Shining Light on the Federal Regulatory Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E910 HON

E910 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks July 12, 2019 CELEBRATING THE 30TH ANNIVER- tary activities of the Department of Defense The direct economic cost of the war in Af- SARY OF THE AMERICAN ASSO- and for military construction, to prescribe ghanistan exceeds $1.07 trillion, including CIATION OF LAW LIBRARIES military personnel strengths for such fiscal $773 billion in Overseas Contingency Oper- year, and for other purposes: ations funds, an increase of $243 billion to the HON. MIKE QUIGLEY Ms. JACKSON LEE. Madam Chair, I rise to Department of Defense base budget, and an speak in support of Amendment No. 423 to increase of $54.2 billion to the Veterans Ad- OF ILLINOIS H.R. 2500, the National Defense Authorization IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ministration budget to address the human Act for FY2020, offered by the gentleman from costs of the military involvement in Afghani- Friday, July 12, 2019 California, Congressman RO KHANNA. stan. Mr. QUIGLEY. Madam Speaker, I rise today The Khanna Amendment is simple and We should not repeat the mistakes of the in celebration of the 30th anniversary of the straightforward in its prohibition against unau- past and my position on this issue is directly American Association of Law Libraries’ legisla- thorized military force in or against Iran. aligned with the will of the American people. Earlier this year, the Trump Administration tive advocacy program. The American Asso- I commend my colleague, Congressman sent an aircraft carrier and a nuclear-powered ciation of Law Libraries (AALL), representing KHANNA for offering this important amendment submarine to the region in a show of force. -

117Th Illinois Congressional Delegation

ILLINOIS CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION 117th Congress Two Senators represent each state in the U.S. Senate and are elected to serve six-year terms. U.S. Senator Dick Durbin (D) of Springfield was elected to represent Illinois for a fifth term in 2020. Tammy Duckworth of Hoffman Estates (D) was elected to the U.S. Senate in 2016. (See pages 16-19 for U.S. Senator photos and biographies.) In the November 2020 general election, Illinois voters elected 18 candidates to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives for two-year terms. Thirteen Democratic and five Republican U.S. Representatives were elected to serve in the 117th Congress. The November 2020 general election was historical, with the most women ever elect- ed to serve in Congress. Democrat Marie Newman and Republican Mary Miller — repre- senting districts that were previously held by men — added to the increase of female Representatives. Newman definitively won the general election to represent the 13th District after defeating 16-year incumbent U.S. Rep. Dan Lipinksi (D) in the March pri- mary. Miller won the 15th District seat that was previously held by U.S. Rep. John Shimkus (R), who served 12 terms in Congress and opted not to run for reelection. Since 1818, Illinois has had a total of 20 female U.S. Representatives. In 2021, seven are currently rep- resenting our state — a record-breaking total. The 117th Congress serves from Jan. 3, 2021, to Jan. 3, 2023. A view of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. 36 | 2021-2022 ILLINOIS BLUE BOOK 1st Congressional District BOBBY L. -

Calling on the Census Bureau

September 3, 2020 Dr. Steven Dillingham Director United States Census Bureau 4600 Silver Hill Road Washington, DC 20233 Dear Dr. Dillingham: This letter is to inquire about the U.S. Census Bureau’s plans for accurately counting our country’s population in the 2020 Census. In California, nearly 15 percent of our residents remain uncounted, many in historically undercounted communities at risk of losing federal funding and resources. In light of the challenges created by COVID-19, the fires burning across California, and the recent decision to end counting operations early, we ask that you provide additional detail about how a complete count will be achieved. It is our understanding that with the shortened counting timeline, Census Bureau workers will need to visit 8 million more homes nationwide than in 2010, in just seven weeks instead of ten weeks. Data accuracy and review procedures for processing apportionment counts have also been reduced from six months to three months. Additional obstacles caused by COVID-19 include a higher number of people experiencing homelessness—an historically undercounted population—as well as difficulties with hiring and retention of census workers. Given these significant barriers to a fair and accurate census, we would appreciate answers to the following questions. With in-person counting operations cut short, the Census Bureau will likely need to utilize administrative records and statistical techniques to complete the enumeration. Do you now anticipate any changes in the number of households that will -

