Mayall II ≡ G1 in M31: Giant Globular Cluster Or Core of a Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observation of Pc 3/5 Magnetic Pulsations Around the Cusp at Mid Altitude

1 OBSERVATION OF PC 3/5 MAGNETIC PULSATIONS AROUND THE CUSP AT MID ALTITUDE Liu Yonghua(1), Liu Ruiyuan(1), B. J. Fraser(2), S. T. Ables(2), Xu Zhonghua(1), Zhang Beichen(1), Shi Jiankui(3), Liu Zhenxing(3), Huang Dehong(1), Hu Zejun(1), Chen Zhuotian(1), Wang Xiao(3), Malcolm Dunlop(4), A. Balogh(5) (1) Polar Research Institute of China, 451 Jinqiao Rd., Shanghai 200136, P. R. CHINA, [email protected] (2) The University of Newcastle, University Drive, Callaghan NSW 2308, AUSTRALIA, [email protected] (3)The Center of Space Science & Applied Research, Chinese Academy of Science, Post Box8701, Beijing 100080, jkshi@@center.cssar.ac.cn (4) The Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Chilton, DIDCOT, Oxfordshire, OX11 0QX, UK, [email protected] (5)Space and Atmospheric Physics Group, Imperial College, London, [email protected] ABSTRACT transmitted straightforwardly from solar wind to the ionosphere (Bolshakova & Troitskaia, 1984). So far most Since launched in year 2000 the Cluster mission has research work on such topic are on basis of observation passed the region around the cusp at mid-altitude (~6Re) at ground or/and data from satellite located in the for many times, where ULF wave activities are rich in. upstream of solar wind or in the magnetosheath. To my From 0800 to 1300UT on October 30 2002 the Cluster knowledge, few authors take a study based on the spacecrafts ran along an orbit of southern cusp- measurement at the mid-altitude of the cusp. It seems plasmasphere-northern cusp that provides an excellent reasonable to assume that such a measurement be a direct observation of ULF waves in dayside magnetosphere. -

The Most Massive Star Cluster in the Local Group

This is a repository copy of A 'super' star cluster grown old: the most massive star cluster in the Local Group. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/144713/ Version: Published Version Article: Ma, J., De Grijs, R., Yang, Y. et al. (5 more authors) (2006) A 'super' star cluster grown old: the most massive star cluster in the Local Group. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society , 368 (3). pp. 1443-1450. ISSN 0035-8711 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10231.x This article has been accepted for publication in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society © 2006 The Authors. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Royal Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 368, 1443–1450 (2006) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10231.x A ‘super’ star cluster grown old: the most massive star cluster in the Local Group J. -

Planned Yet Uncontrolled Re-Entries of the Cluster-Ii Spacecraft

PLANNED YET UNCONTROLLED RE-ENTRIES OF THE CLUSTER-II SPACECRAFT Stijn Lemmens(1), Klaus Merz(1), Quirin Funke(1) , Benoit Bonvoisin(2), Stefan Löhle(3), Henrik Simon(1) (1) European Space Agency, Space Debris Office, Robert-Bosch-Straße 5, 64293 Darmstadt, Germany, Email:[email protected] (2) European Space Agency, Materials & Processes Section, Keplerlaan 1, 2201 AZ Noordwijk, Netherlands (3) Universität Stuttgart, Institut für Raumfahrtsysteme, Pfaffenwaldring 29, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany ABSTRACT investigate the physical connection between the Sun and Earth. Flying in a tetrahedral formation, the four After an in-depth mission analysis review the European spacecraft collect detailed data on small-scale changes Space Agency’s (ESA) four Cluster II spacecraft in near-Earth space and the interaction between the performed manoeuvres during 2015 aimed at ensuring a charged particles of the solar wind and Earth's re-entry for all of them between 2024 and 2027. This atmosphere. In order to explore the magnetosphere was done to contain any debris from the re-entry event Cluster II spacecraft occupy HEOs with initial near- to southern latitudes and hence minimise the risk for polar with orbital period of 57 hours at a perigee altitude people on ground, which was enabled by the relative of 19 000 km and apogee altitude of 119 000 km. The stability of the orbit under third body perturbations. four spacecraft have a cylindrical shape completed by Small differences in the highly eccentric orbits of the four long flagpole antennas. The diameter of the four spacecraft will lead to various different spacecraft is 2.9 m with a height of 1.3 m. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chapter 1 Introduction The magnetosheath lies between the bow shock and the magnetopause and is formed by the deflected, heated, and decelerated solar wind with a minor magnetospheric plasma component. The terrestrial magnetosheath field and flow structure have been extensively studied because they affect the transfer of mass, momentum, and energy between the solar wind and the Earth’s magnetosphere. When magnetic shear across the magnetopause is high and dayside reconnection is occurring, the coupling between the solar wind and the magnetosphere is substantially enhanced relative to periods when there is no reconnection [ Paschmann et al ., 1979; Sonnerup et al ., 1981]. The magnetosphere becomes energized leading to phenomena such as the aurora. When the terrestrial magnetosphere is closed, or when the solar wind dynamic pressure is sufficiently high, magnetic field lines pile up near the magnetopause forcing out the normally resident plasma leading to the formation of a plasma depletion layer. Because of the limited amount of available data, the Jovian magnetosheath has been less extensively studied than the Earth’s magnetosheath. Factors that control the size, shape, and rigidity of the magnetosheath are much different at Jupiter and the Earth. At Jupiter the solar wind dynamic pressure is down by more than an order of magnitude and the Alfvén Mach number is nearly double the mean values observed near Earth. Furthermore, at Jupiter the force balance at the magnetopause is not well approximated by balancing the contributions of the external solar wind dynamic pressure against the internal magnetic pressure. Magnetospheric energetic particles, thermal plasma, and dynamic pressure associated with the rapid rotation of Jupiter provide non-negligible contributions to the internal pressure [ Smith et al ., 1974]. -

