Mark and Janeth Sponenburgh Gallery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dale Chihuly Exhibition at Hallie Ford Artist’S Cylinders, Macchia, and Venetians from the George R

POPULATION 400,408 June 2021 VOL. 3, NO. 6 Dale Chihuly Exhibition AT Hallie Ford Artist’s Cylinders, Macchia, and Venetians from the George R. Stroemple Collection RECREATIONAL BOATING THIS SEASON JOY OF LIVING ASSISTANCE DOGS PAGE 10 PAGE 16 PAGE 13 Page 2 Salem Metro Area • Population 400,408 June 2021 Cover Photo Credits CLOCKWISE FROM UPPER LEFT Fresh, Local and Handmade Products Dale Chihuly (American, born 1941) at Salem Community Markets “Lavender Piccolo Venetian with Cerulean Lilies,” 1993, blown glass, 8 x 5 x 5 in., George R. Stroemple Collection, an S & S Collaboration, DC.152. “Light Violet Macchia Set with Black Lip Wrap,” 1983, blown glass, 13 x 13 x 8 in., George R. Stroemple Collection, DC.142. Photo: Jeff Freeman. “Ruby Red Putti Venetian with Gilt Ram and Twin-Headed Dragon,” 1994, blown glass, 20 x 12 x 12 in., George R. Stroemple Collection, an S & S Collaboration, DC.402. Photo: Claire Garoutte. “Fountain Green Putti Venetian with Gilt Leaves and Centaur,” 1994, blown glass, 18 x 17 x 17 in., George R. Stroemple Collection, an S & S Collaboration, DC.397. Photo: Claire Garoutte. “Fire Coral Macchia with Corsair Lip Wrap,” 1982, blown glass, 10 x 18 x 10 in., George R. Stroemple Collection, an S & S Collaboration, DC.115. Photo: Terry Rishel. “Silver over Starlight Blue Piccolo Venetian with Clear Prunts,” 1994, blown glass, 10 x 6 x 6 in., George R. Stroemple Collection, an S & S Collaboration, DC.210. Photo: Claire Garoutte. Photos Courtesy of The George R. Stroemple Collection. POPULATION 400,408 SBJ.NEWS PUBLISHER ART DIRECTOR Bruce Taylor P.K. -

Digital Commons @

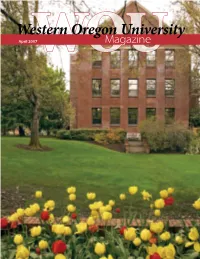

sALUMnotesALUMnotesALUMnotesALUMnotesALUMno Western Oregon University April 2007WOUMagazine 1 Alum n o tes Western Oregon University You watch your financesclosely . They do their best. The average education loan debt of many college students when they graduate exceeds the national average credit card debt of $9,000. Yesterday’s Western Oregon University student could work a summer job and earn enough money to pay their next year’s tuition and expenses. Over half of today’s WOU students work in the summer and during the school year to help pay for tuition and expenses. And still they graduate with an average education loan debt of nearly $20,000. Your contribution in support of student scholarships absolutely makes a difference! • Outright gifts • Gifts of appreciated assets such as property and securities • Charitable gift annuities Contact James Birken Director of Gift Planning Western Oregon University University Advancement The Cottage Monmouth, Oregon 97361 503-838-8145 [email protected] Western Oregon University Magazine © April 2007 • Volume 8, No. 2 What’s Inside PRESIDENT John P. Minahan Washington EXECUTIVE EDITOR Leta Edwards Vice President for University Advancement Envisioning the MANAGING EDITOR ‘06 Maria Austin future Coordinator of Alumni Programs 4 Oregon President discusses his three-year Idaho CONTRIBUTING WRITERS vision for WOU Maria Austin Russ Blunck Lori Jordan Brown Craig Coleman Leta Edwards Being prepared Lisa Pulliam WOU-based Homeland Security Nevada Alaska PHOTOGRAPHERS 6 grant assists Native Americans Lori -

