Creating Kabīr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kabir: Towards a Culture of Religious Pluralism

198 Dr.ISSN Dharam 0972-1169 Singh Oct., 2003–Jan. 2003, Vol. 3/II-III KABIR: TOWARDS A CULTURE OF RELIGIOUS PLURALISM Dr. Dharam Singh Though globalization of religion and pluralistic culture are more recent terms, the human desire for an inter-faith culture of co- existence and the phenomenon of inter-faith encounters and dialogues are not entirely new. In the medieval Indian scenario we come across many such encounters taking place between holy men of different and sometimes mutually opposite religious traditions. Man being a social creature by nature cannot remain aloof from or indifferent to what others around him believe in, think and do. In fact, to bring about mutual understanding among people of diverse faiths, it becomes necessary that we learn to develop appreciation and sympathy for the faith of the others. The medieval Indian socio-religious scene was dominated by Hinduism and Islam. Hinduism has been one of the oldest religions of Indian origin and its adherents in India then, as even today, constituted the largest majority. On the other hand, Islam being of Semitic origin was alien to India until the first half of the 7th century when the “first contacts between India and the Muslim world were established in the South because of the age- old trade between Arabia and India.”1 However, soon these traders tuned invaders when Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni led a long chain of invasions on India and molestation of Indian populace. To begin with, they came as invaders, plundered the country-side and went back, but soon they settled as rulers. -

Year 6 - PACK 1 - Week 4 – Week Beginning 22.06.2020

Year 6 - PACK 1 - Week 4 – Week Beginning 22.06.2020 Monday Reading – ‘Percy Jackson and the Greek Gods’ – Rick Riordan Writing – Instructional Writing Maths – Converting Fractions to Percentages Thematic – Transition – My Positivity Profile Tuesday Reading – ‘Percy Jackson and the Greek Gods’ – Rick Riordan Writing – Poetry – imperative verbs Maths – Equivalent Fractions, Decimals and Percentages Science – Animals including humans – Session 4 – The Digestive System Wednesday Reading – ‘Percy Jackson and the Greek Gods’ – Rick Riordan Writing – Instructional Writing – Colons and semi-colons Maths – Ordering Fractions, Decimals and Percentages PE – PE – Circuit Exercises for Healthy Hearts Thursday Reading – ‘Percy Jackson and the Greek Gods’ – Rick Riordan Writing – Recipe Drafting Maths – Percentages of Amounts RE - RE – The Sikh Festival of Vaisakhi Friday Reading – ‘Percy Jackson and the Greek Gods’ – Rick Riordan Writing – Recipe Editing Maths – Fractions, decimals and percentages assessment Music - Music – Virtual Percussion and Notation This timetable is flexible. Some days will be more productive than others. We ask that you do the core subjects (reading, writing, maths) daily, and then balance the foundation subjects as suits you. You may find that doing all of the days work in one go works best (remember to take a short break, though) or splitting it into morning and afternoon suits you better. If you are unable to complete everything then do not worry. Do your best and that will be good enough. Remember the assembly on routines – try to start at the same time every day, in a quiet place if possible. Have a clear plan for the day. There will be some QR codes (barcodes) that you will be able to scan. -

Changing the World Through Social Entrepreneurship: Apply Now!

Changing the world through social entrepreneurship: apply now! Do you have a world-changing idea? Apply with your business case for your chance to win a spot at the WE Social Incubation Hub! We believe that young people have the power to change the world—and the WE Social Entrepreneurship Program provides the tools to make that happen. This 12-part program at the WE Global Learning Center in Toronto empowers young social entrepreneurs like you to develop and launch your own social enterprise, giving you access to helpful resources, mentorship and connections with like-minded individuals. Whether it’s starting a non-profit or mobilizing your friends to contribute to social justice, this program helps you take the next steps to making your world-changing idea a reality. Apply today by answering Program details these questions: The WE Social Entrepreneurship Program is run by trained WE staff, including experienced educators and leadership facilitators. The • What kind of social impact do you want to create? program features sessions run by industry experts in leadership, • How will it affect the people in your community? business and social entrepreneurship. • What is your social project, product or innovation? The program is a 12-part learning experience for youth aged 14 to 19, • How will your project remain sustainable? taking place at the WE Global Learning Center. The winning finalists will have the opportunity to participate in this transformative program • What aspect of your project would you like support for? and become an expert on the issue they feel passionate about. Apply now! Apply online today with your business case here. -

