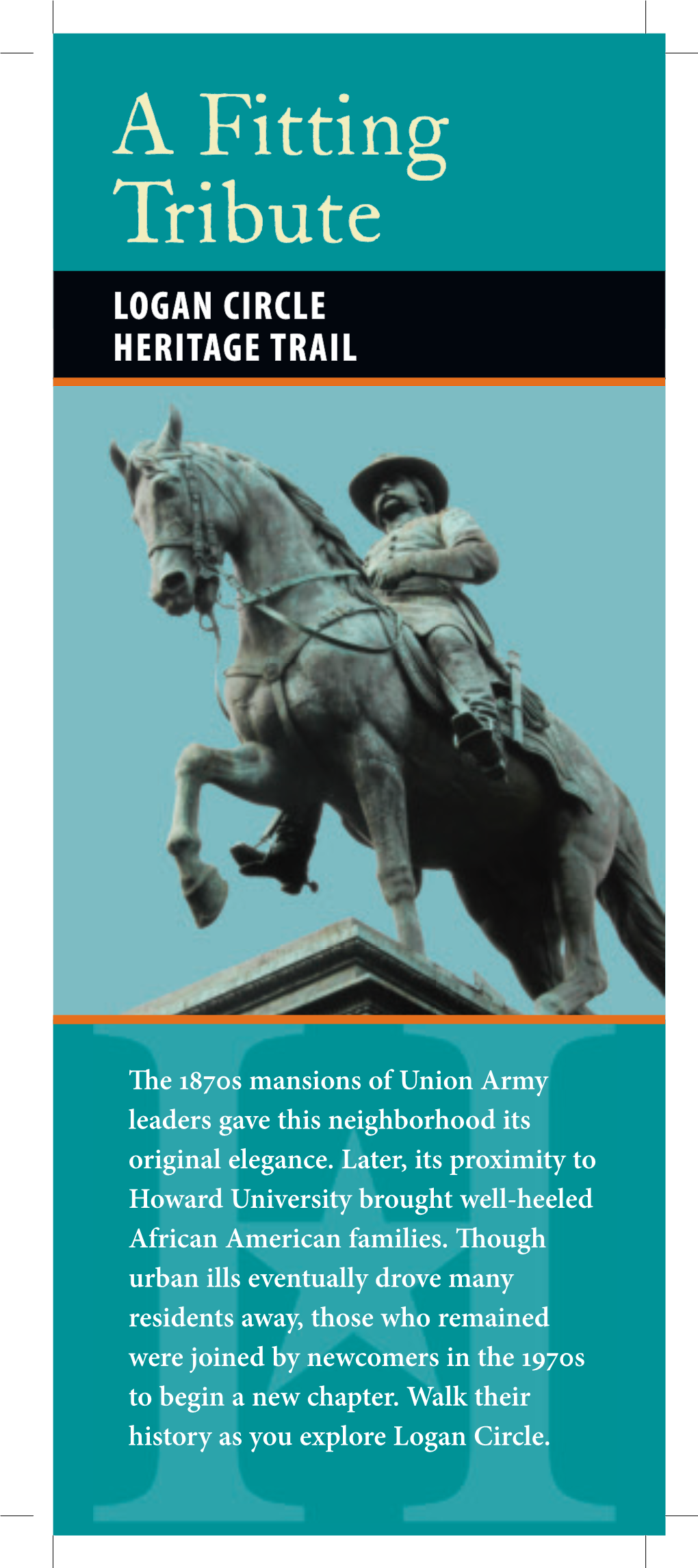

Logan Circle Heritage Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southeast Museum of Photography Preservation Assessment Project

PG-266669-19 Southeast Museum of Photography Preservation Assessment Project A. What activity or activities would the grant support? Support will fund three primary activities for the Southeast Museum of Photography Preservation Assessment Project: • A formal assessment of the photographs and photographic objects from the museum’s 4,500 piece collection, by a professional conservator of photographs. • In consultation with a professional conservator of photographs, the creation of a long-term preservation strategy for existing materials and future accessions. • In consultation with a professional conservator of photographs, the creation of a list of appropriate archival collections materials to reinforce existing collection materials and to support the care of future acquisitions. Through these activities, the Southeast Museum of Photography (SMP) aims to become better stewards of its cultural artifacts, ensuring the photographs and photographic materials in the museum’s care can be preserved and maintained in accordance with the highest of collections standards for future generations of researchers, educators, and museum visitors. B. What are the content and size of the humanities collections that are the focus of the project? The Museum houses 4,500 photographs dating from the mid-19th century to the present, 1,500 objects representing photographic processes such as photo transfer screen prints, photogravure prints, glass lantern slides, and 372 vintage or antique cameras. The photographic collection of SMP includes representatives from every major photographic process and the developments within those processes, including: tintypes, daguerreotypes, albumen prints, cyanotypes, gelatin silver prints, and C-prints. Highlights of the collection include: • Vintage and authorized edition prints from modern photography masters including: o Edward Weston: one of the foremost champions of highly detailed photographic images and the first American to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship. -

Village in the City Historic Markers Lead You To: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail – a Pre-Civil War Country Estate