ASTRONOMY and ASTROPHYSICS Seismology of Δ Scuti Stars in the Praesepe Cluster II

Astron. Astrophys. 338, 511–520 (1998) ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS Seismology of δ Scuti stars in the Praesepe cluster II. Identification of radial modes and their associated stellar parameters M.M. Hernandez´ 1?,F.Perez´ Hernandez´ 1, E. Michel2, J.A. Belmonte1, M.J. Goupil2, and Y. Lebreton2 1 Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Canarias, E-38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 2 DASGAL, URA CNRS 335, Observatoire de Paris, F-92195 Meudon, France Received 5 January 1998 / Accepted 20 July 1998 Abstract. An analysis based on a comparison between obser- Several attempts have been made to obtain stellar informa- vations and stellar models has been carried out to identify radial tion from δ Scuti stars (e.g. Mangeney et al. 1991; Goupil et modes of oscillations in several multi-periodic δ Scuti stars of al. 1993; Perez´ Hernandez´ et al. 1995; Guzik & Bradley 1995). the Praesepe cluster (BU, BN, BW and BS Cnc). The assump- All have had to face the absence of the greater part of the the- tion that all the stars considered have common parameters, such oretical modes in the observed spectrum. Noise level, selection as metallicity, distance or age, is imposed as a constraint. Even mechanisms, geometrical effects and also mutual interference so, there is a large number of possible solutions, partially caused between very close modes (as recently illustrated by Belmonte by the rotational effects on the pulsation frequencies and on the et al. 1997) contribute towards explaining this phenomenon. stars’ positions in the HR diagram, which need to be parame- Even in the case of a large number of detected modes, such as terized. -

The Ellipticities of Globular Clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy

ASTRONOMY & ASTROPHYSICS MAY I 1996, PAGE 447 SUPPLEMENT SERIES Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 116, 447-461 (1996) The ellipticities of globular clusters in the Andromeda galaxy A. Staneva1, N. Spassova2 and V. Golev1 1 Department of Astronomy, Faculty of Physics, St. Kliment Okhridski University of Sofia, 5 James Bourchier street, BG-1126 Sofia, Bulgaria 2 Institute of Astronomy, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 72 Tsarigradsko chauss´ee, BG-1784 Sofia, Bulgaria Received March 15; accepted October 4, 1995 Abstract. — The projected ellipticities and orientations of 173 globular clusters in the Andromeda galaxy have been determined by using isodensity contours and 2D Gaussian fitting techniques. A number of B plates taken with the 2 m Ritchey-Chretien-coud´e reflector of the Bulgarian National Astronomical Observatory were digitized and processed for each cluster. The derived ellipticities and orientations are presented in the form of a catalogue?. The projected ellipticities of M 31 GCs lie between 0.03 0.24 with mean valueε ¯=0.086 0.038. It may be concluded that the most globular clusters in the Andromeda galaxy÷ are quite spherical. The derived± orientations do not show a preference with respect to the center of M 31. Some correlations of the ellipticity with other clusters parameters are discussed. The ellipticities determined in this work are compared with those in other Local Group galaxies. Key words: globular clusters: general — galaxies: individual: M 31 — galaxies: star clusters — catalogs 1. Introduction Bergh & Morbey (1984), and Kontizas et al. (1989), have shown that the globulars in LMC are markedly more ellip- Representing the oldest of all stellar populations, the glo- tical than those in our Galaxy. -