Hinduism and Social Work

5 Hinduism and Social Work *Manju Kumar Introduction Hinduism, one of the oldest living religions, with a history stretching from around the second millennium B.C. to the present, is India’s indigenous religious and cultural system. It encompasses a broad spectrum of philosophies ranging from pluralistic theism to absolute monism. Hinduism is not a homogeneous, organized system. It has no founder and no single code of beliefs; it has no central headquarters; it never had any religious organisation that wielded temporal power over its followers. Hinduism does not have a single scripture as the source of its various teachings. It is diverse; no single doctrine (or set of beliefs) can represent its numerous traditions. Nonetheless, the various schools share several basic concepts, which help us to understand how most Hindus see and respond to the world. Ekam Satya Viprah Bahuda Vadanti — “Truth is one; people call it by many names” (Rigveda I 164.46). From fetishism, through polytheism and pantheism to the highest and the noblest concept of Deity and Man in Hinduism the whole gamut of human thought and belief is to be found. Hindu religious life might take the form of devotion to God or gods, the duties of family life, or concentrated meditation. Given all this diversity, it is important to take care when generalizing about “Hinduism” or “Hindu beliefs.” For every class of * Ms. Manju Kumar, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, Delhi University, Delhi. 140 Origin and Development of Social Work in India worshiper and thinker Hinduism makes a provision; herein lies also its great power of assimilation and absorption of schools of philosophy and communities of people, (Theosophy, 1931). -

Year 4 - PACK 1 - Week 6 – Week Beginning 08.02.2021

Year 4 - PACK 1 - Week 6 – Week Beginning 08.02.2021 Monday Reading – ‘The Romans’ Writing – Inverted commas in direct speech Handwriting Practice Maths – The 7 Times Table and Division Facts Thematic – How did the Romans conquer Britain? Tuesday Reading – ‘The Romans’ Writing – Apostrophes for contractions Spelling Practice Maths – 11- and 12-times table Science – How do we construct a food chain? Wednesday Reading – ‘The Romans’ Writing – Apostrophes for possession Handwriting Practice Maths – Multiplying 3 numbers PE - PE With Joe / 10 Minute Shake Up Disney Games Computing - Learn to Code with Harry Potter Thursday Reading – ‘The Romans’ Writing – Using parenthesis to add extra information Spelling Practice Maths – Finding Factor Pairs PSHE - Being Kind to yourself and taking time to be calm RE - The Sikh Festival of Vaisakhi Friday Reading – ‘The Romans’ Writing – Editing practice Handwriting Practice Maths – Multiplication and division assessment Spanish - Greetings This timetable is flexible. Some days will be more productive than others. We ask that you do the core subjects (reading, writing, maths) daily, and then balance the foundation subjects as suits you. You may find that doing all of the days work in one go works best (remember to take a short break, though) or splitting it into morning and afternoon suits you better. If you are unable to complete everything then do not worry. Do your best and that will be good enough. Remember the assembly on routines – try to start at the same time every day, in a quiet place if possible. Have a clear plan for the day. There will be some QR codes (barcodes) that you will be able to scan. -

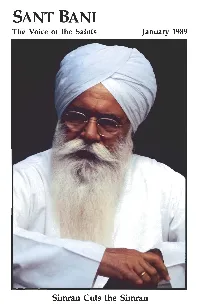

Simran Cuts the Simran PHOTOCREDITS Front Cover, Pp

The Voice of the Saints January 1989 I Simran Cuts the Simran PHOTOCREDITS Front cover, pp. 17, 25, Jonas Gerard; p. 2, back cover, Charlie Boynton. The quote on the back cover is from Sant Ji's question and answer session which begins on page 26. SANTBANI volume thirteen number seven The Voice of the Saints January 1989 FROM THE MASTERS The Pain of Separation 3 Sant Ajaib Singh Ji January 11, 1987 Sant Ji's Message for Christmas 16 Sant Ajaib Singh Ji and the New Year How to Develop the Attributes 18 Sant Kirpal Singh Ji of the Master from Morning Talks Simran Cuts the Simran 26 Sant Ajaib Singh Ji April 3, 198.5 OTHER FEATURES We Are Immensely Lucky Souls 12 Silvia Gelbard a personal experience SANT BANIIThe Voice of the Saints is published periodically by Sant Bani Ashram, Inc., Sanbornton, N.H., U.S.A., for the purpose of disseminating the teachings of the living Master, Sant Ajaib Singh Ji, of His Master, Param Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, and of the Masters who preceded them. Editor: Richard Shannon, with kind assistance from: Edythe Grant, Rita Fahrkopf, and Susan Shannon. Annual subscription rate in U.S. $24.00 Individual issues $2.50. Back issues $2.50. Foreign and special mailing rates available on request. All checks and money orders should be made payable to Sant Bani Ashram, and all payments from outside the U.S. should be on an International Money Order or a check drawn on a New York bank (with a micro-encoded number). -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Download Registration Number for Offline

