Europe. a Beautiful Idea?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U-Raad Wil Discussie Over Minor

“Met goed ontwikkelde doelen en feedback ben je een heel eind” Nieuws/3 Onderzoek/6 Cultuur/9 12 februari 2004 / jaargang 46 /3 Hogeschool: university? /5 Bindend studieadvies rukt op /9 Singers/songwriters gezocht /10 Snelle ‘adjes’ trekken /12 Motor-fiets Informatie- en opinieblad van de Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. Redactie telefoon 040-2472961 fax 040-2456033 e-mail [email protected] In ‘t kort Geen Cursor U-raad wil In de carnavalsweek ver- schijnt er geen Cursor. Nummer 23 verschijnt op discussie donderdag 4 maart. Verbod adver- tenties andere over minor universiteiten De universiteitsraad wil er wél de mogelijkheid Het Nijmeegse College van Bestuur heeft het uni- met het College van voor de keuze van een vrije versiteitsblad Vox Bestuur nog eens goed minor, maar het moet geen verboden wervingsadver- praten over de invulling pretpakket of onsamen- tenties voor masterstu- van de minor in het toe- hangend zooitje van denten van andere univer- komstige systeem van colleges worden. De exa- siteiten op te nemen. Zo flexibele bachelors. De mencommissie gaat hier wil men proberen universiteit wil beperkin- op toezien.” bachelors zoveel mogelijk gen stellen aan deze in- te laten doorstromen naar vulling, maar met name Afspraken de éigen masteroplei- studentenfractie PF pleit Studentenfractie Groep- dingen. Dit terwijl de voor meer keuzevrijheid. één benadrukt dat het CvB Katholieke Universiteit zich heeft gecommitteerd Nijmegen zelf wel met In de flexibele bachelor aan het Sectorplan “waarin haar opleidingen ad- kunnen studenten straks het major-minorsysteem is verteert in andere univer- een deel van hun opleiding opgenomen zonder dat er siteitsbladen. Prof.dr. zelf invullen: de minor. -

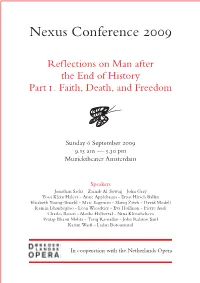

Nexus Conference 2009

Nexus Conference 2009 Reflections on Man after the End of History Part i . Faith, Death, and Freedom Sunday 6 September 2009 9.15 am — 5.30 pm Muziektheater Amsterdam Speakers Jonathan Sacks - Zainab Al-Suwaij - John Gray Yossi Klein Halevi - Anne Applebaum - Ernst Hirsch Ballin Elisabeth Young-Bruehl - Marc Sageman - Slavoj Žižek - David Modell Ramin Jahanbegloo - Leon Wieseltier - Eva Hoffman - Pierre Audi Charles Rosen - Moshe Halbertal - Nina Khrushcheva Pratap Bhanu Mehta - Tariq Ramadan - John Ralston Saul Karim Wasfi - Ladan Boroumand In cooperation with the Netherlands Opera Attendance at Nexus Conference 2009 We would be happy to welcome you as a member of the audience, but advance reservation of an admission ticket is compulsory. Please register online at our website, www.nexus-instituut.nl, or contact Ms. Ilja Hijink at [email protected]. The conference admission fee is € 75. A reduced rate of € 50 is available for subscribers to the periodical Nexus, who may bring up to three guests for the same reduced rate of € 50. A special youth rate of € 25 will be charged to those under the age of 26, provided they enclose a copy of their identity document with their registration form. The conference fee includes lunch and refreshments during the reception and breaks. Only written cancellations will be accepted. Cancellations received before 21 August 2009 will be free of charge; after that date the full fee will be charged. If you decide to register after 1 September, we would advise you to contact us by telephone to check for availability. The Nexus Conference will be held at the Muziektheater Amsterdam, Amstel 3, Amsterdam (parking and subway station Waterlooplein; please check details on www.muziektheater.nl). -

