Lietuvos Muzikologija 17.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

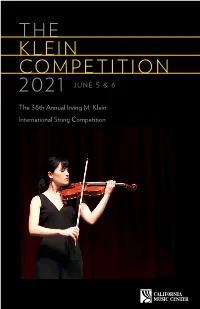

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Vi Saint Petersburg International New Music Festival Artistic Director: Mehdi Hosseini

VI SAINT PETERSBURG INTERNATIONAL NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: MEHDI HOSSEINI 21 — 25 MAY, 2019 facebook.com/remusik.org vk.com/remusikorg youtube.com/user/remusikorg twitter.com/remusikorg instagram.com/remusik_org SPONSORS & PARTNERS GENERAL PARTNERS 2019 INTERSECTIO A POIN OF POIN A The Organizing Committee would like to express its thanks and appreciation for the support and assistance provided by the following people: Eltje Aderhold, Karina Abramyan, Anna Arutyunova, Vladimir Begletsov, Alexander Beglov, Sylvie Bermann, Natalia Braginskaya, Denis Bystrov, Olga Chukova, Evgeniya Diamantidi, Valery Fokin, Valery Gergiev, Regina Glazunova, Andri Hardmeier, Alain Helou, Svetlana Ibatullina, Maria Karmanovskaya, Natalia Kopich, Roger Kull, Serguei Loukine, Anastasia Makarenko, Alice Meves, Jan Mierzwa, Tatiana Orlova, Ekaterina Puzankova, Yves Rossier, Tobias Roth Fhal, Olga Shevchuk, Yulia Starovoitova, Konstantin Sukhenko, Anton Tanonov, Hans Timbremont, Lyudmila Titova, Alexei Vasiliev, Alexander Voronko, Eva Zulkovska. 1 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall 4 Masterskaya M. K. Anikushina FESTIVAL CALENDAR Dekabristov St., 37 Vyazemsky Ln., 8 mariinsky.ru vk.com/sculptorstudio 2 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre 5 “Lumiere Hall” creative space TUESDAY / 21.05 19:00 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall Fontanka River Embankment 49, Lit A Obvodnogo Kanala emb., 74А ensemble für neue musik zürich (Switzerland) alexandrinsky.ru lumierehall.ru 3 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov 6 The Concert Hall “Jaani Kirik” Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Dekabristov St., 54A Glinka St., 2, Lit A jaanikirik.ru WEDNESDAY / 22.05 13:30 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov conservatory.ru Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Composer meet-and-greet: Katharina Rosenberger (Switzerland) 16:00 Lumiere Hall Marcus Weiss, Saxophone (Switzerland) Ensemble for New Music Tallinn (Estonia) 20:00 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre Around the Corner (Spain, Switzerland) 4 Vyazemsky Ln. -

Mieczyslaw Weinberg: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

MIECZYSLAW WEINBERG: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1939-45: Suite for small orchestra, op. 26 1940-67: Symphony No.9 “Everlasting Times” for narrator, chorus and orchestra, op. 93 1941: Symphonic Poem for orchestra, op.6 1942: Symphony No.1, op.10: 40 minutes + (Northern Flowers cd) 1945-46: Symphony No.2 for string orchestra, op.30: 32 minutes + (Olympia and Alto cds) 1945-48: Cello Concerto, op.43: 30 minutes + (several recordings) 1946-47: Festive Scenes for orchestra, op. 36 1947: Two Ballet Suites for orchestra, op.40 1948: Sinfonietta No.1, op.41: 22 minutes + (Chandos and Neos cds) Concertino for Violin and Orchestra, op.42 1949: Greetings Overture, op. 44 1949-50/59: Symphony No.3, op.45: 32 minutes + (Chandos cd) 1949: Rhapsody on Moldovian Themes for orchestra, op.47, No.1: 13 minutes + (Olympia, Chandos and Naxos cds) (or for Violin and Orchestra, op.47, No.3) Polish Tunes for orchestra, op.47, No.2 Serenada for orchestra, op.47, No.4 1951-53: Fantasia for Cello and Orchestra, op.52: 18 minutes + (Chandos and Russian Disc cds) 1952: Cantata “In the Homeland” for chorus and orchestra, op.51 1954-55/64: Ballet “The Golden Key”, op.55 (and Ballet Suites No.1, op.55A, No.2, No.55B, No.3, op.55 C-(all + Olympia cds) and No.4, op.55d- 17 minutes + (Chandos and Olympia cd)) 1957: Symphonic Poem “Morning-Red” for orchestra, op.60 1957/61: Symphony No.4 in A minor, op.61: 28 minutes + (Melodiya, Olympia and Chandos cds) 1958: Ballet “The Wild Chrysantheme”, op. -