To download the Admit Card please enter your Registration Number and Date of Birth in the format (yyyy-mm-dd). Registration Number Name of Candidate Course1 Course2 Father Name CUJET/2012/000001 JAI SHREE BHARDWAJ M.Tech. Nano Technology M.Tech. Energy Engineering KUMAR SUNDRAM BHARDWAJ CUJET/2012/000002 DHRAMENDAR KUMAR M.B.A. M.A. International Relations Harinath CUJET/2012/000003 KAJOL M.Tech. Nano Technology M.Tech. Energy Engineering SUMAN KUMAR VERMA CUJET/2012/000004 Ashutosh Kumar M.Tech. Energy Engineering M.Tech. Water Engineering & Management Madan Murari Pandey CUJET/2012/000005 RAVI VIKASH TIRKEY M.B.A. M.A. Mass Communication LEO ABHAY TIRKEY CUJET/2012/000006 Ms. SAYANTANI MANDAL M.Sc. Environmental Science Mr. NISITH RANJAN MANDAL CUJET/2012/000012 Mr OMKAR SHARAN MISHRA M.B.A. M.A. International Relations Mr KAMAL KUMAR MISHRA Mr ABHIRAM SHARAN CUJET/2012/000013 MISHRA M.Tech. Energy Engineering M.Sc. Applied Chemistry Mr KAMAL KUMAR MISHRA CUJET/2012/000014 Samatha Tejavath M.Sc. Applied Mathematics M.Tech. Nano Technology Nageswara Rao Tejavath CUJET/2012/000015 ASHUTOSH GUPTA M.Tech. Energy Engineering M.Tech. Water Engineering & Management A K GUPTA CUJET/2012/000017 Shahid Hussain Rahmatullah CUJET/2012/000019 RAJIV RANJAN M.B.A. M.A. Mass Communication SURYADEO SINGH CUJET/2012/000020 Amit Kumar M.B.A. M.A. Mass Communication Rahul Kumar CUJET/2012/000021 arman khan M.Tech. Nano Technology M.Tech. Water Engineering & Management arif khan CUJET/2012/000023 AMIT ANAND M.B.A. M.Tech. Nano Technology VEER PRASAD MAHTO CUJET/2012/000024 MOHIT MAYOOR M.Tech. -

Ritual and Reform in the Kabir Panth

1 RITUAL AND REFORM IN THE KABIR PANTH Peter Friedlander: La Trobe University [email protected] Introduction The Kabir Panth is a religious movement based on the teachings of the north Indian poet saint Kabir (1398-1518). This paper looks at the practice of rituals called chauka in the Kabir Panth and a campaign led by the leader of the Kabircaura branch of the Kabir Panth to abolish the chauka rituals. The paper starts by outlining the history of the Panth and the role of the chauka ritual in the practices of the branches of the Kabir Panth who follow the teachings of Kabir’s disciple Dharmdas. It then examines accounts of the life of Vivekdas, the leader of the Kabircaura branch of the Kabir Panth, and his arguments that the chauka ritual should be abandoned because it is a corrupt practice which is not based on the teachings of Kabir. I propose that the controversy over the practice of the chauka ritual reflects different branches of the Kabir Panth’s responses to modernity. The importance of this I suggest it that it shows how a religious movement can become divided into branches with some advocating conservative practices based on localised rituals at the same time as other branches can advocate reformist approaches based on establishing a universal global identity.1 1 This paper was presented to the 18th Biennial Conference of the Asian Studies Association of Australia in Adelaide, 5-8 July 2010. It has been peer reviewed via a double referee process and appears on the Conference Proceedings Website by the permission of the author who retains copyright. -

KRAKAUER-DISSERTATION-2014.Pdf (10.23Mb)

Copyright by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Benjamin Samuel Krakauer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor Charles Capwell Kaushik Ghosh Kathryn Hansen Robin Moore Sonia Seeman Negotiations of Modernity, Spirituality, and Bengali Identity in Contemporary Bāul-Fakir Music by Benjamin Samuel Krakauer, B.A.Music; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Dedication This work is dedicated to all of the Bāul-Fakir musicians who were so kind, hospitable, and encouraging to me during my time in West Bengal. Without their friendship and generosity this work would not have been possible. জয় 巁쇁! Acknowledgements I am grateful to many friends, family members, and colleagues for their support, encouragement, and valuable input. Thanks to my parents, Henry and Sarah Krakauer for proofreading my chapter drafts, and for encouraging me to pursue my academic and artistic interests; to Laura Ogburn for her help and suggestions on innumerable proposals, abstracts, and drafts, and for cheering me up during difficult times; to Mark and Ilana Krakauer for being such supportive siblings; to Stephen Slawek for his valuable input and advice throughout my time at UT; to Kathryn Hansen -