Patient Safety in Practice HOPE - European Hospital and Healthcare Federation

Patient safety in practice HOPE - European Hospital and Healthcare Federation Patient safety in practice How to manage risks to patient safety and quality in European healthcare Patient safety in practice December 2013 1 HOPE - European Hospital and Healthcare Federation REPORT ON HOPE AGORA The Hague 11-12 June 2013 Patient safety in practice December 2013 2 HOPE - European Hospital and Healthcare Federation CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 - 5 2. PATIENT SAFETY INITIATIVES 6 2.1. AT NATIONAL LEVEL 6 - 7 2.2. AT LOCAL AND HOSPITAL LEVEL 8 2.2.1. Communication tools for patiens 8 2.2.2. Organisation 9 2.2.3. Risk management 10 - 11 2.2.4. Patient safety tools 12 - 15 2.2.5. Involvement of patients and professionals 16 - 17 3. COUNTRY INFORMATION AUSTRIA 18 - 19 BELGIUM 20 DENMARK 21 ESTONIA 22 FINLAND 23 - 24 FRANCE 25 - 26 GERMANY 27 - 28 GREECE 29 HUNGARY 30 LATVIA 31 LITHUANIA 32 MALTA 33 NETHERLANDS 34 POLAND 35 PORTUGAL 36 - 37 SLOVENIA 38 SPAIN 39 SWEDEN 40 SWITZERLAND 41 UNITED KINGDOM 42 - 43 FOOTNOTES 44 Patient safety in practice December 2013 3 HOPE - European Hospital and Healthcare Federation 1. INTRODUCTION From 10 to 12 June 2013, HOPE held its Agora in The Hague (Netherlands), concluding the 32nd HOPE Exchange Programme, a 4-week training period intended for hospital and healthcare professionals with managerial responsibilities. “Patient safety in practice. How to manage risks to patient safety and quality in European healthcare” was the topic of HOPE Exchange Programme 2013. The final evaluation meeting of the HOPE Exchange Programme was preceded by a conference on this theme on 11 June, organised by the Dutch Hospitals Association (NVZ) and the Dutch Federation of University Medical Centres (NFU), in collaboration with HOPE. -

Why the Dutch Must Win Hearts and Minds by Jan Melissen

Clingendael Commentary March 14, 2008 Why the Dutch must win hearts and minds By Jan Melissen Geert Wilders, the farright Dutch member of parliament who has made an antiKoran film called Fitna (Arabic for chaos), is putting exceptional pressure on his country's political elite. Mr Wilders, who likened the Koran to Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf, is the Netherlands' best known politician throughout the Islamic world. Fitna has not yet been shown. However, burning Dutch and Danish flags in Afghanistan and crisis preparations in The Hague and Brussels indicate that this is already a big issue, and the film is a point of discussion at this week's European summit. The maverick politician is determined to broadcast his Islamophobic ideas this month. Jan Peter Balkenende, prime minister, has publicly acknowledged that he has a crisis on his hands. The Dutch government cannot be blamed for focusing on the immediate threat, but it must also reflect on the longterm issue of the Netherlands' international reputation. The consequences of this affair will be different policy at a time when there is decreasing from those of the Danish cartoon incident, but confidence in government. Moreover, this is hardly reassuring. Diplomacy is the art of international cultural policy has not kept up with smoothing out such matters, but it is hard to the times. Cultural diplomacy is not only about defend oneself against potential hate campaigns, presenting a country's culture and improving its violence against citizens overseas or a image abroad. It is, first and foremost, an spontaneous boycott of products. -

