Abbreviations Used in Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iowans Harry Hopkins and Henry A. Wallace Helped Craft Social Security's Blueprint

Iowans Harry Hopkins and Henry A. Wallace Helped Craft Social Security's Blueprint FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM by David E. Balducchi staggering 25 percent of American workers were unemployed. Poverty rates for the el Aderly neared 50 percent. The spring of 1934 was a time of colossal hardship. In the months to come, however, Iowans Harry Lloyd Hopkins and Henry Agard Wallace would help invent the land mark Social Security Act, which would include un employment insurance. While Hopkins and Wallace are known as liberal lions of the New Deal in areas of work relief and agricultural policy, their influential roles on the cabinet-level Committee on Economic Security are little known. Harry Hopkins was born in Sioux City in 1890, where his father operated a harness shop. The family lived in Council Bluffs and a few other midwestern towns. When Hopkins was 11, they settled in Grin- nell; his mother hoped her children could attend col lege there. Hopkins graduated from Grinnell College in 1912 and then began to make a name for himself in child welfare, unemployment, work relief, and public health, particularly in New York City. Agree ing with New York Governor Franklin Delano Roos evelt's push for aggressive unemployment relief measures, Hopkins supported Roosevelt's presiden tial bid. In May 1933 he joined Roosevelt in Wash ington as the bulldog head of the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). His mastery of inter preting and carrying out Roosevelt's wishes later would make him the president's closest advisor. Iowa-born Harry Hopkins was a key m em ber on the cabinet- level Com m ittee on Economic Security. -

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

Henry Wallace, America's Forgotten Visionary

Henry Wallace, America's Forgotten Visionary http://truth-out.org/opinion/item/14297-henry-wallace-americas-forgotten-... Sunday, 03 February 2013 06:55 By Peter Dreier, Truthout | Historical Analysis One of the great "What if?" questions of the 20th century is how America would have been different if Henry Wallace rather than Harry Truman had succeeded Franklin Roosevelt in the White House. Filmmaker Oliver Stone has revived this debate in his current ten-part Showtime series, "The Untold History of the United States," and his new book (written with historian Peter Kuznick) of the same name. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, only FDR eclipsed Wallace - Roosevelt's secretary of agriculture (1933-1940) and then his vice president (1941-1944) - in popularity with the American people. Stone's documentary series and book portray Wallace as a true American hero, a "visionary" on both domestic and foreign policy. Today, however, Wallace is a mostly forgotten figure. If Stone's work helps restore Wallace's rightful place in our history and piques the curiosity of younger Americans to learn more about this fascinating person, it will have served an important purpose. Henry Agard Wallace. (Photo: Department of Commerce) Wallace almost became the nation's president. In 1940, he was FDR's running mate and served as his vice president for four years. But in 1944, against the advice of the Democratic Party's progressives and liberals - including his wife Eleanor - FDR reluctantly allowed the party's conservative, pro-business and segregationist wing to replace Wallace with Sen. Harry Truman as the vice presidential candidate, a move that Stone calls the "greatest blunder" of Roosevelt's career. -

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library & Museum

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library & Museum Collection: Grace Tully Archive Series: Grace Tully Papers Box 7; Folder = Logs of the President's Trips: Casablanca Conference, January 9-31, 1943 1943 9-31, January Conference, Papers Tully Casablanca Grace Trips: Series: President's the Archive; of Tully Logs Grace Folder= 7; Collection: Box THE CASABLANCA TRIP 9-31 r o,r.;:i.ginaJY OF LOG January, TO .00000. THE 1943 THE ret;i.iei! OF CONFERENCE , 9-31, 1943 PRESIDENT January , Conference, Papers Tully Casablanca Grace Trips: Series: President's the Archive; of Tully Logs Grace Folder= 7; Collection: Box ":' ':;~,' :-Origina,l Fo.REWORD In December 1942 the Commander-in-Chief, Franklin D. Roosevelt, decided, to rendezvous. with the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill, -. at a suitable place in North Africa. Thus would the President and the PrUne Minister be afforded an op- portunity to confer, and, with their military and naval staffs, inspect the United Nations r- forces which had landed successfully in North Africa -the previous November. Plans for transporting the President and his party by land and air were drawn up. Advance 1943 parties comprising Secret Service agents, as well as 9-31, military and naval advisors, left early in January 1943. In this manner arrangements were perfected January .along ·the route which the President waS to follow Conference, through North America and South America to the oonti~ Papers nent of Afric~. Tully Casablanca Grace Trips: Series: President's the Archive; of Tully Logs Grace Folder= 7; Collection: Box [ [ . THE PRESIDENT'S PA'lTY r l The Pre sid e n t Mr. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

