCENE 1 — CHATTER [5:21] 6) SCENE 2 — DOUGHBOY [4:13] SAN FRANCISCO ACT THREE | GÉNÉRATION PERDUE MUSEUM OF 7) INTRODUCTION; “LOST BOYS” [5:26] MODERN ART. 8) “COME MEET MAN RAY” [5:48] 9) “HOW WOULD YOU CHOOSE?” [4:59] 10) “HE’S GONE, LOVEY” [2:30] CD 2 ACT FOUR | GERTRUDE STEIN IS SAFE, SAFE 1) INTRODUCTION; “TWICE DENYING A WAR” [7:36] 2) “JURY OF MY CANVAS” [6:07] ACT FIVE | ALICE ALONE 3) INTRODUCTION; “THERE ONCE LIVED TWO WOMEN” [8:40] 4) “I’VE BEEN CALLED MANY THINGS" [8:21] 2 If a magpie in the sky on the sky can not cry if the pigeon on the grass alas can alas and to pass the pigeon on the grass alas and the magpie in the sky on the sky and to try and to try alas on the grass the pigeon on the grass and alas. They might be very well very well very ALICE B.