Wu Tiecheng in the 1911 Revolution in Jiujiang, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating China's Fossil-Fuel CO2 Emissions from A

Evaluating China's fossil-fuel CO2 emissions from a comprehensive dataset of nine inventories Pengfei Han1*, Ning Zeng2*, Tom Oda3, Xiaohui Lin4, Monica Crippa5, Dabo Guan6,7, Greet Janssens-Maenhout5, Xiaolin Ma8, Zhu Liu6,9, Yuli Shan10, Shu Tao11, Haikun Wang8, Rong Wang11,12, 5 Lin Wu4 , Xiao Yun11, Qiang Zhang13, Fang Zhao14, Bo Zheng15 1State Key Laboratory of Numerical Modeling for Atmospheric Sciences and Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 2Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Science, and Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA 10 3Goddard Earth Sciences Research and Technology, Universities Space Research Association, Columbia, MD, United States 4State Key Laboratory of Atmospheric Boundary Layer Physics and Atmospheric Chemistry, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 5European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), Directorate for Energy, Transport and Climate, Air and Climate Unit, Ispra (VA), Italy 15 6Department of Earth System Science, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China 7Water Security Research Centre, School of International Development, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK 8State Key Laboratory of Pollution Control and Resource Reuse, School of the Environment, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China 9Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, School of International Development, University of East Anglia, Norwich, 20 UK 10Energy and Sustainability -

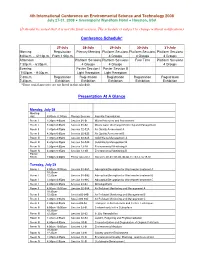

Preliminary Presentation Schedule

4th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology 2008 July 27-31, 2008 Greenspoint Wyndham Hotel Houston, USA (It should be noted that it is not the final version. The schedule is subject to change without notification) Conference Schedule* 27-July 28-July 29-July 30-July 31-July Morning Registration Plenary Meeting Platform Sessions Platform Sessions Platform Sessions 8:00a.m. - 12:10p.m. From 1:00p.m. 4 Groups 4 Groups 4 Groups Afternoon Platform Sessions Platform Sessions Free Time Platform Sessions 1:30p.m. - 6:05p.m. 4 Groups 4 Groups 4 Groups Evening Poster Session I Poster Session II 7:00p.m. - 9:00p.m. Light Reception Light Reception 7:30a.m. - Registration Registration Registration Registration Registration 7:30p.m. Exhibition Exhibition Exhibition Exhibition Exhibition *Some social activities are not listed in this schedule. Presentation At A Glance Monday, July 28 Meeting Hall 9:00am-11:50am Plenary Session Keynote Presentation Room I 1:30pm-4:05pm Session 01-01 Water Resouces and Assessment Room I 4:30pm-6:05pm Session 01-02 Waste water Discharge Monitoring and Management Room II 1:30pm-4:05pm Session 02-02A Air Quality Assessment A Room II 4:30pm-6:05pm Session 02-02B Air Quality Assessment B Room III 1:30pm-4:05pm Session 03-03A Solid Waste Management A Room III 4:30pm-6:05pm Session 03-03B Solid Waste Management B Room IV 1:30pm-4:05pm Session 13-2A Environmental Monitoring A Room IV 4:30pm-6:05pm Session 13-2B Environmental Monitoring B Poster Room 7:00pm-9:00pm Poster Session I Sessions 01-01~01-05, -

Advances in Geophysical Methods Used for Uranium Exploration and Their Applications in China

ADVANCES IN GEOPHYSICAL METHODS USED FOR URANIUM EXPLORATION AND THEIR APPLICATIONS IN CHINA J. DENG, H. CHEN, Y. WANG, H. LI, H. YANG, Z. ZHANG East China University of Technology, Nanchang, China 1. INTRODUCTION Geophysics is one of the most useful techniques for uranium exploration. It supports the development of geological models through the definition of lithological, structural and alteration characteristics of metallogenic environments under evaluation. With exploration at increasing depths, the traditional radiometric method is no longer effective for uranium exploration. Uranium mineralization is not closely related with observable gravity, magnetic and impedance anomalies. Gravity, magnetic and electromagnetic techniques can be used to survey the subsurface geological background of an area and can be efficient in detecting deeper uranium deposits [1]. The progression and development of geophysical methods, measurement techniques, data processing, computer modelling and inversion have permitted improvements in the field of uranium exploration [1, 2]. It is well known that progress in geophysical methods has contributed to successful field investigations in the exploration for deeper deposits (including uranium). Xu et al. [2] have reviewed the latest advances and developing trends in geophysical and geochemical methods and techniques applied to uranium resources exploration in China [2]. Following this work, this paper summarizes the research carried out by the East China University of Technology during the past decade. This includes 3-D inversion of magnetic data and 3-D electromagnetic methods tested in the Xiazhuang area over granite type uranium deposits [3, 4] and in the Xiangshan area over volcanic type uranium deposits [5]. Results indicate that some of the objectives, including mapping of basement structures, rock interface and lithology recognition, can be achieved. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Across the Geo-political Landscape Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political Networks in the Wartime Era 1937-1949 Guo, Xiangwei Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Across the Geo-political Landscape: Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political -

