University of Oklahoma Graduate College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harmony Crib Sheets

Jazz Harmony Primer General stuff There are two main types of harmony found in modern Western music: 1) Modal 2) Functional Modal harmony generally involves a static drone, riff or chord over which you have melodies with notes chosen from various scales. It’s common in rock, modern jazz and electronic dance music. It predates functional harmony, too. In some types of modal music – for example in jazz - you get different modes/chord scale sounds over the course of a piece. Chords and melodies can be drawn from these scales. This kind of harmony is suited to the guitar due to its open strings and retuning possibilities. We see the guitar take over as a songwriting instrument at about the same time as the modes become popular in pop music. Loop based music also encourages this kind of harmony. It has become very common in all areas of music since the late 20th century under the influence of rock and folk music, composers like Steve Reich, modal jazz pioneered by Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and influences from India, the Middle East and pre-classical Western music. Functional harmony is a development of the kind of harmony used by Bach and Mozart. Jazz up to around 1960 was primarily based on this kind of harmony, and jazz improvisation was concerned with the improvising over songs written by the classically trained songwriters and film composers of the era. These composers all played the piano, so in a sense functional harmony is piano harmony. It’s not really guitar shaped. When I talk about functional harmony I’ll mostly be talking about ways we can improvise and compose on pre-existing jazz standards rather than making up new progressions. -

Sonny Rollins Louis Sclavis Monika Roscher Eric Stach Patricia Kaas Gunter Hampel Jimmy Amadie

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC Sonny Rollins Louis Sclavis Monika Roscher Eric Stach Patricia Kaas Gunter Hampel Jimmy Amadie Sylvia Cuenca M Top Ten CDs and Concerts of 2013 JazzFest Berlin Int. jazz news jazz stories CD Reviews BooK REVIEWS in memory Volume 40 Number 1 Jan Feb Mar 2014 A HISTORICAL EDITION! Join us for 4 days of concerts sound art installations and visual arts Full program at www.fimav.qc.ca 15 to 18 May 2014 2 | CADENCE MAGAZINE | JAN FEB MAR 2014 4 | CADENCE MAGAZINE | JAN FEB MAR 2014 ___ IC 1001 Doodlin’ - Archie Shepp ___ IC 1070 City Dreams - David Pritchard ___ IC 1002 European Rhythm Machine - ___ IC 1071 Tommy Flanagan/Harold Arlen Phil Woods ___ IC 1072 Roland Hanna - Alec Wilder Songs ___ IC 1004 Billie Remembered - S. Nakasian ___ IC 1073 Music Of Jerome Kern - Al Haig ___ IC 1006 S. Nakasian - If I Ruled the World ___ IC 1075 Whale City - Dry Jack ___ IC 1012 Charles Sullivan - Genesis ___ IC 1078 The Judy Roberts Band ___ IC 1014 Boots Randolph - Favorite Songs ___ IC 1079 Cam Newton - Welcome Aliens ___ IC 1016 The Jazz Singer - Eddie Jefferson ___ IC 1082 Monica Zetterlund, Thad Jones/ ___ IC 1017 Jubilant Power - Ted Curson Mel Lewis Big Band ___ IC 1018 Last Sessions - Elmo Hope ___ IC 1083 The Glory Strut - Ernie Krivda ___ IC 1019 Star Dance - David Friesen ___ IC 1086 Other Mansions - Friesen/Stowell ___ IC 1020 Cosmos - Sun Ra ___ IC 1088 The Other World - Judy Roberts ___ IC 1025 Listen featuring Mel Martin ___ IC 1090 And In This Corner… - Tom Lellis ___ IC 1027 Waterfall -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963

A Collection of Stories and Memories by Members of the United States Naval Academy Class of 1963 Compiled and Edited by Stephen Coester '63 Dedicated to the Twenty-Eight Classmates Who Died in the Line of Duty ............ 3 Vietnam Stories ...................................................................................................... 4 SHOT DOWN OVER NORTH VIETNAM by Jon Harris ......................................... 4 THE VOLUNTEER by Ray Heins ......................................................................... 5 Air Raid in the Tonkin Gulf by Ray Heins ......................................................... 16 Lost over Vietnam by Dick Jones ......................................................................... 23 Through the Looking Glass by Dave Moore ........................................................ 27 Service In The Field Artillery by Steve Jacoby ..................................................... 32 A Vietnam story from Peter Quinton .................................................................... 64 Mike Cronin, Exemplary Graduate by Dick Nelson '64 ........................................ 66 SUNK by Ray Heins ............................................................................................. 72 TRIDENTS in the Vietnam War by A. Scott Wilson ............................................. 76 Tale of Cubi Point and Olongapo City by Dick Jones ........................................ 102 Ken Sanger's Rescue by Ken Sanger ................................................................ 106 -