2017 Political Contributions (January 1 – June 30)

2017 Political Contributions (January 1 – June 30) Amgen is committed to serving patients by transforming the promise of science and biotechnology into therapies that have the power to restore health or even save lives. Amgen recognizes the importance of sound public policy in achieving this goal, and, accordingly, participates in the political process and supports those candidates, committees, and other organizations who work to advance healthcare innovation and improve patient access. Amgen participates in the political process by making direct corporate contributions as well as contributions through its employee-funded Political Action Committee (“Amgen PAC”). In some states, corporate contributions to candidates for state or local elected offices are permissible, while in other states and at the federal level, political contributions are only made through the Amgen PAC. Under certain circumstances, Amgen may lawfully contribute to other political committees and political organizations, including political party committees, industry PACs, leadership PACs, and Section 527 organizations. Amgen also participates in ballot initiatives and referenda at the state and local level. Amgen is committed to complying with all applicable laws, rules, and regulations that govern such contributions. The list below contains information about political contributions for the first half of 2017 by Amgen and the Amgen PAC. It includes contributions to candidate committees, political party committees, industry PACs, leadership PACs, Section 527 organizations, and state and local ballot initiatives and referenda. These contributions are categorized by state, political party (if applicable), political office (where applicable), recipient, contributor (Amgen Inc. or Amgen PAC) and amount. Office Candidate State Party Office Committee/PAC Name Candidate Name Corp. -

Union Calendar No. 881

1 Union Calendar No. 881 115TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 115–1114 ACTIVITIES OF THE HOUSE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS JANUARY 2, 2019 (Pursuant to House Rule XI, 1(d)(1)) Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdys.gov http://oversight.house.gov/ JANUARY 2, 2016.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 33–945 WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Sep 11 2014 05:03 Jan 08, 2019 Jkt 033945 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR1114.XXX HR1114 SSpencer on DSKBBXCHB2PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM TREY GOWDY, South Carolina, Chairman JOHN DUNCAN, Tennessee ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland DARRELL ISSA, California CAROLYN MALONEY, New York JIM JORDAN, Ohio ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of MARK SANFORD, South Carolina Columbia JUSTIN AMASH, Michigan WILLIAM LACY CLAY, Missouri PAUL GOSAR, Arizona STEPHEN LYNCH, Massachusetts SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee JIM COOPER, Tennessee VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky ROBIN KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDA LAWRENCE, Michigan DENNIS ROSS, Florida BONNIE WATSON COLEMAN, New Jersey MARK WALKER, North Carolina RAJA KRISHNAMOORTHI, Illinois ROD BLUM, Iowa JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland JODY B. HICE, Georgia JIMMY GOMEZ, California STEVE RUSSELL, Oklahoma PETER WELCH, Vermont GLENN GROTHMAN, Wisconsin MATT CARTWRIGHT, Pennsylvania -

JOIN the Congressional Dietary Supplement Caucus

JOIN the Congressional Dietary Supplement Caucus The 116th Congressional Dietary Supplement Caucus (DSC) is a bipartisan forum for the exchange of ideas and information on dietary supplements in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. Educational briefings are held throughout the year, with nationally recognized authors, speakers and authorities on nutrition, health and wellness brought in to expound on health models and provide tips and insights for better health and wellness, including the use of dietary supplements. With more than 170 million Americans taking dietary supplements annually, these briefings are designed to educate and provide more information to members of Congress and their staff about legislative and regulatory issues associated with dietary supplements. Dietary Supplement Caucus Members U.S. Senate: Rep. Brett Guthrie (KY-02) Sen. Marsha Blackburn, Tennessee Rep. Andy Harris (MD-01) Sen. John Boozman, Arkansas Rep. Bill Huizenga (MI-02) Sen. Tom Cotton, Arkansas Rep. Derek Kilmer (WA-06) Sen. Tammy Duckworth, Illinois Rep. Ron Kind (WI-03) Sen. Martin Heinrich, New Mexico Rep. Adam Kinzinger (IL-16) Sen. Mike Lee, Utah Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi (IL-08) Sen. Tim Scott, South Carolina Rep. Ann McLane Kuster (NH-02) Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, Arizona Rep. Ted Lieu (CA-33) Rep. Ben Ray Luján (NM-03) U.S. House of Representatives: Rep. John Moolenaar (MI-04) Rep. Mark Amodei (NV-02) Rep. Alex Mooney (WV-02) Rep. Jack Bergman (MI-01) Rep. Ralph Norman (SC-05) Rep. Rob Bishop (UT-01) Rep. Frank Pallone (NJ-06) Rep. Anthony Brindisi (NY-22) Rep. Mike Rogers (AL-03) Rep. Julia Brownley (CA-26) Rep. -