Biol. Pharm. Bull. 34(7): 1072-1077 (2011)

1072 Regular Article Biol. Pharm. Bull. 34(7) 1072—1077 (2011) Vol. 34, No. 7 Rb1 Protects Endothelial Cells from Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Cell Senescence by Modulating Redox Status a b a a a a a Ding-Hui LIU, Yan-Ming CHEN, Yong LIU, Bao-Shun HAO, Bin ZHOU, Lin WU, Min WANG, a c ,a,c Lin CHEN, Wei-Kang WU, and Xiao-Xian QIAN* a Department of Cardiology, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University; b Department of Endocrinology, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University; Guangzhou, Guangdong 510630, China: and c Institute Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Sun Yat-sen University; Guangzhou, Guangdong 510630, China. Received February 12, 2011; accepted April 12, 2011; published online April 15, 2011 Senescence of endothelial cells has been proposed to play an important role in endothelial dysfunction and atherogenesis. In the present study we aimed to investigate whether ginsenoside Rb1, a major constituent of gin- seng, protects endothelial cells from H2O2-induced endothelial senescence. While H2O2 induced premature senes- cent-like phenotype of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), as judged by increased senescence- associated b-galactosidase (SA-b-gal) activity, enlarged, flattened cell morphology and sustained growth arrest, our results demonstrated that Rb1 protected endothelial cells from oxidative stress induced senescence. Mechan- istically, we found that Rb1 could markedly increase intracellular superoxide dismutase (Cu/Zn SOD/SOD1) activity and decrease the malondialdehyde (MDA) level in H2O2-treated HUVECs, and suppress the generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). Consistent with these findings, Rb1 could effectively restore the protein expression of Cu/Zn SOD, which was down-regulated in H2O2 treated cells. -

Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture

In &a r*tm Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture edited by Sucheng Chan Exclusion and the Chinese Communify in America, r88z-ry43 Edited by Sucheng Chan Also in the series: Gary Y. Okihiro, Cane Fires: The Anti-lapanese Moaement Temple University press in Hawaii, t855-ry45 Philadelphia Chapter 6 The Kuomintang in Chinese American Kuomintang in Chinese American Communities 477 E Communities before World War II the party in the Chinese American communities as they reflected events and changes in the party's ideology in China. The Chinese during the Exclusion Era The Chinese became victims of American racism after they arrived in Him Lai Mark California in large numbers during the mid nineteenth century. Even while their labor was exploited for developing the resources of the West, they were targets of discriminatory legislation, physical attacks, and mob violence. Assigned the role of scapegoats, they were blamed for society's multitude of social and economic ills. A populist anti-Chinese movement ultimately pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the first Chinese exclusion act in 1882. Racial discrimination, however, was not limited to incoming immi- grants. The established Chinese community itself came under attack as The Chinese settled in California in the mid nineteenth white America showed by words and deeds that it considered the Chinese century and quickly became an important component in the pariahs. Attacked by demagogues and opportunistic politicians at will, state's economy. However, they also encountered anti- Chinese were victimizedby criminal elements as well. They were even- Chinese sentiments, which culminated in the enactment of tually squeezed out of practically all but the most menial occupations in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. -

The Conceptual Planning for the Development of Tourism Resources in Ruichang City Based on the Transformation of Tourism Industry

