Maastricht Global Education Declaration" 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resume Kim Zwitserloot

Résumé Kim Zwitserloot Personal data: Surname: Zwitserloot First names: Kim Reinier Lucia Working experience: Sept 2014 – present University College Utrecht Member College Council Sept 2014 – present University College Utrecht Responsible for student recruitment in the UK Aug 2007 – present University College Utrecht Lecturer in economics and Tutor (Student Counsellor/Academic Advisor) Aug 2009 – Aug 2014 University College Utrecht Recruitment officer, responsible for international marketing Aug 2007 – 2009 Utrecht School of Economics Lecturer and course coordinator Aug 2005-Aug 2007 University of Maastricht and Faculty of Economics and Business Administration (FEBA) 2004, Oct-Dec Function: Lecturer and course coordinator 2005, Jan-June Inlingua Venezuela/AIESEC Caracas, Venezuela Teacher of English, clients were employees of MNCs Commissioner Internal Affairs, responsible for organisation of social activities Education: 1999-2004 Maastricht University Faculty of Economics and Business Administration (FEBA) International Economic Studies, MSc Master thesis: Getting what you want in Brussels, NGOs and Public Affairs Management in the EU Supervisor: Prof. Dr. J.G.A. van Mierlo 2003, Jan-June Tecnológico de Monterrey, Mexico City, Mexico Exchange student 1993-1999 St-Janscollege, Hoensbroek Gymnasium Dutch, English, German, Latin, General economics, Accounting, Standard level and higher level mathematics (Wiskunde A and B) Voluntary work 2002-2007 AEGEE-Academy1 Trainer and participant in several training courses concerning project management, -

1 Abstract: the Ratification of the Maastricht Treaty Caused Significant

Abstract: The ratification of the Maastricht Treaty caused significant ratification problems for a series of national governments. The product of a new intergovernmental conference, namely the Amsterdam Treaty, has caused fewer problems, as the successful national ratifications have demonstrated. Employing the two-level concept of international bargains, we provide a thorough analysis of these successful ratifications. Drawing on datasets covering the positions of the negotiating national governments and the national political parties we highlight the differences in the Amsterdam ratification procedures in all fifteen European Union members states. This analysis allows us to characterize the varying ratification difficulties in each state from a comparative perspective. Moreover, the empirical analysis shows that member states excluded half of the Amsterdam bargaining issues to secure a smooth ratification. Issue subtraction can be explained by the extent to which the negotiators were constrained by domestics interests, since member states with higher domestic ratification constraints performed better in eliminating uncomfortable issues at Intergovernmental Conferences. 1 Simon Hug, Department of Government ; University of Texas at Austin ; Burdine 564 ; Austin TX 78712-1087; USA; Fax: ++ 1 512 471 1067; Phone: ++ 1 512 232 7273; email: [email protected] Thomas König, Department of Politics and Management; University of Konstanz; Universitätsstrasse 10; D-78457 Konstanz; Fax: ++ 49 (0) 7531 88-4103; Phone: ++ (0) 7531 88-2611; email: [email protected]. 2 (First version: August 2, 1999, this version: December 4, 2000) Number of words: 13086 3 An earlier version of this paper was prepared for presentation at the Annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Atlanta, September 2-5, 1999. -

Culture at a First Glance Is Published by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science