Leadership PAC $6000 Byrne for Congress Rep. Bradley

L3Harris Technologies, Inc. PAC 2020 Cycle Contributions Name Candidate Office Total ALABAMA American Security PAC Rep. Mike Rogers (R) Leadership PAC $6,000 Byrne for Congress Rep. Bradley Byrne (R) Congressional District 1 $2,000 Defend America PAC Sen. Richard Shelby (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 Doug Jones for Senate Committee Sen. Doug Jones (D) United States Senate $5,000 Martha Roby for Congress Rep. Martha Roby (R) Congressional District 2 $3,000 Mike Rogers for Congress Rep. Mike Rogers (R) Congressional District 3 $11,000 Robert Aderholt for Congress Rep. Robert Aderholt (R) Congressional District 4 $3,500 Terri Sewell for Congress Rep. Terri Sewell (D) Congressional District 7 $10,000 Together Everyone Realizes Real Impact Rep. Terri Sewell (D) Leadership PAC $5,000 (TERRI) PAC ALASKA Alaskans For Dan Sullivan Sen. Dan Sullivan (R) United States Senate $5,000 Lisa Murkowski For US Senate Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R) United States Senate $5,000 ARIZONA David Schweikert for Congress Rep. David Schweikert (R) Congressional District 6 $2,500 Gallego for Arizona Rep. Ruben Gallego (D) Congressional District 7 $3,000 Kirkpatrick for Congress Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Congressional District 2 $7,000 McSally for Senate, Inc Sen. Martha McSally (R) United States Senate $10,000 Sinema for Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D) United States Senate $5,000 Stanton for Congress Rep. Greg Stanton (D) Congressional District 9 $8,000 Thunderbolt PAC Sen. Martha McSally (R) Leadership PAC $5,000 ARKANSAS Crawford for Congress Rep. Rick Crawford (R) Congressional District 1 $2,500 Womack for Congress Committee Rep. Steve Womack (R) Congressional District 3 $3,500 CALIFORNIA United for a Strong America Rep. -

Illinois Congressional Delegation Bios

Illinois Congressional Delegation Bios Senator Richard Durbin (D-IL) Senator Dick Durbin, a Democrat from Springfield, is the 47th U.S. Senator from the State of Illinois, the state’s senior senator, and the convener of Illinois’ bipartisan congressional delegation. Durbin also serves as the Assistant Democratic Leader, the second highest ranking position among the Senate Democrats. Also known as the Minority Whip, Senator Durbin has been elected to this leadership post by his Democratic colleagues every two years since 2005. Elected to the U.S. Senate on November 5, 1996, and re-elected in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Durbin fills the seat left vacant by the retirement of his long-time friend and mentor, U.S. Senator Paul Simon. Durbin sits on the Senate Judiciary, Appropriations, and Rules Committees. He is the Ranking Member of the Judiciary Committee's Subcommittee on the Constitution and the Appropriations Committee's Defense Subcommittee. Senator Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) U.S. Senator Tammy Duckworth is an Iraq War Veteran, Purple Heart recipient and former Assistant Secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs. She was among the first Army women to fly combat missions during Operation Iraqi Freedom. Duckworth served in the Reserve Forces for 23 years before retiring from military service in 2014 at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. She was elected to the U.S. Senate in 2016 after representing Illinois’s Eighth Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives for two terms. In 2004, Duckworth was deployed to Iraq as a Black Hawk helicopter pilot for the Illinois Army National Guard. -

2019 Political Disbursements Federal Candidates Disbursement Ratio

2019 Political Disbursements Federal Candidates Disbursement Ratio Name Amount Democrat Alabama Sen. Doug Jones (D) $2,500 41% California Rep. Amerish Bera (D) $2,000 59% Rep. Devin Nunes (R) $2,000 Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D) $1,000 Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R) $5,000 Republican Rep. Linda Sanchez (D) $2,000 Rep. Mark Takano (D) $1,000 Rep. Raul Ruiz (D) $2,500 Name Amount Rep. Scott Peters (D) $1,000 Sen. Joyce Krawsiec (R) $1,000 Rep. Ted Lieu (D) $500 Rep. Graig Meyer (D) $500 Delaware Sen. Jim Perry (D) $500 Sen. Christopher Coons (D) $1,000 Rep. Larry Potts (R) $500 Rep. Robert Reives (D) $500 Florida Sen. Gladys Robinson (D) $500 Rep. Greg Steube (R) $1,000 Rep. Wayne Sasser (R) $500 Rep. Stephanie Murphy (D) $2,000 Sen. Mike Woodard (D) $500 Georgia Rep. Mark Meadows (R) $1,000 Rep. Douglas Collins (R) $2,500 Rep. Richard Hudson (R) $5,000 Sen. Thom Tillis (R) $4,000 Hawaii Sen. Mazie Hirono (D) $500 North Dakota Rep. Kelly Armstrong (R) $500 Illinois Rep. Brad Schneider (D) $4,000 Nebraska Rep. Cheri Bustos (D) $2,500 Rep. Adrian Smith (R) $2,500 Rep. Darin LaHood (R) $2,500 Nevada Rep. Mike Bost (R) $2,000 Sen. Jacky Rosen (D) $1,000 Rep. Mike Quigley (D) $1,000 Rep. Robin Kelly (D) $1,000 New Hampshire Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R) $1,000 Rep. Ann McClane Kuster (D) $2,000 Rep. S. Raja Krishnamoorthi (D) $1,000 New York Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D) $1,000 Rep. Elise Stefanik (R) $2,000 Sen. -