PAT BOAS Education 2000 MFA Painting, Portland State University

PAT BOAS Education 2000 MFA Painting, Portland State University 1998 BFA Printmaking, Pacific Northwest College of Art 1976 Drawing & Painting, University of Akron Solo Exhibitions 2019 Memo, Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Portland, OR 2017 Cipher, Art in the Governor’s Office, Oregon Arts Commission, Salem, OR 2016 Logo(s), Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Portland, OR 2015 Encryption Machine, The Arlington Club, Portland, OR 2014 The Word Hand (Collaborative drawing performance and exhibition with visual artist Linda Hutchins and choreographer Linda Austin), Performance Works Northwest, Portland, OR The Word Hand: Research/Rehearse (Three-person collaborative drawing performance and exhibition), Weiden & Kennedy Gallery, Portland, OR 2009 Record Record, The Art Gym, Marylhurst University, Marylhurst, OR 2008 Idiomsyncretic, Emily Davis Gallery, University of Akron, Akron, OH 2007 Idiom, Fairbanks Gallery, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 2006 You haven no companion but Night, Nine Gallery, Portland, OR 2005 Mutatis Mutandis, Northview Gallery, Portland, OR Against Nature, Window Project, PDX Contemporary Art, Portland, OR 2001 Reading & Writing #5, Metropolitan Center for Public Art, Portland, OR Word Work, IMAG, Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland OR 2000 Textuaries, Autzen Gallery, Portland State University, Portland, OR 1997 Breath, Kathrin Cawein Gallery, Pacific University, Forest Grove, OR Selected Group Exhibitions 2019 Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts at 25, Boise Art Museum, Boise, ID 2018 Assemblage & Collage, Elizabeth Leach -

CASA Annual Report 2020

Fall 08 The Center for Ancient Studies and Archaeology Willamette University The Stones of Stenness at the Ness of Brodgar Report 2019-2020 1 Table of Contents Notes from Director Ortwin Knorr ............................................................................................................... page 3 CASA’S MISSION ........................................................................................................................................... Page 4 Student Programs ........................................................................................................................................ Page 4 Willamette University Archaeological Field School .............................................................................. Page 5 Student Archaeological Field School Scholarships ............................................................................... Page 7 Community Archaeology ...................................................................................................................... Page 8 Student Internship in Museology at the HFMA .................................................................................... Page 9 The Carl S. Knopf Award ....................................................................................................................... Page 10 Student Scholarship Recognition Day and Undergraduate Conference .............................................. Page 11 The Archaeology Program at Willamette University ........................................................................... -

Sherrie Wolf

SHERRIE WOLF Born: 1952, Portland, OR EDUCATION Chelsea College of Art, London, England; M.A. Printmaking 1975 Museum Art School, Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, OR; B.F.A. Painting 1974 ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS “Found,” Russo Lee Gallery, Portland, OR 2019 “Juxtapositions,” Russo Lee Gallery, Portland, OR 2018 “Postcards from Paris,” Russo Lee Gallery, Portland, OR 2017 “The Flower Paintings: A Tribute to Manet’s Last Paintings,” Arden Gallery, Boston, MA 2017 “Stage,” The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 2016 “Sherrie Wolf: Object Lessons,” Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Willamette University, Salem, OR 2015 “Tulips: A History,” Woodside/Braseth Gallery, Seattle, WA 2015 “Museum,” The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 2014 “Baroque Sensibilities: Sherrie Wolf,” Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, CA 2014 “Stills,” The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 2013 “Looking Back,” The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 2012 “Sherrie Wolf: Historyonics,” Northern Arizona University Art Museum Gallery, Flagstaff, AZ 2012 “Sherrie Wolf: Vessels,” Arden Gallery, Boston, MA 2011 “Transmissions,” The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 2011 “Sherrie Wolf: Paintings,” Arden Gallery, Boston, MA 2011 “Faces,” The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 2010 “New Paintings,” Arden Gallery, Boston, MA 2010 Gordon Woodside / John Braseth Gallery, Seattle, WA 2008, 2010 “Counterpoint,” The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 2009 “Animal Life,” Jenkins Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2009 The Laura Russo Gallery, Portland, OR 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008 “Virtue, -

