Amer Dardağan Neoplatonic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RELG 399 Fall2019

McGill University School of Religious Studies RELG 399 TEXTS OF CHRISTIAN SPIRITUALITY (Late Antiquity) In the Fall Term of 2019 this seminar course will focus on Christian spirituality in Late Antiquity with close study and interpretation of Aurelius Augustine’s spiritual odyssey the Confessiones, his account of creation in De genesi ad litteram, and his handbook of hermeneutics De doctrina Christiana. We will also read Ancius Manlius Severinus Boethius’s treatment of theodicy in De consolatione philosophiae, his De Trinitate, and selections from De Musica. Professor: Torrance Kirby Office Hours: Birks 206, Tuesdays/Thursdays, 10:00–11:00 am Email: [email protected] Birks Building, Room 004A Tuesdays/Thursdays 4:05–5:25 pm COURSE SYLLABUS—FALL TERM 2019 Date Reading 3 September INTRODUCTION 5 September Aurelius Augustine, Confessiones Book I, Early Years 10 September Book II, Theft of Pears 12 September Book III, Adolescence and Student Life 17 September Book IV, Manichee and Astrologer 19 September Book V, Carthage, Rome, and Milan *Confirm Mid-Term Essay Topics (1500-2000 words) (NB Consult the Style Sheet, essay-writing guidelines and evaluation rubric in the appendix to the syllabus.) 24 September Book VI, Secular Ambitions and Conflicts 26 September Book VII, Neoplatonic Quest for the Good 1 October Book VIII, Tolle, lege; tolle, lege 3 October Book IX, Vision at Ostia 8 October Book X, 1-26 Memory *Mid-term Essays due at beginning of class. Essay Conferences to be scheduled for week of 21 October 10 October Book X, 27-43 “Late have I loved you” 15 October Book XI, Time and Eternity 17 October Book XII, Creation Essay Conferences begin this week, Birks 206. -

On the Present-Day Veneration of Sacred Trees in the Holy Land

ON THE PRESENT-DAY VENERATION OF SACRED TREES IN THE HOLY LAND Amots Dafni Abstract: This article surveys the current pervasiveness of the phenomenon of sacred trees in the Holy Land, with special reference to the official attitudes of local religious leaders and the attitudes of Muslims in comparison with the Druze as well as in monotheism vs. polytheism. Field data regarding the rea- sons for the sanctification of trees and the common beliefs and rituals related to them are described, comparing the form which the phenomenon takes among different ethnic groups. In addition, I discuss the temporal and spatial changes in the magnitude of tree worship in Northern Israel, its syncretic aspects, and its future. Key words: Holy land, sacred tree, tree veneration INTRODUCTION Trees have always been regarded as the first temples of the gods, and sacred groves as their first place of worship and both were held in utmost reverence in the past (Pliny 1945: 12.2.3; Quantz 1898: 471; Porteous 1928: 190). Thus, it is not surprising that individual as well as groups of sacred trees have been a characteristic of almost every culture and religion that has existed in places where trees can grow (Philpot 1897: 4; Quantz 1898: 467; Chandran & Hughes 1997: 414). It is not uncommon to find traces of tree worship in the Middle East, as well. However, as William Robertson-Smith (1889: 187) noted, “there is no reason to think that any of the great Semitic cults developed out of tree worship”. It has already been recognized that trees are not worshipped for them- selves but for what is revealed through them, for what they imply and signify (Eliade 1958: 268; Zahan 1979: 28), and, especially, for various powers attrib- uted to them (Millar et al. -