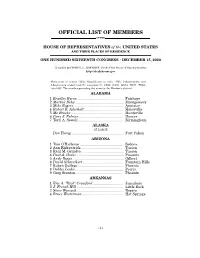

Official List of Members

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS • DECEMBER 15, 2020 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (233); Republicans in italic (195); Independents and Libertarians underlined (2); vacancies (5) CA08, CA50, GA14, NC11, TX04; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Bradley Byrne .............................................. Fairhope 2 Martha Roby ................................................ Montgomery 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................ -

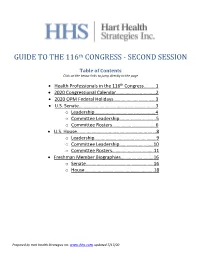

GUIDE to the 116Th CONGRESS

th GUIDE TO THE 116 CONGRESS - SECOND SESSION Table of Contents Click on the below links to jump directly to the page • Health Professionals in the 116th Congress……….1 • 2020 Congressional Calendar.……………………..……2 • 2020 OPM Federal Holidays………………………..……3 • U.S. Senate.……….…….…….…………………………..…...3 o Leadership…...……..…………………….………..4 o Committee Leadership….…..……….………..5 o Committee Rosters……….………………..……6 • U.S. House..……….…….…….…………………………...…...8 o Leadership…...……………………….……………..9 o Committee Leadership……………..….…….10 o Committee Rosters…………..…..……..…….11 • Freshman Member Biographies……….…………..…16 o Senate………………………………..…………..….16 o House……………………………..………..………..18 Prepared by Hart Health Strategies Inc. www.hhs.com, updated 7/17/20 Health Professionals Serving in the 116th Congress The number of healthcare professionals serving in Congress increased for the 116th Congress. Below is a list of Members of Congress and their area of health care. Member of Congress Profession UNITED STATES SENATE Sen. John Barrasso, MD (R-WY) Orthopaedic Surgeon Sen. John Boozman, OD (R-AR) Optometrist Sen. Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA) Gastroenterologist/Heptalogist Sen. Rand Paul, MD (R-KY) Ophthalmologist HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Rep. Ralph Abraham, MD (R-LA-05)† Family Physician/Veterinarian Rep. Brian Babin, DDS (R-TX-36) Dentist Rep. Karen Bass, PA, MSW (D-CA-37) Nurse/Physician Assistant Rep. Ami Bera, MD (D-CA-07) Internal Medicine Physician Rep. Larry Bucshon, MD (R-IN-08) Cardiothoracic Surgeon Rep. Michael Burgess, MD (R-TX-26) Obstetrician Rep. Buddy Carter, BSPharm (R-GA-01) Pharmacist Rep. Scott DesJarlais, MD (R-TN-04) General Medicine Rep. Neal Dunn, MD (R-FL-02) Urologist Rep. Drew Ferguson, IV, DMD, PC (R-GA-03) Dentist Rep. Paul Gosar, DDS (R-AZ-04) Dentist Rep. -

APJ Autumn 2007

AUTUMN 2007 "There's no money in poetry, but then there's no poetry in money, either." ~Robert Graves About the Poets Page 7 Credits Page 9 Big Thicket Song #3 Big Thicket Song #1 For Jame Byrd, Jr. Seven miles from the highway, down trails truckling through cypress trees— Blacktop yellow stripe down the middle the sun a hint of fire edging the leaves— they dragged a living man down a family of beavers builds a home. Never down until they dragged a dead man broken into pieces enough to participate from the bank of tooth- and tail-crafted pond, I shed on either side, tall pines, planted shirt and pants, strip to bare truth every ten years pulped after growth and wade into brown water, mists tall enough to mill the paper to publish the obituary still rising in the stippled day. Toes squish through ripe mud, bubbles ooze up. these woods have a dead man in them Sink down, descend days and years, broken shredded into black asphalt into first light. Sunlight, banding in waves, head legs torso scattered like needles deep woods whisper here breaks into thin beams between leaves and falling, falling, splatters knees a thousand people drive over red specks and belly, chest, penis, pale buttocks, spread droplets of raging tears but paints the years. Only the sounds a dead man’s dying cannot roll dark thicket into shining light of splashing, rap of a woodpecker on dry bark, rustle of armadillos rooting through damp leaves, breath heavy, alien. So and, again, so. A white heron, immense in beauty, © 2007 H.