Download Taunton Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

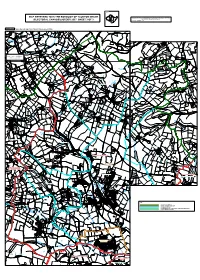

MAP REFERRED to in the BOROUGH of TAUNTON DEANE Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU

Sheet 3 3 MAP REFERRED TO IN THE BOROUGH OF TAUNTON DEANE Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU. 2 1 Tel: 023 8030 5092 Fax: 023 8079 2035 (ELECTORAL CHANGES) ORDER 2007 SHEET 3 OF 3 © Crown Copyright 2007 SHEET 3, MAP 3 Taunton Deane Borough. Parish Wards in Bishop's Lydeard Parish E N A L E AN D L L OO O P O D W UN RO Roebuck Farm Wes t So mer set Rai lway A 3 5 8 Ashfield Farm Aisholt Wood Quarry L (dis) IL H E E R T H C E E B Hawkridge Common All Saints' Church E F Aisholt AN L L A TE X Triscombe A P Triscombe Quarry Higher Aisholt G O Quarries K O Farm C (Stone) (disused) BU L OE H I R L L Quarry (dis) Flaxpool Roebuck Gate Farm Quarry (dis) Scale : 1cm = 0.1000 km Quarry (dis) Grid interval 1km Heathfield Farm Luxborough Farm Durborough Lower Aisholt Farm Caravan G Site O O D 'S L Triscombe A N W House Quarry E e Luxborough s t (dis) S A Farm o 3 m 5 8 e Quarry r s e (dis) t R a i l w a y B Quarry O A (dis) R P A T H L A N E G ood R E E N 'S Smokeham R H OCK LANE IL Farm L L HIL AK Lower Merridge D O OA BR Rock Farm ANE HAM L SMOKE E D N Crowcombe e A L f Heathfield K Station C O R H OL FO Bishpool RD LA Farm NE N EW Rich's Holford RO AD WEST BAGBOROUGH CP Courtway L L I H S E O H f S H e E OL S FOR D D L R AN E E O N Lambridge H A L Farm E Crowcombe Heathfield L E E R N H N T E K Quarry West Bagborough Kenley (dis) Farm Cricket Ground BIRCHES CORNER E AN Quarry 'S L RD Quarry (dis) FO BIN (dis) D Quarry e f (dis) Tilbury Park Football Pitch Coursley W e s t S Treble's Holford o m e E Quarry L -

The Mill Cottage the Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles

The Mill Cottage The Mill Cottage Cockercombe, Over Stowey, Bridgwater, TA5 1HJ Taunton 8 Miles • 4.2 Acres • Stable Yard • Mill Leat & Stream • Parkland and Distant views • 3 Reception Rooms • Kitchen & Utility • 3 Bedrooms (Master En-Suite) • Garden Office Guide price £650,000 Situation The Mill Cottage is situated in the picturesque hamlet of Cockercombe, within the Quantock Hills, England's first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. This is a very attractive part of Somerset, renowned for its beauty, with excellent riding, walking and other country pursuits. There is an abundance of footpaths and bridleways. The village of Nether Stowey is 2 miles away and Kingston St A charming Grade II Listed cottage with yard, stabling, 4.2 Acres of Mary is 5 miles away. Taunton, the County Town of Somerset, is some 8 miles to the South. Nether Stowey is an attractive centre land and direct access to the Quantock Hills. with an extensive range of local facilities, which are further supplemented by the town of Bridgwater, some 8 miles to the East. Taunton has a wide range of facilities including a theatre, county cricket ground and racecourse. Taunton is well located for national communications, with the M5 motorway at Junction 25 and there is an excellent intercity rail service to London Paddington (an hour and forty minutes). The beautiful coastline at Kilve is within 15 minutes drive. Access to Exmoor and the scenic North Somerset coast is via the A39 or through the many country roads in the area. The Mill Cottage is in a wonderful private location in a quiet lane, with clear views over rolling countryside. -

