Costs of Taxing Sodium: a Lunch Meat Application1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partner with Carl Buddig & Company

Customizing Your Satisfaction Buddig is known for great-tasting meats, and delicious, handcrafted sausage that carries Getting the familiar Old Wisconsin name. Today we’re making a name for ourselves in customized products that meet an ever-increasing variety of specific requirements for customers like you. it right. We start with your needs… Partner with Carl Buddig & Company Experience makes the difference. And we have more than 60 years in the business of making Then show you the meats that best satisfy them, while meeting your great-tasting meat products. Imagine what that experience can do for you. portion size and pricing target needs. We offer: • A cross-functional team including marketing, R&D, sales and operations will work quickly to • Gluten-free, allergen-free, no-MSG-added items from our USDA- develop products and packaging that meet your needs inspected facilities • Our staff: Long-term, well-trained professionals with a real dedication to creating your solution • Quality lunch meats: Turkey, Chicken, Ham, Beef and Corned Beef. Reduced sodium formulations available • Over the years, we’ve built long-standing relationships with our customers by delivering beyond expectations – from the first inquiry to the final detail • Flame-grilled Chicken: Whole breasts or specialty cut, lightly seasoned or in specialty flavors like Southwest and Italian • Dedicated to customized solutions that add value • Shelf-stable Sausages: Small slices of Salami, Pepperoni and • Special pricing programs available to meet your needs Summer Sausages; -

Ham and Food Safety

United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service Food Safety Information PhotoDisc Ham and Food Safety ams: They can be fresh, cook-before-eating, cooked, picnic, and country types. There are so many kinds, Hand their storage times and cooking times vary. This background information serves to carve up the facts and make them easier to understand. Definition Hams may be fresh, cured, or cured-and-smoked. Ham is the cured leg of pork. Fresh ham is an uncured leg of pork. Fresh ham will bear the term “fresh” as part of the product name and is an indication that the product is not cured. “Turkey” ham is a ready-to-eat product made from cured thigh meat of turkey. The term “turkey ham” is always followed by the statement “cured turkey thigh meat.” The usual color for cured ham is deep rose or pink; fresh ham (which is not cured) has the pale pink or beige color of a fresh pork roast; country hams and prosciutto (which are dry cured) range from pink to a mahogany color. Hams are either ready to eat or not. Ready-to-eat hams include prosciutto and cooked hams; they can be eaten right out of the package. Fresh hams and hams that are only treated to destroy trichinae (which may include heating, freezing, or curing in the plant) must be cooked by the consumer before eating. Hams that must be cooked will bear cooking instructions and safe handling instructions. Hams that are not ready-to-eat, but have the appearance of ready-to-eat products, will bear a prominent statement on the principal display panel (label) indicating the product needs cooking, e.g., “cook thoroughly.” In addition, the label must bear cooking directions. -

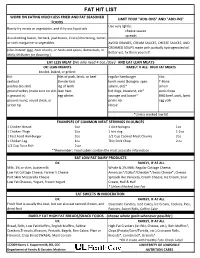

Fat Hit List

FAT HIT LIST WORK ON EATING MUCH LESS FRIED AND FAT SEASONED LIMIT YOUR "ADD-ONS" AND "ADD-INS" FOODS Use very lightly: Rarely fry meats or vegetables, and if fry use liquid oils cheese sauces spreads Avoid adding bacon, fat back, jowl bacon, Crisco/shortening, butter, or stick margarine to vegetables AVOID GRAVIES, CREAM SAUCES, CHEESE SAUCES, AND CREAMED SOUPS made with partially hydrogenated oil. [Use instead lean ham chunks, or herbs and spices, Butterbuds, or Better yet, fix them yourself. Molly McButter for flavoring ] EAT LESS MEAT (We only need 4-5oz./day ) AND EAT LEAN MEATS OK: LEAN MEANTS RARELY IF ALL: HIGH FAT MEATS broiled, baked, or grilled: fish filet of pork, lamb, or beef regular hamburger ribs seafood (tenderloin) lunch meat (bologna, span, T-Bone poultry (no skin) leg of lamb salami, etc)* sirloin ground turkey (make sure no skin lean ham hot dogs, brawurst, etc* pork chops is ground in) egg whites sausage and bacon* BBQ beef, pork, lamb ground round, round steak, or prime rib egg yolk sirloin tip ribeye *Unless marked low fat EXAMPLES OF COMMON MEAT SERVINGS IN OUNCES 1 Chicken Breast 3oz 1 slice bologna 1oz 1 Chicken Thigh 2oz 1 hot dog 1-2oz 1 Fast Food Hamburger 2oz 1/2 Cup Cooked Meat Chunks 2oz 1 Chicken Leg 1oz Thin Pork Chop 2 oz 1/2 Cup Tuna Fish 2 oz **Remember: Food Labels contain the most accurate information EAT LOW FAT DAIRY PRODUCTS OK RARELY, IF AT ALL Milk: 1% or skim, buttermilk Whole & 2% Milk, Regular Cottage Cheese, Low Fat Cottage Cheese, Farmer's Cheese American*/Colby*/Chedder*/Swiss Cheese*, -

