Istanbul, 8-10 October 1992 CDL-STD(1992)003 Or Engl/Fr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Band and Panel Listings Inside!

THE STROKES FOUR TET NEW MUSIC REPORT ESSENTIAL October 15, 2001 www.cmj.com DILATED PEOPLES LE TIGRE CMJ MUSIC MARATHON ’01 OFFICIALGUIDE FEATURING PERFORMANCES BY: Bis•Clem Snide•Clinic•Firewater•Girls Against Boys•Jonathan Richman•Karl Denson•Karsh Kale•L.A. Symphony•Laura Cantrell•Mink Lungs• Murder City Devils•Peaches•Rustic Overtones•X-ecutioners and hundreds more! GUEST SPEAKER: Billy Martin (Medeski Martin And Wood) COMPLETE D PANEL PANELISTS INCLUDE: BAND AN Lee Ranaldo/Sonic Youth•Gigi•DJ EvilDee/Beatminerz• GS INSIDE! DJ Zeph•Rebecca Rankin/VH-1•Scott Hardkiss/God Within LISTIN ININ STORESSTORES TUESDAY,TUESDAY, SEPTEMBERSEPTEMBER 4.4. SYSTEM OF A DOWN AND SLIPKNOT CO-HEADLINING “THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE TOUR” BEGINNING SEPTEMBER 14, 2001 SEE WEBSITE FOR DETAILS CONTACT: STEVE THEO COLUMBIA RECORDS 212-833-7329 [email protected] PRODUCED BY RICK RUBIN AND DARON MALAKIAN CO-PRODUCED BY SERJ TANKIAN MANAGEMENT: VELVET HAMMER MANAGEMENT, DAVID BENVENISTE "COLUMBIA" AND W REG. U.S. PAT. & TM. OFF. MARCA REGISTRADA./Ꭿ 2001 SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INC./ Ꭿ 2001 THE AMERICAN RECORDING COMPANY, LLC. WWW.SYSTEMOFADOWN.COM 10/15/2001 Issue 735 • Vol 69 • No 5 CMJ MUSIC MARATHON 2001 39 Festival Guide Thousands of music professionals, artists and fans converge on New York City every year for CMJ Music Marathon to celebrate today's music and chart its future. In addition to keynote speaker Billy Martin and an exhibition area with a live performance stage, the event features dozens of panels covering topics affecting all corners of the music industry. Here’s our complete guide to all the convention’s featured events, including College Day, listings of panels by 24 topic, day and nighttime performances, guest speakers, exhibitors, Filmfest screenings, hotel and subway maps, venue listings, band descriptions — everything you need to make the most of your time in the Big Apple. -

Istanbulstudy Tour Report

Istanbul Study Tour Report February 1 – February 9, 2014 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Challenges .................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Istanbul as a Destination .................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 Sunday activity ........................................................................................................................... 7 2.1.1 Concept of the task ............................................................................................................. 7 2.2 The results .................................................................................................................................. 7 2.2.1 Group Results ...................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Further observations .................................................................................................................. 9 3. Destination Management .............................................................................................................. 11 3.1 Lonely Planet ............................................................................................................................ 12 3.2 Istanbul Convention and Visitor Bureau -