Mysticism in Indian Philosophy

The Indian Institute of World Culture Basavangudi, Bangalore-4 Transaction No.36 MYSTICISM IN INDIAN PHILOSOPHY BY K. GOPALAKRISHNA RAO Editor, “Jeevana”, Bangalore 1968 Re. 1.00 PREFACE This Transaction is a resume of a lecture delivered at the Indian Institute of World Culture by Sri K. Gopala- Krishna Rao, Poet and Editor, Jeevana, Bangalore. MYSTICISM IN INDIAN PHILOSOPHY Philosophy, Religion, Mysticism arc different pathways to God. Philosophy literally means love of wisdom for intellectuals. It seeks to ascertain the nature of Reality through sense of perception. Religion has a social value more than that of a spiritual value. In its conventional forms it fosters plenty but fails to express the divinity in man. In this sense it is less than a direct encounter with reality. Mysticism denotes that attitude of mind which involves a direct immediate intuitive apprehension of God. It signifies the highest attitude of which man is capable, viz., a beatific contemplation of God and its dissemination in society and world. It is a fruition of man’s highest aspiration as an integral personality satisfying the eternal values of life like truth, goodness, beauty and love. A man who aspires after the mystical life must have an unfaltering and penetrating intellect; he must also have a powerful philosophic imagination. Accurate intellectual thought is a sure accompaniment of mystical experience. Not all mystics need be philosophers, not all mystics need be poets, not all mystics need be Activists, not all mystics lead a life of emotion; but wherever true mysticism is, one of these faculties must predominate. A true life of mysticism teaches a full-fledged morality in the individual and a life of general good in the world. -

The Language of Union in Jewish Neoplatonism

Chapter 5 “As Light Unites with Light”: The Language of Union in Jewish Neoplatonism Like their Christian and Muslim counterparts, Jewish writers between the 10th and 13th centuries increasingly expressed the soul’s transformation and prog- ress towards God in Platonic, Neoplatonic, and Neo-Aristotelian terms. These philosophical systems provided models that not only allowed the human soul to come close to God, but also enabled union with Him, through mediating spiritual or mental elements. In the early writings of Jewish Neoplatonists, under the direct influence of Arab Neoplatonism, the notion of mystical union was articulated for the first time since Philo. The Neoplatonist “axis of return”, which constitutes the odyssey of the soul to its origin in the divine, became creatively absorbed into rabbinic Judaism. Judaism was synthesized once again with Platonism, this time in the form of the Platonism of Proclus and Plotinus and their enhanced idea and experience of mystical henōsis with the “Nous” and the “One”.1 In their classic study on Isaac Israeli (855–955),2 Alexander Altmann and Samuel Stern, claimed that this 10th-century Jewish-Arab Neoplatonist artic- ulated for the first time a Jewish-Arabic version of henōsis as ittihad. In his Neoplatonic understanding of Judaism, Isaac Israeli incorporated the ideas of spiritual return and mystical union into his systematic exposition of rabbinic Judaism. Israeli interpreted this spiritual return as a religious journey, and viewed the three stages of Proclus’s ladder of ascension—purification, illumi- nation, and mystical union—as the inner meaning of Judaism and its religious path. His synthesis paved the way for the extensive employment of the termi- nology of devequt—but significantly, in the Neoplatonic sense of henōsis—in medieval Jewish literature, both philosophical and Kabbalistic. -

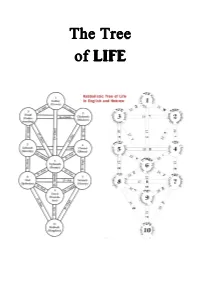

The Hexagonal Geometry of the Tree of Life July 5, 2008

The Hexagonal Geometry of the Tree of Life July 5, 2008 The Hexagonal Geometry Of the Tree of Life By Patrick Mulcahy This short treatise explores (using polyhex mathematics) the special relationship that exists between the kabbalistic Tree of Life diagram and the geometry of the simple hexagon. It reveals how the ten sefirot and the twenty- two pathways of the Tree of Life are each individually and uniquely linked to the hexagonal form. The Hebrew alphabet is also shown to be esoterically associated with the geometry of the hexagon. This treatise is intended to be a primer for the further study and esoteric application of polyhex mathematics. First Edition (Expanded) Copyright 2008 © Patrick Mulcahy AstroQab Publishing 2008 Email: [email protected] Website: http://members.optusnet.com.au/~astroqab 2 The Hexagonal Geometry of the Tree of Life July 5, 2008 Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................................. 6 General Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 Introduction to the Polyhex Tree of Life ................................................................................ 9 The Polyhex Tree of Life ...................................................................................................... 13 The Three Highest Sefirot ................................................................................................ 13 The Seven Lower -

Summary Essay"