Drink-Dine 2020VG.Pdf

Drink + Dine VISITDULUTH.COM/DINING P Designated Accessible Parking or Off-Street Parking E Accessible Entrance R Accessible Rest Rooms C Complete Facility Accessibility Pet Friendly Gluten Free Options Vegetarian Options AT SARA’S TABLE BLACK WATER LOUNGE BOWERY BROS. PUB CHESTER CREEK CAFE AT GREYSOLON 505 W Superior Street 1902 E 8th Street 231 E Superior Street Duluth, MN 55802 Duluth, MN 55812 Duluth, MN 55802 (218) 727-8981 (218) 724-6811 (218) 740-0436 bowerybrospub.com C astccc.net P E R C blackwaterlounge.com P E R C Bowery Brothers Pub is located in the Farm-to-table handmade food in the Black Water Lounge is Minnesota’s #1 Radisson Duluth Hotel and is a warm and university neighborhood. Espresso bar, martini lounge. With a full bar, hand- inviting place to enjoy freshly prepared pub beer, wine and cocktail bar. Lake view deck crafted cocktails, exquisite lounge food, live fare, specialty beers and friendly service. with dogs allowed. Homemade bread. jazz music and ladies’ night, Black Water is AE/DC/MC/V/CB/D High quality breakfast, lunch and dinner. the finest upscale martini bar with the best Vegetarian, vegan and gluten free options. happy hour specials in town! THE CADDY SHACK Organic garden. Responsible service. INDOOR GOLF & PUB Meeting room and wi-fi. Lots of parking. BLACK WOODS GRILL & BAR 2023 W Superior Street Everything is done with care. 2525 London Road Duluth, MN 55806 Duluth, MN 55812 (218) 624-7768 (218) 724-1612 caddyshackduluth.com blackwoods.com P E R C P E R C At Black Woods Grill & Bar, we’re The Northland’s Premier Indoor Golf & BELLISIO’S committed to providing Northern Shooting Facility with a Full Bar & Food for ITALIAN RESTAURANT Minnesota’s foremost dining experience. -

Take-Along Lunches

Take-along Lunches Take-along Lunches What goes in? More and more kids and adults pack lunches for Just as breakfast gets you through the morning, school or work. The portable lunch can satisfy the lunch will keep you alert throughout the afternoon. need for food and relaxation even in a relatively brief Hungry people have trouble concentrating on 30-minute lunch break. schoolwork or jobs and may not perform at their highest levels. A good lunch includes these parts: Why pack a take-along lunch? 1. Protein-containing food – Protein Economics: Pack-your-own lunches should be less comes in many forms including milk expensive than eating out, but if wise choices are not and milk products, meat, fish, cheese, made, they can be more expensive. This is especially eggs, nuts, beans and peanut butter. true for children who could eat lunch prepared as part Using leftovers to provide protein of the school lunch program. If the child’s take-along may require less preparation than lunch is made up of purchased packets of individual a sandwich. When milk is not the servings of food such as chips, cookies and puddings, beverage, cheese or yogurt may it may cost more than the cafeteria meal. provide calcium as well as protein. Adults with access to a company cafeteria also 2. Grains – Bread, cereal, rice or pasta may find it more expensive to carry a lunch. Cost can 3. Fruits be kept down by using leftovers. 4. Vegetables Nutrition: You can control the nutritional quality 5. Beverage – preferably milk of a lunch if you select, prepare and pack foods so for children they will be safe, flavorful and nutritious. -