Gigs of My Steaming-Hot Member of Loving His Music, Mention in Your Letter

CATFISH & THE BOTTLEMEN Van McCann: “i’ve written 14 MARCH14 2015 20 new songs” “i’m just about BJORK BACK FROM clinging on to THE BRINK the wreckage” ENTER SHIKARI “ukiP are tAKING Pete US BACKWARDs” LAURA Doherty MARLING THE VERDICT ON HER NEW ALBUM OUT OF REHAB, INTO THE FUTURE ►THE ONLY INTERVIEW CLIVE BARKER CLIVE + Palma Violets Jungle Florence + The Machine Joe Strummer The Jesus And Mary Chain “It takes a man with real heart make to beauty out of the stuff that makes us weep” BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME15011142.pgs 09.03.2015 11:27 EmagineTablet Page HAMILTON POOL Home to spring-fed pools and lush green spaces, the Live Music Capital of the World® can give your next performance a truly spectacular setting. Book now at ba.com or through the British Airways app. The British Airways app is free to download for iPhone, Android and Windows phones. Live. Music. AustinTexas.org BLACK YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN 93NME15010146.pgs 27.02.2015 14:37 BAND LIST NEW MUSICAL EXPRESS | 14 MARCH 2015 Action Bronson 6 Kid Kapichi 25 Alabama Shakes 13 Laura Marling 42 The Amorphous Left & Right 23 REGULARS Androgynous 43 The Libertines 12 FEATURES Antony And The Lieutenant 44 Johnsons 12 Lightning Bolt 44 4 SOUNDING OFF Arcade Fire 13 Loaded 24 Bad Guys 23 Lonelady 45 6 ON REPEAT 26 Peter Doherty Bully 23 M83 6 Barli 23 The Maccabees 52 19 ANATOMY From his Thai rehab centre, Bilo talks Baxter Dury 15 Maid Of Ace 24 to Libs biographer Anthony Thornton Beach Baby 23 Major Lazer 6 OF AN ALBUM about Amy Winehouse, sobriety and Björk 36 Modest Mouse 45 Elastica -

CIRCUS October 1971

Iff FREE! [(HARRISON POSTER I'y^r ■ ’ ' ■ NEW moodyA *s*in BLUES JI B-ME w !tN th IP PINK J ■ J FLOY a r The Bloody Blues new album Every Good Boy Deserves Favour I As in life, so in music As in music, so in life K ggr- -■ ls0pl& £1 THS 5 I- fc\. MIMUUO Of -WWMCCMDf &e iP>: Soft Machine Vol. 6 No. 1 emeus October 1971 ARTICLES THE STORY BEHIND THE BENGLA DESH CONCERT 4 What brought George, Ringo, Leon, Dylan and Clapton to the Garden? THE INTERSTELLAR THUNDER OF PINK FLOYD 20 The electronic birdmen put their old eggs in a new platter. THE SWIRLING SOUND OF SOFT MACHINE 24 Ignored when they toured with Hendrix, standing-ovationed today. WOODSTOCK: A TIN PAN ALLEY RIP OFF 28 Abbie Hoffman on Janis. Jagger and Greed. RELIGIOUS REVIVAL IN THE ROCK CULTURE 30 Peter Townshend, George Harrison and the Cat are among God’s helpers. PETE SEEGER’S RAINBOW RACE 31 The folk patriarch points a political finger at you and me. THE ELUSIVE MOODY BLUES 32 With five gold albums, how have they avoided fame? AN INTERVIEW WITH JOE McDONALD 36 Poetry and pointed shoes? Guess there’s a new Country Joe. AN INTIMATE LOOK AT ROD THE MOD 54 Making an album on a bottle of brandy. DEEP PURPLE: OVERCOMING THE IMAGE CRISIS 60 Will Fireball burn away the confusion? FEATURES LETTERS 12 Wrecking a church for Iggy. RECORD REVIEWS 16 Blood, Sweat & Tears, Stephen Stills, Beach Boys and more. POEMS 23 Morrison: laying the lizard king to rest. -