James Lavadour

! JAMES LAVADOUR BORN Pendleton, Oregon (1951) SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 All that I can see from here, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR 2017 Recent Findings, Cumberland Gallery, Nashville, TN 2016 Ledger of Days, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR 2015 James Lavadour: Land of Origin, MAC Gallery, Wenatchee Valley College, Wenatchee, WA 2014 Fingering Instabilities, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR 2012 The Interior, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR 2011 Paintings, Grover/Thurston Gallery, Seattle, WA 2010 Geographies of the Same Stone: for TT, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR 2009 Grover/Thurston Gallery, Seattle, WA 2008 The Properties of Paint, Hallie Ford Museum, Willamette University, Salem, OR; (traveled): Schneider Museum of Art, Southern Washington University, Ashland, OR; Tamastslikt Cultural Institute, Pendleton, OR Close to the Ground, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR 2006 Sun Spots, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR Rain, Cumberland Gallery, Nashville, TN Magic Valley, Gail Severn Gallery, Ketchum, ID 2005 Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, Indianapolis, IN Grover/Thurston Gallery, Seattle,WA Walk, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR (shown at 219 NW 12th) 2004 Cumberland Gallery, Nashville, TN 2003 Romantic Landscape, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR New Camp, Grover Thurston, Seattle, WA Gail Severn Gallery, Ketchum, ID 2002 Intersections II, PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland, OR Intersections, Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, WA 2001 Retrospective, Northwest Museum of Arts & Culture, Spokane, -

Roger Shimomura: While Donations Have Played an Important Role in the Development of Our of Law 21 Film Tuesday, Sept

A Contemporary Bestiary If You Like What We Visit Our Museum Store AID Are Doing, Become Visit our museum store for a wide 52 a Member variety of art books and related merchandise. Remember, art Membership revenue helps support mit No.1 books and art-related gift items Salem, OR collections, exhibitions, education Per US Postage P make wonderful gifts for birthdays, NONPROFIT ORG and outreach, so if you like what we graduations and other special are doing, become a Hallie Ford occasions, and as a family or dual- Museum of Art member. level member, you receive a 10 As a member, you will enjoy the percent discount. many benefits we have to offer, Right: including unlimited free admission; Facility Rentals Robert invitations to previews and special McCauley, Located in the heart of downtown Edge of members’ receptions; discounts on Salem, the Hallie Ford Museum Town II art books and related merchandise; (detail), of Art is an elegant and unique annual subscriptions to Brush- 2012 setting for your next special strokes and Willamette University’s event, from cocktail receptions Below: magazine, The Scene; invitations to Deborah and dinners to business special lectures, films, concerts and Butterfield, meetings and presentations. For Red Forest tours; and more. further information on capacity, (detail), And, if you are already a member, availability, rental rates and 2013 consider giving a gift membership restrictions, call Carolyn Harcourt A Contemporary Bestiary features work by artists from Oregon, Washington, Idaho, to a friend or relative. Memberships at 503-370-6856 or visit Montana, and British Columbia who incorporate animal imagery in their artwork as make wonderful gifts for birthdays, willamette.edu/go/rent_hfma. -