Grad Jazz Theory Entrance Exam Review

REVIEW GUIDE GRADUATE JAZZ THEORY ENTRANCE EXAMINATION WRITTEN PORTION • Voicings – (Students who have completed the jazz piano requirement are exempt from this portion of the exam) All voicings required for the purpose of this exam will be rootless close-position voicings, and will fall under one of two categories: • Guide Tone voicings, which contain only the 3rd and 7th of each chord. • Four-Note Rootless voicings, which contain two guide tones and two color tones. The color tones should adhere to the following guidelines: • For Major and Minor chords, the 5th and 9th should be used. • For Dominant chords, the 6th (13th) and 9th should be used. • For Altered Dominant chords, the color tones will be specified by the chord symbol. • All voicings must be built up from a guide tone rather than a color tone. • All voiced chord progressions must use proper voice leading within the guidelines specified by the previous requirements. • Scales You will be asked to construct and/or identify the following scales in any key in either bass or treble clef: • Minor (Dorian, Aeolian,Phrygian, Harmonic, Melodic), • Major • Dominant • Lydian • Lydian Dominant • Diminished • Diminished Whole-Tone (a.k.a. "Altered) • Locrian • Locrian #2 • Whole Tone You may be asked to build any of these scales from the information contained in a chord symbol, or to name any scale based on a notated version. GRADUATE JAZZ THEORY ENTRANCE EXAMINATION, page 2 • Analysis • Key Center Analysis: You will be asked to provide a Key Center Analysis including Roman Numerals for a specified progression. Similar to the type of analysis common in traditional theory when analyzing modulations. -

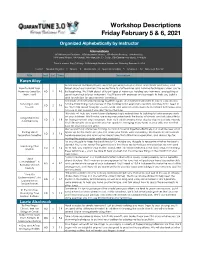

Workshop Descriptions Friday February 5 & 6, 2021

Workshop Descriptions Friday February 5 & 6, 2021 Organized Alphebetically by Instructor Abbreviations: HD=Hammered Dulcimer, MD=Mountain Dulcimer, BP=Bowed Psaltery, AH=Autoharp, PW=Penny Whistle, UK=Ukulele, MA=Mandolin, G= Guitar, CB+Clawhammer Banjo, FI=Fiddle Time is shown: Day (F=Friday, S=Saturday)-Session Number ex: Saturday Session 4 = S-4 Levels:1 = Absolute Beginner 2 = Novice 3 = Intermediate 4 = Upper Intermediate 5 = Advanced All = Non-Level Specific Title Inst. Lvl. Time Description Karen Alley As hammered dulcimer players, we often get wrapped up in notes and chords and tunes, and How to Hold Your forget about our hammers! The easiest time to start learning solid hammer technique is when you’re Hammers (and Use HD 1 F-3 first beginning. We’ll talk about different types of hammers, holding your hammers, and getting a Them, Too!) good sound out of your instrument. You’ll leave with exercises and concepts to help you build a solid foundation for your hammer technique. Someday soon we will be playing together again, and everyone will want to join in! Jam sessions Surviving a Jam can be intimidating if you’re new to the dulcimer (and even if you’re not!), but they don’t need to HD 2 F-4 Session be. We’ll talk about how jam sessions work, and work on simple melody and chord techniques you can use to join in even if you don’t know the tune. This class will help you move beyond playing single melody lines to building full solo arrangements on your dulcimer. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Am barré chord, 109 Numbers Am chord, 105 1-6-2-5 (I/VI7/II7/V7) progression, 253–254 Am scales, 147–149 2/2 time, 358 American folk style backing 2/4 time, 357 tracks, 302 2-5-1 (ii7/V7/I) progression, 261 A-model mandolin straps, 34 3/2 time, 357 anatomy of mandolins 3/4 time, 49 body, 17–18 4/4 time, 43 neck, 18–20 5/8 time, 357 overview, 15–16 6/8 time, 72 string vibrations, 20 8-bar blues, 178–179 andante, 358 12 scales, 249 anticipations, 258 12-bar blues, 177–178, 254–257 Aonzo, Carlo, 340 Apollon, Dave, 338 A armrest, 304 arpeggios, 140, 234–238 A barré chord, 109 articulations A chord, 55–56 ornamenting with, 197 A major scale, 139–141 types of, 97–102, 365–366 A5 mandolin, 285–286 ArtistWorks, 345 A7 barré chord, 109 A-style mandolins, 285–286 A7 chord, 108 audio tracks accents, 276–280, 365–366 accessing, 3–4 accessibility, 330–331 list of, 365–372 accessories kit, 297–303 listening to, 2 accidentals, 361 augmented chords, 127 acoustic concerts, 341–344 acoustic instrument shops, 294 action, 296 B adjusting, 321–322 B flat chord, 103 measurement for, 323 COPYRIGHTEDbackbeat, MATERIAL 176 adagio, 358 backing tracks, 302–303 Aeolian mode, 147, 219 bags, 319 allegro, 358 Bandolim, Jacob do, 338 alterations, defined, 135 bandolims, 239, 288 altered dominant chords, 251 barré chords, 106–109 alternate picking bars, 45 exercises, 84–86 bass clef, 356 general discussion, 69–71 Index 373 Index.indd 373 Trim size: 7.375 in × 9.25 in September 16, 2020 1:26 PM beats broken chords, 140 counting four, 43 bronze-wound strings, 309 -