Breach Barton Breach Barton West Bagborough, Taunton, TA4 3EE Bishops Lydeard - 2 Miles, Kingston St Mary -4 Miles, Taunton - 9 Miles

Breach Barton Breach Barton West Bagborough, Taunton, TA4 3EE Bishops Lydeard - 2 Miles, Kingston St Mary -4 Miles, Taunton - 9 Miles • Excellent Riding • Indoor and Outdoor Arenas • 36 Acres • 5 Bedroom Farmhouse • Extensive Stabling • Level Fenced Paddocks • Private Location • 2 Bedroom Cottage Guide price £1,350,000 Situation Breach Barton occupies a sensational location on the lower slopes of the Quantock Hills. The property is elevated, has no near neighbours and enjoys commanding views south of the surrounding countryside. The property is approached from a quiet country lane, and enjoys a high level of privacy. For those with riding and walking interests, the location is unbeatable, as the Quantock Hills offer miles of footpaths and bridleways and is designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. From the properties south facing location there are magnificent views which stretch over the Vale A stunning country house with a 2 bedroom cottage & excellent of Taunton towards the Blackdown Hills as well as to the west overlooking the Brendons and Exmoor. The north of the property has stunning views into the Quantock Hills. equestrian facilities. Although the property is private and peaceful it is not isolated as the village of West Bagborough is only ½ a mile away. This is a thriving community with a well-known local pub and church. Bishops Lydeard is approximately 2 miles away where an extensive range of day to day facilities can be found. Taunton the County Town is 9 miles away and has a more extensive range of shopping and leisure facilities including the County Cricket Ground, Taunton Racecourse and many excellent public and state schools. -

Lancelot - the Truth Behind the Legend by Rupert Matthews

Lancelot - The Truth behind the Legend by Rupert Matthews Published by Bretwalda Books at Smashwords Website : Facebook : Twitter This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author. First Published 2013 Copyright © Rupert Matthews 2013 Rupert Matthews asserts his moral rights to be regarded as the author of this book. ISBN 978-1-909698-64-2 CONTENTS Introduction Chapter 1 - Lancelot the Legend Chapter 2 - Lancelot in France Chapter 3 - Lancelot in Britain Conclusion Introduction Of all the Knights of the Round Table, none is so famous as Sir Lancelot. He is both the finest of the Arthurian knights, and the worst. He is the champion of the Round Table, and the reason for its destruction. He is loyal, yet treacherous. Noble, but base. His is a complex character that combines the best and worst of the world of chivalry in one person. It is Sir Lancelot who features in every modern adaptation of the old stories. Be it an historical novel, a Hollywood movie or a British TV series, Lancelot is centre stage. He is usually shown as a romantically flawed hero doomed to eventual disgrace by the same talents and skills that earn him fame in the first place. -

Topic Paper 1: Brief Assessment of Settlement Strategy Options January 2020

Local Plan 2040 - Issues and Options - Topic Paper 1 January 2020 LOCAL PLAN 2040 Topic Paper 1: Brief Assessment of Settlement Strategy Options January 2020 Prepared by: Stuart Todd BA (Hons), Dip.TRP, MRTPI Director, Stuart Todd Associates Ltd. 26th September, 2019 Local Plan 2040 - Issues and Options - Topic Paper 1 January 2020 This page is left intentionally blank Local Plan 2040 - Issues and Options - Topic Paper 1 January 2020 Contents 1. Introduction and Brief ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 2. Method ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Assumptions and Caveats ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 3. National Policy and Reasons for Consideration of Options ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

