Chapter 1 School Education in Luxembourg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everything You Need to Know About Luxembourg

Everything you need Everything you need toto know about knowLuxembourg about Luxembourg Luxembourg at a glance ATAt A a GLANCE glance Name Languages Official name: National language: Grand Duchy of Luxembourg luxembourgish (lëtzebuergesch) National holiday: Administrative languages: 23 June french, german and luxembourgish Geography Area: 2,586 sq. km Of which: agricultural: 49% wooded: 34% Neighbouring countries: Germany, Belgium and France Main towns: Luxembourg and Esch-sur-Alzette Administrative subdivisions: 3 districts (Luxembourg, Diekirch and Grevenmacher) 12 cantons, 118 town council areas (communes) Climate Temperate From May to mid-October, the temperatures are particu- larly pleasant. Whereas May and June are the sunniest months, July and August are the hottest. In September and October Luxembourg often experiences his own “Indian Summer”. Population Total population: 451,600 inhabitants, 81,800 of whom live in the City of Luxembourg. Over 174,200 (38.6%) people out of the total population are foreigners. (Source: STATEC January 2004) The capital City of Luxembourg Government Useful addresses : Form of government: Service information et presse du Gouvernement constitutional monarchy under a system of (Government Information and Press Service) parliamentary democracy 33, boulevard Roosevelt, L-2450 Luxembourg Head of State: Tel.: (+352) 478 21 81, Fax: (+352) 47 02 85 HRH Grand Duke Henri (since October 7, 2000) www.gouvernement.lu Head of government: www.luxembourg.lu Jean-Claude Juncker, Prime Minister [email protected] Parties in power in the government: coalition between the Christian-Social Party (CSV) Service central de la statistique et des études and the Socialist Workers’ Party of Luxembourg (LSAP) économiques (STATEC) Parties represented in the Chamber of Deputies: (Central Statistics and Economic Studies Service) Christian-Social Party (CSV), 13, rue Erasme, bâtiment Pierre Werner, Socialist Workers’ Party of Luxembourg (LSAP), B.P. -

Organisation of the Education System in Luxembourg 2009/2010

Organisation of the education system in Luxembourg 2009/2010 LU European Commission EURYBASE LUXEMBOURG TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND AND TRENDS 1.1 Historical overview 6 1.2 Main executive and legislative bodies 8 1.3 Religions 8 1.4 Official and minority languages 9 1.5 Demographic situation 10 1.6 Economic situation 12 1.7 Statistics 13 CHAPTER 2: ORGANISATION AND ADMINISTRATION 2.1 Historical overview 14 2.2 Ongoing debates and future developments 15 2.3 Fundamental principles and basic legislation 16 2.4 General structure and defining moments in educational guidance 16 2.5 Compulsory education 16 2.6 General administration 17 2.7 Internal and external consultation 20 2.8 Methods of financing education 23 2.9 Statistics 24 CHAPTER 3: CYCLE 1 OF THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (PREVIOUSLY: “EARLY AND PRE-SCHOOL EDUCATION”) 3.1 Historical overview 26 3.2 Ongoing debates and future developments 27 3.3 Specific legislative framework 30 3.4 General objectives 30 3.5 Geographical accessibility 32 3.6 Admission requirements and choice of institution/centre 33 3.7 Financial support for pupils’ families 35 3.8 Age levels and grouping of children 36 3.9 Organisation of time 36 3.10 Curriculum, types of activity, number of hours 37 3.11 Teaching methods and materials 38 3.12 Evaluation of children 40 3.13 Support facilities 40 3.14 Private sector provision 40 3.15 Organisational variations and alternative structures 41 3.16 Statistics 41 1 EURYBASE LUXEMBOURG CHAPTER 4 : PRIMARY EDUCATION 4.1 Historical overview 43 4.2 Ongoing debates and future developments 44 4.3 Specific legislative framework 45 4.4 General objectives 46 4.5 Geographical accessibility 46 4.6 Admission requirements and choice of school 47 4.7 Financial support for pupil’s families 47 4.8 Age levels and grouping of pupils 47 4.9 Organisation of school time 48 4.10 Curriculum, subjects, number of hours 49 4.11 Teaching methods and materials 51 4.12. -