Landscape and Urban Horticulture (2018) Vol. 1: 1-7 Clausius Scientific Press, Canada The Conceptual Planning for the Development of Tourism Resources in Ruichang City Based on the Transformation of Tourism Industry Liu Wentaoa, Xiao Xuejianb College of Landscape and Art, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, 201805, China E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: Tourism industry, Transformation, Tourism resources, Conceptual planning Abstract: With the international and domestic tourism industry continuing to heat up, the number of tourists sustainable growth, and the social environment changing, the economy increasing, people experience fundamental changes in their expectations, purposes and modes of travel. Self-help travel is the mainstay. Self-help and group travel complement each other. As the important part of the tertiary industry, tourism has played an essential role in the development of local economy and increasing of employment rate. Original article, Published date: 2018-05-11 DOI: 10.23977/lsuh.2018.11001 ISSN: 523-6415 https://www.clausiuspress.com/journal/LSUH.html 1. The outlook of tourism Premier Li Keqiang pointed out that “tourism do not just represent service industry or consumer industry. It is a composite of all the industry”. 1.1 Macro Background of Tourism Development Chinese authority takes the tourism industry as the main body of tertiary industry, to form a comprehensive industry in which the first, second and third industries participate. Tourism industry make the incomparable economy value, which can launch fresh impetus, promote the development of related industries, stimulate GDP, and increase the number of employment in the current stage of our industry which lack of innovation capacity and cultural product. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Hobsbawm 1990, 66. 2. Diamond 1998, 322–33. 3. Fairbank 1992, 44–45. 4. Fei Xiaotong 1989, 1–2. 5. Diamond 1998, 323, original emphasis. 6. Crossley 1999; Di Cosmo 1998; Purdue 2005a; Lavely and Wong 1998, 717. 7. Richards 2003, 112–47; Lattimore 1937; Pan Chia-lin and Taeuber 1952. 8. My usage of the term “geo-body” follows Thongchai 1994. 9. B. Anderson 1991, 86. 10. Purdue 2001, 304. 11. Dreyer 2006, 279–80; Fei Xiaotong 1981, 23–25. 12. Jiang Ping 1994, 16. 13. Morris-Suzuki 1998, 4; Duara 2003; Handler 1988, 6–9. 14. Duara 1995; Duara 2003. 15. Turner 1962, 3. 16. Adelman and Aron 1999, 816. 17. M. Anderson 1996, 4, Anderson’s italics. 18. Fitzgerald 1996a: 136. 19. Ibid., 107. 20. Tsu Jing 2005. 21. R. Wong 2006, 95. 22. Chatterjee (1986) was the first to theorize colonial nationalism as a “derivative discourse” of Western Orientalism. 23. Gladney 1994, 92–95; Harrell 1995a; Schein 2000. 24. Fei Xiaotong 1989, 1. 25. Cohen 1991, 114–25; Schwarcz 1986; Tu Wei-ming 1994. 26. Harrison 2000, 240–43, 83–85; Harrison 2001. 27. Harrison 2000, 83–85; Cohen 1991, 126. 186 • Notes 28. Duara 2003, 9–40. 29. See, for example, Lattimore 1940 and 1962; Forbes 1986; Goldstein 1989; Benson 1990; Lipman 1998; Millward 1998; Purdue 2005a; Mitter 2000; Atwood 2002; Tighe 2005; Reardon-Anderson 2005; Giersch 2006; Crossley, Siu, and Sutton 2006; Gladney 1991, 1994, and 1996; Harrell 1995a and 2001; Brown 1996 and 2004; Cheung Siu-woo 1995 and 2003; Schein 2000; Kulp 2000; Bulag 2002 and 2006; Rossabi 2004. -

Shanxi Takes Stock of Past Achievements

12 | DISCOVER SHANXI Friday, January 29, 2021 CHINA DAILY Shanxi takes stock of past achievements Provincial congress hails success in poverty alleviation, plans economic transformation By YUAN SHENGGAO To make the transformation pos sible, Shanxi has developed 62 new he past five years, the 13th comprehensive transformation FiveYear Plan (201620), demonstration zones in the past was a crucial period for five years. This compares with just Shanxi province to develop 26 such zones in earlier years. Tan allaround xiaokang, or moder The combined area of the 88 ately prosperous, society, said Lin demonstration zones is 2,881 Wu, governor of Shanxi, at the square kilometers, or 1.85 percent recent session of the provincial peo of Shanxi’s total land area. The ple’s congress. industrial added value of these The fourth session of 13th Shanxi zones took up 35 percent of the pro People’s Congress was held in the vincial total. provincial capital of Taiyuan from Lin said Shanxi regards techno Jan 2023. logical innovation as a major driver The provincial legislature, the for local growth. Five key national Shanxi People’s Congress, with 517 laboratories and 31 corporate tech delegates present at the session, nological centers were established endorsed the work report of the in Shanxi over the past five years. provincial government, the prov The number of certificated high ince’s 14th FiveYear Plan (202125) tech enterprises in 2020 was more and the longrange objectives for than 3.5 times that of 2015. the period ending in 2035, as well as The governor said the province new local regulations. -