Ham for the Holidays, December 2007

ISSUE VOLUME DECEMBER 4 16 2017 Hams, Hams, Hams Charts & Terms Ham It Up Ham for the HOLIDAYS Fresh, cook-before-eating, cooked, picnic, from smoldering fires, which gives added country types … knowing how to store and flavor and color to meat and slows the cook different hams can be quite confusing. development of rancidity. Not all smoked meat is smoked from smoldering fires. A Hams may be fresh, cured, or cured-and- popular process is to heat the ham in a smoked. Ham is the cured leg of pork. Fresh smoke house and generate smoke from ham is an uncured leg of pork. Fresh ham will atomized smoke flavor. bear the term "fresh" as part of its name and is an indication that the product is not cured. Quantity to Buy When buying a ham, estimate the size The usual color for cured ham is deep rose or needed according to the number of servings pink; fresh ham (which is not cured) has the the type of ham should yield: pale pink or beige color of a fresh pork roast. ¼ - ⅓ lb. per serving of boneless ham Hams are either ready to eat or not. Ready- ⅓ - ½ lb. of meat per serving of bone- to-eat hams include prosciutto and cooked in ham hams; they can be eaten out of the package. Hams that must be cooked will bear cooking Cooking or Reheating Hams instructions & safe handling methods. Both whole & half, cooked, vacuum-packaged hams packaged in federally inspected plants Hams that are not ready to eat, but have the & canned hams can be eaten cold just as they appearance of ready-to-eat products, will come from their packaging. -

3Rd Tri Lunch and Deli Meats Webinar Handout

LUNCH AND DELI MEATS IN THE CACFP Processed meats, such as deli meat and hot dogs, are products that may contain added liquids (such as water or broth) or other types of fillers to help enhance flavor and preserve or extend the product's shelf life. Are Processed Meats Creditable? Not every ingredient in processed meats is considered a Meat or Meat Alternate. In order to credit a lunch or deli meat, the composition of these products must be known so the correct portion can be served. To know the amount of a product that can be credited toward the Meat/Meat Alternate component, a Child Nutrition (CN) label or a Product Formulation Statement (PFS) may be needed. For example, one lunch meat variety may require 1.8 ounces of meat in order to credit as 1 ounce of Meat/Meat Alternate, whereas another may need 2.4 ounces of meat to credit as 1 ounce of the Meat/Meat Alternate component. Some processed meats have a Standard o f Identity. These meat products have crediting information that can be found in the USDA Food Buying Guide. As long as they do not contain by-products, cereals, binders, extenders or fillers, these items are creditable without a CN label or Product Formulation Statement. Foods with a Standard of Identity include: Hot Dogs Pork Sausage Bologna Ham and Turkey Ham Vienna Sausage Canadian Bacon Standard of Identity Legal definition of what a food actually is. Standards of identity help consumers identify the product they are purchasing. Example: "Canned Tuna" must legally be tuna and not a different type of fish. -

Food Innovations Gourmet Food Products

2016 Products available through US Foods Culinary Equipment & Supplies®. To place an order, log on to your US Foods Online account, or contact your US Foods sales representative. Please allow up to 5 business days for delivery. What sets a great Chef apart from his or‘‘ her comrades is the ability to be unique. ’’ Food Innovations is a Chef driven, Chef operated company dedicated to assisting culinary creativity by sourcing and supplying the best specialty products in the world. Items include fresh sustainable seafood from around the world, all natural meats, game and sausages, exotic fruits and vegetables, Japanese imports, hand crafted chocolates, artisan cheeses. Food Innovations has the ability to source and procure the most exotic and hard to find products in the world. AAboutbout FooFood InnInnovations u Single Source for Hard to Find Ingredients u Direct from the Boat, Farm or Ranch to Your Door u Imported Specialties from Around the World u Center of the Plate Specialties UÊÊ iÕÊÌià UÊÊ } ÌÞÊ-«iV>à UÊÊ `>ÞÃÊ>`Ê-«iV>Ê ÛiÌà u Ingredients UÊÊ Ài>ÌiÊ ÝÌVÊ>`Ê ÝVÌ}Ê Ã ià UÊÊ >ViÊ>ÛÀà UÊÊ ÃÌ}Õà ÊÞÕÀÊ,iÃÌ>ÕÀ>Ì uÊÊ Àià iÃÌÊ*À`ÕVÌÊ iÛiÀi`ÊÛ>Êi` Ý uÊÊ ÛiÀÞÊ"À`iÀÊ/À>Vi`ÊÌ ÀÕ} ÊÌÊ wÀi`Ê iÛiÀÞ uÊÊ /i>ÊvÊ ivÃ]Ê Õ>ÀÞÊ/À>i`Ê`ÛÃÀÃÊ and Logistical Professionals. Fresh and Origin Specific uÊÊ *À`ÕVÌÃÊvÀÊÀi}ÃÊvÊÌ iÊÜÀ`ÊVÕ`}Ê>Ã>]ÊÕÃÌÀ>>]Ê À>Vi]Ê>Ü>]ÊÌ>ÞÊ>`Ê-«>° uÊÊ 1µÕiÊ"À}Ê-«iVwVÊÃi>v`]Êi>Ì]Ê«ÕÌÀÞ]ÊV iiÃi]Ê«À`ÕViÊ and ingredients sourced under one roofÊLÞÊ`ÊÛ>Ìð uÊÊ iÛiÀi`Ê`ÀiVÌÞÊÌÊÞÕÊvÀÊÌ iÊÃÕÀVi° Freshness Saves You Money uÊÊ -i>v`ÊvÀÊÌ iÊÃÕÀViÊ >ÃÊ}iÀÊà ivÊvi°°°ÊÓxÊ`>ÞÃÊ}iÀ uÊÊ ÜiÀÊ«ÀVi`ÊÜ>Ài ÕÃiÊÀÊvÀâiÊ«À`ÕVÌÊV>ÊÀiÃÕÌÊÊi>ÀÞÊ Ã«>}iÊvÀÊ`à i`Êà ivÊvi°°Ê>ÊVÃÌÞÊ>ÌiÀ>ÌÛit u Unique Ingredients...or Something Special.. -

