An Updated Description of the Australian Dingo (Canis Dingo Meyer, 1793) M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Dingo [Western Australia]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5448/dingo-western-australia-555448.webp)

Dingo [Western Australia]

Farmnote 133/2000 : Dingo [Western Australia] Dingo Farmnote 133/2000 By Peter Thomson, Vertebrate Pest Research Section, Forrestfield The dingo or wild dog (Canis familiaris dingo) is found across most of Western Australia. It is subject to management programs in grazing areas because of its predation of livestock. Name 'Dingo' was the name recorded in the early days of European settlement in New South Wales for the 'dogs' belonging to the local Aborigines. 'Warrigal' is one of the central Australian Aboriginal names for the dingo. Although the dingo was classified in the same species as the domestic dog (Canis familiaris), it was probably never exposed to the processes of artificial selection that eventually produced the modern domestic dog. A suggested change in scientific name to Canis lupus dingo reflects the origin of dingoes from wolves (Canis lupus) and the separation of dingoes from domestic dogs. Farmnote 133/2000 : Dingo [Western Australia] Origin The dingo is a primitive dog that evolved from the Indian or Pallid wolf and became widespread throughout southern Asia between 6000 and 10,000 years ago. It is now believed that dingoes were introduced into Australia about 4000 years ago by Asian seafarers, rather than during an Aboriginal migration. Description Dingoes are anatomically very similar to domestic dogs with which they are able to interbreed. They are usually sandy red or ginger in colour, with white feet and a white tail tip. White dingoes and black and tan individuals are also found. Patchy colouration or brindling is a sign of hybridisation with domestic dogs. Occurrence Dingoes are found through much of the state. -

This Is the Authors' Post-Print PDF Version

This is the authors’ post-print PDF version of the paper ‘Wild dogs and village dogs in New Guinea: Were they different?’ which was published in Australian Mammalogy. Citation details for the published version are: Dwyer, P. D. and M. Minnegal (2016) Wild dogs and village dogs in New Guinea: Were they different? Australian Mammalogy 38(1): 1-11. DOI: 10.1071/AM15011 WILD DOGS AND VILLAGE DOGS IN NEW GUINEA: WERE THEY DIFFERENT? PETER D. DWYER and MONICA MINNEGAL Recent accounts of wild-living dogs in New Guinea argue that these animals qualify as an “evolutionarily significant unit” that is distinct from village dogs, have been and remain genetically isolated from village dogs and merit taxonomic recognition at, at least, subspecific level. These accounts have paid little attention to reports concerning village dogs. This paper reviews some of those reports, summarizes observations from the interior lowlands of Western Province and concludes that: (1) at the time of European colonization, wild- living dogs and most, if not all, village dogs of New Guinea comprised a single though heterogeneous gene pool; (2) eventual resolution of the phylogenetic relationships of New Guinea wild-living dogs will apply equally to all or most of the earliest New Guinea village-based dogs; and (3) there remain places where the local village-based population of domestic dogs continues to be dominated by individuals whose genetic inheritance can be traced to pre- colonization canid forebears. At this time, there is no firm basis from which to assign a unique Linnaean name to dogs that live as wild animals at high altitudes of New Guinea. -

The Wayward Dog: Is the Australian Native Dog Or Dingo a Distinct Species?

Zootaxa 4317 (2): 201–224 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4317.2.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:3CD420BC-2AED-4166-85F9-CCA0E4403271 The Wayward Dog: Is the Australian native dog or Dingo a distinct species? STEPHEN M. JACKSON1,2,3,9, COLIN P. GROVES4, PETER J.S. FLEMING5,6, KEN P. APLIN3, MARK D.B. ELDRIDGE7, ANTONIO GONZALEZ4 & KRISTOFER M. HELGEN8 1Animal Biosecurity & Food Safety, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange, New South Wales 2800, Australia. 2School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052. 3Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 4School of Archaeology & Anthropology, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia. E: [email protected]; [email protected] 5Vertebrate Pest Research Unit, Biosecurity NSW, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange, New South Wales 2800, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 6 School of Environmental & Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, Australia. 7Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum, 1 William St. Sydney, NSW 2010, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 8School of Biological Sciences, Environment Institute, and ARC (Australian Research Council) Centre for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 9Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The taxonomic identity and status of the Australian Dingo has been unsettled and controversial since its initial description in 1792. -