CURRENT and PAST APPOINTMENTS Associate

Joan Titus [email protected] Short CV Page 1 CURRENT AND PAST APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Fall 2013–present Assistant Professor, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Fall 2007–Fall 2013 Lecturer, The Ohio State University, Winter, Spring, and Summer 2007 Graduate Teaching/Research Associate, The Ohio State University 1998–2005 Graduate Research and Administrative Associate, The Ohio State University 2002–2003 EDUCATION The Ohio State University, Ph.D. Musicology, December 2006 Dissertation title: Modernism, Socialist Realism, and Identity in the Early Film Music of Dmitry Shostakovich, 1929–1932 The Ohio State University, M.A. Musicology; secondary areas in Film Studies and Slavic Studies, 2002 Thesis title: Montage Shostakovich: Film, Popular Culture, and the Finale of the Piano Concerto No.1 The University of Arizona, B.A.M. Music History, Art History, Violin Perf., Magna Cum Laude, 1998 AWARDS AND HONORS 2017 Distinguished Mentor Award, Honors College, UNC Greensboro 2014 AMS 75 PAYS Publication Subvention for The Early Film Music of Dmitry Shostakovich, American Musicological Society 2008 Summer Excellence Award, UNC Greensboro 2008 Dobro Slovo, Russian Honor Society, UNC Greensboro 2007 Pi Kappa Lambda, The Ohio State University 2007 Peter A. Costanza Outstanding Dissertation Award, The Ohio State University 2005 Jack and Zoe Johnstone Graduate Award for Excellence in Musicology The Ohio State University 2005 Mary H. Osburn Memorial Graduate Fellowship Award, The Ohio State University 2004 Graduate Student Award in Musicology, The Ohio State University GRANTS & STIPENDS 2020– Provost’s Grant, Women’s Suffrage Centennial (“She Can We Can”), 2021 UNC Greensboro 2020 Kohler Grant for International Research (suspended because of COVID-19), UNC Greensboro 2019 Dean’s Initiative for Research (suspended because of COVID-19), UNC Greensboro. -

Violin, Viola, Cello

6144_Program 6/5/08 4:43 PM Page 1 The Board of the California Music Center would like to express our special thanks to Elizabeth Chamberlain a great friend of the Klein Competition. Her deep appreciation of music and young artists is an inspiration to all of us. 1 6144_Program 6/5/08 4:43 PM Page 2 The California Music Center and San Francisco State University present The Twenty-Third Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition June 11-15, 2008 with distinguished judges: Peter Gelfand Alan Grishman Marc Gottlieb Jennifer Kloetzel Patricia Taylor Lee Melvin Margolis Donna Mudge Alice Schoenfeld Franks Stemper First Prize: $10,000 The Irving M. Klein Memorial Award Second Prize: $5,000 The William M. Bloomfield Memorial Award Third Prize: $2,500 The Alice Anne Roberts Memorial Award Fourth Prizes: $1,500 The Thomas and Lavilla Barry Award The Jules and Lena Flock Memorial Award Additional underwriting provided by cgrafx, Inc., marketing & design Allen R. and Susan E. Weiss Memorial Prize: $200 For best performance of the commissioned work Each semifinalist not awarded a named prize will receive $1,000. 2 6144_Program 6/5/08 4:43 PM Page 3 In Memoriam Warren G. Weis 1922-1995 Warren G. Weis was a long-time supporter of the California Music Center and the Irving M. Klein International String Competition. He took great delight in music and his close association with musicians and teachers, and supported the aspirations of young musicians withs generosity and enthusiasm. Bill Bloomfield 1918-1998 A member of the Board of the Competition, Bill Bloomfield was an amateur musician and a lifelong supporter sand enthusiast of music and the arts. -

Chamber Symphony Chamber Symphony

Chamber Symphony Chamber Symphony Commission commissioned by the See Hear! Program of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts Premiere 19 May 2005 in Perelman Theater, Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, Philadelphia, PA by the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, Jeri Lynne Johnson, conductor Instrumentation flute (doubling piccolo) oboe clarinet in B-flat (doubling clarinet in E-flat) bassoon 2 horns in F trumpet in C trombone 3 violins 3 violas 3 violoncellos 2 contrabasses Duration approximately 20 minutes Copyright © 2005 by Jeremy Gill. All rights reserved. for my father Transposed Score J. Gill Chamber symphony (2005) q = 48 Flute doubling Piccolo non pp mf pp cresc. Oboe ppmf non pp cresc. Clarinet in B b doubling non Clarinet in E b pp mp pp cresc. Bassoon non pp mp pp cresc. Horn in F 1 pp mf Horn in F 2 pp mp Trumpet in C Trombone q = 48 3 Violins 1. 3 Violas 2.3. dal niente 3 Violoncellos dal niente 2 Contrabasses Copyright © 2005 by Jeremy Gill. All rights reserved. 2 8 , Fl. mf pp , Ob. mf pp , Cl. mf pp , Bsn mf pp , Hn 1 pp mf pp , Hn 2 pp mf pp div. a3 Vlns pp flautando 1. pp flautando Vlas 2.3. cresc. poco a p poco 1. p Vcs cresc. poco a poco 2.3. cresc. poco a poco p 3 15 Fl. pp mf f Ob. pp mf f Cl. pp f f Bsn pp f f Hn 1 pp mf Hn 2 pp f Vlns div. a3 1. mp Vlas 2.3. -