Current Research on Multilingual and Multicultural Matters Master Class Symposium 2016

Current Research on Multilingual and Multicultural Matters Master Class Symposium 2016 When? 17.06.2016 from 13:15 to 19:00 Where? Campus Belval, Rooms: 4.050 / 4.160 / 4.530 Who? Master in Learning and Communication in Multilingual and Multicultural Contexts Topics include: Apprentissage / языки / öğretim / ﬕջմշակութային μάθηση / Edukacja / Identitate / 多种语刀 / Sienos / viacjazyčnosť aprendizagem / globalisaatio / การใ깉ความรู้ / Многоезичен / ال""""""""تّواص""""""""ل Migratioun / Etnografie / Investigación / міжнародний / 移住 / Kultur List of Absracts Evangelia Antoniou ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Promoting higher education institutions through social media: The creation of videos for the advertisement of the MA program Learning and Communication in Multilingual and Multicultural Contexts of the University of Luxembourg ............ Joanna Attridge ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Integration? A multilogical examination of the journey from Asylanten -'other' to Citizen - 'einer von uns'. .......................... Asmik Avagyan............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Armenian as a minority language in Moscow: language practices -

Biography of His Royal Highness the Grand Duke

Biography of His Royal Highness the Grand Duke His Royal Highness Grand Duke Henri was born on 16 April 1955 at Betzdorf Castle in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Grand Duke Henri, Prince of Nassau, Prince of Bourbon-Parma, is the eldest son of the five children of Grand Duke Jean and Grand Duchess Joséphine-Charlotte. On 14 February 1981, the Hereditary Grand Duke married Maria Teresa Mestre at the Cathédrale de Notre-Dame de Luxembourg. They have five children: • Prince Guillaume (born in 1981), the Hereditary Grand Duke, • Prince Félix (born in 1984), • Prince Louis (born in 1986), • Princess Alexandra (born in 1991) • Prince Sébastien (born in 1992). He became Head of State of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg on 7 October 2000. Preparing his role as future Head of State Prince Henri completed his secondary education in Luxembourg and France, where he passed his baccalaureate in 1974. He trained at the Royal Military Academy of Sandhurst in Great Britain and obtained the rank of officer in 1975. Prince Henri then enrolled at the Institut des hautes études internationales (Graduate Institute of International Studies) in Geneva, Switzerland, where he graduated with a Licence ès Sciences Politiques in 1980. Prince Henri met his future wife Maria Teresa Mestre during their university studies. Service Presse et Communication 1/7 In 1989, he was appointed Honorary Major of the Parachute Regiment in the United Kingdom. He also travelled extensively overseas to further his knowledge and education, particularly to the United States and Japan. As Hereditary Grand Duke, Prince Henri was an ex officio member of the Council of State from 1980 until 1998, which gave him insight into the legislative and institutional procedures and workings of the country. -

OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education LUXEMBOURG

OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education LUXEMBOURG How can student assessment, teacher appraisal, school evaluation and system evaluation bring about real gains in performance across a country’s school system? The country reports in this series provide, from an international perspective, an independent analysis of major issues facing the evaluation and assessment framework, current policy initiatives, and possible future approaches. This series forms part of the OECD Reviews of Evaluation OECD Review on Evaluation and Assessment Frameworks for Improving School Outcomes. and Assessment in Education Contents LUXEMBOURG Chapter 1. School education in Luxembourg Chapter 2. The evaluation and assessment framework Claire Shewbridge, Melanie Ehren, Chapter 3. Student assessment Paulo Santiago and Claudia Tamassia Chapter 4. Teacher appraisal Chapter 5. School evaluation Chapter 6. Education system evaluation AssessmentEducationand Evaluation in of Reviews OECD www.oecd.org/edu/evaluationpolicy LUXEMBOURG Please cite this publication as: Shewbridge, C., et al. (2012), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Luxembourg 2012, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264116801-en This work is published on the OECD iLibrary, which gathers all OECD books, periodicals and statistical databases. Visit www.oecd-ilibrary.org, and do not hesitate to contact us for more information. ISBN 978-92-64-11679-5 91 2011 25 1 P -:HSTCQE=VV[\^Z: OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Luxembourg 2012 Claire Shewbridge, Melanie Ehren, Paulo Santiago and Claudia Tamassia This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