2017 Oregon Governor's Arts Awards Program

GOVERNOR’S ARTS AWARDS FRIDAY, OCTOBER , MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR KATE BROWN Governor Dear Arts Supporters, I am honored to welcome you to the 2017 Governor’s Arts Awards. The Oregon Arts Commission has made sure art is a part of our daily lives for the past 50 years. In honor of this historic anniversary, I am proud to reinstate the Governor’s Arts Awards and to once again honor artists and organizations that make outstanding contributions to the arts in Oregon. Art is a fundamental ingredient of any thriving and vibrant community. Art sparks connections between people, movements and new ideas. Here in Oregon, the arts enrich our quality of life and local economies, helping form our great state’s unique identity. Not only that, art education is key in fostering a spirit of creativity and innovation in our youth. I want to thank each of you for being a part of this community, making Oregon more beautiful, more alive every day. Each of today’s Arts Awards recipients has touched the lives of thousands of Oregonians in meaningful ways. They were selected through a highly competitive process from a field of 110 worthy nominees and are extremely deserving of this honor. I thank them for making Oregon a better and more beautiful place and ask you to join with me in celebrating their achievements. Sincerely, Governor Kate Brown PROGRAM WELCOME Christopher Acebo • Chair, Oregon Arts Commission PERFORMANCE BRAVO Youth Orchestras & Darrell Grant AWARDS Presented by Governor Kate Brown COMMUNITY AWARD Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Arvie Smith PHILANTHROPY AWARD The James F. -

Northwest Impressionism, 1910-1935

Hidden in Plain Sight: Northwest Impressionism, 1910-1935 John E. Impert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Susan Casteras, Chair René Bravmann Douglas Collins Program authorized to Offer Degree: Art History University of Washington Abstract Hidden in Plain Sight: Northwest Impressionism, 1910-1935 John E. Impert Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Susan Casteras Art History Northwest Impressionist artists are among the forgotten figures in American art history. Responsible for bringing Modernism to Washington and Oregon, they dominated the art communities in Seattle and Portland from about 1910 to 1928, remaining influential until the mid 1930’s. After describing the artists briefly, this dissertation summarizes and evaluates the slim historiography of Northwest Impressionism. Impressionism and Tonalism are contrasted in order to situate these artists within the broad currents of American art history. Six important artists who have not been studied in the past are each accorded a chapter that summarizes their educations, careers, and artistic developments. In Seattle, Paul Gustin, the early leader of the Seattle art community, was most closely associated with images of Mount Rainier. Edgar Forkner, a well established Indiana artist, moved to Seattle and painted numerous canvases of old boats at rest and still lifes of flowers. Dorothy Dolph Jensen, a latecomer, emphasized shoreline and harbor scenes in her work. In Portland, Charles McKim traded complete anonymity in Portland, Maine for the leadership of the Oregon art community, creating a variety of landscapes and seascapes. Clyde Keller produced an enormous output of landscapes over a long career that extended to California as well as Oregon. -

Christy Wyckoff 2402 SE Main Portland OR 97214 USA [email protected]

Christy Wyckoff 2402 SE Main Portland OR 97214 USA [email protected] www.christywyckoff.com PUBLIC AND CORPORATE COLLECTIONS Anchorage Museum Museu Nacional del Grabado, Buenos Aires, Argentina Art Coll Trust, Bellevue New York Public Library, NYC Arthur Anderson Company, Portland Northwest Acceptance, Portland Boise Art Museum, Boise, ID Northwest Power Council, Portland Bonneville Power Administration, Portland Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland Beaverton School District, Beaverton, Oregon Ore St. Capitol Building, Salem Central Oregon Community College Library, Bend Ore St. Employment Office, Salem China National Academy of Art, Beijing, PRC Ore St. Revenue Building, Salem City of Denver, Red Rocks Amphitheater Ore St. Corrections Division City of Seattle Portland Art Museum, Vivian & Gordon Gilkey Collection Eugene Water and Electric Board, Eugene, Oregon Portland School District, Portland Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington Portland State University, Portland First National Bank, Atlanta Qingdao Art Gallery, Qingdao, People’s Republic of China Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Willamette U, Salem, Oregon Salishan Lodge, Gleneden Beach, Oregon Hawai’i State Portable Collection, Honolulu Seattle Art Museum, Seattle Heathman Hotel, Portland Seattle Public Utilities Portable Works Collection Hoffman Construction, Portland Security Pacific Bank, Portland IBM, Houston Southern Oregon State University Intel Corporation, Portland Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, Washington Jordan Schnitzer Art Museum at University of Oregon, Tonken, Torp and Galen, Portland Haseltine Collection, Eugene United First Federal Savings, Boise Kaiser Permanente, Portland United States Information Service Kerns Art Center, Eugene University of Applied Sciences, Amman, Jordan Mentor Graphics, Portland Veteran's Affairs Building, Salem Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC Visual Arts Chronicle, Portland Minnesota Museum of Art, St. -

