A History of Ottoman Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super! Drama TV April 2021

Super! drama TV April 2021 Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese 2021.03.29 2021.03.30 2021.03.31 2021.04.01 2021.04.02 2021.04.03 2021.04.04 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:00 #15 #17 #19 #21 「The Long Morrow」 「Number 12 Looks Just Like You」 「Night Call」 「Spur of the Moment」 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 #16 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 TWILIGHT ZONE Season 5 06:30 「The Self-Improvement of Salvadore #18 #20 #22 Ross」 「Black Leather Jackets」 「From Agnes - With Love」 「Queen of the Nile」 07:00 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 CRIMINAL MINDS Season 10 07:00 07:00 STAR TREK Season 1 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS 07:00 #1 #2 #20 #19 「X」 「Burn」 「Court Martial」 「DANGER AT OCEAN DEEP」 07:30 07:30 07:30 08:00 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 THUNDERBIRDS 08:00 10 10 #1 #20 #13「The Romance Recalibration」 #15「The Locomotion Reverberation」 「bitter harvest」 「MOVE- AND YOU'RE DEAD」 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 08:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 08:30 10 #14「The Emotion Detection 10 12 Automation」 #16「The Allowance Evaporation」 #6「The Imitation Perturbation」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 THE GREAT 09:30 SUPERNATURAL Season 14 09:30 09:30 BETTER CALL SAUL Season 3 09:30 ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

The Natural History Topography

THE NATURAL HISTORY AND THE TOPOGRAPHY OF GROTON, MASSACHUSETTS TOGETHER WITH OTHER MATTER RELATING TO THE HISTORY OF. THE TOWN BY SAMUEL ABBOTT GREEN Facts lie at the foundation of history, and they are the raw material of all narrative writing GROTON: 1912 fflnibnsitJ! ~ms :_ JOHN WILSON AND SON, CAM:SRIDGE, C. S. A. OF SAMUEL AUGUSTUS SHATTUCK AND HIS WIFE SARAH PARKER SHATTUCK -BOTH NATIVES OF THE TOWN- WITH WHOM MY PERSONAL ASSOCIATIONS DURING THE LATER YEARS OF THEIR LIVES WERE ALWAYS SO PLEASANT THESE PAGES ARE INSCRIBED INTRODUCTORY NO.TE. WITH the exception of Miss Elizabeth Sewall Hill's paper on the Flora and Fauna of the town, and of a very few others that were first printed in newspapers, these several articles have already appeared in the Gro~on Historical Series. In the present forn1 the opportunity has been taken to make certain changes in the text of such articles. Miss Hill, by her knowledge and love of nature, is remark ably well fitted to describe the Flora and Fauna. The hills and valleys of the town, with all their shrubbery and other vegetation, and the brooks and meadows with their moats and swamps, are well-known to· her ; and the varioµs animals that live on the land or in the-water are equally familiar. The birds even seem to know that she is a lover of their species, and they are always ready to answer her calls when she imi-, tates their notes. As a labor of love on her part, she has written this description, and, by her courtesy and kindness in the matter, she has placed me un_der special obligation~. -

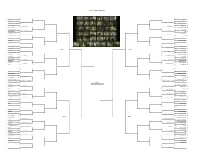

Favorite Twilight Zone Episodes.Xlsx

TITLE - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes 1 Time Enough at Last 57 56 Eye of the Beholder 1 Time Enough at Last Eye of the Beholder 32 The Fever 4 5 The Mighty Casey 32 16 A World of Difference 25 19 The Rip Van Winkle Caper 16 I Shot an Arrow into the Air A Most Unusual Camera 17 I Shot an Arrow into the Air 35 41 A Most Unusual Camera 17 8 Third from the Sun 44 37 The Howling Man 8 Third from the Sun The Howling Man 25 A Passage for Trumpet 16 Nervous22 Man in a Four Dollar Room 25 9 Love Live Walter Jameson 34 45 The Invaders 9 Love Live Walter Jameson The Invaders 24 The Purple Testament 25 13 Dust 24 5 The Hitch-Hiker 52 41 The After Hours 5 The Hitch-Hiker The After Hours 28 The Four of Us Are Dying 8 19 Mr. Bevis 28 12 What You Need 40 31 A World of His Own 12 What You Need A World of His Own 21 Escape Clause 19 28 The Lateness of the Hour 21 4 And When the Sky Was Opened 37 48 The Silence 4 And When the Sky Was Opened The Silence 29 The Chaser 21 11 The Mind and the Matter 29 13 A Nice Place to Visit 35 35 The Night of the Meek 13 A Nice Place to Visit The Night of the Meek 20 Perchance to Dream 24 24 The Man in the Bottle 20 Season 1 Season 2 6 Walking Distance 37 43 Nick of Time 6 Walking Distance Nick of Time 27 Mr. -

