Effects of Development on Indigenous Dietary Pattern: a Nigerian Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

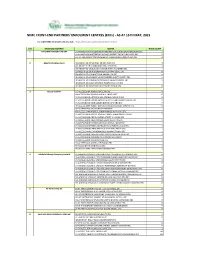

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Spatial Pattern of Housing Quality in Abuja, Nigeria

International Journal of Coal, Geology and Mining Research Vol.2, No.1, pp.1-20, May 2020 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK(www.eajournals.org) SPATIAL PATTERN OF HOUSING QUALITY IN ABUJA, NIGERIA Saliman Dauda Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Baze University, Abuja, Nigeria ABSTRACT: The study attempted evaluation of Spatial Pattern of Housing Quality of Abuja, Nigeria. The identified 62 political wards were stratified into their various Area Councils namely, Abuja Municipal Area Council (AMAC), Bwari Area Council, Gwagwalada Area Council, KwaliArea Council, Kuje Area Council and Abaji Area Council. Using systematic random sampling, 3593, 1002,641,290,341 and 202 houses were selected in AMAC, Bwari Area Council, Gwagwalada Area Council, Kwali Area Council, Kuje Area Council and Abaji Area Council respectively to give a total of 6069 houses. Socioeconomic characteristics of the households revealed that the youth constituted 14.2% of the respondents, while 79.99% of the respondents were also found to be in the age bracket of 31-60 years. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) confirmed, that there were significant differences in the age distribution of the residents (F = 4.11, p = 0.005). Analysis of spatial pattern of housing quality using Factor Analysis revealed that housing location quality attributes factor, recorded highest influence on the spatial pattern of housing quality in Area Councils, such as AMAC, Bwari Area Council and Gwagwalada Area Council. The study concluded that a general hierarchical trend in spatial pattern of housing quality had been figured out in Abuja, where housing quality was observed to decrease with increase in distance from the Central Business District(CBD). -

Frugivorous Bird Species Diversity in Relation to the Diversity of Fruit

ISBN: 2141 – 1778 jfewr ©2016 - jfewr Publications E-mail:[email protected] 80 FRUGIVOROUS BIRD SPECIES DIVERSITY IN RELATION TO THE DIVERSITY OF FRUIT TREE SPECIES IN RESERVED AND DESIGNATED GREEN AREAS IN THE FEDERAL CAPITAL TERRITORY, NIGERIA 1Ihuma, J.O; Tella, I. O2; Madakan, S. P.3 and Akpan, M2 1Department of Biological Sciences, Bingham University, P.M.B. 005, Karu, Nasarawa State, Nigeria Email:[email protected] 2Federal University of Technology, Yola, Nigeria, Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management. 3University of Maiduguri, Borno, Nigeria, Department of Biological Sciences ABSTRACT The diversity of frugivorous bird species in relation to tree species diversity was investigated in Designated and Reserved Green Areas of Abuja, Nigeria. The study estimated, investigated and examined trees species and avian frugivore in terms of their diversity. Point-Centered Quarter Method (PCQM) was used for vegetation analysis while random walk and focal observation was used for bird frugivore identification and enumeration. data was collected from six locations coinciding with the local administrative areas within the Federal Capital Territory. These were, the Abuja Municipal Area Council (AMAC), Abaji, Bwari, Gwagwalada, Kuje and Kwali. AMAC is designated as urban while the remaining five sites are designated as sub-urban. The highest number of fruit tree species was encountered in AMAC (30), followed by Abaji (29) while 27, 25, 19 and 11 fruit tree species were encountered in Kwali, Bwari Gwagwalada and Kuje respectively. The similarity or otherwise dissimilarity in fruit tree species composition between each pair of the enumerated sites showed Gwagwalada and Kuje as the most similar, and the similarity or otherwise dissimilarity in frugivorous bird species composition between each pair of the enumerated showed higher species similarity between the AMAC and each of the other sites, and between each pair of the sites than that of the fruit trees in the respective sites. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Climate Change Perception Among Geography and Biology Teachers in Gwagwalada Area Council of the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria

Annals of Ecology and Environmental Science Volume 2, Issue 4, 2018, PP 1-11 ISSN 2637-5338 Climate Change Perception among Geography and Biology Teachers in Gwagwalada Area Council of the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria Ishaya S., Apochi, M. A and Mohammed Abdullahi Hassan Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Abuja, Nigeria. *Corresponding Author: Ishaya S, Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Abuja, Nigeria. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study assess climate change perception among Geography and Biology teachers in Gwagwalada Area Council of the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria. In carrying out this study, the Interpretive Research method was utilized. The population targeted were the forty nine geography and biology teachers in the eight public senior secondary schools in the Area Council. Semi-structured questionnaire was used in this study. Findings of the study shows that all geography and biology science teachers from the studied schools affirmed to changes in climate/ The main indicators of climate change as observed by the teachers are temperature rise, decrease in rainfall, drier weather, decline in domestic water supply, incapacitation of crop production, de-vegetation, decline of pastures for livestock production thereby instigated conflicts between headers and farmers and rural-urban migration. Reforestation, afforestation, cultivating drought tolerant crops, encouraging irrigation/fadama farming in localities, improve in water usage, shortening growing season by cultivation varieties that matured within a short period of time and indebt dissemination of information on potential weather incidences/events/disasters where seen as strategies of combating climate change impacts as opined by the teachers. -

Developing the Knowledge, Skills and Talent of Youth to Further Food Security and Nutrition

DEVELOPING THE KNOWLEDGE, SKILLS AND TALENT OF YOUTH TO FURTHER FOOD SECURITY AND NUTRITION The following case study was received as a result of a call issued by the Committee on World Food Security for case studies highlighting examples of initiatives aimed at ‘Developing the knowledge, skills and talent of youth to further food security and nutrition’. The cases received provide the background for a discussion of lessons learned and potential policy implications at a special event on October 15th, 2015 during CFS 42. Find out more at www.fao.org/cfs/youth. Background The registrations of farmers in the Federal Capital Territory in which to encourage the timely distribution of farming input, e.g The Fertilizers and the seedlings and other Agricultural inputs both to the youth and the adult, and the documentations of the various exercises in the facilitation of food distribution, nutrition development and encouraged the farmers to get access to farming input and cultivation of land which is being done in the Five areas council of the Federal Capital Territory Abuja, Nigeria ,Municipal , Gwagwalada, Abaji, Kwali , Bwari. Selected Schools were taken and farmers which includes youth were asked to go and register their names and documentation of some information. This is done with the help of the Agricultural Development Programe , International Fertilizers Development company and Michael Adedotun Oke Foundation. And a data of farmers were produce. Challenges Most of the youths that came for the farmers registration does not have the necessary identification to been register during the period. The cost of moving to the registration centre’s as a great implication of the youth due to the cost implications. -

Rainfall Variations As the Determinant of Malaria in the Federal Capital Territory Abuja, Nigeria

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Environment and Earth Science www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3216 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0948 (Online) Vol.4, No.20, 2014 Rainfall Variations as the Determinant of Malaria in the Federal Capital Territory Abuja, Nigeria Yahaya Usman Badaru 1* Akiode Olukemi Adejoke 2 Ahmed Sadauki Abubakar 3 Mohammed Ahmed Emigilati 4 1. Applied Remote Sensing Laboratory, Department of Geography, School of Natural and Applied Science 2. Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria 3. University of Abertay, Dundee, Scotland-UK 4. Department of Geography, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria 5. Department of Geography, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria *Emails of the corresponding authors : [email protected] ; [email protected] Abstract This study highlights the increasing interest in identifying the parameters adequate to measure rainfall and wet day’s variations as the determinant of malaria occurrences and distribution for a period of twelve months (2012) in the Federal Capital Territory. Satellite data were developed to identify malaria risk area and to evaluate amounts of rainfall and the durations of wet or rainy days conducive to malaria outbreaks at appropriate scales. Secondly, the studies examine the correlation of monthly and annual malaria cases, and rainfall amounts, including wet days with a lag time of one year. The result of correlation analysis shows that relationship exists between the observed weather variables and malaria. The coefficients of determination R2 of rainfall influencing malaria is 0.3109 (31.1%) and wet days influencing malaria is 0.3920 (39.2%). -