European Space Agency Announces Contest to Name the Cluster Quartet

European Space Agency Announces Contest to Name the Cluster Quartet. 1. Contest rules The European Space Agency (ESA) is launching a public competition to find the most suitable names for its four Cluster II space weather satellites. The quartet, which are currently known as flight models 5, 6, 7 and 8, are scheduled for launch from Baikonur Space Centre in Kazakhstan in June and July 2000. Professor Roger Bonnet, ESA Director of Science Programme, announced the competition for the first time to the European Delegations on the occasion of the Science Programme Committee (SPC) meeting held in Paris on 21-22 February 2000. The competition is open to people of all the ESA member states. Each entry should include a set of FOUR names (places, people, or things from his- tory, mythology, or fiction, but NOT living persons). Contestants should also describe in a few sentences why their chosen names would be appropriate for the four Cluster II satellites. The winners will be those which are considered most suitable and relevant for the Cluster II mission. The names must not have been used before on space missions by ESA, other space organizations or individual countries. One winning entry per country will be selected to go to the Finals of the competition. The prize for each national winner will be an invitation to attend the first Cluster II launch event in mid-June 2000 with their family (4 persons) in a 3-day trip (including excursions to tourist sites) to one of these ESA establishments: ESRIN (near Rome, Italy): winners from France, Ireland, United King- dom, Belgium. -

Drilling Through the M31 Halo Near Mayall-II/G1

Drilling through the M31 Halo near Mayall-II/G1 Michael Gregg University of California, Davis Michael West Lowell Observatory Brian Lemaux University of California, Davis Andreas Küpper Quantco, Inc. Origin of the brightest Globulars Clusters Mayall-II/G1 in M31 Omega Cen in Milky Way •G1 has mass of ~107 M⊙ and σ = 25 km/s •High ellipticity, ~0.2, 50% rotationally supported •Metallicity spread, ~0.45 dex •Evidence for massive blackhole in the core, ~104 M⊙ •=> Former dwarf galaxy nucleus, now Ultra-Compact Dwarf? Origin of the brightest Globulars Clusters ...and connection to galaxy halo formation… HST image of nucleated Typical UCD (or bright globular) dwarf elliptical in in the same galaxy cluster: the Fornax galaxy cluster: possibly a tidally stripped nucleus nucleus + envelope of stars Origin of the brightest Globulars Clusters... Fornax Galaxy Cluster ...and connection to galaxy halo formation… image credit: M. Hilker •Evolved tidal streams are too faint (∼> 30 mag/sq.′′) to detect with standard imaging (Ibata et al. 2001; Ferguson et al. 2002; etc., etc., etc.) •Need resolved star spectroscopy to identify tidal debris; characteristics can perhaps can yield insight into the precursor of G1… G1 in Context Chemin et al. (2009) • We view G1 projected against the outer disk of M31, 2.6˚ (34 kpc) distant from the bulge. • The M31 disk has v < −500 km s-1 at G1 (Chemin et al. 2009). • G1 systemic v = −332 ± 3 km s-1 (Galleti et al. 2006), separation of ∼ 170 km s-1, 5-6 times the velocity dispersion of G1 or the M31 cold disk. -

Mayall II= G1 in M31: Giant Globular Cluster Or Core of a Dwarf Elliptical

Mayall II ≡ G1 in M31: Giant Globular Cluster or Core of a Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy? 1,2 G. Meylan3 Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, U.S.A., email: [email protected], and European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, D-85748 Garching bei M¨unchen, Germany. A. Sarajedini University of Florida, Astronomy Department, Gainesville, FL 32611-2055, U.S.A. email: [email protected]fl.edu P. Jablonka DAEC-URA 8631, Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, Place Jules Janssen, F-92195 Meudon, France. email: [email protected] S. G. Djorgovski Palomar Observatory, MS 105–24, Caltech, Pasadena, CA 91125, U.S.A. email: [email protected] T. Bridges Anglo-Australian Observatory, PO Box 296, Epping, NSW 2121, Australia. email: [email protected] R. M. Rich UCLA, Physics & Astronomy Department, Math-Sciences 8979, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1562, U.S.A. email: [email protected] 1 Based in part on observations made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, obtained at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-26555. These observations are associate with proposal IDs 5907 and 5464. arXiv:astro-ph/0105013v1 1 May 2001 2 Based in part on observations obtained at the W.M. Keck Observatory, which is operated jointly by the California Institute of Technology and the University of California. 3 Affiliated with the Astrophysics Division of the European Space Agency, ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands. ABSTRACT Mayall II ≡ G1 is one of the brightest globular clusters belonging to M31, the Andromeda galaxy. -