![The National Melodist. [A Collection of Songs.] First](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1064/the-national-melodist-a-collection-of-songs-first-3851064.webp)

The National Melodist. [A Collection of Songs.] First

THE GLEN COLLECTION OF SCOTTISH MUSIC Presented by Lady Dorothea Ruggles- Brise to the National Library of Scotland, in memory of her brother, Major Lord George Stewart Murray, Black Watch, killed in action in France in 1914. 28th January 1927. : THE NATIONAL MELODIST, #cv^t ^«vie&. "Sing away, sing away by day and by night, " — Fashionable ballad. EDiNBURGH PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY IF. GLASS, 44, SOUTH BRIDGE, AND SOLD BY ALL THE BOOKSELLERS. MDCCOXXXVir. Digitized by tine Internet Arcliive in 2011 witli funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/nationalmelodi.stOOmelo ADVERTISEMENT. An actor on his benefii night is usually compelled at the fall of the curtain to return thanks to his audience for their liberality, — in like manner do we, on the termination of this, our first volume, sponta- neously appear before the tribunal of our numerous subscribers and correspondents for the same pur- pose. Among ouf correspondents we do not class original conti'ibutors, for the}", we take it, are more obliged to us than we to them. We would be very glad, by the way, if they could send better things than they usually favour us with. The most of those which we have yet received are a hetei'ogenous mass of words, and it often astonishes us how people contrive to write such nonsense, for we had thought it next to impossible. We did not knovv,—as certainly we should have done—that the effusion entitled " Bon. nie Lizzie," is the production of Mr Robert Gilfillan. It was sent to us anonymously, and he may I'est as- sured that our admiration of his poetical powers did not in any way influence us in discarding two stanzas of it as execrable rubbish. -

The Life of James Flanagan

. E^'P^B Hiv^ * ^^^^BB ^r ^ ^H 1 A-^2^ ^j KKSMb M v\ ^9^^H: fc 1 . k iJ^l ?|s BLedBML fl FT Km. II \ m I 1 i\ 1 ^^B& t» -. H \ K*"^- > ML* \yf S ^^HH_ J 1 ! i. , Ii j £ " "^/zafa 2>_y -KZ/Jott # J-^i/- ~J: >^u*-<jS i Aa^t^i T THE LIFE OF JAMES FLANAGAN PREACHER, EVANGELIST, AUTHOR. BY R. W. RUSSELL. HOLBORN PUBLISHING HOUSE, HOLBORN HALL, CLERKENWELL ROAD, E.C.I. TABLE OF PRINCIPAL DATES 1851. Born in Mansfield, December 18th. 1872. Converted in Bath Street Chapel, Mansfield. 1874. Became a Local Preacher. 1883. First Mission at Long Clawson. 1884. Appointed Evangelist at Melton Mowbray. 1885. Appointed City Missioner at Nottingham. 1887. Appointed Superintendent of Albert Hall Mission, Nottingham. 1 89 1. Entered the Ministry of the Primitive Methodist Church. Appointed to Trinity Street Chapel, Southwark, London. 1900. Opening of St. George's Hall, January 4th. 1902. Engaged to raise Funds for purchase of Freehold. 1905. Advocate of Home Missions. 1906. First Visit to New Zealand and Australia. 1909. Appointed Pastor of Canaan Church, Nottingham. 191 1. Death of Mrs. Flanagan, January 24th. 19 1 3. Second Visit to New Zealand. 19 14. Visit to South Africa. Superannuated 19 1 8. Died at Nottingham, March 30th. Buried April 4th. 1919. Unveiling of Memorial Tablet at St. George's Hall, November 12th. preface This brief biography of the Rev. James Flanagan has been written in response to the request of the representatives of his family and in the hope that its publication may promote the work of evangelism in the Churches. -

Rod Serling Papers, 1945-1969

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5489n8zx No online items Finding Aid for the Rod Serling papers, 1945-1969 Finding aid prepared by Processed by Simone Fujita in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Kelley Wolfe Bachli, 2010. Prior processing by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Rod Serling 1035 1 papers, 1945-1969 Descriptive Summary Title: Rod Serling papers Date (inclusive): 1945-1969 Collection number: 1035 Creator: Serling, Rod, 1924- Extent: 23 boxes (11.5 linear ft.) Abstract: Rodman Edward Serling (1924-1975) wrote teleplays, screenplays, and many of the scripts for The Twilight Zone (1959-65). He also won 6 Emmy awards. The collection consists of scripts for films and television, including scripts for Serling's television program, The Twilight Zone. Also includes correspondence and business records primarily from 1966-1968. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. -