... Contents Section 1 Introduction 7 Section 2 General Outline 9 2.1 Geography and language 9 2.2 Population and demographics 9 2.3 The role of the city 11 2.4 Organisation of government 13 2.5 Politics and society 14 2.6 Economic and social trends 15 Section 3 Cultural Policy 19 3.1 Historical perspective 19 3.2 Division of roles in tiers of government in funding of culture 20 3.3 Government spending on culture 21 3.3.1 Central government’s culture budget for 2013-2016 21 3.3.2 Municipal spending on culture 22 3.3.3 Impact of cuts on funded institutions 25 3.4 Cultural amenities: spread 26 3.5 Priority areas for the Dutch government 29 3.5.1 Cultural education and participation in cultural life 29 3.5.2 Talent development 30 3.5.3 The creative industries 30 3.5.4 Digitisation 31 3.5.5 Entrepreneurship 31 3.5.6 Internationalisation, regionalisation and urbanisation 32 3.6 Funding system 33 3.7 The national cultural funds 34 3.8 Cultural heritage 35 3.9 Media policy 38 Section 4 Trends in the culture sector 41 4.1 Financial trends 41 4.2 Trends in offering and visits 2009-2014 44 4.2.1 Size of the culture sector 44 4.2.2 Matthew effects? 45 4.3 Cultural reach 45 4.3.1 More frequent visits to popular performances 47 4.3.2 Reach of the visual arts 47 4.3.3 Interest in Dutch arts abroad 51 4.3.4 Cultural tourism 53 4.3.5 Culture via the media and internet 54 4.4 Arts and heritage practice 57 4.5 Cultural education 59 5 1 Introduction Culture at a first Glance is published by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. -

The Hague District Court

THE HAGUE DISTRICT COURT Chamber for Commercial Affairs case number / cause list number: C/09/456689 / HA ZA 13-1396 Judgment of 24 June 2015 in the case of the foundation URGENDA FOUNDATION, acting on its own behalf as well as in its capacity as representative ad litem and representative of the individuals included in the list attached to the summons, with its registered office and principal place of business in Amsterdam, claimant, lawyers mr.1R.H.J. Cox of Maastricht and mr. J.M. van den Berg of Amsterdam, versus the legal person under public law THE STATE OF THE NETHERLANDS (MINISTRY OF INFRASTRUCTURE AND THE ENVIRONMENT), seated in The Hague, defendant, lawyers mr. G.J.H. Houtzagers of The Hague and mr. E.H.P. Brans of The Hague. Parties are hereinafter referred to as Urgenda and the State. (Translation) Only the Dutch text of the ruling is authoratative. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1THE PROCEEDINGS 1 2 THE FACTS 2 A. The Parties 2.1 B. Reasons for these proceedings 2.6 C. Scientific organisations and publications 2.8 IPCC 2.8 AR4/2007 2.12 AR5/2013 2.18 PBL and KNMI 2.22 EDGAR 2.25 UNEP 2.29 D. Climate change and the development of legal and policy frameworks 2.34 In a UN context 2.35 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change 1992 2.35 Kyoto Protocol 1997 and Doha Amendment 2012 2.42 Climate change conferences (Conference of the Parties - COP) 2.47 a) Bali Action Plan 2007 2.48 b) The Cancun Agreements 2010 2.49 c) Durban 2011 2.51 In a European context 2.53 In a national context 2.69 3THE DISPUTE 3 4 THE ASSESSMENT 4 A. -

Everything You Need to Know About Luxembourg

Everything you need Everything you need toto know about knowLuxembourg about Luxembourg Luxembourg at a glance ATAt A a GLANCE glance Name Languages Official name: National language: Grand Duchy of Luxembourg luxembourgish (lëtzebuergesch) National holiday: Administrative languages: 23 June french, german and luxembourgish Geography Area: 2,586 sq. km Of which: agricultural: 49% wooded: 34% Neighbouring countries: Germany, Belgium and France Main towns: Luxembourg and Esch-sur-Alzette Administrative subdivisions: 3 districts (Luxembourg, Diekirch and Grevenmacher) 12 cantons, 118 town council areas (communes) Climate Temperate From May to mid-October, the temperatures are particu- larly pleasant. Whereas May and June are the sunniest months, July and August are the hottest. In September and October Luxembourg often experiences his own “Indian Summer”. Population Total population: 451,600 inhabitants, 81,800 of whom live in the City of Luxembourg. Over 174,200 (38.6%) people out of the total population are foreigners. (Source: STATEC January 2004) The capital City of Luxembourg Government Useful addresses : Form of government: Service information et presse du Gouvernement constitutional monarchy under a system of (Government Information and Press Service) parliamentary democracy 33, boulevard Roosevelt, L-2450 Luxembourg Head of State: Tel.: (+352) 478 21 81, Fax: (+352) 47 02 85 HRH Grand Duke Henri (since October 7, 2000) www.gouvernement.lu Head of government: www.luxembourg.lu Jean-Claude Juncker, Prime Minister [email protected] Parties in power in the government: coalition between the Christian-Social Party (CSV) Service central de la statistique et des études and the Socialist Workers’ Party of Luxembourg (LSAP) économiques (STATEC) Parties represented in the Chamber of Deputies: (Central Statistics and Economic Studies Service) Christian-Social Party (CSV), 13, rue Erasme, bâtiment Pierre Werner, Socialist Workers’ Party of Luxembourg (LSAP), B.P. -