Full Account (PDF)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Canis lupus Canis lupus System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Carnivora Canidae Common name Haushund (German), feral dog (English), domestic dog (English), kuri (Maori, New Zealand), guri (Maori), kurio (Tuamotuan), uli (Samoan), peto (Marquesan), pero (Maori) Synonym Canis dingo , Blumenbach, 1780 Canis familiaris , Linnaeus, 1758 Similar species Summary Canis lupus (the dog) is possibly the first animal to have been domesticated by humans. It has been selectively bred into a wide range of different forms. They are found throughout the world in many different habitats, both closely associated with humans and away from habitation. They are active hunters and have significant negative impacts on a wide range of native fauna. view this species on IUCN Red List Species Description Domestic dogs are believed to have first diverged from wolves around 100,000 years ago. Around 15,000 years ago dogs started diverging into the multitude of different breeds known today. This divergence was possibly triggered by humans changing from a nomadic, hunting based-lifestyle to a more settled, agriculture-based way of life (Vilà et al. 1997). Domestic dogs have been selectively bred for various behaviours, sensory capabilities and physical attributes, including dogs bred for herding livestock (collies, shepherds, etc.), different kinds of hunting (pointers, hounds, etc.), catching rats (small terriers), guarding (mastiffs, chows), helping fishermen with nets (Newfoundlands, poodles), pulling loads (huskies, St. Bernards), guarding carriages and horsemen (Dalmatians), and as companion dogs. Domestic dogs are therefore extremely variable but the basic morphology is that of the grey wolf, the wild ancestor of all domestic dog breeds. -

1944 Wolf Attacks on Humans: an Update for 2002–2020

1944 Wolf attacks on humans: an update for 2002–2020 John D. C. Linnell, Ekaterina Kovtun & Ive Rouart NINA Publications NINA Report (NINA Rapport) This is NINA’s ordinary form of reporting completed research, monitoring or review work to clients. In addition, the series will include much of the institute’s other reporting, for example from seminars and conferences, results of internal research and review work and literature studies, etc. NINA NINA Special Report (NINA Temahefte) Special reports are produced as required and the series ranges widely: from systematic identification keys to information on important problem areas in society. Usually given a popular scientific form with weight on illustrations. NINA Factsheet (NINA Fakta) Factsheets have as their goal to make NINA’s research results quickly and easily accessible to the general public. Fact sheets give a short presentation of some of our most important research themes. Other publishing. In addition to reporting in NINA's own series, the institute’s employees publish a large proportion of their research results in international scientific journals and in popular academic books and journals. Wolf attacks on humans: an update for 2002– 2020 John D. C. Linnell Ekaterina Kovtun Ive Rouart Norwegian Institute for Nature Research NINA Report 1944 Linnell, J. D. C., Kovtun, E. & Rouart, I. 2021. Wolf attacks on hu- mans: an update for 2002–2020. NINA Report 1944 Norwegian In- stitute for Nature Research. Trondheim, January, 2021 ISSN: 1504-3312 ISBN: 978-82-426-4721-4 COPYRIGHT © Norwegian -

The Australian Dingo: Untamed Or Feral? J

Ballard and Wilson Frontiers in Zoology (2019) 16:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12983-019-0300-6 DEBATE Open Access The Australian dingo: untamed or feral? J. William O. Ballard1* and Laura A. B. Wilson2 Abstract Background: The Australian dingo continues to cause debate amongst Aboriginal people, pastoralists, scientists and the government in Australia. A lingering controversy is whether the dingo has been tamed and has now reverted to its ancestral wild state or whether its ancestors were domesticated and it now resides on the continent as a feral dog. The goal of this article is to place the discussion onto a theoretical framework, highlight what is currently known about dingo origins and taxonomy and then make a series of experimentally testable organismal, cellular and biochemical predictions that we propose can focus future research. Discussion: We consider a canid that has been unconsciously selected as a tamed animal and the endpoint of methodical or what we now call artificial selection as a domesticated animal. We consider wild animals that were formerly tamed as untamed and those wild animals that were formerly domesticated as feralized. Untamed canids are predicted to be marked by a signature of unconscious selection whereas feral animals are hypothesized to be marked by signatures of both unconscious and artificial selection. First, we review the movement of dingo ancestors into Australia. We then discuss how differences between taming and domestication may influence the organismal traits of skull morphometrics, brain and size, seasonal breeding, and sociability. Finally, we consider cellular and molecular level traits including hypotheses concerning the phylogenetic position of dingoes, metabolic genes that appear to be under positive selection and the potential for micronutrient compensation by the gut microbiome. -