Listening Guide Chamber Symphony in F Major Op

Listening Guide Chamber Symphony in F major Op. 73a by Dimitri Shostakovich (arr. Barshai) This listening guide will explore the historical, cultural, and musical factors that make Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony in F major Op. 73a unique. After exploring this listening guide, you will have a better understanding of the musical features of this emotional work. Contents Description ........................................................................................................................................................ - 2 - Historical Context .......................................................................................................................................... - 2 - Listening Guide ................................................................................................................................................. - 4 - I. Allegretto (a fairly brisk speed) ............................................................................................................. - 4 - II. Moderato con moto (a moderate speed with motion) ........................................................................... - 5 - III. Allegro non troppo (fast and lively but not too fast) .............................................................................. - 6 - IV. Adagio (slow) ........................................................................................................................................ - 7 - V. Moderato (a moderate speed) ............................................................................................................. -

Msm String Chamber Orchestra

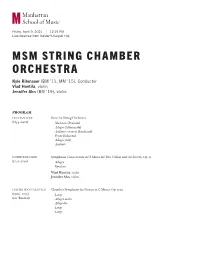

Friday, April 9, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA Kyle Ritenauer (BM ’11, MM ’15), Conductor Vlad Hontila, violin Jennifer Ahn (BM ’19), violin PROGRAM LEOS JANÁČEK Suite for String Orchestra (1854–1928) Moderato (Prelude) Adagio (Allemande) Andante con moto (Saraband) Presto (Scherzo) Adagio (Air) Andante JOSEPH BOLOGNE Symphonie Concertante in G Major for Two Violins and Orchestra, Op. 13 (1745–1799) Allegro Rondeau Vlad Hontila, violin Jennifer Ahn, violin DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a (1906–1975) Largo (arr. Barshai) Allegro molto Allegretto Largo Largo MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA VIOLIN 1 VIOLIN 2 VIOLA DOUBLE BASS HORN Corinne Au Selin Algoz Leah Glick Dylan Holly Emma Potter Short Hills, New Jersey Istanbul, Turkey Jerusalem, Israel Tucson, Arizona Surprise, Arizona Ally Cho Luxi Wang Dudley Raine Sophia Filippone Melbourne, Australia Sichuan, China Lynchburg, Virginia OBOE Glen Mills, Pennsylvania Messiah Ahmed Carolyn Carr Ellen O’Neill Dallas, Texas Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania CELLO New York, New York Edward Luengo Andres Ayola Miami, Florida New York, New York Pedro Bonet Madrid, Spain Students in this performance are supported by the L. John Twiford Music Scholarship, and the Herbert R. and Evelyn Axelrod Scholarship. We are grateful to the generous donors who made these scholarships possible. For information on establishing a named scholarship at Manhattan School of Music, please contact Susan Madden, Vice President for Advancement, at 917-493-4115 or [email protected]. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Kyle Ritenauer, Conductor Acclaimed New York-based conductor Kyle Ritenauer is establishing himself as one of classical and contemporary music’s singular artistic leaders. -

Curriculum Vitae LEON BOTSTEIN Personal Born

Curriculum Vitae LEON BOTSTEIN Personal Born: December 14, 1946, in Zurich, Switzerland Citizenship: United States of America Education Ph.D., M.A., History, Harvard University, 1985, 1968 B.A., History with special honors, The University of Chicago, 1967 The High School of Music and Art, New York City, 1963 Academic Appointments President, Bard College and Leon Levy Professor in the Arts and Humanities, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, 1975 to present President, Bard College at Simon's Rock, Great Barrington, Massachusetts, 1979 to present Editor, The Musical Quarterly, 1992 to present Visiting Professor, Lehrkanzel für Kultur und Geistesgeschichte, Hochschule für angewandte Kunst, Vienna, Spring 1988 Visiting Faculty, Manhattan School of Music, New York City, 1986 President, Franconia College, Franconia, New Hampshire, 1970–1975 Special Assistant to the President of the Board of Education of the City of New York, 1969–70 Lecturer, Department of History, Boston University, 1969 Non-Resident Tutor, Winthrop House, and Teaching Fellow, General Education, Harvard University, 1968-69 Music Appointments Music Director and Principal Conductor, The American Symphony Orchestra, New York City, 1992 to present Conductor Laureate, The Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra/Israel Broadcast Authority, Jerusalem, Israel. Music Director and Principal Conductor, 2003 to 2010. Conductor Laureate 2011 to present. Founder, Co-Artistic Director, The Bard Music Festival, 1990 to present Artistic Director, The American Russian Young Artists Orchestra, New York City, -