Hotel Accommodations

Dear Participant, For the upcoming conference, Migration: A World in Motion A Multinational Conference on Migration and Migration Policy 18-20 February 2010 Maastricht, the Netherlands We have made a short list of preferable hotels in the inner-city of Maastricht. In order to help you find accommodation during your stay in Maastricht, we have arranged a number of options at various preferable hotels in the city. Please not that it is your own responsibility to make reservations and get in contact with the applicable hotel. The hotels will ask you to indicate your dietary and special needs, in order to make your stay as comfortable as possible. Moreover, the hotels will also need your credit card details, in order to guarantee the booking. For further information, please contact the hotel directly. They also want you to mention the following code while making reservations so they know that your booking is within regards to the APPAM conference. Without mentioning this code you won’t be able to book a room for a special arranged price! Please use the following code in your reservation: APPAM_2010 You can choose from the following hotels. Please note that the available rooms will be booked on a “first-come-first-serve”basis. Derlon Hotel Maastricht 1. Special price for APPAM participants; €135,- per room, per night, including breakfast; 2. Reservations made before November 1st 2009 will get a €2,50 discount per person, per stay; 3. Deluxe Hotel; 4. Directly located in the city centre of Maastricht, at 5 minutes walk from the Maastricht Graduate School of Governance, situated at one of the most beautiful squares in the Netherlands: the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Plein; 5. -

Organisation of the Education System in Luxembourg 2009/2010

Organisation of the education system in Luxembourg 2009/2010 LU European Commission EURYBASE LUXEMBOURG TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND AND TRENDS 1.1 Historical overview 6 1.2 Main executive and legislative bodies 8 1.3 Religions 8 1.4 Official and minority languages 9 1.5 Demographic situation 10 1.6 Economic situation 12 1.7 Statistics 13 CHAPTER 2: ORGANISATION AND ADMINISTRATION 2.1 Historical overview 14 2.2 Ongoing debates and future developments 15 2.3 Fundamental principles and basic legislation 16 2.4 General structure and defining moments in educational guidance 16 2.5 Compulsory education 16 2.6 General administration 17 2.7 Internal and external consultation 20 2.8 Methods of financing education 23 2.9 Statistics 24 CHAPTER 3: CYCLE 1 OF THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (PREVIOUSLY: “EARLY AND PRE-SCHOOL EDUCATION”) 3.1 Historical overview 26 3.2 Ongoing debates and future developments 27 3.3 Specific legislative framework 30 3.4 General objectives 30 3.5 Geographical accessibility 32 3.6 Admission requirements and choice of institution/centre 33 3.7 Financial support for pupils’ families 35 3.8 Age levels and grouping of children 36 3.9 Organisation of time 36 3.10 Curriculum, types of activity, number of hours 37 3.11 Teaching methods and materials 38 3.12 Evaluation of children 40 3.13 Support facilities 40 3.14 Private sector provision 40 3.15 Organisational variations and alternative structures 41 3.16 Statistics 41 1 EURYBASE LUXEMBOURG CHAPTER 4 : PRIMARY EDUCATION 4.1 Historical overview 43 4.2 Ongoing debates and future developments 44 4.3 Specific legislative framework 45 4.4 General objectives 46 4.5 Geographical accessibility 46 4.6 Admission requirements and choice of school 47 4.7 Financial support for pupil’s families 47 4.8 Age levels and grouping of pupils 47 4.9 Organisation of school time 48 4.10 Curriculum, subjects, number of hours 49 4.11 Teaching methods and materials 51 4.12. -