The Final Cut

DECEMBER 31, 2001 VOLUME 16 #2 The Final Cut Plotting World Domination from Altoona Otherwise…CD/Tape/Culture analysis and commentary with D’Scribe, D’Drummer, Da Boy, D’Sebastiano’s Doorman, Da Common Man, D’ Big Man, Al, D’Pebble, Da Beer God and other assorted riff raff… D'RATING SYSTEM: 9.1-10.0 Excellent - BUY OR DIE! 4.1-5.0 Incompetent - badly flawed 8.1-9.0 Very good - worth checking out 3.1-4.0 Bad - mostly worthless 7.1-8.0 Good but nothing special 2.1-3.0 Terrible - worthless 6.1-7.0 Competent but flawed 1.1-2.0 Horrible - beyond worthless 5.1-6.0 Barely competent 0.1-1.0 Bottom of the cesspool abomination! SEPTEMBER 11, 2001. At this point in time, there isn’t much I can possibly say about that date that hasn’t already been said time and time again…It looked like a Hollywood disaster movie, but it was real. And while the air crash in Somerset County didn’t get quite the ink or attention of the New York or D.C. terrorist attacks, it brought terrorism home right to our backyard. Nobody is immune or totally safe anymore. Thus far, I’m giving a huge thumbs up to President Bush and our government in their actions in the wake of the attacks. I don’t like war any more than anybody else, but when somebody violates thousands of lives and does so on American soil, something needs to be done. And I approve of the approach thus far – this is a huge criminal investigation. -

Faith No More Download 2009L

Faith No More Download 2009l 1 / 4 Faith No More Download 2009l 2 / 4 3 / 4 Jump to 2009 - The 2009 Download Festival took place on 12–14 June at ... The headliners were Faith No More (Friday), Slipknot (Saturday) and Def .... Second concert after 11 years @Download festival 12JUN 2009. ... 50+ videos Play all Mix - Faith No More .... The good people at plucky internet start-up YouTube are now allowing long-length video clips and a top .... The headline should say everything, right? This past weekend, at Download Festival '09, Faith No More reunited. Yes, the same band that .... But Faith No More's Donington Park gig will be their only UK appearance in 2009, organisers said, putting an end to rumours of gigs at .... Entdecken Sie Sol Invictus von Faith No More bei Amazon Music. Werbefrei streamen oder als CD und MP3 kaufen bei Amazon.de. ... Format: MP3-DownloadVerifizierter Kauf. Meiner Meinung ... Faith No More: Live in Germany 2009 (Live).. Here's the set list: Reunited The Real Thing From Out of Nowhere Land of Sunshine Caffeine Evidence Poker Face / Chinese Arithmetic. Get the Faith No More Setlist of the concert at Donington Park, Castle Donington, England on June 12, 2009 from the The Second Coming Tour .... Im Februar bestätigten FAITH NO MORE, dass sie zur Festival-Saison 2009 eine Re-Union planen, um auf dem Download-Festival im Londoner Donington Park .... Faith No More - Download 2009 Set. By itsronald. Faith No More Download 2009 Set. 42 songs. Play on Spotify. 1. ReunitedPeaches & Herb • 2 Hot! 5:450: .... Regardez FAITH NO MORE - Easy (Download Festival 2009) - the kid sur Dailymotion. -

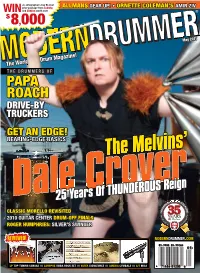

DALE CROVER the Melvins’ Thunder King Has Been Summoning the Wrath of the Heavens for More Than Twenty-Five Years