Twlight Zone Episode Guide

a Ed Wynn in One For The Angels EPISODE GUIDE ESCAPE CLAUSE JUDGMENT NIGHT Writer: Rod Serling. Director: Mitch Leisen. Cast: Writer: Rod Serling. Director: John Brahm. Cast: Compiled by GARY GERANI, David Wayne, Virginia Christine, Wendell Holmes, Nehemiah Persoff, Ben Wright, Patrick McNee, Bradley Deirdre Owen, author of Fantastic Television Thomas Gomez. Hugh Sanders, Leslie James Franciscus. A hypochondriac makes a pact with the Devil Murky tale about a passenger aboard a war- for immortality. He then kills someone for First Season: 1959-60 time freighter who is certain the ship will be kicks, but instead of getting the electric chair, sunk at 1:15A.M. he is sentenced to life imprisonment! WHERE IS EVERYBODY? Writer: Rod Serling. Director: Robert Stevens. AND WHEN THE SKY WAS Cast: Earl Holliman, James Gregory. THE LONELY Writer: Rod Serling. Director: Jack Smight. Cast: Pilot show for the series concerns a man who OPENED Jack Warden, Jean Marsh, John Dehner, Ted Writer: Rod Serling. Director: Douglas Heyes. finds himself in a completely deserted city. In Knight, JimTurley. Cast: Rod Taylor, Charles Aidman, James Hutton, the end, we learn that it was all a test to ob- This classic episode concerns one James Maxine Cooper. serve how human beings will respond to ex- Corry (Warden), a man convicted of murder After three astronauts return from man's first treme loneliness during space flights. This and sentenced to spend forty years on a dis- space flight, each of them mysteriously dis- was the only episode shot at Universal tant asteroid. He has only one companion— appears. -

![[Excerpts from Letters to Mrs. Jeanne Carr.] John Muir](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4998/excerpts-from-letters-to-mrs-jeanne-carr-john-muir-9294998.webp)

[Excerpts from Letters to Mrs. Jeanne Carr.] John Muir

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes John Muir Papers 1-1-1905 [Excerpts from Letters to Mrs. Jeanne Carr.] John Muir Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmb Recommended Citation Muir, John, "[Excerpts from Letters to Mrs. Jeanne Carr.]" (1905). John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes. 289. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/jmb/289 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the John Muir Papers at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in John Muir: A Reading Bibliography by Kimes by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. , JOHN MUIR': GEOLOGIST, EXPLORER, NATURALIST -~ • And Nature, .the .old nurse, took And he wandered away and away The child upon her knee, · With Nature, the dear old nurse, Saying: · "Here is a story-book Who sang to him night and day . ' . Thy Father has written for thee;'' The rh,Ymes of the universe- - ... 11 "Come wander with me, she said;· And whenev~r the way seemed long, Into· regions yet untrod; ' . .Or his heart began to fail, And read what is still unread She would sing a more wonderful song, 11 In the manuscripts of God. · Or tell a more marveious tale. E words so long ago applied by Longfellow to the elder Agassiz, have an equal descriptive power when attached I1Dt:iili~l4 ·t:o the lonely student of the A~ericari glaciers. · They are,· perhaps, even truer of the Scotch-American, than ~ ·~;:~aru of the Swiss, since the latter, although a pioneer in his II chosen path of scientific progress, lived. -

TZ-Original-Brackets

TITLE - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes 1 Time Enough at Last Eye of the Beholder 1 32 The Fever The Mighty Casey 32 16 A World of Difference The Rip Van Winkle Caper 16 17 I Shot an Arrow into the Air A Most Unusual Camera 17 8 Third from the Sun The Howling Man 8 25 A Passage for Trumpet Nervous Man in a Four Dollar Room 25 9 Love Live Walter Jameson The Invaders 9 24 The Purple Testament Dust 24 5 The Hitch-Hiker The After Hours 5 28 The Four of Us Are Dying Mr. Bevis 28 12 What You Need A World of His Own 12 21 Escape Clause The Lateness of the Hour 21 4 And When the Sky Was Opened The Silence 4 29 The Chaser The Mind and the Matter 29 13 A Nice Place to Visit The Night of the Meek 13 20 Perchance to Dream The Man in the Bottle 20 Season 1 Season 2 6 Walking Distance Nick of Time 6 27 Mr. Denton on Doomsday Static 27 11 The Last Flight A Penny for Your Thoughts 11 22 Judgment Night The Prime Mover 22 3 A Stop at Willoughby The Obsolete Man 3 30 The Big Tall Wish A Thing about Machines 30 14 Mirror Image The Odyssey of Flight 33 14 19 Elegy Long Distance Call 19 7 People Are Alike All Over Shadow Play 7 26 Execution Mr. -

