Download Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Read Or Download the Competition Program Guide

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2021 JUNE 5 & 6 The 36th Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition TABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors Dexter Lowry, President Katherine Cass, Vice President Lian Ophir, Treasurer Ruth Short, Secretary Susan Bates Richard Festinger Peter Gelfand 2 4 5 Kevin Jim Mitchell Sardou Klein Welcome The Visionary The Prizes Tessa Lark Stephanie Leung Marcy Straw, ex officio Lee-Lan Yip Board Emerita 6 7 8 Judith Preves Anderson The Judges/Judging The Mentor Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Competition Format Past Winners About California Music Center Marcy Straw, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director for the Klein Competition 12 18 22 californiamusiccenter.org [email protected] Artist Programs Artist Biographies Donor Appreciation 415.252.1122 On the cover: 21 25 violinist Gabrielle Després, First Prize winner 2020 In Memory Upcoming Performances On this page: cellist Jiaxun Yao, Second Prize winner 2020 WELCOME WELCOME Welcome to the 36th Annual This year’s distinguished jury includes: Charles Castleman (active violin Irving M. Klein International performer/pedagogue and professor at the University of Miami), Glenn String Competition! This is Dicterow (former New York Philharmonic concertmaster and faculty the second, and we hope the member at the USC Thornton School of Music), Karen Dreyfus (violist, last virtual Klein Competition Associate Professor at the USC Thornton School of Music and the weekend. We have every Manhattan School of Music), our composer, Sakari Dixon Vanderveer, expectation that next June Daniel Stewart (Music Director of the Santa Cruz Symphony and Wattis we will be back live, with Music Director of the San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra), Ian our devoted audience in Swensen (Chair of the Violin Faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory attendance, at the San of Music), and Barbara Day Turner (Music Director of the San José Francisco Conservatory. -

Mieczyslaw Weinberg: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

MIECZYSLAW WEINBERG: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1939-45: Suite for small orchestra, op. 26 1940-67: Symphony No.9 “Everlasting Times” for narrator, chorus and orchestra, op. 93 1941: Symphonic Poem for orchestra, op.6 1942: Symphony No.1, op.10: 40 minutes + (Northern Flowers cd) 1945-46: Symphony No.2 for string orchestra, op.30: 32 minutes + (Olympia and Alto cds) 1945-48: Cello Concerto, op.43: 30 minutes + (several recordings) 1946-47: Festive Scenes for orchestra, op. 36 1947: Two Ballet Suites for orchestra, op.40 1948: Sinfonietta No.1, op.41: 22 minutes + (Chandos and Neos cds) Concertino for Violin and Orchestra, op.42 1949: Greetings Overture, op. 44 1949-50/59: Symphony No.3, op.45: 32 minutes + (Chandos cd) 1949: Rhapsody on Moldovian Themes for orchestra, op.47, No.1: 13 minutes + (Olympia, Chandos and Naxos cds) (or for Violin and Orchestra, op.47, No.3) Polish Tunes for orchestra, op.47, No.2 Serenada for orchestra, op.47, No.4 1951-53: Fantasia for Cello and Orchestra, op.52: 18 minutes + (Chandos and Russian Disc cds) 1952: Cantata “In the Homeland” for chorus and orchestra, op.51 1954-55/64: Ballet “The Golden Key”, op.55 (and Ballet Suites No.1, op.55A, No.2, No.55B, No.3, op.55 C-(all + Olympia cds) and No.4, op.55d- 17 minutes + (Chandos and Olympia cd)) 1957: Symphonic Poem “Morning-Red” for orchestra, op.60 1957/61: Symphony No.4 in A minor, op.61: 28 minutes + (Melodiya, Olympia and Chandos cds) 1958: Ballet “The Wild Chrysantheme”, op. -