Islamisation in Policy Documents

Islamisation in Policy Documents A digital historical research on migration and integration policies in the Netherlands between 1994 and 2006 Neel van Roessel | Master’s Thesis History of Society Masther’s Thesis Neel van Roessel Student number: 486398 Email: [email protected] Supervisor: prof.dr. Dick Douwes Second reader: prof.dr. Alex van Stipriaan Luiscius Rotterdam, July 04, 2019 MA Global History and International Relations Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam Cover artwork: New Dutch Views #24 (2019) Artist: Marwan Bassiouni, Italian-American, Egyptian background, currently residing in the Netherlands. The artwork on the cover is part of a photoseries that captures the Dutch landscapes through the windows of mosques. ‘New Dutch Views is a symbolic portret of his double cultural background which shows that a new Western-Islamic identity is developing.’1 1 “New Dutch Views,” Fotomuseum Den Haag, March 22, 2019, http://www.fotomuseumdenhaag.nl/nl/tentoonstellingen/new-dutch-views. 2 Table of Contents List of figures and abbreviations 4 Introduction 5 1. Theory and Method 10 1.1 Theoretical concepts 10 1.2 Method 17 2. Historiography 23 3. Developments and incidents in migration and integration debates 35 3.1 Policy frameworks 1960s to 1990 36 3.2 Socio-economic participation (1990s) 40 3.3 Socio-cultural adjustment (after 2000) 49 3.4 Conclusion 56 4. Distant reading analysis policy of documents 60 4.1 Selection sources distant reading 60 4.2 Islam and Muslim word frequencies 63 4.3 Islam and Muslim word collocations 65 4.4 Conclusion 71 5. Close reading analysis of policy documents 73 5.1 Selection sources close reading 74 5.2 Common topics 75 5.3 Other documents 81 5.4 Conclusion 85 Conclusion 88 Parliamentary policy documents 93 Bibliography 95 Appendix 1 - List of policy documents for distant reading 104 Appendix 2 – Stopwords list 112 Appendix 3 – Word collocations of all years 116 3 List of figures and abbreviations Figure 1: Timeline, Reports, Developments and Incidents. -

The European Council — 50 Years of Summit Meetings (December 2011)

The European Council — 50 years of summit meetings (December 2011) Caption: This brochure, produced by the General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union, looks back at the history of the European Council from the first summit in Paris in 1961 to the transformation of the Council into an institution by the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009. It also includes a full list of all the meetings of the European Council. Source: General Secretariat of the Council, The European Council – 50 years of summit meetings. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012. 23 p. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/librairie/PDF/QC3111406ENC.pdf. Copyright: (c) European Union URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/the_european_council_50_years_of_summit_meetings_dece mber_2011-en-2d6c1430-1baf-4879-ada8-89065f8f009a.html Last updated: 25/11/2015 1/29 EUROPEAN COUNCIL EN The European Council 50 years of summit meetings GENERAL SECRETARIAT COUNCIL THE OF ARCHIVE SERIES ARCHIVE DECEMBER 2011 2/29 Notice h is brochure is produced by the General Secretariat of the Council; it is for information purposes only. For any information on the European Council and the Council, you can consult the following websites: http://www.european-council.europa.eu http://www.consilium.europa.eu or contact the Public Information Department of the General Secretariat of the Council at the following address: Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat 175 1048 Bruxelles/Brussel BELGIQUE/BELGIË Tel. +32 22815650 Fax +32 22814977 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/infopublic More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. -

Vijftig Jaar Advies En Overleg Over Consumentenzaken Rug 6 Mm [email protected] 070 3499 499 499 3499 070

rug 6 mm Vijftig jaar advies en overleg over consumentenzaken over advies en overleg Vijftig jaar 50 JAAR CCA | 2015 Vijftig jaar advies en overleg over consumentenzaken SOCIAAL-ECONOMISCHE RAAD Bezuidenhoutseweg 60 Postbus 90405 2509 LK Den Haag T 070 3499 499 E [email protected] www.ser.nl © 2015, Sociaal-Economische Raad SOCIAAL-ECONOMISCHE RAAD rug 6 mm Vijftig jaar advies en overleg over consumentenzaken 50 JAAR CCA | 2 50 JAAR CCA | 3 Inhoudopgave Voorwoord 5 Mariëtte Hamer De smalle lijn tussen beschermen en betuttelen 7 Barbara Baarsma SER en CCA: een halve eeuw wisselwerking 17 Marko Bos Vijftig jaar SER consumentenoverleg: het smaakt naar meer 31 Thom van Mierlo Oude sporen van tweezijdige zelfregulering: branches en huisvrouwen in de jaren vijftig en zestig 65 Thom van Mierlo Klachtencommissie Zuivelhandel – Eén kan er maar de eerste zijn 75 Thom van Mierlo Prijsinformatie: al vroeg een overheidsambitie voor de consument 85 Pieter Oudshoorn Voorzitters CCA en SER CZ 93 Tijdlijn SER en consumentenbeleid 94 Auteurs 103 50 JAAR CCA | 2 50 JAAR CCA | 3 50 JAAR CCA | 4 50 JAAR CCA | 5 Voorwoord De Commissie voor Consumentenvraagstukken van de SER bestaat 50 jaar. Een mooie aanleiding om terug en vooruit te blikken op het werkterrein van deze commissie – de CCA – en op haar bijzondere positie binnen de SER. Deze bundel kan u daarbij informe- ren en inspireren. Er zijn drie goede redenen voor het voeren van een consumentenbeleid. De eerste is – vanouds – het versterken van de positie van de consument. Voorlichting en bescher- ming gaan daarbij vaak hand in hand. -