The Dogma of Dingoes—Taxonomic Status of the Dingo: a Reply to Smith Et Al

Zootaxa 4564 (1): 198–212 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4564.1.7 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:40FFF154-307F-43DD-8070-C0966AD427B5 The Dogma of Dingoes—Taxonomic status of the dingo: A reply to Smith et al. STEPHEN M. JACKSON1,2,3,4,*, PETER J.S. FLEMING5,6, MARK D.B. ELDRIDGE4, SANDY INGLEBY4, TIM FLANNERY7, REBECCA N. JOHNSON4,8, STEVEN J.B. COOPER9,10, KIEREN J. MITCHELL11,12, YASSINE SOUILMI11, ALAN COOPER11,12, DON E. WILSON3 & KRISTOFER M. HELGEN9,10,12, 1Biosecurity NSW, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange, New South Wales 2800, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 2School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia 3Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013-7012, United States of America. E-mail: [email protected] (Don E. Wilson) 4Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum, 1 William St. Sydney, New South Wales 2010, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (Mark D.B. Eldridge); [email protected] (Sandy Ingleby); [email protected] (Rebecca N. Johnson) 5Vertebrate Pest Research Unit, Biosecurity NSW, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange, New South Wales 2800, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 6Ecosystem Management, School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351, Australia 7Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia. -

Disentangling Canid Howls Across Multiple Species and Subspecies: Structure in a Complex Communication Channel

Disentangling canid howls across multiple species and subspecies: Structure in a complex communication channel Authors: Arik Kershenbaum, Holly Root-Gutteridge, Bilal Habib, Janice Koler-Matznick, Brian Mitchell, Vicente Palacios, & Sara Waller NOTICE: this is the author’s version of a work that was accepted for publication in Behavioural Processes. Changes resulting from the publishing process, such as peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms may not be reflected in this document. Changes may have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. A definitive version was subsequently published in Behavioural Processes, [VOL# 124, (March 2016)] DOI# 10.1016/j.beproc.2016.01.006 Kershenbaum, Arik , Holly Root-Gutteridge, Bilal Habib, Janice Koler-Matznick, Brian Mitchell, Vicente Palacios, and Sara Waller. "Disentangling canid howls across multiple species and subspecies: Structure in a complex communication channel." Behavioural Processes 124 (March 2016): 149-157. DOI: 10.1016/j.beproc.2016.01.006. Made available through Montana State University’s ScholarWorks scholarworks.montana.edu Elsevier Editorial System(tm) for Animal Behaviour Manuscript Draft Manuscript Number: Title: Disentangling canid howls across multiple species and subspecies: structure in a complex communication channel Article Type: UK Research paper Corresponding Author: Dr. Arik Kershenbaum, Corresponding Author's Institution: University of Cambridge First Author: Arik Kershenbaum Order of Authors: Arik Kershenbaum; Holly Root-Gutteridge; Bilal Habib; Janice Koler-Matznick; Brian Mitchell; Vicente Palacios; Sara Waller Abstract: Disentangling canid howls across multiple species and subspecies: structure in a complex communication channel Wolves, coyotes, and other canids are members of a diverse genus of top predators of considerable conservation and management interest. -

The Dogma of Dingoes—Taxonomic Status of the Dingo: a Reply to Smith Et Al

Zootaxa 4564 (1): 198–212 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4564.1.7 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:40FFF154-307F-43DD-8070-C0966AD427B5 The Dogma of Dingoes—Taxonomic status of the dingo: A reply to Smith et al. STEPHEN M. JACKSON1,2,3,4,*, PETER J.S. FLEMING5,6, MARK D.B. ELDRIDGE4, SANDY INGLEBY4, TIM FLANNERY7, REBECCA N. JOHNSON4,8, STEVEN J.B. COOPER9,10, KIEREN J. MITCHELL11,12, YASSINE SOUILMI11, ALAN COOPER11,12, DON E. WILSON3 & KRISTOFER M. HELGEN9,10,12, 1Biosecurity NSW, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange, New South Wales 2800, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 2School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales 2052, Australia 3Division of Mammals, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20013-7012, United States of America. E-mail: [email protected] (Don E. Wilson) 4Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum, 1 William St. Sydney, New South Wales 2010, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] (Mark D.B. Eldridge); [email protected] (Sandy Ingleby); [email protected] (Rebecca N. Johnson) 5Vertebrate Pest Research Unit, Biosecurity NSW, NSW Department of Primary Industries, Orange, New South Wales 2800, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] 6Ecosystem Management, School of Environmental and Rural Science, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351, Australia 7Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia. -