Name of the Centre : DAV Bachra No

Name of the Centre : DAV Bachra No. Of Students : 474 SL. No. Roll No. Name of the Student Father's Name Mother's Name 1 19002 AJAY ORAON NIRMAL ORAON PATI DEVI 2 19003 PUJA KUMARI BINOD PARSAD SAHU SUNITA DEVI 3 19004 JYOTSANA KUMARI BINOD KUMAR NAMITA DEVI 4 19005 GAZAL SRIVASTVA BABY SANTOSH KUMAR SRIVASTAVA ASHA SRIVASTVA 5 19006 ANURADHA KUMARI PAPPU KUMAR SAH SANGEETA DEVI 6 19007 SUPRIYA KUMARI DINESH PARSAD GEETA DEVI 7 19008 SUPRIYA KUMARI RANJIT SHINGH KIRAN DEVI 8 19009 JYOTI KUMARI SHANKAR DUBEY RIMA DEVI 9 19010 NIDHI KUMARI PREM KUMAR SAW BABY DEVI 10 19011 SIMA KUMARI PARMOD KUMAR GUPTA SANGEETA DEVI 11 19012 SHREYA SRIVASTAV PRADEEP SHRIVASTAV ANIMA DEVI 12 19013 PIYUSH KUMAR DHANANJAY MEHTA SANGEETA DEVI 13 19014 ANUJ KUMAR UPENDRA VISHWAKARMA SHIMLA DEVI 14 19015 MILAN KUMAR SATYENDRA PRASAD YADAV SHEELA DEVI 15 19016 ABHISHEK KUMAR GUPTA SANT KUMAR GUPTA RINA DEVI 16 19017 PANKAJ KUMAR MUKESH KUMAR SUNITA DEVI 17 19018 AMAN KUMAR LATE. HARISHAKAR SHARMA RINKI KUMARI 18 19019 ATUL RAJ RAJESH KUMAR SATYA RUPA DEVI 19 19020 HARSH KUMAR SHAILENDRA KR. TIWARY SNEHLATA DEVI 20 19021 MUNNA THAKUR HIRA THAKUR BAIJANTI DEVI 21 19022 MD.FARID ANSARI JARAD HUSSAIN ANSARI HUSNE ARA 22 19023 MD. JILANI ANSARI MD.TAUFIQUE ANSARI FARZANA BIBI 23 19024 RISHIKESH KUNAL DAMODAR CHODHARY KAMLA DEVI 24 19025 VISHAL KR. DUBEY RAJEEV KUMAR DUBEY KIRAN DEVI 25 19026 AYUSH RANJAN ANUJ KUMAR DWIVEDI ANJU DWIVEDI 26 19027 AMARTYA PANDEY SATISH KUMAR PANDEY REENA DEVI 27 19028 SHIWANI CHOUHAN JAYPAL SINGH MAMTA DEVI 28 19029 SANDEEP KUMAR MEHTA -

The Ocean of Love'

7 The Ocean ofF Love' The Anurag Sear of Kabir THE OCEAN OF LOVE THE OCEAN OF LOVE The Ocean of Love The Anurlig Sagar of Kabir Translated and Edited under the direction of Sant Ajaib Singh Ji Sant Bani Ashram Sanbornton, New Hampshire Translated from the Braj by Raj Kumar Bagga with the assistance of Partap Singh and Kent Bicknell Edited with Introduction and Notes by Russell Perkins Illustrated by Michael Raysson First printing, 1982 Second printing, index added 1984 Third printing, 1995 ISBN: 0-89142-039-8 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 82-050369 Kal did the devotion on one foot (see page 23) Kabir and Dharam Das by Sant Ajaib Singh Ji ER SINCE the Almighty Lord started coming into this world Ein the form of the Saints, it has always happened that during a Saint's lifetime only a few people care to know about his life: where the Saint was born, how he used to live, what qualities he had, and why he came into this world. They don't care about all these things while the Saint is alive; but when the Saints leave this world, their incredible power and their teachings which change the lives of many people impress the people of the world, and only then-when the Saint is gone-do the people of the world start thinking about them and devoting themselves to them. So that is why, according to the understanding of the people, stories are told about the Saints. It is very difficult to find out much about the Mahatmas of the past-their birth, their place of birth, their parents, their early life, etc.