ANAUTOGRAPHED*OEY+RAMER PRIZEPACKAGEFROM,UDWIG !,,-!.3'%!250s/2.%44%#/,%-!.3!-)2:)6 7). AND:ILDJIANWORTHOVER -AY 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 4(%$25--%23/& 0!0! 2/!#( $2)6% "9 425#+%23 '%4!.%$'% "%!2).' %$'%"!3)#3 5IF.FMWJOT :FBST0G5)6/%&30643FJHO #,!33)#-/2%,,/2%6)3)4%$ '5)4!2#%.4%2$25- /&&&).!,3 2/'%2(5-0(2)%33),6%2337).'%2 3&7*&8&% -/$%2.$25--%2#/- ,04/0 45.).'#/.'!3#!./0539!)"!2/#+3%46!4%23)'.!452%3!-%$)!#9-"!,3!4-)#3 Volume 35, Number 5 • Cover photo by Alex Solca CONTENTS 44 29 ROGER HUMPHRIES Alex Solca In 1967 he left a plum gig with Horace Silver to follow his heart—back home. More than forty years later, his reputation as one of the most stylish players and most effective teachers around has only grown. 38 AMIR ZIV Combining jazz, electronic, free, and Brazilian styles, the New York avant-everything drummer proves there are always new worlds to conquer—in his playing, and in his clinics, classes, and drum-centric getaways. Only the fearless need apply. 44 DALE CROVER The Melvins’ thunder king has been summoning the wrath of the heavens for more than twenty-five years. His reign continues uncontested—yet he’s invited another storm- bringer to rattle the earth beside him. MD speaks with Crover and his percussive partner, Coady Willis. 80 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT...? TULSA TIME Chuck Blackwell, Jimmy Karstein, David Teegarden, and the unique scene that fueled classic rock 29 14 UPDATE Ratt’s BOBBY BLOTZER Gang Of Four’s MARK HEANEY Mose Allison/Lee Konitz’s RON FREE 16 GIMME 10! Papa Roach’s TONY PALERMO Fred Michael 38 66 PORTRAITS Drive-By Truckers’ BRAD MORGAN 88 FROM THE PAST Paul La Raia Classical Roots, Part 1 EDGARD VARESE MD DIGITAL SUBSCRIBERS! When you see this icon, click on a shaded box on the page to open the audio player. -

Pictures of Lily', ‘Substitute’ and ‘The Kids Are Alright’

1984 23 October Hampstead Moonlight (anti-heroin benefit) Date: 23rd October 1984 Location: Hampstead Moonlight, London, England Supporting: Mercenary Skank, High Noon, and a secret special guest, who turned out to be Pete Townshend. Media reviews: Memories of fans: I am not the biggest fan of The Stone Roses but it turns out I was at their first ever gig. So, a mate of mine told me that I should share my story and I was pointed in your direction. So here we go. You can have this. It was the first time I saw Pete Townshend live and I was (and still am) an avid fan of The Who, but before I seen him I waited anxiously and watched the support group. Recently I found out that they were a little known group called The Stone Roses. They turned out to be the biggest band of their generation. I remember very little of their set. But I can remember them like The Cure. I remember how the singer was in charge of the stage. That was a week after I turned 17 and not only did I manage to see my hero, Pete Townshend for the first time but I managed to see, possibly the inventors of Brit-pop and saviours of British guitar rock, The Stone Roses. I saw the Stone Roses at Leicester many years later and there was a difference but more memory with the latter. I was speaking to a friend in Brussels who did have photos of The Stone Roses live at the Moonlight in 1984 but sold them around 1995 to a collector in London for £700. -

Daniel Davison

WIN A PREMIER/SABIAN PACKAGE WORTH $6,450 THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE APPS YOU NEED 9 TO KNOW TERENCE BLANCHARD’S OSCAR SEATON PORTRAIT OF A COMPLETE MUSICIAN ILAN RUBIN OF NIN/ANGELS & AIRWAVES/THE NEW REGIME OCTOBER 2015 BEN THATCHER: ROYAL BLOOD BLAKE RICHARDSON: BETWEEN THE BURIED AND ME JOE VITALE: JOE WALSH, CSN…MERYL STREEP? 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 June 2014 Modern Drummer 1 SHAPE Y O U R SOUND Bose® F1 Model 812 Flexible Array Loudspeaker 1 speaker. 4 coverage patterns. STRAIGHT J REVERSE J C Introducing the first portable loudspeaker that lets you easily control the vertical coverage – so wherever you play, more music reaches more people directly. The Bose F1 Model 812 Flexible Array Loudspeaker’s revolutionary flexible array lets you manually select from four coverage patterns, allowing you to adapt your PA to the room. Plus, the loudspeaker and subwoofer provide a combined 2,000 watts of power, giving you the output and impact for almost any application. Your audience won’t believe their ears. Bose.com/F1 ©2015 Bose Corporation. CC017045 2 Modern Drummer June 2014 BOS80570_ModernDrummer.indd 1 23/06/2015 12:48 PM PROUD PROUD DW Proud Ad - Josh F - FULL (MD).indd 1 7/16/15 11:30 AM SAYRE BERMAN PHOTOGRAPHY “From a young age I CONTENTS was taught to treat being a musician as a Volume 39 • Number 10 real skill. At twenty, 38 On the Cover when I joined Nine Inch Nails, I thought, ‘This is Ilan Rubin the kind of organization by Ken Micallef I want to be a part of.’” Trent Reznor isn’t the only rock star who’s seen the value of Ilan Rubin’s mature approach to art and commerce; the members of Paramore and Angels & Airwaves have tapped his considerable skills as well. -