The Underutilized Vegetable Plants of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) Abuja of Nigeria

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals International Journal of Development and Sustainability Online ISSN: 2168-8662 – www.isdsnet.com/ijds Volume 1 Number 3 (2012): Pages 634-643 ISDS Article ID: IJDS12091801 Special Issue: Development and Sustainability in Africa – Part 1 The underutilized vegetable plants of the federal capital territory (FCT) Abuja of Nigeria S. Abubakar 1*, G.H. Ogbadu 1, A.B. Usman 1, O. Segun 2, O. Olorode 2, I.U. Samirah 3 1 Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Advanced Laboratory, Sheda Science and Technology Complex, P.M.B. 186, Garki, Abuja FCT, Nigeria 2 Department of Biological Science University of Abuja P.M.B 117. Abuja FCT, Nigeria 3 Department of biological science F.C.E. Zuba, P.M.B. 61. Garki, Abuja, Nigeria. Abstract Promotion and conservation of underutilized indigenous vegetable plants for healthy diet, income generation and food security are the main aims of this ecological survey. Sixty species of flowering plants underutilized as vegetables were collected from the field in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), across all the six area councils). The family Fabaceae has the highest number of species followed by Asteraceae. Thirty four (56.7%), of the vegetables are herbs, twenty (33.3%) are trees, while six (10%) species are shrubs. The predominant modes of propagation among the plants are by seeds, followed by stem cutting and of course few are by underground parts of the plants. Seventy percent (70%) of the underutilized vegetables collected are wild, while thirty percent (30%) are less cultivated. -

List of Candidates FCT Area Council Election 12 February 2022

Final List of Candidates FCT Area Council Election 12 February 2022 www.inecnigeria.org FCT AreaCouncil Elections 3 Table of Contents 03 Introduction 04 Abaji AMAC 10 Bwari 24 35 Gwagwalada Kuje 46 Kwali 52 Summary 58 FCT AreaCouncil Elections 2 Introduction The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) is empowered by Section 103(1) of the Electoral Act 2010 (as amended) to conduct elections into the offices of Chairman, Vice Chairman and members of the Area Councils of the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). Pursuant to this power, the Commission will conduct elec- tion into these positions in the FCT Area Councils on Saturday 12th February 2022. In furtherance of the Commission’s continued effort to make information on the candidates contesting for elections available to Nigerians as required by Section 34 of the Electoral Act, this booklet provides detailed information on the particu- lars of candidates for the 2022 FCT Area Council election: their political parties, age, gender, disability status and educational qualifications. The FCT Area Council has a total of 68 constituencies for 6 chairmen and 62 coun- cillors. The election to the chairmanship positions will be contested by 55 candi- dates (52 male and 3 female) while the vice-chairmanship consists of 47 male and 8 female candidates sponsored by 14 political parties. The 363 candidates contest- ing for the councillorship positions consist of 332 males and 31 female contestants. Overall, some 473 candidates and their running mates are vying for 68 elective positions in the FCT. In addition to this booklet, the list is also published in the Commission’s FCT office as well as our website and social media platforms both as a legal requirement and for public information. -

Trending Spatial Pattern of Solid Waste Disposal and Health Risks Associated with It in the Rural Areas: an Example from Kuje Area Council, Nigeria