Aproveitamento De Subprodutos Da Indústria De Carne Suína: Caracterização Físico-Química Do Queijo De Porco

UNIVERSIDADE TECNOLÓGICA FEDERAL DO PARANÁ MESTRADO PROFISSIONAL EM TECNOLOGIA DE ALIMENTOS JAMIL CORREIA DA SILVA JUNIOR APROVEITAMENTO DE SUBPRODUTOS DA INDÚSTRIA DE CARNE SUÍNA: CARACTERIZAÇÃO FÍSICO-QUÍMICA DO QUEIJO DE PORCO DISSERTAÇÃO DE MESTRADO LONDRINA 2015 JAMIL CORREIA DA SILVA JUNIOR APROVEITAMENTO DE SUBPRODUTOS DA INDÚSTRIA DE CARNE SUÍNA: CARACTERIZAÇÃO FÍSICO-QUÍMICA DO QUEIJO DE PORCO Dissertação de mestrado, apresentada ao Curso de Mestrado Profissional em Tecnologia de Alimentos, da Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná – UTFPR, câmpus Londrina, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Tecnologia de Alimentos. Orientadora: Profª Drª Alessandra Machado Lunkes Coorientadora: Profª Drª Mayka Reghiany Pedrão LONDRINA 2015 Ministério da Educação Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná Programa de Pós-Graduação em Tecnologia de Alimentos FOLHA DE APROVAÇÃO APROVEITAMENTO DE SUBPRODUTOS DA INDÚSTRIA DE CARNE SUÍNA: CARACTERIZAÇÃO FÍSICO-QUÍMICA DO QUEIJO DE PORCO por JAMIL CORREIA DA SILVA JUNIOR Esta dissertação foi apresentada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de MESTRE EM TECNOLOGIA DE ALIMENTOS – Área de Concentração: Tecnologia de Alimentos, pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Tecnologia de Alimentos – PPGTAL – da Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná – UTFPR – Câmpus Londrina às 19 h do dia 28 de agosto de 2015. O trabalho foi aprovado pela Banca Examinadora, composta por: ________________________________ _______________________________ Profª. Drª. Alessandra Machado Lunkes Prof. -

Sandwich Meat Guide

Sandwich Meat Guide To place an order, call 410-677-5600 or 1-877-677-5600 Revised 7/22/11 CONTENTS BEEF BURGERS TURKEY & V EGGIE BURGERS FRANKS PAGES 5-6 PAGE 7 PAGES 8-9 CORN DOGS BEEF PHILLY CHICKEN PHILLY PAGE 9 PAGE 10-11 PAGE 11 BARBECUE SLOPPY JOES BEEF BRISKET /C ORNED BEEF PAGE 12 PAGE 12 PAGE 13 DELI MEATS PRE -M ADE SANDWICHES SAUSAGES PAGES 14-15 PAGE 16 PAGE 16 2 Find recipes and serving ideas on sandwichbuildersonline.com™ or call us at 888-737-3832. The right tools for the bread.® 1 Technomic, 2004 3 Oscar Mayer offers your customers the The undisputed top dog. high quality they expect with the flavor and fun to satisfy appetites of all ages. Retain customers, satisfy demand and increase profits by offering the #1 brand of hot dogs and links in America. 1 1. ACNielsen, June 2005 When you’re hungry for barbecue, nothing else will do. 4 BURGERS BEEF 0817999 8/5 LB FIREANG BEEF GRND CHUCK ANGUS CH 81/19 8142366 6/10#AVG CAB BEEF GRND CHUCK FINE 80/20 6294623 40/4 OZ CAB BEEF PATTY CHUCK CKD PUB 6294805 27/6 OZ CAB BEEF PATTY CHUCK CKD PUB 1561364 40/4 OZ SYS CLS BEEF PATTY PUB BRGR PRCKD 2720571 32/5 OZ ADVANCE BEEF PATTY SLSBRY CHAR 6510846 90/2.5OZ ADVANCE BEEF PATTY CHRBRL 2398121 80/2 OZ SYS REL BEEF PATTY GRND CHARBRLD 7097108 15/1 LB FIRERVR BEEF GRND BULK 80/20 FINE 8831218 384/1.25OZ MAID RT BEEF PATTY CHARBRL LTL ANDIES 7236367 40/4 OZ FIRERVR BEEF PATTY GRND 75/25 SCRD 2259828 50/3.2OZ FIRERVR BEEF PATTY GRND 80/20 1120005 60/2.66OZ FIRERVR BEEF PATTY GRND 80/20 2421014 60/2.67OZ FIRERVR BEEF PATTY GRND 80/20 JUICY -