Lucas Stephen M 2014 Masters

TRIPLE SYNTHESIS by Stephen Lucas A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO APRIL 2014 © STEPHEN LUCAS 2014 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis supervisors and committee members Professor Michael Coghlan and Professor Alan Henderson, for their guidance and support in the development of this thesis. I must also thank committee member Professor Holly Small for her generous input and support. In addition, I wish to thank my graduate studies Professors Dorothy de Val, Pat Bradley and David Mott for their advice and expert instruction in my coursework at York University. iii Abstract This thesis investigates the result of merging three musical approaches (jazz fusion, breakbeat/IDM and Electronic Dance Music) and their respective methodologies as applied to music composition. It is presented in a progressive manner. Chapters two to four identify and discuss each of the three styles separately in terms of the research undertaken in the preparation of this thesis. Chapter 2 discusses, through a close examination of selected compositions and recordings, both Weather Report and Herbie Hancock as representing source material for research and compositional study in terms of melody, harmony and orchestration from the 1970s jazz-fusion genre. Chapter 3 examines breakbeat and Intelligent Dance Music (IDM) drum rhythm programming through both technique and musical application. Chapter 4 presents an examination of selected contemporary Electronic Dance Music (EDM) techniques and discusses their importance in current electronic music styles. Chapters 5, 6 and 7 each present an original composition based on the application and synthesis of the styles and techniques explored in the previous three chapters, with each composition defined by proportions of influence from each of the three styles as in the Venn diagram shown in the introduction. -

HUG Songbook Volume 1 & 2 a Collection of Songs Used by the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

THE COMPENDIUM OF AWESOME! THE COMPLETE VOLUME 1 & 2 REVISED JANUARY 2016 The HUG Songbook Volume 1 & 2 A collection of songs used by the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada All of the songs contained within this book are for research and personal use only. Many of the songs have been simplified for playing at our club meetings. General Notes: ¶ The goal in assembling this songbook was to pull together the bits and pieces of music used at the monthy gatherings of the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) ¶ Efforts have been made to make this document as accurate as possible. If you notice any errors, please contact us at http://halifaxukulelegang.wordpress.com/ ¶ The layout of these pages was approached with the goal to make the text as large as possible while still fitting the entire song on one page ¶ Songs have been formatted using the ChordPro Format: The Chordpro-Format is used for the notation of Chords in plain ASCII-Text format. The chords are written in square brackets [ ] at the position in the song-text where they are played: [Em] Hello, [Dm] why not try the [Em] ChordPro for[Am]mat ¶ Many websites and music collections were used in assembling this songbook. In particular, many songs in this volume were used from https://ukutabs.com/, Richard G’s Ukulele Songbook (http://www.scorpex.net/uke.htm), the Bytown Ukulele Group website (http://www.bytownukulele.ca/) and the BURP (Berkhamsted Ukulele Random Players) website (http://www.hamishcurrie.me.uk/burp/index.htm). ¶ Ukulizer (http://www.ukulizer.com/) was used to transpose many songs into ChordPro format. -