Twilight Zone

7/2/2019 Twilight Zone - Rod Serling Edition Trading Cards Checklist Twilight Zone - Rod Serling Edition Trading Cards Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 001 Where Is Everybody? [ ] 002 One For The Angels [ ] 003 Mr. Denton on Doomsday [ ] 004 The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine [ ] 005 Walking Distance [ ] 006 Escape Clause [ ] 007 The Lonely [ ] 008 Time Enough At Last [ ] 009 Perchance To Dream [ ] 010 Judgment Night [ ] 011 And When The Sky Was Opened [ ] 012 What You Need [ ] 013 The Four Of Us Are Dying [ ] 014 Third From The Sun [ ] 015 I Shot An Arrow Into The Air [ ] 016 The Hitch-Hiker [ ] 017 The Fever [ ] 018 The Last Flight [ ] 019 The Purple Testament [ ] 020 Elegy [ ] 021 Mirror Image [ ] 022 The Monsters Are Due On Maple Street [ ] 023 A World Of Difference [ ] 024 Long Live Walter Jameson [ ] 025 People Are Alike All Over [ ] 026 Execution [ ] 027 The Big Tall Wish [ ] 028 A Nice Place To Visit [ ] 029 Nightmare As A Child [ ] 030 A Stop At Willoughby [ ] 031 The Chaser [ ] 032 A Passage For Trumpet [ ] 033 Mr. Bevis [ ] 034 The After Hours [ ] 035 The Mighty Casey [ ] 036 A World Of His Own [ ] 037 King Nine Will Not Return [ ] 038 The Man In The Bottle [ ] 039 Nervous Man In A Four Dollar Room [ ] 040 A Thing About Machines https://www.scifihobby.com/products/printablechecklist.cfm?SetID=358 1/8 7/2/2019 Twilight Zone - Rod Serling Edition Trading Cards Checklist [ ] 041 The Howling Man [ ] 042 Eye Of The Beholder [ ] 043 Nick of Time [ ] 044 The Lateness Of The Hour [ ] 045 The Trouble With Templeton [ ] 046 A Most Unusual Camera [ ] 047 The Night of the Meek [ ] 048 Dust [ ] 049 Back There [ ] 050 The Whole Truth [ ] 051 The Invaders [ ] 052 A Penny For Your Thoughts [ ] 053 Twenty-Two [ ] 054 The Odyssey Of Flight 33 [ ] 055 Mr. -

Favorite Twilight Zone Episodes.Xlsx

TITLE - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Third Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Third Round Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes 1 Time Enough at Last 57 56 Eye of the Beholder 1 Time Enough at Last 52 40 Eye of the Beholder 32 The Fever 4 5 The Mighty Casey 32 Time Enough at Last 81 72 Eye of the Beholder 16 A World of Difference 25 19 The Rip Van Winkle Caper 16 I Shot an Arrow into the Air 9 21 A Most Unusual Camera 17 I Shot an Arrow into the Air 35 41 A Most Unusual Camera 17 Time Enough at Last 77 71 Eye of the Beholder 8 Third from the Sun 44 37 The Howling Man 8 Third from the Sun 41 31 The Howling Man 25 A Passage for Trumpet 16 Nervous22 Man in a Four Dollar Room 25 Third from the Sun 23 33 The Howling Man 9 Love Live Walter Jameson 34 45 The Invaders 9 Love Live Walter Jameson 20 30 The Invaders 24 The Purple Testament 25 13 Dust 24 Time Enough at Last 82 66 Eye of the Beholder 5 The Hitch-Hiker 52 41 The After Hours 5 The Hitch-Hiker 45 35 The After Hours 28 The Four of Us Are Dying 8 19 Mr. Bevis 28 The Hitch-Hiker 70 69 The After Hours 12 What You Need 40 31 A World of His Own 12 What You Need 15 24 A World of His Own 21 Escape Clause 19 28 The Lateness of the Hour 21 The Hitch-Hiker 41 46 The After Hours 4 And When the Sky Was Opened 37 48 The Silence 4 And When the Sky Was Opened 30 30 The Silence 29 The Chaser 21 11 The Mind and the Matter 29 A Nice Place to Visit 32 32 The Night of the Meek 13 A Nice Place to Visit 35 35 The Night of the Meek 13 A Nice Place to Visit 31 31 The Night of the Meek 20 Perchance to Dream 24 24 The Man in the Bottle 20 Season 1 Time Enough at Last Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?Season 2 6 Walking Distance 37 43 Nick of Time 6 Walking Distance 38 36 Nick of Time 27 Mr.