Muhammad Abdullah (19154) Book 4 Chapter 5 "Summary Essay" This chapter on 'The Peripatetic School' talks about this school and its decline. By 'peripatetic', it means the school of thought of Aristotle. Moreover, 'The Peripatetic School' was a philosophy school in Ancient Greece. And obviously its teachings were found and inspired by Aristotle. Other than that, its followers were called, 'Peripatetic'. At first, the school was a base for Macedonian influence in Athens. The school in earlier days -and in Aristotle's times- was distinguished by doing research in every field, like, botany, zoology, and many more. It tried to solve problems in every subject/field. It also gathered earlier views and writings of philosophers who came before. First, it talks about the difference in botanical writings of Theophrastus and Aristotle. Theophrastus was the successor of Aristotle in the Peripatetic School. He was a plant biologist. Theophrastus wrote treatises in many areas of philosophy to improve and comment-on Aristotle's writings. In addition to this, Theophrastus built his own writings upon the writings of earlier philosophers. The chapter then differentiates between Lyceum (The Peripatetic School) and Ptolemaic Alexandria. Moreover, after Aristotle, Theophrastus and Strato shifted the focus of peripatetic philosophy to more of empiricism and materialism. One of Theophrastus' most important works is 'Metaphysics' or 'A Fragment'. This work is important in the sense that it raises important questions. This work seems to object Aristotle's work of Unmoved Mover. Theophrastus states that there's natural phenomenon at work. However, some interpretations suggest that Theophrastus goes against Platonist. Theophrastus says, "...the universe is an organized system in which the same degree of purposefulness and goodness should not be expected at every level." Additionally, the chapter points out that objecting the writings and building your own work upon it is what the 'real' Aristotelian way of doing work is. -

The Tree of LIFE

The Tree of LIFE ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ ~ 4 ~ Trees of Life. From the highest antiquity trees were connected with the gods and mystical forces in nature. Every nation had its sacred tree, with its peculiar characteristics and attributes based on natural, and also occasionally on occult properties, as expounded in the esoteric teachings. Thus the peepul or Âshvattha of India, the abode of Pitris (elementals in fact) of a lower order, became the Bo-tree or ficus religiosa of the Buddhists the world over, since Gautama Buddha reached the highest knowledge and Nirvâna under such a tree. The ash tree, Yggdrasil, is the world-tree of the Norsemen or Scandinavians. The banyan tree is the symbol of spirit and matter, descending to the earth, striking root, and then re-ascending heavenward again. The triple- leaved palâsa is a symbol of the triple essence in the Universe - Spirit, Soul, Matter. The dark cypress was the world-tree of Mexico, and is now with the Christians and Mahomedans the emblem of death, of peace and rest. The fir was held sacred in Egypt, and its cone was carried in religious processions, though now it has almost disappeared from the land of the mummies; so also was the sycamore, the tamarisk, the palm and the vine. The sycamore was the Tree of Life in Egypt, and also in Assyria. It was sacred to Hathor at Heliopolis; and is now sacred in the same place to the Virgin Mary. Its juice was precious by virtue of its occult powers, as the Soma is with Brahmans, and Haoma with the Parsis. -

Aquinas on Attributes

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by MedievaleCommons@Cornell Philosophy and Theology 11 (2003), 1–41. Printed in the United States of America. Copyright C 2004 Cambridge University Press 1057-0608 DOI: 10.1017/S105706080300001X Aquinas on Attributes BRIAN LEFTOW Oriel College, Oxford Aquinas’ theory of attributes is one of the most obscure, controversial parts of his thought. There is no agreement even on so basic a matter as where he falls in the standard scheme of classifying such theories: to Copleston, he is a resemblance-nominalist1; to Armstrong, a “concept nominalist”2; to Edwards and Spade, “almost as strong a realist as Duns Scotus”3; to Gracia, Pannier, and Sullivan, neither realist nor nominalist4; to Hamlyn, the Middle Ages’ “prime exponent of realism,” although his theory adds elements of nominalism and “conceptualism”5; to Wolterstorff, just inconsistent.6 I now set out Aquinas’ view and try to answer the vexed question of how to classify it. Part of the confusion here is terminological. As emerges below, Thomas believed in “tropes” of “lowest” (infima) species of accidents and (I argue) substances.7 Many now class trope theories as a form of nominalism,8 while 1. F. C. Copleston, Aquinas (Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books, 1955), P. 94. 2. D. M. Armstrong, Nominalism and Realism (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 25, 83, 87. Armstrong is tentative about this. 3. Sandra Edwards, “The Realism of Aquinas,” The New Scholasticism 59 (1985): 79; Paul Vincent Spade, “Degrees of Being, Degrees of Goodness,” in Aquinas’ Moral Theory, ed. -