A LOT of SONGS Version 3

SyraUke Songbook VERSION 3.0 revised July 2017 Cruel to Be Kind SONGS Dance A Little Longer Daydream 9 To 5 Deep River Blues Across the Universe Deportees After Hours Velvet Underground Dig A Little Deeper In The Well Ain’t She Sweet Dirty Old Town Alcohol Do You Believe In Magic All I Have To Do Is Dream Don’t Think Twice All the Best Dont Worry Be Happy All-of-Me Down At The Twist and Shout Always Look On The Bright Side Of Life Down by the Water Anarchy in the UK Dream A Little Dream Of Me Anchored in Love Drinking Song And I Love Her Elephant gun Angel Band End of the Line The Angel from montgomery Enjoy the Silence Annabelle Every Day Apeman Everybody Knows Apple Blossom Everybody Talks Apple Jack Fannin Street At Last Farther Along At the Beach First of the gang to die Babylon Fish And Whistle Back on the Chain Gang Five Foot Two Bad Reputation Five Years Time Banana In Your Fruit Basket Fly Me to the Moon Banks of Marble Folsom Prison Blues Banks of the Ohio Freight Train-libba cotten-C Best Ever Death Metal Band In Denton Freight Train-libba cotten-F Big Rock Candy Mountain Harry McClintok Freight Train Bird On The Wire Fuck You I’m Drunk Blister In The Sun Violent Femmes Fuck You/ Forget You Blitzkreig Bop Gardener The Blowin’ in the Wind Genevieve Blue Monday Girl The Blue Red and Grey God gonna cut you down Blues Stay Away from Me Going Down this Road Feeling Bad Book of Love Goodbye Born to Run Goodnight Irene Brand New Key Grandpa was a Carpenter Bread and Roses Hallelujah Im a Bum-C Breaking Up Is Hard To Do Hallelujah Brown -

Covered by Rainbow Written by Russell Ballard Since You’Ve Been Gone Musical Contexts

SINCE YOU’VE BEEN GONE Covered by Rainbow Written by Russell Ballard Since You’ve Been Gone Musical Contexts ■ First written by Russell (Russ) Ballard in 1976 on his album Winning. ■ Covered by the band Rainbow in 1979 on their album Down to Earth and became a top 10 UK single. ■ Described as one of the best rock songs of all time. Rainbow - A British rock band led by guitarist Russell (Russ) Ballard – Singer, Guitarist, Ritchie Blackmore that has operated in different Songwriter and Producer. Lead vocalist and times and with different personnel (except for guitarist for the band Argent who became a Ritchie) from 1975 to the present. Their successful songwriter and producer in the commercial breakout came with Since You’ve 1970s. His compositions Since You’ve Been Been Gone in 1979. They play in Pop-Rock style Gone and I Surrender became hits for (Hard Rock, Heavy Metal). Rainbow. Since You’ve Been Gone Musical Elements lv. 1 ■ Instrumentation (Timbre) - Rock Band: Drum kit, lead and bass guitars, keyboard, lead singer Since You’ve Been Gone Musical Elements lv. 1 ■ Tempo - Moderately bright rock beat ( approx. 121 bpm) Since You’ve Been Gone Musical Elements lv. 1 ■ Dynamics - Mainly forte, although bridge is slightly quieter Since You’ve Been Gone Musical Elements lv. 1 ■ Rhythm – Lots of different rhythms used: clear riff pattern is evident, rhythms of the melody looks complex but follows the rhythms of the words; syncopation – 4/4 time throughout except one 2/4 bar in the intro) Since You’ve Been Gone Musical Elements lv. -

Crazy Rhythm Music by JOSEPH MEYER and ROGER WOLFE KAHN Arranged by MIKE LEWIS

CRAZY RHYTHM Music by JOSEPH MEYER and ROGER WOLFE KAHN Arranged by MIKE LEWIS INSTRUMENTATION Conductor 1st Trombone Optional Alternate Parts 1st E Alto Saxophone 2nd Trombone C Flute b 2nd E Alto Saxophone 3rd Trombone (Optional) Tuba b 1st B Tenor Saxophone 4th Trombone (Optional) Horn in F b 2nd B Tenor Saxophone Guitar Chords (Doubles 1st Trombone) b E Baritone Saxophone Guitar (Optional) 1st Baritone T.C./B Tenor Saxophone b (Optional) Piano (Doubles 1st Trombone)b 1st B Trumpet Bass 2nd Baritone T.C./B Tenor Saxophone b 2nd B Trumpet Drums (Doubles 2nd Trombone)b 3rd B b Trumpet 4th Bb Trumpet (Optional) b Preview Only Legal Use Requires Purchase CRAZY RHYTHM Music by JOSEPH MEYER and ROGER WOLFE KAHN Arranged by MIKE LEWIS NOTES TO THE CONDUCTOR “Crazy Rhythm” is a standard composed way back in 1928 for the musical, Here’s Howe. As with many show tunes, this song has become a standard performed by countless jazz instrumentalists and vocalists worldwide. This chart is played as a moderate swing tempo with some unusual rhythmic patterns that showcase ensemble blending and a variety of jazz articulations. Saxes should not use vibrato in the unison intro. A general rule in jazz is all unisons should be played without vibrato. There is a somewhat challenging rhythmic pattern in measure 41 which gives the musical illusion of changing the meter to 3/4 time. Be sure to count through and it comes out even after 4 measures—after all, it is “Crazy Rhythm.” I suggest spending some time working Mike Lewis with this section.