River Brue's Historic Bridges by David Jury

River Brue’s Historic Bridges By David Jury The River Brue’s Historic Bridges In his book "Bridges of Britain" Geoffrey Wright writes: "Most bridges are fascinating, many are beautiful, particularly those spanning rivers in naturally attractive settings. The graceful curves and rhythms of arches, the texture of stone, the cold hardness of iron, the stark simplicity of iron, form constant contrasts with the living fluidity of the water which flows beneath." I cannot add anything to that – it is exactly what I see and feel when walking the rivers of Somerset and discover such a bridge. From source to sea there are 58 bridges that span the River Brue, they range from the simple plank bridge to the enormity of the structures that carry the M5 Motorway. This article will look at the history behind some of those bridges. From the river’s source the first bridge of note is Church Bridge in South Brewham, with it’s downstream arch straddling the river between two buildings. Figure 1 - Church Bridge South Brewham The existing bridge is circa 18th century but there was a bridge recorded here in 1258. Reaching Bruton, we find Church Bridge described by John Leland in 1525 as the " Est Bridge of 3 Archys of Stone", so not dissimilar to what we have today, but in 1757 the bridge was much narrower “barely wide enough for a carriage” and was widened on the east side sometime in the early part of the 19th century. Figure 2 - Church Bridge Bruton Close by we find that wonderful medieval Bow Bridge or Packhorse Bridge constructed in the 15th century with its graceful slightly pointed chamfered arch. -

MAP REFERRED to in the BOROUGH of TAUNTONS DEANE O N a G E Portman Farm L Nurseries a N E

SHEET 1, MAP 1 Taunton Deane Borough. Ward boundaries in Taunton. Def East Lydeard Farm COTHELSTONE CP KEY Volis Farm E Kingston St Mary N A VC Primary School L Kingston St Mary N DISTRICT WARD BOUNDARY Hill Farm O T G N I PARISH BOUNDARY N D e N f E F PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY Water House Farm PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY Fulford Def V O L I S H I L Nursery L P A R MAP REFERRED TO IN THE BOROUGH OF TAUNTONS DEANE O N A G E Portman Farm L Nurseries A N E (ELECTORAL CHANGES)E ORDER 2007 SHEET 1 OF 3 N A L Pickney K R A P Created by the Ordnance Survey Boundaries Section, Southampton, SO16 4GU. Works Sheet 1 Scale : 1cm = 0.1000 km Tel: 023 8030 5092 Fax: 023 8079 2035 Hestercombe Grid interval 1km © Crown Copyright 2007 m a Hestercombe House e Hestercombe r t (Fire Brigade HQ) Farm Gotten ANE S PICKNEY L Nursery 3 n o t s Nailsbourne g in KINGSTON ST. MARY CP K 2 1 Lower Portman Farm BISHOP'S LYDEARD WARD Upper Cheddon ROAD Edgeborough OMBE TERC Farm HES BISHOP'S LYDEARD CP P I T C H E BISHOP'S LYDEARD PARISH WARD R ' S H I Deacons L STAPLEGROVE WARD L Conquest Farm Dodhill CHEDDON PARISH WARD Def A 3 B 58 ack S tream Fitzroy Cheddon Fitzpaine VC Primary School Stonehouse Farm Cheddon Fitzpaine W e s t S Higher Yarde o Rowford m Farm e rs e t R Longland's Farm a i lw a WEST MONKTON CP y King's Hall C CHEDDON FITZPAINE CP ok A Bro T s len' S Al E N L A A L N S E Y T Yarde Farm N O Vineyard M Pyrland D Hall Farm Y A e f Pyrland Farm W N E E R Sidbrook G Def E N A L D R O Ladymead F G Communtiy L -