Violin, Viola, Cello

6144_Program 6/5/08 4:43 PM Page 1 The Board of the California Music Center would like to express our special thanks to Elizabeth Chamberlain a great friend of the Klein Competition. Her deep appreciation of music and young artists is an inspiration to all of us. 1 6144_Program 6/5/08 4:43 PM Page 2 The California Music Center and San Francisco State University present The Twenty-Third Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition June 11-15, 2008 with distinguished judges: Peter Gelfand Alan Grishman Marc Gottlieb Jennifer Kloetzel Patricia Taylor Lee Melvin Margolis Donna Mudge Alice Schoenfeld Franks Stemper First Prize: $10,000 The Irving M. Klein Memorial Award Second Prize: $5,000 The William M. Bloomfield Memorial Award Third Prize: $2,500 The Alice Anne Roberts Memorial Award Fourth Prizes: $1,500 The Thomas and Lavilla Barry Award The Jules and Lena Flock Memorial Award Additional underwriting provided by cgrafx, Inc., marketing & design Allen R. and Susan E. Weiss Memorial Prize: $200 For best performance of the commissioned work Each semifinalist not awarded a named prize will receive $1,000. 2 6144_Program 6/5/08 4:43 PM Page 3 In Memoriam Warren G. Weis 1922-1995 Warren G. Weis was a long-time supporter of the California Music Center and the Irving M. Klein International String Competition. He took great delight in music and his close association with musicians and teachers, and supported the aspirations of young musicians withs generosity and enthusiasm. Bill Bloomfield 1918-1998 A member of the Board of the Competition, Bill Bloomfield was an amateur musician and a lifelong supporter sand enthusiast of music and the arts. -

Chamber Symphony Chamber Symphony

Chamber Symphony Chamber Symphony Commission commissioned by the See Hear! Program of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts Premiere 19 May 2005 in Perelman Theater, Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, Philadelphia, PA by the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, Jeri Lynne Johnson, conductor Instrumentation flute (doubling piccolo) oboe clarinet in B-flat (doubling clarinet in E-flat) bassoon 2 horns in F trumpet in C trombone 3 violins 3 violas 3 violoncellos 2 contrabasses Duration approximately 20 minutes Copyright © 2005 by Jeremy Gill. All rights reserved. for my father Transposed Score J. Gill Chamber symphony (2005) q = 48 Flute doubling Piccolo non pp mf pp cresc. Oboe ppmf non pp cresc. Clarinet in B b doubling non Clarinet in E b pp mp pp cresc. Bassoon non pp mp pp cresc. Horn in F 1 pp mf Horn in F 2 pp mp Trumpet in C Trombone q = 48 3 Violins 1. 3 Violas 2.3. dal niente 3 Violoncellos dal niente 2 Contrabasses Copyright © 2005 by Jeremy Gill. All rights reserved. 2 8 , Fl. mf pp , Ob. mf pp , Cl. mf pp , Bsn mf pp , Hn 1 pp mf pp , Hn 2 pp mf pp div. a3 Vlns pp flautando 1. pp flautando Vlas 2.3. cresc. poco a p poco 1. p Vcs cresc. poco a poco 2.3. cresc. poco a poco p 3 15 Fl. pp mf f Ob. pp mf f Cl. pp f f Bsn pp f f Hn 1 pp mf Hn 2 pp f Vlns div. a3 1. mp Vlas 2.3. -

Listening Guide Chamber Symphony in F Major Op

Listening Guide Chamber Symphony in F major Op. 73a by Dimitri Shostakovich (arr. Barshai) This listening guide will explore the historical, cultural, and musical factors that make Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony in F major Op. 73a unique. After exploring this listening guide, you will have a better understanding of the musical features of this emotional work. Contents Description ........................................................................................................................................................ - 2 - Historical Context .......................................................................................................................................... - 2 - Listening Guide ................................................................................................................................................. - 4 - I. Allegretto (a fairly brisk speed) ............................................................................................................. - 4 - II. Moderato con moto (a moderate speed with motion) ........................................................................... - 5 - III. Allegro non troppo (fast and lively but not too fast) .............................................................................. - 6 - IV. Adagio (slow) ........................................................................................................................................ - 7 - V. Moderato (a moderate speed) ............................................................................................................. -