(Canis Lupus Dingo) on Risk Sensitive Foraging of Small Mammals in Forest Ecosystems Amanda Lu SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 Presence of the Dingo (Canis lupus dingo) on Risk Sensitive Foraging of Small Mammals in Forest Ecosystems Amanda Lu SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Environmental Policy Commons Recommended Citation Lu, Amanda, "Presence of the Dingo (Canis lupus dingo) on Risk Sensitive Foraging of Small Mammals in Forest Ecosystems" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1130. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1130 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Presence of the dingo (Canis lupus dingo) on risk sensitive foraging of small mammals in forest ecosystems Amanda Lu Project Advisor: Mike Letnic, Ph.D. Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, University of Western Sydney Sydney, Australia Academic Director: Tony Cummings Home Institution: Harvard University Major: Organismic and Evolutionary Biology Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Australia: Rainforest, Reef, and Cultural Ecology, SIT Study Abroad, Fall 2011 1 Abstract Trophic regulation of mesopredators through top order predators can have profound effects on ecosystem community and diversity. In the absence of top predators, invasive mesopredators exert strong selective pressures on native prey and can alter prey foraging behavior. When foraging in the presence of predators, prey must weigh predation risk against food gain. -

Making a New Dog?

Forum Making a New Dog? THOMAS M. NEWSOME, PETER J. S. FLEMING, CHRISTOPHER R. DICKMAN, TIM S. DOHERTY, WILLIAM J. RIPPLE, EUAN G. RITCHIE, AND AARON J. WIRSING We are in the middle of a period of rapid and substantial environmental change. One impact of this upheaval is increasing contact between humans and other animals, including wildlife that take advantage of anthropogenic foods. As a result of increased interaction, the evolution and function of many species may be altered through time via processes including domestication and hybridization, potentially leading to speciation events. We discuss the ecological and management importance of such possibilities, using gray wolves and other large carnivores as case studies. We identify five main ways that carnivores might be affected: changes to social structures, behavior and movement patterns, changes in survivorship across wild- to human-dominated environments, evolutionary divergence, and potential speciation. As the human population continues to grow and urban areas expand while some large carnivore species reoccupy parts of their former distributions, there will be important implications for human welfare and conservation policy. Keywords: Anthropocene, carnivore, domestication, hybridization, speciation rtificial selection and domestication have been In particular, although there is debate about the precise A integral to the success of humankind, who have been timing and location of gray-wolf domestication (to domestic exploiting the genetic diversity of plants and animals for over dogs, Canis familiaris; Larson et al. 2012), the mechanism by 12,000 years (Driscoll et al. 2009). Success, however, has come which wolves were domesticated is generally agreed to have at a cost: As a consequence of human-driven environmental been via their increasing reliance on anthropogenic foods change (the Anthropocene), the Earth is now experiencing (Zelder 2012). -

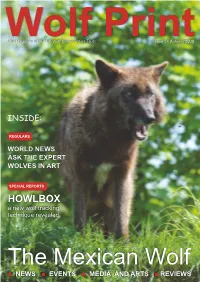

Issue 34 Autumn 2008

WolfThe Magazine of the UK Wolf Conservation Trust PrintIssue 34 Autumn 2008 INSIDE: REGULARS WORLD NEWS ASK THE EXPERT WOLVES IN ART SPECIAL REPORTS HOWLBOX a new wolf tracking technique revealed The Mexican Wolf ■ NEWS ■ EVENTS ■ MEDIA AND ARTS ■ REVIEWS UKWCT WOLF PRINT 1 Wolf Print Editor Toni Shelbourne Tel: 0118 971 3330 email: [email protected] Assistant Editor Julia Bohanna Editorial Team Sandra Benson, Vicky Hughes, Tsa Palmer, Denise Taylor Published by The UK Wolf Conservation Trust Editor's Letter Butlers Farm, Beenham, Reading RG7 5NT Tel & Fax: 0118 971 3330 hank you so much for the overwhelming response we had from email: [email protected] you all about the new style Wolf Print. The feedback was very Patrons positive and we have noted all the suggestions you gave us. Out David Clement Davies T Erich Klinghammer of 94 feedback forms that were returned: Desmond Morris · 48 thought it was excellent Michelle Paver Christoph Promberger · 36 thought is was very good · 8 thought is was good The UK Wolf Conservation Trust Directors · 1 thought it was fair Nigel Bulmer Anne Carter · 1 thought it was poor Charles Hicks Tsa Palmer · 9 people thought the level of content was too low Denise Taylor · 85 people thought it was just right The UK Wolf Conservation Trust is a company There was a vast array of things you wanted included in the magazine, limited by guarantee. Registered in England & Wales. ranging from more pictures, information on our wolves, our activities Company No. 3686061 and wolves in other UK zoos, member's photo page, history of wolves in The opinions expressed in this magazine are not the UK, profiles on staff and volunteers, conservation updates from necessarily those of the publishers or The UK Wolf around the world, information on wolf holidays and a kids' page.