Sol\IERSETSHIRE .. TAUNTON

DIRECTORY.] SOl\IERSETSHIRE .. TAUNTON. 357 • • J. Heathcote M.A. & the Rev. W. G. Fitzgerald hon. Clerk to the Trustees of the Market, Thomas J ames Shepherd, chaplains;- Rev. L. H. P. Maurica M.A. acting chaplain ; Castle green A Co. Capt. H. C. Sweet; B Co. Capt. E. T. Alms; Sergt. Collector of the Market, C. J. Fox, Castle green Major E. Willey, drill instructor Collector of Income & Assessed Taxes, St. Mary Magdalene Parish, William Waterman, 31 Paul street; St. James', TAUNTON UNION~ John Mattocks Chapman, 10 Canon street Board day, fortnightly, wednesday, at 2.go, at the Work Collector of Inland Revenue, Wm. Furze Bickford, Forest house. Collector of Poor Rates for St. Mary Magdalene Without, The Union comprises the following parishes :-Angersleigh, William Henry Wake, Church square; St. Mary :Magda Ash Priors, Bickenhall, Bishops Hull (Within & Without), lene Within, David Poole Hewer, Upper High street; St. Bishops Lydeard, Cheddon Fitzpaine, Churchstanton James Within & Without, John Mattocks Chapman, 10 (Devon), Combe Florey, Corfe, Cothelstone, Creech St. Canon street; Bishops Hull Within & Without, J. l\Iayes, Miehael, Curland, Durston, Halse, Hatch Beauchamp, Bishops Hull Heathfield, Kingston, Lydeard St. Lawrence, North County Analyst, Henry James Alford M.n., F.c.s. 2 :\'Iarl Curry, N orton Fitzwarren, Orchard Portman, Otterford, borough terrace Pitminster, Ruishton, Staplegrove, Staple Fitzpaine, County Surveyor, Charles Edmond Norman, 12 Hammet st Stoke St. Gregory, Stoke St. Mary, Taunton St. James Curator of Somerset Archreological & Natural History (Without & Within), Taunton St. Mary Magdalane (With Society, William Bidgood, The Castle out & Within), Thornfalcon, Thurlbear, Tolland, Trull, Deputy Clerk of the Peace for the. -

Corfe & Orchard Portman Somerset UK 1861 Census

1861 Census of Corfe Orchard Portman Somerset UK rg91613 Civil Parish ED Folio Page Schd House Address X Surname Forenames X Rel. C Sex Age X Occupation E X CHP Place of birth X Dis. W Notes Corfe 7 71 1 1 Hele Rd BODY Ann head W F 72y Farmer 20 acres SOM Bishops Lydeard blind BODY George son U M 46y Farmer 20 acres SOM Corfe BODY Betsy dau U F 42y Farmer's daughter SOM Corfe 2 Hele Rd DOBLE James head M M 54y Agricultural Labr Shepherd DEV Churchstanton DOBLE Jane wife M F 60y Labourers Wife DEV Clayhidon DOBLE Betsy dau U F 26y Seamstress DEV Churchstanton DOBLE James son U M 16y Ag Lab Carter DEV Churchstanton 3 Pickridge Hill SHUTE Charles head M M 41y Agricultural Labr SOM Corfe SHUTE Mary Ann wife M F 42y Ag Labr Wife SOM Stoke St Mary SHUTE John son U M 19y Ag Lab Son SOM Corfe SHUTE George son U M 14y Ag Lab Son SOM Corfe SHUTE Elizabeth dau U F 12y Scholar SOM Corfe SHUTE William son - M 10y Scholar SOM Corfe SHUTE Thomas son - M 5y Scholar SOM Corfe SHUTE Hannah dau - F 2y SOM Corfe 4 Pickridge Hill SHUTE William head W M 78y Labourer SOM Staple Fitzpaine 5 Poplar Cott HAKE John head M M 65y Carpenter SOM Staple Fitzpaine HAKE Mary Ann wife M F 65y Carpenter Wife SOM Curland 2 6 Whitford Rd VENN John head M M 43y Ag Lab SOM Corfe VENN Harriett wife M F 39y Ag Lab Wife SOM Staple Fitzpaine VENN James son U M 15y Ag Lab SOM Corfe VENN Charles son - M 12y Ag Lab SOM Corfe VENN Mary Ann dau - F 9y Scholar SOM Corfe VENN Emley dau - F 7y Scholar SOM Corfe VENN Elizabeth dau - F 5y Scholar SOM Corfe VENN John son - M 3y SOM Corfe -