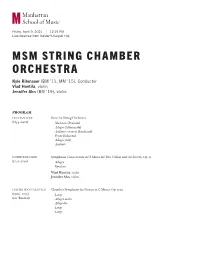

Msm String Chamber Orchestra

Friday, April 9, 2021 | 12:15 PM Livestreamed from Neidorff-Karpati Hall MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA Kyle Ritenauer (BM ’11, MM ’15), Conductor Vlad Hontila, violin Jennifer Ahn (BM ’19), violin PROGRAM LEOS JANÁČEK Suite for String Orchestra (1854–1928) Moderato (Prelude) Adagio (Allemande) Andante con moto (Saraband) Presto (Scherzo) Adagio (Air) Andante JOSEPH BOLOGNE Symphonie Concertante in G Major for Two Violins and Orchestra, Op. 13 (1745–1799) Allegro Rondeau Vlad Hontila, violin Jennifer Ahn, violin DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Chamber Symphony for Strings in C Minor, Op. 110a (1906–1975) Largo (arr. Barshai) Allegro molto Allegretto Largo Largo MSM STRING CHAMBER ORCHESTRA VIOLIN 1 VIOLIN 2 VIOLA DOUBLE BASS HORN Corinne Au Selin Algoz Leah Glick Dylan Holly Emma Potter Short Hills, New Jersey Istanbul, Turkey Jerusalem, Israel Tucson, Arizona Surprise, Arizona Ally Cho Luxi Wang Dudley Raine Sophia Filippone Melbourne, Australia Sichuan, China Lynchburg, Virginia OBOE Glen Mills, Pennsylvania Messiah Ahmed Carolyn Carr Ellen O’Neill Dallas, Texas Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania CELLO New York, New York Edward Luengo Andres Ayola Miami, Florida New York, New York Pedro Bonet Madrid, Spain Students in this performance are supported by the L. John Twiford Music Scholarship, and the Herbert R. and Evelyn Axelrod Scholarship. We are grateful to the generous donors who made these scholarships possible. For information on establishing a named scholarship at Manhattan School of Music, please contact Susan Madden, Vice President for Advancement, at 917-493-4115 or [email protected]. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Kyle Ritenauer, Conductor Acclaimed New York-based conductor Kyle Ritenauer is establishing himself as one of classical and contemporary music’s singular artistic leaders. -

July 4 Concert Launches Chamber Symphony Series

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 6-26-1974 July 4 concert launches Chamber Symphony series University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "July 4 concert launches Chamber Symphony series" (1974). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 23473. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/23473 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~news Information Services University of mon ana • missoula, montana 59801 • (406) 243-2522 FMMED IA TE LY dwyer, 243-4970 ~./26/74 local JULY 4 CONeERT LAUNCHES CHAHBER SYMPHONY SEJliES The MOntana Chamber Symphony opens its second concert season with a Fourth-of-July per- Eormance at 8 p. m. in the Music Recital Hall on the University of Montana campus. The con- ~ert is open to the public without charge. The 40-member orchestra, directed by Eugene Andrie, professor of music in the UM School of Fine Arts, will perform Moza~t's Sinphonie Concertant in E flat, with visiting professors hristopher Kimber, violinist, and Karin Pugh, violist, as soloists, and Faure's Elegie for polo Cello and Orchestra, with Florence Reynolds of the UM music faculty as soloist. -