The Second Coming of Paisley: Militant Fundamentalism and Ulster Politics

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 The second coming of Paisley: militant fundamentalism and Ulster politics in a transatlantic context Richard Lawrence Jordan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Jordan, Richard Lawrence, "The es cond coming of Paisley: militant fundamentalism and Ulster politics in a transatlantic context" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 876. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/876 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SECOND COMING OF PAISLEY: MILITANT FUNDAMENTALISM AND ULSTER POLITICS IN A TRANSATLANTIC CONTEXT A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Facility of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Richard L. Jordan B.A. University of Southern Mississippi, 1998 M.A. University of Southern Mississippi, 2002 December 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS . iv ABSTRACT. v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 The Importance of Militant Fundamentalism to Ian Paisley . 4 The Historiography of “The Troubles” . 12 2. THE TRANSATLANTIC BACKGROUND TO FUNDAMENTALISM . 17 Reformation and Puritanism . 20 The Plantation of Presbyterianism into the American Colonies . 23 The Legacy of The First Ulster Awakening . 26 Colonial Revivalism . 27 Nineteenth-Century Revivalism. -

Melvins Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit: „The Melvins. Geschichte, Analyse und Neubewertung eines (außer-) musikalischen Phänomens.“ Verfasser Clemens Marschall angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: 316 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Musikwissenschaft Betreuer: Ao.Univ.-Prof.Dr. Manfred Angerer Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort 1. Einführung 4 2. Pre-Melvins 8 3. 1982-1984 (Montesano): Buzz Osborne, Mike Dillard, Matt Lukin 14 4. 1984-1988 (Aberdeen): Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover, Matt Lukin 17 5. 1988-1991 (San Francisco): Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover, Lori Black 34 6. 1991-1992 (San Francisco): Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover, Joe Preston 42 7. 1992-1993 (San Francisco): Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover, Lori Black 47 8. 1993-1998 (Los Angeles, San Francisco, London): Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover, Mark „D” Deutrom 56 9. 1998-2005 (Los Angeles, San Francisco): Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover, Kevin Rutmanis 81 10. 2005 (Los Angeles): Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover, David Scott Stone 110 11. 2005 (Los Angeles): Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover, Trevor Dunn 111 12. seit 2006 (Los Angeles): Buzz Osborne, Dale Crover, Coady Willis, Jared Warren 112 13. Rück- und Ausblick 116 14. Zusammenfassung 123 15. Literaturverzeichnis 124 16. Abbildungsverzeichnis 129 17. Anhang 130 18. Lebenslauf 138 1 Vorbemerkung zur Schreibweise In dieser Arbeit wurde aus Gründen des Leseflusses auf eine durchgehnd geschlechtsneutrale Formulierung verzichtet. Der Autor ist sich allerdings der diesbezüglichen Problematik bewusst und hat versucht, eine weitgehend neutrale, nicht diskriminierende Sprache einzusetzen. Bei direkt zitierten Interviewpassagen habe ich die Originalschreibweise übernommen.