The Univocity of Substance and the Formal Distinction of Attributes: the Role of Duns Scotus in Deleuze's Reading of Spinoza Nathan Widder

parrhesia 33 · 2020 · 150-176 the univocity of substance and the formal distinction of attributes: the role of duns scotus in deleuze's reading of spinoza nathan widder This paper examines the role played by medieval theologian John Duns Scotus in Gilles Deleuze’s reading of Spinoza’s philosophy of expressive substance; more generally, it elaborates a crucial moment in the development of Deleuze’s philosophy of sense and difference. Deleuze contends that Spinoza adapts and extends Duns Scotus’s two most influential theses, the univocity of being and formal distinction, despite neither appearing explicitly in Spinoza’s writings. “It takes nothing away from Spinoza’s originality,” Deleuze declares, “to place him in a perspective that may already be found in Duns Scotus” (Deleuze, 1992, 49).1 Nevertheless, the historiographic evidence is clearly lacking, leaving Deleuze to admit that “it is hardly likely that” Spinoza had even read Duns Scotus (359n28). Indeed, the only support he musters for his speculation is Spinoza’s obvious in- terests in scholastic metaphysical and logical treatises, the “probable influence” of the Scotist-informed Franciscan priest Juan de Prado on his thought, and the fact that the problems Duns Scotus addresses need not be confined to Christian thought (359–360n28). The paucity of evidence supporting this “use and abuse” of history, however, does not necessarily defeat the thesis. Like other lineages Deleuze proposes, the one he traces from Duns Scotus to Spinoza, and subsequently to Nietzsche, turns not on establishing intentional references by one thinker to his predecessor, but instead on showing how the borrowings and adaptations asserted to create the connec- tion make sense of the way the second philosopher surmounts blockages he faces while responding to issues left unaddressed by the first. -

Intellectual Elitism and the Need for Faith in Maimonides and Aquinas

INTELLECTUAL ELITISM AND THE NEED FOR FAITH Intellectual elitism and the need for faith in Maimonides and Aquinas Elitismo intelectual y la necesidad de la fe según Maimónides y Tomás de Aquino FRANCISCO ROMERO CARRASQUILLO Departamento de Humanidades Universidad Panamericana 45010 Zapopan, Jalisco (México) [email protected] Abstract: In his Commentary on Boethius’ De Resumen: En su Comentario al De Trinitate de Trinitate 3.1, Aquinas cites Maimonides as Boecio 3.1, Tomás de Aquino cita a Maimóni- giving fi ve reasons for the need for faith. Yet des, de quien afi rma que presenta cinco ra- interpreters tend to see Aquinas as “stand- zones a favor de la necesidad de la fe. Los in- ing Maimonides on his head”. In this paper, térpretes suelen ver a Tomás de Aquino como the author places Maimonides’ text (on the si “hubiera puesto a Maimónides de cabeza”. five reasons for concealing metaphysics) En el presente artículo se retoma el texto de within the context of his rational mysticism Maimónides (acerca de las cinco razones por and compares it to Aquinas’ own Christian las que la metafísica debe reservarse a los mystical thought in an attempt to show that doctos y ocultarse a las masas), y se sitúa en el in his own mind Aquinas is not misquoting, contexto de su misticismo racional. Compa- reversing, or doing violence to Maimonides’ rándolo con el pensamiento místico cristiano text; rather, Aquinas is completing Maimon- de Tomás de Aquino, se muestra cómo éste ides’ natural, rational mysticism with what he no está citando erróneamente, ni invirtiendo understands to be the supernatural perfec- ni violentando el texto de Maimónides; más tion of the theological virtue of faith. -