National Cuisine

EXPRESSING OPINION y Well, the first thing that comes to my mind is … y As you know … y No doubt … y Actually … y As a matter of fact … y By the way … y To be honest … y Perhaps … y I mean … y It can’t hurt to try. y Firstly / Secondly / Finally … y Exactly! y Sounds impressive! y – Thank you. – It was a pleasure! AT THE CAFЙ Customer: y What’s … exactly? Is this served with … (salad)? Is it … (hot / spicy)? y Does this have any … (seafood) in it? Are there any … (nuts) in the dish? What do you recommend? y I’ll have … / I’d like (to order) … / Can I have … Well, everything looks so appetising. What’s … exactly? / What does … include? y Can I have … (but without pepper / nuts / … ), please? y What have you got (for dessert)? y Thank you, it’s delicious / mouth-watering / extremely tasty / … ! y Can I have the bill, please? Waiter: y Are you ready to order? y I’d recommend … . y It’s … (soup) made with … (lamb pieces, noodles, mushrooms and beans). y Would you like the steak rare, medium-rare or well- done? y Anything to drink? y Sparkling or still? y Would you care for dessert? y Do you like your food? y How’s the meal? y Sure, are you going to pay in cash or by credit card? y Here you are. ASKING FOR AND GIVING ADVICE y What should I do? y What's the best way to deal with this problem? y Can you give me any advice? y Do I need to … ? y Do you think I should … ? y I don’t think you should … y If I were you, I would … y Why not … ? y Why don’t you y Try to … y If you really want … , make sure … y I totally understand where you’re coming from … y You should definitely / also … y You could always … LET’S CELEBRATE! y What are you talking about? y It’s all over the news. -

WINTERSVILLE, OHIO Headquarters

__ WINTERSNILL CT IZEN VOL. 1, NO. 39 THURSDAY, AUGUST 29, 1963-TEN PAGES $5.00 per year 10< per copy SO, IT'S ..... .. .. .. .. BACK TO By EVE SEITER Suddenly it's September! So, 5-TIME AT THE MIRROR.. it's back to school again. Delv- No member of this institution ing into some old books this shall tarry before the mirror writer discovered a copy of en- more than three consecutive trance requirements for South minutes. Hadley Seminary, which later 6 - READING .. No member became known at Mt. Holyoke of this school shall devote more College. 'Here are a few of the than one hour each week to rules: miscellaneous reading. The AT- "1- ADMISSION . No young LANTIC MONTHLY, Shake- lady shall become a member of speare, Scott's novels, ROBIN- this school who cannot kindle a SON CRUSOE, and immoral fire, wash potatoes, and repeat works are strictly forbidden. the multiplication table. T H E BOSTON RECORDER, 2 - OUTFIT .. No cosmetics, MISSIONARY HERALD, and perfumery, or fancy soap will Washiington's Farewell. Address be allowed on the premises. are earnestly recommended for 3-EXERCISE .. Every mem- light reading." ber of this school shall walk at Home Ec', Math, the natural least a mile every- day. look, physical fitness, suitable 4 - COMPANY. No member company, modesty, a sense of of this school is expected to discrimination -- a rare yard- have any male acquaintances stick of behavior! We offer it unless they are retired mission- to those who find it's back to The new shelters which are mission was given by Village aries or agents of some benevo- school for them again! being installed at the bus stops officials.