Marina Frolova-Walker from Modernism to Socialist

Marina Frolova-Walker From modernism to socialist... Marina Frolova-Walker FROM MODERNISM TO SOCIALIST REALISM IN FOUR YEARS: MYASKOVSKY AND ASAFYEV Abstract: Two outstanding personalities of the Soviet musical life in the 1920’s, the composer Nikolay Myaskovsky and the musicologist Boris Asafyev, both exponents of modernism, made volte-faces towards traditionalism at the beginning of the next decade. Myaskovsky’s Symphony no. 12 (1931) and Asafyev’s ballet The Flames of Paris (1932) became models for Socialist Realism in music. The letters exchanged between the two men testify to the former’s uneasiniess at the great success of those of his works he considered not valuable enough, whereas the latter was quite satisfied with his new career as composer. The examples of Myaskovsky and Asafyev show that early Soviet modernists made their move away from avantgarde creativity well before they faced any real danger from the bureacracy. Key-Words: Socialist Realism, Nikolay Myaskovsky, Boris Asafyev From 1929 to 1932, Stalin’s shock-workers were fuelled by the slogan, "Fulfil the Five-Year Plan in four years!" The years of foreign invasions and White reaction had devastated Russia’s economy; now from a base of almost nothing, Stalin set out to transform the Soviet Union into a new industrial great power. Alongside industrialization and collectivisation, the field of culture also underwent a transformation, from the pluralistic ferment of experimentation of the post-revolutionary decade to the semi-desert of Socialist Realism. First the self-proclaimed "proletarian" cultural organisations were used to bludgeon other groups out of existence. Then the same proletarian organisations were themselves dissolved in favour of state unions of writers, painters and com- posers. -

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich)

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich) (b Sontsovka, Bakhmutsk region, Yekaterinoslav district, Ukraine, 11/23 April 1891; d Moscow, 5 March 1953). Russian composer and pianist. He began his career as a composer while still a student, and so had a deep investment in Russian Romantic traditions – even if he was pushing those traditions to a point of exacerbation and caricature – before he began to encounter, and contribute to, various kinds of modernism in the second decade of the new century. Like many artists, he left his country directly after the October Revolution; he was the only composer to return, nearly 20 years later. His inner traditionalism, coupled with the neo-classicism he had helped invent, now made it possible for him to play a leading role in Soviet culture, to whose demands for political engagement, utility and simplicity he responded with prodigious creative energy. In his last years, however, official encouragement turned into persecution, and his musical voice understandably faltered. 1. Russia, 1891–1918. 2. USA, 1918–22. 3. Europe, 1922–36. 4. The USSR, 1936–53. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY DOROTHEA REDEPENNING © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online 1. Russia, 1891–1918. (i) Childhood and early works. (ii) Conservatory studies and first public appearances. (iii) The path to emigration. © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online Prokofiev, Sergey, §1: Russia: 1891–1918 (i) Childhood and early works. Prokofiev grew up in comfortable circumstances. His father Sergey Alekseyevich Prokofiev was an agronomist and managed the estate of Sontsovka, where he had gone to live in 1878 with his wife Mariya Zitkova, a well-educated woman with a feeling for the arts. -

July 4 Concert Launches Chamber Symphony Series

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 6-26-1974 July 4 concert launches Chamber Symphony series University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "July 4 concert launches Chamber Symphony series" (1974). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 23473. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/23473 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~news Information Services University of mon ana • missoula, montana 59801 • (406) 243-2522 FMMED IA TE LY dwyer, 243-4970 ~./26/74 local JULY 4 CONeERT LAUNCHES CHAHBER SYMPHONY SEJliES The MOntana Chamber Symphony opens its second concert season with a Fourth-of-July per- Eormance at 8 p. m. in the Music Recital Hall on the University of Montana campus. The con- ~ert is open to the public without charge. The 40-member orchestra, directed by Eugene Andrie, professor of music in the UM School of Fine Arts, will perform Moza~t's Sinphonie Concertant in E flat, with visiting professors hristopher Kimber, violinist, and Karin Pugh, violist, as soloists, and Faure's Elegie for polo Cello and Orchestra, with Florence Reynolds of the UM music faculty as soloist.