The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain Free

FREE THE TIME TEAM GUIDE TO THE HISTORY OF BRITAIN PDF Tim Taylor | 320 pages | 05 Jul 2010 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9781905026708 | English | London, United Kingdom The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain by Tim Taylor Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. We all know that the Battle of Hastings was fought inLondon's 'one big burning blaze' tore through the capital in and that Britain declared war on Nazi Germany inbut many of us remember the most important moments in our history by the folk stories which are attached to them. So we remember Henry VIII for his wives rather than the Reformation The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain Charles We all know that the Battle of Hastings was fought inLondon's 'one big burning blaze' tore through the capital in and that Britain declared war on Nazi Germany inbut many of us remember the most important moments in our history by the folk stories which are attached to them. But if we set aside these stories, do we really know what happened when, and why it's so important? Which came first, the Bronze Age or the Stone Age? Why did the Romans play such a significant role in our past? And how did a nation as small as Britain come to command such a vast empire? Here, Tim Taylor and the team of expert historians behind Channel 4's Time Team, answer these questions and many more, cataloguing British history in a way that is accessible to all. -

Information Requests PP B3E 2 County Hall Taunton Somerset TA1 4DY J Roberts

Information Requests PP B3E 2 Please ask for: Simon Butt County Hall FOI Reference: 1700165 Taunton Direct Dial: 01823 359359 Somerset Email: [email protected] TA1 4DY Date: 3 November 2016 J Roberts ??? Dear Sir/Madam Freedom of Information Act 2000 I can confirm that the information you have requested is held by Somerset County Council. Your Request: Would you be so kind as to please supply information regarding which public service bus routes within the Somerset Area are supported by funding subsidies from Somerset County Council. Our Response: I have listed the information that we hold below Registered Local Bus Services that receive some level of direct subsidy from Somerset County Council as at 1 November 2016 N8 South Somerset DRT 9 Donyatt - Crewkerne N10 Ilminster/Martock DRT C/F Bridgwater Town Services 16 Huish Episcopi - Bridgwater 19 Bridgwater - Street 25 Taunton - Dulverton 51 Stoke St. Gregory - Taunton 96 Yeovil - Chard - Taunton 162 Frome - Shepton Mallet 184 Frome - Midsomer Norton 198 Dulverton - Minehead 414/424 Frome - Midsomer Norton 668 Shipham - Street 669 Shepton Mallet - Street 3 Taunton - Bishops Hull 1 Bridgwater Town Service N6 South Petherton - Martock DRT 5 Babcary - Yeovil 8 Pilton - Yeovil 11 Yeovil Town Service 19 Bruton - Yeovil 33 Wincanton - Frome 67 Burnham - Wookey Hole 81 South Petherton - Yeovil N11 Yeovilton - Yeovil DRT 58/412 Frome to Westbury 196 Glastonbury Tor Bus Cheddar to Bristol shopper 40 Bridport - Yeovil 53 Warminster - Frome 158 Wincanton - Shaftesbury 74/212 Dorchester -

EAST BRENT PARISH MAGAZINE (The Civil Parish of East Brent Consists of East Brent, Rooksbridge and Edingworth)

April 2017 Issue 25 EAST BRENT PARISH MAGAZINE (The Civil Parish of East Brent consists of East Brent, Rooksbridge and Edingworth) April 2017 Issue 25 A voluntary non-profit publication, free to Parishioners [ ] April 2017 Issue 25 [ 2 ] April 2017 Issue 25 Editor’s Notes By the time you read this we will have holidays for this year. My Wife and I put the clocks forward and will be haven’t yet decided where we shall having longer and, hopefully, warmer go, if we take one, but I rather fancy days and evenings which means that seeing a lot more of the North of the we can get out into the garden and UK; some of the magazine type start pruning, digging, planting and all programmes on TV show it off so of the other 1001 things that need to beautifully that I’m sold on it. If there be done – and then we can get the is anyone out there that is barbecues out!! contemplating a ‘different’ sort of At the time of writing, I see that there holiday, it may be, for example, a has been no response to either of the cycle or walking tour or an appeals in last month’s magazine, adventure/activity holiday, perhaps one for a Parish Councillor and the you might like to keep a journal and other to help us produce this share it with us – much the same as magazine – it’s not too late, just give Rachel Champion’s visit to Fiji. me a call if you want to talk about Personally, I enjoy reading about either of them.