Index Nominum

Index Nominum Abualcasim, 50 Alfred of Sareshal, 319n Achillini, Alessandro, 179, 294–95 Algazali, 52n Adalbertus Ranconis de Ericinio, Ali, Ismail, 8n, 132 205n Alkindi, 304 Adam, 313 Allan, Mowbray, 276n Adam of Papenhoven, 222n Alne, Robert, 208n Adamson, Melitta Weiss, 136n Alonso, Manual, 46 Adenulf of Anagni, 301, 384 Alphonse of Poitiers, 193, 234 Adrian IV, pope, 108 Alverny, Marie-Thérèse d’, 35, 46, Afonso I Henriques, king of Portu- 50, 53n, 93, 147, 177, 264n, 303, gal, 35 308n Aimery, archdeacon of Tripoli, Alvicinus de Cremona, 368 105–6 Amadaeus VIII, duke of Savoy, Alberic of Trois Fontaines, 100–101 231 Albert de Robertis, bishop of Ambrose, 289 Tripoli, 106 Anastasius IV, pope, 108 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Anti- Anatoli, Jacob, 113 och, 73, 77n, 86–87, 105–6, 122, Andreas the Jew, 116 140 Andrew of Cornwall, 201n Albert of Schmidmüln, 215n, 269 Andrew of Sens, 199, 200–202 Albertus Magnus, 1, 174, 185, 191, Antonius de Colell, 268 194, 212n, 227, 229, 231, 245–48, Antweiler, Wolfgang, 70n, 74n, 77n, 250–51, 271, 284, 298, 303, 310, 105n, 106 315–16, 332 Aquinas, Thomas, 114, 256, 258, Albohali, 46, 53, 56 280n, 298, 315, 317 Albrecht I, duke of Austria, 254–55 Aratus, 41 Albumasar, 36, 45, 50, 55, 59, Aristippus, Henry, 91, 329 304 Arnald of Villanova, 1, 156, 229, 235, Alcabitius, 51, 56 267 Alderotti, Taddeo, 186 Arnaud of Verdale, 211n, 268 Alexander III, pope, 65, 150 Ashraf, al-, 139n Alexander IV, pope, 82 Augustine (of Hippo), 331 Alexander of Aphrodisias, 311, Augustine of Trent, 231 336–37 Aulus Gellius, -

Bibliography on Medieval Logic: General Works a - K

Bibliography on Medieval Logic: General Works A - K https://www.historyoflogic.com/biblio/logic-medieval-biblio.htm History of Logic from Aristotle to Gödel by Raul Corazzon | e-mail: [email protected] Selected Bibliography on Medieval Logic: General Studies. (First Part: A - K) BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. Amerini, Fabrizio. 2000. "La Dottrina Della Significatio Di Francesco Da Prato O.P. (Xiv Secolo). Una Critica Tomista a Guglielmo Di Ockham." Documenti e Studi sulla Tradizione Filosofica Medievale no. XI:375-408. 2. Angelelli, Ignacio. 1993. "Augustinus Triumphus' Alleged Destructio of the Porphyrian Tree." In Argumentationstheorie. Scholastische Forschungen Zu Den Logischen Und Semantischen Regeln Korrekten Folgerns, edited by Jacobi, Klaus, 483-489. Leiden: Brill. 3. Bertagna, Mario. 2000. "La Dottrina Delle Conseguenze Nella "Logica" Di Pietro Da Mantova." Documenti e Studi sulla Tradizione Filosofica Medievale no. 11:459-496. 4. Beuchot, Mauricio. 1979. "La Filosofia Del Lenguaje De Pedro Hispano." Revista de Filosofia (Mexico) no. 12:215-230. 5. Boh, Ivan. 1964. "An Examination of Some Proofs in Burleigh's Propositional Logic." New Scholasticism no. 38:44-60. 6. ———. 1984. "Propositional Attitudes in the Logic of Walter Burley and William Ockham." Franciscan Studies:31-59. 7. ———. 1991. "Bradwardine's (?) Critique of Ockham's Modal Logic." In Historia Philosophiae Medii Aevi. Studien Zur Geschichte Der Philosophie Des Mittelalters. Festschrift Für Kurt Flasch Zu Seinem 60. Geburtstag. (Vol. I), edited by Mojsisch, Burkhard and Pluta, Olaf, 55-70. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: B. R. Grüner. 8. Braakhuis, Henk Antonius. 1977. "The Views of William of Sherwood on Some Semantical Topics and Their Relation to Those of Roger Bacon." Vivarium no.