Hard Patience by MELINDA CREECH

Copyright © 2016 Institute for Faith and Learning at Baylor University 67 Hard Patience BY MELINDA CREECH In one of his so-called “terrible sonnets” or “sonnets of desolation,” Gerard Manley Hopkins confronts how very hard it is to ask for patience and to see the world from God’s perspective. Yet patience draws us ever closer to God and to his “delicious kindness.” uring his Long Retreat of November-December 1881-1882, Gerard Manley Hopkins copied into his spiritual writings notebook this Deighth “Rule for the Discernment of Spirits” from the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola: “Let him who is in desolation strive to remain in patience, which is the virtue contrary to the troubles which harass him; and let him think that he will shortly be consoled, making diligent effort against the desolation.”1 Patience was to become a focus for Hopkins during the last eight years of his life, strained slowly out of the experiences of life and distilled from his attentive study of creation, other people, and spiritual writings. As Ignatius counseled, it was to be patience in the midst of desola- tion, and Hopkins knew a fair bit of desolation in his short forty-four years. Growing up in a well-to-do religiously pious Anglican family, Hopkins excelled at Highgate School, London, and attended Balliol College, Oxford, receiving highest honors in both his final exams, Greats and Moderns. He converted to Catholicism during his last year at Balliol and later he entered the Jesuit order. During these early years he struggled with conflicts he per- ceived between his identities as priest, professor, and poet. -

The Department of Justice and the Limits of the New Deal State, 1933-1945

THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE LIMITS OF THE NEW DEAL STATE, 1933-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Ponomarenko December 2010 © 2011 by Maria Ponomarenko. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/ms252by4094 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Kennedy, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard White, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mariano-Florentino Cuellar Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements My principal thanks go to my adviser, David M. -

Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter Volume 20, Number 4 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Kentucky Library - Serials Society Newsletter Fall 1997 Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter Volume 20, Number 4 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/longhunter_sokygsn Part of the Genealogy Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter Volume 20, Number 4" (1997). Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter. Paper 129. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/longhunter_sokygsn/129 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Longhunter, Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society Newsletter by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME XX - ISSUE 4 SOUTHERN KENTUCKY GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY P.o. Box 1782 Bowling Green, KY 42102 - 1782 1997 OFFICERS President Mark Lowe Springfield, TN ph. 800-556-4021 Vice President John E. Danielson, PO Box 1843 Bowling Green, KY 42102-1843 Recording Secretary Gail Miller, 425 Midcrest Dr. Bowling Green, KY 42101 ph. 502-781-1807 Corresponding Secretary Betty B. Lyne, 613 E. Ilth Ave. Bowling Green, KY 42101 ph. 502-843-9452 Treasurer Ramona Bobbitt. 2718 Smallhouse J<.d. Bowling Green, KY 42104 ph. 502-843-6918 Chaplain A. Ray Douglas, 439 Douglas Lane Bowling Green. KY 42101 ph. 502-842-7101 Longhunter Editors Sue and Dave Evans, 921 Meadowlark Dr. Bowling Green, KY 42103 ph. 502-842-2313 MEMBERS HlP Membership in the Southern Kentucky Genealogical Society is open to all persons, especially to those who are interested in research in Allen, Barren, Butler. -

Harry Hopkins: Social Work Legacy and Role in New Deal Era Policies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Houston Institutional Repository (UHIR) Harry Hopkins: Social Work Legacy and Role in New Deal Era Policies Marcos J. Martinez, M.S.W. Elisa Kawam, M.S.W. Abstract The early 20th century was rife with much social, political, and economic change both positive and negative. During this time, social work became a profession, cemented by great minds and visionaries who sought a better society. Harry Hopkins was one such visionary: he was a model leader in social service provision and was one of the New Deal architects. This essay considers the roots of Hopkin’s influence, his experiences operating large federal agencies, his work in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration during the Great Depression and into World War II, and the dedication and commitment he displayed throughout his career as a public servant. Keywords: social work, Harry Hopkins, New Deal, FDR Administration “Now or never, boys—social security, minimum wage, work programs. Now or never.” –Harry Hopkins (Sherwood, 1948 as cited in Goldberg & Collins, 2001, p.34) Introduction At the turn of the century and into the decades of the early 20th century that followed, the United States saw a time of great struggle and change. Known as the Progressive era, the years between 1875 and 1925 were marked by the obtainment of labor rights for workers and children, the Women’s Suffrage movement, U.S. involvement in World War I (1914-1918) and the subsequent economic boom, and establishment of the social welfare system (Goldberg & Collins, 2001; Kawam, 2012; Segal, 2013). -