Annals of Geographical Studies Volume 3, Issue 1, 2020, PP 6-12 ISSN 2642-9136 Trending Spatial Pattern of Solid Waste Disposal and Health Risks Associated with it in the Rural Areas: An Example from Kuje Area Council, Nigeria Akanbi, Oluwatoyin Adewuyi1*, Adekiya, Oyelayo Abike2 1Department of Geography & Environment Management, University of Abuja, Gwagwalada, Abuja, Nigeria 2University of Abuja, Gwagwalada, Abuja, Nigeria *Corresponding Author: Akanbi, Oluwatoyin Adewuyi, Department of Geography & Environment Management, University of Abuja, Gwagwalada, Abuja, Nigeria, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT In recent time, wastes management has remained a major concern to both government and larger society. This emanates from anthropogenic activities and continuous population growth with its health attendant problems. Rural areas of most developing countries are faced with health associated with it with its attendant health problems. The study adopts random sampling method; the data were subjected to correlation analysis. A total of 396 respondents were randomly sampled across all the randomly selected wards in the study area with the tools of questionnaire and in-depth interview (IDI). Data collected were subjected to correlation analysis. With the p-value of .182 > 0.05 level of significance at a correlation level of 0.343 at 22 df, there is a weak relationship between spatial pattern of waste disposal and health risks in the rural areas of Kuje Area Council of FCT, Nigeria. In the light of this, the study recommends among others that, inculcation of relevant environmental education, introduction of necessary legislation and the need for attitudinal change towards waste disposal on the part of rural populace. -

Abuja, Nigeria

IOSR Journal of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 7, Series 1 (July. 2020) 49-60 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Vehicular Traffic Congestion in Selected Satellite Towns in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) Abuja, Nigeria ALPHONSUS NWACHUKWU ALI And GRACE CHIDERA, NGENE, Department Of Geography, University Of Nigeria Nsukka ABSTRACT Purpose This paper investigated the level and causes of traffic congestion in FCT Abuja, as it affects commuters from satellite towns as they commute daily to the city centre. This is because previous studies did not consider traffic congestion situation in the satellite towns of the city.: Design/Methodology/Approach: To achieve this aim, six traffic congested roads linking satellite towns and AMAC were sampled for this study.. The primary data for this work were obtained through administration of 655 copies of questionnaire to respondents across the study area. Data on vehicular traffic counts along the 6 sampled roads linking satellite towns and AMAC for 7days, were collected from FRSC Abuja Command. Descriptive statistics and graph theoretic indices were used to analyze the level, causes of traffic congestion and road network connectivity. Findings: The study revealed the level of vehicular traffic congestion which varied from 5.3% above the designated road capacity in Kugbo to 96.1% in Nyanya. The major causes of traffic congestion were found to be the size of available road capacity, dismal condition of roads, market activity along the side of roads, poor road network connectivity and roadside parking of vehicles Practical Implications: The results may be used to develop strategic transport land use planning, aimed at improving road connectivity and capacity to reducing vehicular traffic congestion inherent in satellite towns, as well as enhancing road transport efficiency between city centre and its adjoining peripheral highly populated satellite towns. -

A Case of Gwagwalada Town, Gwagwalada Area Council Federal Capital Territory (Fct), Nigeria

Journal of Ecology & Natural Resources ISSN: 2578-4994 Water Vendor and Domestic Water Needs in Peri-Urban: A Case of Gwagwalada Town, Gwagwalada Area Council Federal Capital Territory (Fct), Nigeria Omotoso O1* and Akanbi OA2 Research article 1 Department of Geography & Planning Science, Ekiti State University, Nigeria Volume 2 Issue 6 2Department of Geography & Environment Management, University of Abuja, Nigeria Received Date: October 17, 2018 Published Date: November 16, 2018 *Corresponding author: Omotoso Oluwatuyi, Department of Geography & Planning DOI: 10.23880/jenr-16000149 Science, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria, Tel: 08035749120; Email: [email protected] Abstract Water is a major determinant of status of human existence and its socio-economic activities. This is partly due to its role in stemming growing trend in water-borne diseases with its attendant problems. However, the availability of potable water in the areas varies from those in the urban area. The urban areas enjoy more of potable water than the rural areas. In FCT, Nigeria the number of people outweigh the available potable water, thus people are forced to look for water for their needs through various methods, including water vendor. Water vendor is an unconventional method of sourcing water involving the use of truck, plastic container among others. The study involved 400 respondents in Gwagwalada Area Council, FCT- Nigeria. In all, interviews were conducted and questionnaires were also administered in the randomly selected settlements of the wards on the subject matter. Data from all these sources were subjected to simple descriptive statistic of simple chi-square analysis. The result shows that, table value is X20.05, 9=16.9, while the calculated value is 0.25; there is no significant relationship between water vendor and water needs of people of Gwagwalada Area Council, FCT-Nigeria.