Luxembourg Participation and Outcomes of Vocational Education

Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators is the authoritative source for information on the state of education around the world. It provides data on the structure, finances and performance of education systems in OECD and partner countries. Luxembourg Participation and outcomes of vocational education and training • Vocational education and training (VET) programmes attract a diverse range of students, including those seeking qualifications and technical skills to enter the labour market, adults wishing to increase their employability by developing their skills further, and students who may seek entry into higher education later on. • About one in three students from lower secondary to short-cycle tertiary level are enrolled in a VET programme on average across OECD countries. However, there are wide variations across countries, ranging from less than 20% of students enrolled in vocational education to more than 45% in a few countries. In Luxembourg, 35% of students are enrolled in vocational programmes, higher than the OECD average (32%), with the majority of lower secondary to short-cycle tertiary VET students (92%) found in upper secondary education (Figure 1). Figure 1. Snapshot of vocational education Note: Only countries and economies with available data are shown. The years shown in parentheses is the most common year of reference for OECD and partner countries. Refer to the source table for more details. Source: OECD (2020), indicator A3 and B7. See Education at a Glance Database. http://stats.oecd.org/ for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en). 2 | Luxembourg - Country Note • VET is an important part of upper secondary education in most OECD countries. -

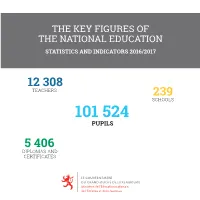

The Key Figures of the National Education Statistics and Indicators 2016/2017

THE KEY FIGURES OF THE NATIONAL EDUCATION STATISTICS AND INDICATORS 2016/2017 12 308 TEACHERS 239 SCHOOLS 101 524 PUPILS 5 406 DIPLOMAS AND CERTIFICATES THE KEY FIGURES OF THE NATIONAL EDUCATION STATISTICS AND INDICATORS 2016/2017 Ministry of National Education, Children and Youth Department of statistics and analysis Grand Duchy of Luxembourg 4 INTRODUCTION For the 16th consecutive year, the „Key Figures of National Education“ provides essential statistical indicators used as a basis for education policy-making, planning and follow-up of relevant national initiatives. Divided into eight chapters and annexes, the 2018 edition offers an overview of the education system in Luxembourg. As in the previous editions, the educational system in general is described at the beginning. This is then followed by the data for the school year 2016-2017, related to themes within the public schools and those private schools using the official national curriculum. The figures, texts, tables or charts provide trend data related to student enrolment by nationality and language spoken as well as the number of teachers. Other information include student attainment rates, number of schools and the costs and funding of the school system. A chapter provides an overview of the total pupils enrolled in Luxembourg, including those who attend a private or international school, whether or not teaching in those schools is based on the official national curriculum. Once again, this edition provides data to monitor the efforts to implement the national education priorities and to support decision-making. I hope that this publication remains a reference for statistics on education and as an objective basis underpinning debates on Luxembourg‘s system of education. -

Maastricht Global Education Declaration" 14

Global Education in Europe to 2015 Strategy, policies, and perspectives Outcomes and Papers of the Europe-wide Global Education Congress Maastricht, The Netherlands 15th-17 th November 2002 Editors Eddie O’Loughlin and Liam Wegimont Europe-wide Global Education Congress The Europe-wide Global Education Congress was held in Maastricht, the Netherlands, from 15th-17 th November 2002 and resulted in the adoption of the Maastricht Declaration on Global Education (see appendix 1). The Congress was organised by: North-South Centre of the Council of Europe In partnership with National Committee for International Cooperation and Sustainable Development, the Netherlands (NCDO); Government of Luxembourg; European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM); Learning for Sustainability; Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs; German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) Also supported by Austrian Development Cooperation; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sweden; OECD Development Centre; Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE) North-South Centre of the Council of Europe, Avenida da Liberdade, 229-4o, P-1250-142 Lisboa, Portugal. Tel.+351 21 3584030 Fax. +351 21 3584037 Website: www.nscentre.org www.globaleducationeurope.net This publication was possible in part thanks to the support of the European Commission within the framework of its contribution to the North-South Centre (A 3033/2003). North-South Centre of the Council of Europe, Lisbon, 2003 II CONTENTS Abbreviations 1 Preface 3 Introduction and Outline 5 PART 1 OUTCOMES OF THE MAASTRICHT CONGRESS 7 1.1 Executive Summary 9 1.2 Summary of the “Maastricht Global Education Declaration" 14 PART 2 GLOBAL EDUCATION IN EUROPE: CONTEXTS & PERSPECTIVES 15 2.1 INTRODUCTORY PAPERS 17 Global Education in Europe: Challenges and Opportunities 17 Bendik RUGAAS, Director General, DG IV - Education, Culture and Heritage, Youth and Sports, Council of Europe. -