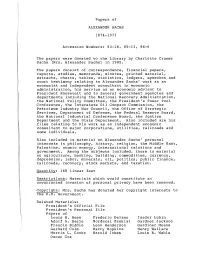

Papers of ALEXANDER SACHS 1874-1973 Accession Numbers

Papers of ALEXANDER SACHS 1874-1973 Accession Numbers: 83-16, 85-13, 86-6 The papers were donated to the Library by Charlotte Cramer Sachs (Mrs. Alexander Sachs) in 1985. The papers consist of correspondence, financial papers, reports, studies, memoranda, minutes, printed material, extracts, charts, tables, statistics, ledgers, speeches and court testimony relating to Alexander Sachs' work as an economist and independent consultant in economic administration, his service as an economic advisor to President Roosevelt and to several government agencies and departments including the National Recovery Administration, the National Policy Committee, the President's Power Pool Conference, the Interstate Oil Compact Commission, the Petroleum Industry War Council, the Office of Strategic Services, Department of Defense, the Federal Reserve Board, the National Industrial Conference Board, the Justice Department and the State Department. Also included are his files relating to his work as an independent economic consultant to major corporations, utilities, railroads and some individuals. Also included is material on Alexander Sachs' personal interests in philosophy, history, religion, the Middle East, Palestine, atomic energy, international relations and government. Among the subjects included, there is material on agriculture, banking, building, commodities, currency, depression, labor, minerals, oil, politics, public finance, railroads, recovery, stock markets, and taxation. Quantity: 168 linear feet Restrictions: Materials which would constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy have been removed. Copyright: Mrs. Sachs has donated her copyright interests to the u.s. Government. Related Materials: President's Official File President's Personal file Papers of Louis H. Bean Frederic Delano Isador Lubin Adolf A. Berle Mordecai Ezekial Gardner Jackson Francis Biddle Leon Henderson Gardiner Means Gerhard Colm Harry Hopkins Henry Wallace Morris L. -

Mid-Atlantic Conference on British Studies 2015 Annual Meeting The

Mid-Atlantic Conference on British Studies 2015 Annual Meeting The Johns Hopkins University March 27-28, 2015 Friday March 27 All events will take place at Charles Commons unless otherwise noted. 10:00am–12:00pm Registration and Coffee Registration Area SESSION ONE: 12:00-1:30pm i. Historicizing the English Garden: Space, Nature, and National Identity in Modern Britain Salon A i. Robyn Curtis (Australian National University): “‘The Voice of Nature’: Conservation in Nineteenth Century England” ii. Ren Pepitone (Johns Hopkins University): “‘Common People in the Temple Gardens’: Regulating Space in the Metropolitan Center” iii. Terry Park (Miami University): “De/militarized Garden of Feeling: Jihae Hwang’s Quiet Time: DMZ Forbidden Garden” iv. Chair/Comment: Douglas Mao (Johns Hopkins University) ii. The Nation in Print: Text, Image, and Readership in Early Modern Britain Salon B i. Melissa Reynolds (Rutgers University): “Icons and Almanacs: Visual Practice and Non-Elite Book Culture in Late Medieval and Early Modern England” ii. Jessica Keene (Johns Hopkins University): “‘Certain most godly, fruitful, and comfortable letters’: Prison Letters, Protestantism, and Gender in Reformation England” iii. Joshua Tavenor (Wilfred Laurier University): “When Words are not Enough: the Promotion of Cuper’s Cove, Newfoundland in Seventeenth-century England” iv. Chair/Comment: Mary Fissell (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) iii. Charity and Commerce Interwoven in the British Empire Salon C i. Amanda Moniz (National History Center): “White’s Ventilator, or How the Lifesaving Cause Aided Abolition and the Slave Trade” ii. Karen Sonnelitter (Siena College): “Financing Improvement: Funding Charity in Eighteenth-Century Ireland” iii. Karen Auman (Brigham Young University): “For Faith and Profit: German Lutherans and the British Empire” iv. -

Surnames in Bureau of Catholic Indian

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Montana (MT): Boxes 13-19 (4,928 entries from 11 of 11 schools) New Mexico (NM): Boxes 19-22 (1,603 entries from 6 of 8 schools) North Dakota (ND): Boxes 22-23 (521 entries from 4 of 4 schools) Oklahoma (OK): Boxes 23-26 (3,061 entries from 19 of 20 schools) Oregon (OR): Box 26 (90 entries from 2 of - schools) South Dakota (SD): Boxes 26-29 (2,917 entries from Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records 4 of 4 schools) Series 2-1 School Records Washington (WA): Boxes 30-31 (1,251 entries from 5 of - schools) SURNAME MASTER INDEX Wisconsin (WI): Boxes 31-37 (2,365 entries from 8 Over 25,000 surname entries from the BCIM series 2-1 school of 8 schools) attendance records in 15 states, 1890s-1970s Wyoming (WY): Boxes 37-38 (361 entries from 1 of Last updated April 1, 2015 1 school) INTRODUCTION|A|B|C|D|E|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|Q|R|S|T|U| Tribes/ Ethnic Groups V|W|X|Y|Z Library of Congress subject headings supplemented by terms from Ethnologue (an online global language database) plus “Unidentified” and “Non-Native.” INTRODUCTION This alphabetized list of surnames includes all Achomawi (5 entries); used for = Pitt River; related spelling vartiations, the tribes/ethnicities noted, the states broad term also used = California where the schools were located, and box numbers of the Acoma (16 entries); related broad term also used = original records. Each entry provides a distinct surname Pueblo variation with one associated tribe/ethnicity, state, and box Apache (464 entries) number, which is repeated as needed for surname Arapaho (281 entries); used for = Arapahoe combinations with multiple spelling variations, ethnic Arikara (18 entries) associations and/or box numbers.