Curator and Critic Tours Connective Conversations

CURATOR AND CRITIC TOURS CONNECTIVE CONVERSATIONS: INSIDE OREGON ART 2011–2014 THE FORD FAMILY FOUNDATION AND UNIVERSITY OF OREGON 2 3 The Ford Family Foundation’s Visual Arts program honors the interests in the visual arts by Mrs. Hallie Ford, a co-founder of The Foundation. The principal goals are to help enhance the quality of artistic endeavor and body of work by Oregon’s most promising visual artists and to improve Oregon’s visual arts ecology by making strategic investments in Oregon visual arts institutions. The program was launched in 2010, and in 2014 it was extended through TABLE OF CONTENTS 2019. The Foundation supports a range of program components, among them Connective Conversations as part of the Curator and Critic Tours and Lectures Series during which it partners with regionally-based institutions to invite professionals from outside the Northwest to conduct one-on-one studio visits and to join in community conversations. The Ford Family Foundation has collaborated with the University of Oregon School of Architecture and Allied Arts to conduct the Connec- o6 o7 o8 tive Conversations | Inside Oregon Art Series since its launch in 2011. THE FORD FAMILY INTRODUCTION IN THE STUDIO Kate Wagle, Director, George Baker, Curator Critic The Curator and Critic Tours and Lectures Series is the seventh and final FOUNDATION element of The Ford Family Foundation’s Visual Arts Program’s investment in VISUAL ARTS PROGRAM UO School of Architecture Professor of Art History Oregon visual arts institutions. Anne C Kubisch, President, and Allied Arts in Portland University of California This publication is made possible by The Ford Family Foundation and the University of Oregon. -

For Immediate Release: August 22, 2017 Media Contact: Andrea Foust Membership and Public Relations Manager Hallie Ford Museum Of

For immediate release: August 22, 2017 Media contact: Andrea Foust Membership and Public Relations Manager Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University | 503-370-6867 Public contact: 503-370-6855 | [email protected] Exhibition website: http://willamette.edu/go/crows-shadow-25 Exhibition Celebrates the 25th Anniversary of Crow's Shadow Institute of the Arts Organized by the Hallie Ford Museum of Art in partnership with the Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts (CSIA), a new exhibition chronicles the history of Crow’s Shadow over the past 25 years as it has emerged as a nationally recognized printmaking studio located on the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation near Pendleton, Oregon. "Crow's Shadow Institute of the Arts at 25" opens September 16 in the Melvin Henderson-Rubio Gallery and continues through December 22. The exhibition features 75 prints drawn from the Crow’s Shadow Print Archive and focuses on themes of landscape, abstraction, portraiture, word and images, and media and process. Included in the exhibition are works by 50 Native and non-Native artists who have worked at CSIA, including Rick Bartow, Pat Boas, Joe Feddersen, Edgar Heap of Birds, James Lavadour, Truman Lowe, Lillian Pitt, Wendy Red Star, Storm Tharp, and Marie Watt, among others. The CSIA was founded by Oregon painter and printmaker James Lavadour (Walla Walla), who envisioned a traditional arts studio focused on printmaking. Art historian Prudence Roberts says of Lavadour, "He wanted to contribute to the Tribes’ new sense of direction and self-sufficiency, and also to give emerging artists opportunities and a sense of community that had eluded him as he taught himself his craft." Today, CSIA is perhaps the only professional printmaking studio located on a reservation community in the United States.