Het Hof Van Brussel of Hoe Europa Nederland Overneemt

Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt Arendo Joustra bron Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt. Ooievaar, Amsterdam 2000 (2de druk) Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/jous008hofv01_01/colofon.php © 2016 dbnl / Arendo Joustra 5 Voor mijn vader Sj. Joustra (1921-1996) Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt 6 ‘Het hele recht, het hele idee van een eenwordend Europa, wordt gedragen door een leger mensen dat op zoek is naar een volgende bestemming, die het blijkbaar niet in zichzelf heeft kunnen vinden, of in de liefde. Het leger offert zich moedwillig op aan dit traagkruipende monster zonder zich af te vragen waar het vandaan komt, en nog wezenlijker, of het wel bestaat.’ Oscar van den Boogaard, Fremdkörper (1991) Arendo Joustra, Het hof van Brussel of hoe Europa Nederland overneemt 9 Inleiding - Aan het hof van Brussel Het verhaal over de Europese Unie begint in Brussel. Want de hoofdstad van België is tevens de zetel van de voornaamste Europese instellingen. Feitelijk is Brussel de ongekroonde hoofdstad van de Europese superstaat. Hier komt de wetgeving vandaan waaraan in de vijftien lidstaten van de Europese Unie niets meer kan worden veranderd. Dat is wennen voor de nationale hoofdsteden en regeringscentra als het Binnenhof in Den Haag. Het spel om de macht speelt zich immers niet langer uitsluitend af in de vertrouwde omgeving van de Ridderzaal. Het is verschoven naar Brussel. Vrijwel ongemerkt hebben diplomaten en Europese functionarissen de macht op het Binnenhof veroverd en besturen zij in alle stilte, ongezien en ongecontroleerd, vanuit Brussel de ‘deelstaat’ Nederland. -

RUG/DNPP/Repository Boeken/De Stranding/11. De Stranding

227 HOOFDSTUK II De stranding Hoe het CDA de verkiezingen, de macht en de kroonprins verloor Diep in de nacht van donderdag 7 op vrijdag 8 april loopt Frits Wester in de wandelgangen van de Tweede Kamer zijn collega Jan Schinkelshoek tegen het lijf. Zijn voormalige baas, nu pers- voorlichter van minister Hirsch Baum, heeft een vraag. 'Waar benje morgen?' 'Thuis', antwoordt Wester. Op vrijdag verga- dert de Kamer niet, en hij wil een vrije ochtend nemen. 'Houje maar liever beschikbaar', zegt Schinkelshoek. 'Er staat misschien iets vervelends te gebeuren; ik kanje alleen niet vertellen wat.' Het is geen toeval dat de twee voorlichters op dat tijdstip nog in de Kamer zijn. Vanaf twee uur 's middags heeft het parlement gedebatteerd over de IRT-zaak, waarbij zowel Hirsch Ballin als minister Van Thijn zware kritiek te verduren kregen. In de loop van de avond is een motie van afkeuring ingediend tegen Hirsch BalEn. Hij is als minister vanjustitie medeverantwoordelijkvoor de falende controle op het Interregionale Recherche Team, waarover inj anuari nogal wat commotie ontstond. Het is nu drie uur. Zojuist heeft de Kamer die motie verworpen. De CDA-frac- tie heeft serieus overwogen haar te steunen en Hirsch Ballin te laten vallen, maar heeft daar op het laatste moment van afgezien. Wel komt er een parlementair onderzoek naar de opsporingsme- thoden die de recherche gebruikt in de strijd tegen de zware mis- daad, omdat er ernstige twijfel is gerezen over de toelaatbaarheid daarvan. Toen Hirsch BalEn en Van Thijn twee weken eerder, Op zi maart, een onderzoeksrapport over de IRT-zaak ontvin- gen, was meteen al duidelijk dat deze zaak ernstige politieke con- sequenties kon hebben. -