Lietuvos Muzikologija 17.Indd

Lietuvos muzikologija, t. 17, 2016 Levon HAKOBIAN Levon HAKOBIAN The Modernist Trend in Soviet Russian Music Between the Wars: An Isolated Episode or a Part of Big Current? Modernizmo tendencija Sovietų Rusijos tarpukario muzikoje: pavienis epizodas ar didesnės srovės dalis? Abstract For a long time the modernist music created in the Soviet Union during the 1920s was not treated in the international scholarship as something truly valuable. Although in the early 1980s the attitudes began to change, an opinion is still in force that “the Russian musical avant-garde [of the early 20th century] is notable not so much for its achievements in professional musical composition, as for the intensity and conceptual boldness of its aspirations” (Andreas Wehrmeyer). This, indeed, may be the case with some minor figures that were active around 1917, but it would be unfair to underestimate the scope and importance of the innovatory trend in Russian (now already Soviet) music of the 1920s, whose influence was felt well into the 1930s. The trend in question was an integral part of both the international modernism of that time and the modernist movements in Russian literature, theatre, and visual arts (which for some time seemed to be compatible with the Communist ideology). Its production, apart from works by Nikolai Roslavetz, Vladimir Deshevov, Leonid Polovinkin, Alexander Mosolov and some other composers, includes at least several large-scale masterpieces, stylistically gravitating towards the extremes of the international avant- garde: Dmitri Shostakovich’s The Nose and To October, Gavriil Popov’s First Symphony, Sergei Prokofiev’s Cantata to the 20th Anniversary of the October Revolution. -

Boston Symphony Chamber Players 50Th Anniversary Season 2013-2014

Boston Symphony Chamber Players 50th anniversary season 2013-2014 jordan hall at the new england conservatory october 13 january 12 february 9 april 6 BOSTON SYMPHONY CHAMBER PLAYERS Sunday, February 9, 2014, at Jordan Hall at New England Conservatory TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Welcome 4 From the Players 8 Today’s Program Notes on the Program 10 Charles Martin Loeffler 12 Kati Agócs 13 Gunther Schuller 14 Hannah Lash 15 Yehudi Wyner 17 Amy Beach Artists 18 Boston Symphony Chamber Players 19 Randall Hodgkinson 19 Andris Poga 20 The Boston Symphony Chamber Players: Concert Repertoire, 1964 to Date COVER PHOTO (top) Founding members of the Boston Symphony Chamber Players, 1964: (seated, left to right) Joseph Silverstein, violin; Burton Fine, viola; Jules Eskin, cello; Doriot Anthony Dwyer, flute; Ralph Gomberg, oboe; Gino Cioffi, clarinet; Sherman Walt, bassoon; (standing, left to right) Georges Moleux, double bass; Everett Firth, timpani; Roger Voisin, trumpet; William Gibson, tombone; James Stagliano, horn (BSO Archives) COVER PHOTO (bottom) The Boston Symphony Chamber Players in 2012 at Jordan Hall: (seated in front, from left): Malcolm Lowe, violin; Haldan Martinson, violin; Jules Eskin, cello; Steven Ansell, viola; (rear, from left) Elizabeth Rowe, flute; John Ferrillo, oboe; William R. Hudgins, clarinet; Richard Svoboda, bassoon; James Sommerville, horn; Edwin Barker, bass (photo by Stu Rosner) ADDITIONAL PHOTO CREDITS Individual Chamber Players portraits pages 4, 5, 6, and 7 by Tom Kates, except Elizabeth Rowe (page 6) and Richard Svoboda (page 7) by Michael J. Lutch. Boston Symphony Chamber Players photos on page 8 by Stu Rosner and on page 18 by Michael J. -