Connexion Q2 2019

Photo’s Copywrite: © Cour grand-ducale / Jochen Herling the New GRAND DUKE JEAN Q2 - 2019 4€ GRAND DUKE JEAN © Collections de la Cour grand-ducale MERCI PAPA Mon Père Mes chers concitoyens En ce jour de funérailles de notre cher Père, j’aimerais vous dire combien il a compté pour nous tous, ses enfants, belles-filles et gendres, petits-enfants et arrière-petits-enfants. Toute sa vie durant, il est resté très attentif à sa famille, malgré la lourde charge qu’il accomplissait avec sagesse et un grand sens du devoir. Il pouvait aussi compter sur le soutien précieux de son épouse, ma mère, la Grande-Duchesse Joséphine-Charlotte. Tourné vers les autres, il avait cette faculté d’écoute exceptionnelle qui touchait chaque personne qu’il rencontrait. C’était une personne au caractère éminemment positif. Curieux de tout, il participait quelques jours encore avant son hospitalisation au Forum organisé par mon épouse ou visitait une exposition. Il suivait tout ce qui se passait dans le pays. Même l’épineux dossier du “Brexit” n’avait que peu de secrets pour lui. Je suis persuadé que cette disposition d’esprit et sa vivacité ont été les garants de sa longévité. Dans son cercle plus intime, sa joie de vivre rayonnait sur nous tous et son sens de l’humour nous faisait parfois rire aux larmes. Il était d’un soutien constant, en nous encourageant et en nous félicitant dans nos actions, tout en respectant entièrement nos choix et nos décisions. Bien sûr, l’autre ambition de sa vie fut l’amour profond qu’il portait à sa patrie et la très grande affection qu’il vouait à ses compatriotes dans leur unité et leur diversité. -

Joint Letter on the Medical Treatment of Prisoners in Bahrain

H.E. the Head of the European Union Delegation to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the Kingdom of Bahrain and the Sultanate of Oman Ambassador Michele Cervone d’Urso Brussels, 21 November 2019 Dear Ambassador Cervone d’Urso, We, the undersigned Members of the European Parliament, are writing to express our concerns about the cruel and inhumane treatment of several high-profile prisoners in Bahrain, and to ask that you urge the Bahraini authorities to immediately allow those prisoners access to adequate medical care. Human rights organisations and family members of the prisoners, whose detention is at least questionable in the first place, have reported that prison authorities are arbitrarily denying prisoners urgent medical care, refusing to refer them to specialists, failing to disclose medical examination results, and withholding medication as a form of punishment. Denying a prisoner needed medical care violates the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, known as the Mandela Rules. Jau Prison Medical negligence, delays, and arbitrary exercise of authority in Bahrain’s prison system have been well-documented by the international human rights community. According to Amnesty International, in many cases, this has escalated to the level of intentional ill-treatment and permanent damage to the health of individuals suffering from injuries or grave chronic illnesses. The cases of political leader Hassan Mushaima, 71, and academic and opposition figure Dr. Abduljalil Al-Singace, 57, are especially alarming. Both men have been arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment in relation to their peaceful role in the 2011 pro-democracy movement. Dr. Al-Singace has experienced abuse and torture while in prison, documented by several human rights organisations. -