Educational Trajectories Through Secondary Education in Luxembourg

Backes, Susanne; Hadjar, Andreas Educational trajectories through secondary education in Luxembourg: how does permeability affect educational inequalities? Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Bildungswissenschaften 39 (2017) 3, S. 437-460 Empfohlene Zitierung/ Suggested Citation: Backes, Susanne; Hadjar, Andreas: Educational trajectories through secondary education in Luxembourg: how does permeability affect educational inequalities? - In: Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Bildungswissenschaften 39 (2017) 3, S. 437-460 - URN: urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-166597 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-166597 in Kooperation mit / in cooperation with: http://www.rsse.ch/index.html Nutzungsbedingungen Terms of use Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, We grant a non-exclusive, non-transferable, individual and limited persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses right to using this document. Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für den This document is solely intended for your personal, non-commercial persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. Die use. Use of this document does not include any transfer of property Nutzung stellt keine Übertragung des Eigentumsrechts an diesem rights and it is conditional to the following limitations: All of the Dokument dar und gilt vorbehaltlich der folgenden copies of this documents must retain all copyright information and Einschränkungen: Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments other information regarding legal protection. You are not allowed to müssen alle Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf alter this document in any way, to copy it for public or commercial gesetzlichen Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, distribute or Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie otherwise use the document in public. -

Your Child at School

Your child at school Guide to Public Primary School Luxembourg City » Contents Your child at public primary school ....................................................................................................... p. 4 Public primary education framework ................................................................................................... p. 5 Cycles .................................................................................................................................................................................. p. 5 Subjects taught ............................................................................................................................................................ p. 5 Class schedules ........................................................................................................................................................... p. 6 School catchment areas ................................................................................................................................... p. 7 Nearby schools ............................................................................................................................................................. p. 7 Change of address during the school year ............................................................................................. p. 7 Enrolling your child ................................................................................................................................................ p. 8 Compulsory -

The Luxembourg Education System

2020 THE LUXEMBOURG EDUCATION SYSTEM 2020 THE LUXEMBOURG EDUCATION SYSTEM © Luxembourg Ministry of Education, Children and Youth., 2020 Service presse et communication isbn : 978-99959-1-267-3 web : www.men.lu Content A. Introduction ..............................................................................................................................6 B. Major themes ........................................................................................................................ 10 1. A global approach to the child ............................................................................................................................................................... 13 2. Reducing social inequalities ................................................................................................................................................................... 14 3. Multilingualism - an opportunity and a challenge ............................................................................................................................ 16 4. Different schools suited to different pupils ........................................................................................................................................ 18 5. The digitalisation of education .............................................................................................................................................................. 19 6. Development of quality assurance systems - a transversal priority ............................................................................................ -

Luxembourg a Perfectly Connected Host: European Cybersecurity Industrial, Technology and Research Competence Centre

Luxembourg A perfectly connected host: European Cybersecurity Industrial, Technology and Research Competence Centre Luxembourg – a perfectly connected host for the European Cybersecurity Competence Center Table of contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................. 3 A digital hub for the European Union: strong synergies through the proximity to the European Commission’s digital pole and to the EuroHPC ................................................. 5 Potential premises ............................................................................................................................ 6 A vibrant cybersecurity ecosystem ............................................................................................... 7 Excellent connectivity, security and interoperability with IT facilities........................... 10 Accessibility ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Excellent childcare and education in a naturally diverse and open system ................... 14 Labour market and healthcare .................................................................................................... 17 A safe environment ......................................................................................................................... 19 Quality of life ..................................................................................................................................