The 2011 Observers Challenge List

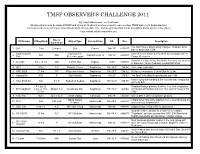

TMSP OBSERVER'S CHALLENGE 2011 By Kreig McBride and Tom Masterson All observations must be made at TMSP and 25 out of 30 objects must be viewed to earn a unique TMSP Observer's Award lapel pin. You must create a record of your observations which include date, time, instruments used and a brief description and/or sketch of the object. Your records will be returned to you. Size or ID Number V Magnitude Object Type Constellation RA Dec Description Separation The Sun! View 2 days noting changes. H-alpha, white 1 Sol -28m ½ degree Star Cancer 08h 39' +27d 07' light or projection is OK North Galactic Astronomical Catch this one before it sets. Next to the double star 31 2 N/A N/A Coma Berenices 12h 51' +27d 07' Pole Reference point Comae Berenices Omicron-2 a wide 4.9m, 9m double lies close by as does 3 U Cygni 5.9 – 12.1m N/A Carbon Star Cygnus 19.6h +47d 54' 6” diameter, 12.6m Planetary nebula NGC6884 4 M22 5.1m 7.8' Globular Cluster Sagittarius 18h 36.4' -23d 54' Rich, large and bright 5 NGC 6629 11.3m 15” Planetary Nebula Sagittarius 18h 25.7' -23d 12' Stellar at low powers. Central Star is 12.8m 6 Barnard 86 N/A 5' Dark Nebula Sagittarius 18h 03' -27d 53' “Ink Spot” Imbedded in spectacular star field Faint 1' glow surrounding 9.5m star w/a faint companion 7 NGC 6589-90 N/A 5' x 3' Reflection Nebula Sagittarius 18h 16.9'' -19d 47' 25” to its SW A 3.2m, B Reddish/Orange primary, B white, C is 10m companion 8 ETA Sagittarii 3.6m, C 10m, AB pair 3.6” Quadruple Star Sagittarius 18h 17.6' -36d 46' 93” distant at PA303d and D is 13m star 33” -

Globular Cluster Club

Globular Cluster Observing Club Raleigh Astronomy Club Version 1.2 22 June 2007 Introduction Welcome to the Globular Cluster Observing Club! This list is intended to give you an appreciation for the deep-sky objects known as globular clusters. There are 153 known Milky Way Globular Clusters of which the entire list can be found on the seds.org site listed below. To receive your Gold level we will only have you do sixty of them along with one challenge object from a list of three. Challenge objects being the extra-galactic globular Mayall II (G1) located in the Andromeda Galaxy, Palomar 4 in Ursa Major, and Omega Centauri a magnificent southern globular. The first two challenge your scope and viewing ability while Omega Centauri challenges your ability to plan for a southern view. A Silver level is also available and will be within the range of a 4 inch to 8 inch scope depending upon seeing conditions. Many of the objects are found in the Messier, Caldwell, or Herschel catalogs and can springboard you into those clubs. The list is meant for your viewing enrichment and edification of these types of clusters. It is also meant to enhance your viewing skills. You are encouraged to view the clusters with a critical eye toward the cluster’s size, visual magnitude, resolvability, concentration and colors. The Astronomical League’s Globular Clusters Club book “Guide to the Globular Cluster Observing Club” is an excellent resource for this endeavor. You will be asked to either sketch the cluster or give a short description of your visual impression, citing seeing conditions, time, date, cluster’s size, magnitude, resolvability, concentration, and any star colors. -

Formation of Giant Globular Cluster G1 and the Origin of the M 31 Stellar Halo

A&A 417, 437–442 (2004) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20034368 & c ESO 2004 Astrophysics Formation of giant globular cluster G1 and the origin of the M 31 stellar halo K. Bekki1 and M. Chiba2 1 School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Sydney 2052, Australia 2 Astronomical Institute, Tohoku University, Sendai, 980-8578, Japan e-mail: [email protected] Received 20 September 2003 / Accepted 21 October 2003 Abstract. We demonstrate that globular cluster G1 could have been formed by tidal interaction between M 31 and a nucleated dwarf galaxy (dE,N). Our fully self-consistent numerical simulations show that during tidal interaction between M 31 and G1’s 7 progenitor dE,N with MB ∼−15 mag and its nucleus mass of ∼10 M, the dark matter and the outer stellar envelope of the dE,N are nearly completely stripped whereas the nucleus can survive the tidal stripping because of its initially compact nature. The naked nucleus (i.e., G1) has orbital properties similar to those of its progenitor dE,N. The stripped stars form a metal-poor ([Fe/H] ∼−1) stellar halo around M 31 and its structure and kinematics depend strongly on the initial orbit of G1’s progenitor dE,N. We suggest that the observed large projected distance of G1 from M 31 (∼40 kpc) can give some strong constraints on the central density of the dark matter halo of dE,N. We discuss these results in the context of substructures of M 31’s stellar halo recently revealed by Ferguson et al.