Uef-Spinelli Group

UEF-SPINELLI GROUP MANIFESTO 9 MAY 2021 At watershed moments in history, communities need to adapt their institutions to avoid sliding into irreversible decline, thus equipping themselves to govern new circumstances. After the end of the Cold War the European Union, with the creation of the monetary Union, took a first crucial step towards adapting its institutions; but it was unable to agree on a true fiscal and social policy for the Euro. Later, the Lisbon Treaty strengthened the legislative role of the European Parliament, but again failed to create a strong economic and political union in order to complete the Euro. Resulting from that, the EU was not equipped to react effectively to the first major challenges and crises of the XXI century: the financial crash of 2008, the migration flows of 2015- 2016, the rise of national populism, and the 2016 Brexit referendum. This failure also resulted in a strengthening of the role of national governments — as shown, for example, by the current excessive concentration of power within the European Council, whose actions are blocked by opposing national vetoes —, and in the EU’s chronic inability to develop a common foreign policy capable of promoting Europe’s common strategic interests. Now, however, the tune has changed. In the face of an unprecedented public health crisis and the corresponding collapse of its economies, Europe has reacted with unity and resolve, indicating the way forward for the future of European integration: it laid the foundations by starting with an unprecedented common vaccination strategy, for a “Europe of Health”, and unveiled a recovery plan which will be financed by shared borrowing and repaid by revenue from new EU taxes levied on the digital and financial giants and on polluting industries. -

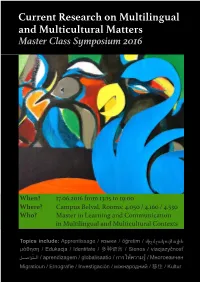

Current Research on Multilingual and Multicultural Matters Master Class Symposium 2016

Current Research on Multilingual and Multicultural Matters Master Class Symposium 2016 When? 17.06.2016 from 13:15 to 19:00 Where? Campus Belval, Rooms: 4.050 / 4.160 / 4.530 Who? Master in Learning and Communication in Multilingual and Multicultural Contexts Topics include: Apprentissage / языки / öğretim / ﬕջմշակութային μάθηση / Edukacja / Identitate / 多种语刀 / Sienos / viacjazyčnosť aprendizagem / globalisaatio / การใ깉ความรู้ / Многоезичен / ال""""""""تّواص""""""""ل Migratioun / Etnografie / Investigación / міжнародний / 移住 / Kultur List of Absracts Evangelia Antoniou ...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Promoting higher education institutions through social media: The creation of videos for the advertisement of the MA program Learning and Communication in Multilingual and Multicultural Contexts of the University of Luxembourg ............ Joanna Attridge ............................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Integration? A multilogical examination of the journey from Asylanten -'other' to Citizen - 'einer von uns'. .......................... Asmik Avagyan............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Armenian as a minority language in Moscow: language practices -

Ms Ursula Von Der Leyen, President of the European Commission European Commission Rue De La Loi/Wetstraat 200 1049 Brussels

Ms Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission European Commission Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat 200 1049 Brussels Mr Charles Michel, President of the European Council European Commission Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat 175 1049 Brussels Brussels, 27 July 2020 Dear President von der Leyen, Dear President Michel, With this letter, we would like to draw your attention to the Polish government’s expressed intent to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention on fighting domestic violence. This latest development shows that we can never take women’s rights for granted. This is disrespectful, a clear violation of women’s rights and unacceptable. The signal the Polish government is sending is a highly troubling one in times that are already challenging for women. Women have been hit disproportionally hard by the Covid-19 crisis and face an increase in cases of domestic violence. The European Union is founded upon shared values that are enshrined in our Treaties, amongst them equality between men and women. We cannot regress on these core values stipulated in Article 2 TEU. We should never accept it when one of our Member States backtracks from equality. That is why we call on you, as the President of the European Commission, guardian of the treaties, and as the President of the European Council, to do everything within your power to discourage the Polish government from taking this misstep. Madam President, in your political guidelines, you made the commitment that the EU’s accession to the Istanbul Convention is a key priority for the Commission and that if the accession remains blocked in the Council, you would consider tabling proposals on minimum standards regarding the definition of certain types of violence, and strengthening the Victims’ Rights Directive.