LINER NOTES Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc

The Vision of Francis Goelet When and if the story of music patronage in the United States is ever written, Francis Goelet will emerge as the single most important individual supporter of composers as well as musical institutions and organizations that we’ve ever had. Unlike donors of buildings—museums, concert halls, and theaters—where names of donors are often prominently displayed, music philanthropy is apt to be noted when a piece is first performed and then is likely to fade into history. In the course of Francis Goelet’s lifetime he commissioned more symphonic and operatic works than any other American citizen. He paid for or contributed toward the staging of seventeen productions at the Metropolitan Opera, including three world premieres: Samuel Barber’s Vanessa and Antony and Cleopatra and John Corigliano’s The Ghosts of Versailles—but his most significant contribution was the commissioning of new music, starting in 1967 with a series of works to celebrate the New York Philharmonic’s 125th anniversary. Several of these have become twentieth-century landmarks. In 1977 he commissioned a series of concertos for the Philharmonic’s first-desk players, and to celebrate the Philharmonic’s 150th anniversary in 1992, he paid for another thirty-six works. Beginning with the American Composers Orchestra’s tenth anniversary he commissioned twenty-one symphonic scores, primarily from emerging composers. When New World Records was created in 1975 by the Rockefeller Foundation to celebrate American music at the time of our bicentennial celebrations, he was invited on the board and became its vice-chairman. At the conclusion of the Bicentennial he underwrote New World Records on his own, and this recording is a result of a continuation of his extraordinary legacy. -

Christine E. Moore DEGREES PRESENT EMPLOYMENT

Christine E. Moore DEGREES BM University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 1973-1977 Viola Performance Teacher Certification, Iowa, All Levels MA Western Illinois University, Macomb, Illinois 1977-1979 Viola Performance Teaching Assistantship, Suzuki Program MS University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana 1993-1995 Library and Information Science PRESENT EMPLOYMENT 1995 -- Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, Texas Music Librarian Administers the Music Library Provide Music Reference for students, faculty, and community members Provided General Reference, John B. Coleman Library until May 2003 Manage electronic reserve pages for Department of Music and Theatre Collection Development: evaluating donations to Music Library Ordering sound recordings for Music Library Ordering videos, DVDs, and books for Coleman Library and Music Library Coordinate cataloging of music materials Supervise, train and evaluate student workers Advise music majors Writes library reports for NASM accreditation purposes String Instructor Teach String Instruments class for music education majors Teach applied string lessons for music majors and minors 2003-- Musicpassion Personal business for teaching violin and viola in my home PREVIOUS EMPLOYMENT 2001-2004 3D Math Academy, Prairie View, Texas Violin Instructor 2001-2003 KD Music and Arts, Katy, Texas Violin and Viola Instructor 1994-1995 Music Library, University of Illinois, Champaign Urbana Internship, Fall semester 1994 Graduate research grant assisting Mrs. Leslie Troutman, Librarian 1993-1995 The Conservatory of -

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Born in St. Petersburg. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13 and studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. His graduation piece, the Symphony No. 1, gave him immediate fame and from there he went on to become the greatest composer during the Soviet Era of Russian history despite serious problems with the political and cultural authorities. He also concertized as a pianist and taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He was a prolific composer whose compositions covered almost all genres from operas, ballets and film scores to works for solo instruments and voice. Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor with Trumpet and String Orchestra, Op. 35 (1933) Dmitri Alexeyev (piano)/Philip Jones (trumpet)/Jerzy Maksymiuk/English Chamber Orchestra ( + Piano Concerto No. 2, Unforgettable Year 1919, Gadfly: Suite, Tahiti Trot, Suites for Jazz Orchestra Nos. 1 and 2) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE 382234-2 (2007) Victor Aller (piano)/Murray Klein (trumpet)/Felix Slatkin/Concert Arts Orchestra ( + Hindemith: The Four Temperaments) CAPITOL P 8230 (LP) (1953) Leif Ove Andsnes (piano)/Håkan Hardenberger (trumpet)/Paavo Järvi/City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra ( + Britten: Piano Concerto and Enescu: Legende) EMI CLASSICS 56760-2 (1999) Annie d' Arco (piano)/Maurice André (trumpet)/Jean-François Paillard/Orchestre de Chambre Jean François Paillard (included in collection: "Maurice André Edition - Volume