1 Introductie

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Innovatiepolitiek: Een reconstructie van het innovatiebeleid van het ministerie van Economische Zaken van 1976 tot en met 2010 Velzing, E.-J. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Velzing, E-J. (2013). Innovatiepolitiek: Een reconstructie van het innovatiebeleid van het ministerie van Economische Zaken van 1976 tot en met 2010. Eburon. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:29 Sep 2021 1 Introductie Een directeur-generaal van het ministerie van Economische Zaken bezoekt vertegenwoordigers van bedrijven. Het zijn toonaangevende namen. Voor vandaag is zijn opdracht het nieuwe innovatiebeleid van de minister uit te leggen. Hij meldt zich en voelt een lichte spanning. Zal de nieuwe insteek wel goed vallen? Sluit het aan bij hun wensen? Is de voorbereide presentatie overtuigend? Zelf heeft hij eerlijk gezegd nog gerede twijfels. -

Onderzoeksrapport Vrouwen in De Media 2009

Onderzoeksrapport Vrouwen in de Media 2009 Janneke Boer (deel 1) Jolanda van Henningen (deel 2) Met reacties van o.a.: Birgit Donker Marga Miltenburg Neelie Kroes Pia Dijkstra Rita Verdonk Samira Bouchibti november 2009 Onderzoek Vrouwenindemedia.nl 2009 1 Voorwoord Het éne onderzoek na het andere brengt naar voren wat eigenlijk ook al met het blote oog te zien is. In de media komen vrouwen minder vaak aan het woord dan mannen. De Nederlandse bevolking bestaat voor 50,5 procent uit vrouwen. In de media is slechts één op de vijf mensen aan het woord een vrouw. In 2000 zei toenmalige staatssecretaris van Cultuur Rick van der Ploeg het al in de Volkskrant: “De publieke omroep moet een betere afspiegeling vormen van de Nederlandse samenleving”. Helaas is er ook na 2000 weinig veranderd. Bij de publieke omroep en bij de andere media lijkt de tijd stil te staan. Inderdaad, er zitten meer mannen in de top van het Nederlandse zakenleven, maar laten we nou eerlijk zijn. Ook als het gaat om andere deskundigen waarbij er wel degelijk een gelijke verhouding is zijn het toch vaker de mannen die in de media aan het woord zijn. Laten we onszelf niet langer voor de gek houden en kijken naar het potentieel aan vrouwelijke deskundigheid. Scheef of niet? Ik heb van redacties wel eens de vraag gekregen of die verhouding wel echt zo scheef is als ik altijd verkondig. Ook zijn er terecht vragen gesteld of het wel de schuld van de media is dat er geen realistische afspiegeling van de maatschappij wordt getoond. -

Remarks with Prime Minister Jan Peter Balkenende at a Youth

Administration of George W. Bush, 2005 / May 8 777 proud to serve with you. Today I’m honored lands today, because on the 6th of May— to deliver the thanks of the American people. that’s what we call our Liberation Day—and Sixty years ago, on the 7th of May, the we always think about our freedom. And at world reacted with joy and relief at the defeat your last event, you said a lot about impor- of fascism in Europe. The next day, General tance of freedom and democracy, and you Dwight D. Eisenhower announced that ‘‘his- realize what Americans meant for the Euro- tory’s mightiest machine of conquest has pean countries after the Second World War. been utterly destroyed.’’ Yet the great de- During the Second World War, your people mocracies soon found that a new mission had were here, but after, you helped us. come to us, not merely to defeat a single dic- And it’s very important that you’re here tator but to defeat the idea of dictatorship today and that you’ll have the meeting in on this continent. Through the decades of Margraten. It’s so important to be there and that struggle, some endured the rule of ty- also for us to show our respect and to say rants; all lived in the frightening shadow of thanks for what all the Americans have done war. Yet because we lifted our sights and held for the Netherlands. firm to our principles, freedom prevailed. We already had a breakfast meeting. We Now, ladies and gentlemen, the freedom talked about some very important issues.