Inventing Chinese Buddhas: Identity, Authority, and Liberation in Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism

Inventing Chinese Buddhas: Identity, Authority, and Liberation in Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism Kevin Buckelew Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Kevin Buckelew All rights reserved Abstract Inventing Chinese Buddhas: Identity, Authority, and Liberation in Song-Dynasty Chan Buddhism Kevin Buckelew This dissertation explores how Chan Buddhists made the unprecedented claim to a level of religious authority on par with the historical Buddha Śākyamuni and, in the process, invented what it means to be a buddha in China. This claim helped propel the Chan tradition to dominance of elite monastic Buddhism during the Song dynasty (960–1279), licensed an outpouring of Chan literature treated as equivalent to scripture, and changed the way Chinese Buddhists understood their own capacity for religious authority in relation to the historical Buddha and the Indian homeland of Buddhism. But the claim itself was fraught with complication. After all, according to canonical Buddhist scriptures, the Buddha was easily recognizable by the “marks of the great man” that adorned his body, while the same could not be said for Chan masters in the Song. What, then, distinguished Chan masters from everyone else? What authorized their elite status and granted them the authority of buddhas? According to what normative ideals did Chan aspirants pursue liberation, and by what standards did Chan masters evaluate their students to determine who was worthy of admission into an elite Chan lineage? How, in short, could one recognize a buddha in Song-dynasty China? The Chan tradition never answered this question once and for all; instead, the question broadly animated Chan rituals, institutional norms, literary practices, and visual cultures. -

Chinese “Guanxi”: Does It Actually Matter?

Asian Journal of Management Sciences & Education Vol. 8(1) January 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CHINESE “GUANXI”: DOES IT ACTUALLY MATTER? Md. Bashir Uddin Khan 1, Yanwen Tang 2 1Researcher, Department of Sociology, School of Sociology and Political Science, Shanghai University, CHINA and Assistant Professor, Department of Criminology and Police Science, Mawlana Bhashani Science and Technology University, Santosh, Tangail, BANGLADESH; 2Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, School of Sociology and Political Science, Shanghai University, Shanghai, CHINA. [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Guanxi, which evolved out of the Chinese social philosophy of Confucianism, is treated as one of the inevitable issues in the Chinese culture. The impact of guanxi starts from the family and ends up to the international trades and mutual agreements. This mutual and long-term reciprocity of exchanging some benefits often seems to be obscure to the foreigners, specially to the Westerners. Chinese social web is cemented by this strong phenomenon that is embedded in the Chinese people’s philosophical aspects. -

The Mishu Phenomenon: Patron-Client Ties and Coalition-Building Tactics

Li, China Leadership Monitor No.4 The Mishu Phenomenon: Patron-Client Ties and Coalition-Building Tactics Cheng Li China’s ongoing political succession has been filled with paradoxes. Jockeying for power among various factions has been fervent and protracted, but the power struggle has not led to a systemic crisis as it did during the reigns of Mao and Deng. While nepotism and favoritism in elite recruitment have become prevalent, educational credentials and technical expertise are also essential. Regional representation has gained importance in the selection of Central Committee members, but leaders who come from coastal regions will likely dominate the new Politburo. Regulations such as term limits and an age requirement for retirement have been implemented at various levels of the Chinese leadership, but these rules and norms will perhaps not restrain the power of Jiang Zemin, the 76-year-old “new paramount leader.” While the military’s influence on political succession has declined during the past decade, the Central Military Commission is still very powerful. Not surprisingly, these paradoxical developments have led students of Chinese politics to reach contrasting assessments of the nature of this political succession, the competence of the new leadership, and the implications of these factors for China’s future. This diversity of views is particularly evident regarding the ubiquitous role of mishu in the Chinese leadership. The term mishu, which literally means “secretary” in Chinese, refers to a range of people who differ significantly from each other in terms of the functions they fulfill, the leadership bodies they serve, and the responsibilities given to them.