On this self-guided walking tour of Mount Pleasant, Village in the City historic markers lead you to: MOUNT PLEASANT HERITAGE TRAIL – A pre-Civil War country estate. – Homes of musicians Jimmy Dean, Bo Diddley and Charlie Waller. – Senators pitcher Walter Johnson's elegant apartment house. – The church where civil rights activist H. Rap Brown spoke in 1967. – Mount Pleasant's first bodega. – Graceful mansions. – The first African American church on 16th Street. – The path President Teddy Roosevelt took to skinny-dip in Rock Creek Park. Originally a bucolic country village, Mount Pleasant has been a fashion- able streetcar suburb, working-class and immigrant neighborhood, Latino barrio, and hub of arts and activism. Follow this trail to discover the traces left by each succeeding generation and how they add up to an urban place that still feels like a village. Welcome. Visitors to Washington, DC flock to the National Mall, where grand monuments symbolize the nation’s highest ideals. This self-guided walking tour is the seventh in a series that invites you to discover what lies beyond the monuments: Washington’s historic neighborhoods. Founded just after the Civil War, bucolic Mount Pleasant village was home to some of the city’s movers and shakers. Then, as the city grew around it, the village evolved by turn into a fashionable streetcar suburb, a working-class neigh- borhood, a haven for immigrants fleeing political turmoil, a sometimes gritty inner-city area, and the heart of DC’s Latino community. This guide, summariz- ing the 17 signs of Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail, leads you to the sites where history lives. -

Joint Force Quarterly 97

Issue 97, 2nd Quarter 2020 JOINT FORCE QUARTERLY Broadening Traditional Domains Commercial Satellites and National Security Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy ISSUE NINETY-SEVEN, 2 ISSUE NINETY-SEVEN, ND QUARTER 2020 Joint Force Quarterly Founded in 1993 • Vol. 97, 2nd Quarter 2020 https://ndupress.ndu.edu GEN Mark A. Milley, USA, Publisher VADM Frederick J. Roegge, USN, President, NDU Editor in Chief Col William T. Eliason, USAF (Ret.), Ph.D. Executive Editor Jeffrey D. Smotherman, Ph.D. Production Editor John J. Church, D.M.A. Internet Publications Editor Joanna E. Seich Copyeditor Andrea L. Connell Associate Editor Jack Godwin, Ph.D. Book Review Editor Brett Swaney Art Director Marco Marchegiani, U.S. Government Publishing Office Advisory Committee Ambassador Erica Barks-Ruggles/College of International Security Affairs; RDML Shoshana S. Chatfield, USN/U.S. Naval War College; Col Thomas J. Gordon, USMC/Marine Corps Command and Staff College; MG Lewis G. Irwin, USAR/Joint Forces Staff College; MG John S. Kem, USA/U.S. Army War College; Cassandra C. Lewis, Ph.D./College of Information and Cyberspace; LTG Michael D. Lundy, USA/U.S. Army Command and General Staff College; LtGen Daniel J. O’Donohue, USMC/The Joint Staff; Brig Gen Evan L. Pettus, USAF/Air Command and Staff College; RDML Cedric E. Pringle, USN/National War College; Brig Gen Kyle W. Robinson, USAF/Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy; Brig Gen Jeremy T. Sloane, USAF/Air War College; Col Blair J. Sokol, USMC/Marine Corps War College; Lt Gen Glen D. VanHerck, USAF/The Joint Staff Editorial Board Richard K. -

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

Download the Contributor's Manual

Oxford University Press Hutchins Center for African &African American Research at Harvard University CONTRIBUTOR’S MANUAL African American National Biography Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham Editors in Chief http://hutchinscenter.fas.harvard.edu/aanb CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 2 PLANNING YOUR ARTICLE 2.1 Readership 2.2 Scope Description 2.3 Word Allotment 2.4 Consensus of Interpretation 3 WRITING YOUR ARTICLE 3.1 Opening Paragraph 3.2 Body of Text 3.3 Marriages 3.4 Death and Summation 3.5 Living People 3.6 Identifying People, Places and Things 3.7 Dates 3.8 Quotations and Permissions 3.9 Citations 3.10 Plagiarism 4 SOME NOTES ON STYLE 4.1 Style, Grammar, spelling 4.2 Spelling 4.3 Punctuation 4.4 Capitalization 4.5 Dates 4.6 Racial Terminology 4.7 Explicit Racial Identification 4.8 Gendered Terms 5 COMPILING YOUR “FURTHER READING” BIBLIOGRAPHY 5.1 Purpose 5.2 Number of Items 5.3 Availability of Works 5.4 Format 5.5 Verification of Sources 6 KEYBOARDING AND SUBMITTING YOUR MANUSCRIPT 1 1 INTRODUCTION We very much appreciate your willingness to contribute to the African American National Biography (AANB). More than a decade in the making, the AANB is now in its second edition, bringing the total number of lives profiled to nearly 5,000 entries online and in print. Our approximately 2,000 authors include Darlene Clark Hine on First Lady Barack Obama, John Swed on Miles Davis; Thomas Holt on W.E.B. Du Bois and the late John Hope Franklin on the pioneering black historian George Washington Williams. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

Appendix C Evolution of Arts Uses in the Arts Overlay Zone

Appendix C Evolution of Arts Uses in the Arts Overlay Zone A short (and incomplete) history of the arts on 14 th and U Streets While there has been a significant amount of research and writing about the “Black Broadway” of U Street during the early part of the 20 th century, less information is available about the renaissance of arts and arts institutions in the neighborhood since the riots of 1968, and why the neighborhood can claim as many arts institutions as it does. This is a first attempt to put together a history of the theatric, visual, and musical arts as these institutions appear at the end of the first decade of the 21 st century, and is not meant to serve as a comprehensive review. A more thorough study of the history of arts in the community needs to be undertaken in order to capture a complete picture. In addition, much of the history is due to the initiative and accomplishments of a few key individuals, and those people each deserve to tell their story in their own words. As the arts district continues to develop, it will be important to return to this document and expand upon it to better appreciate why arts institutions are among us, how they have been able to sustain, and what can be done to encourage their longevity and growth in the decades to come. Theatres and theatrical groups The riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King left 14 th and U Streets largely intact, but scarred. Merchants used metal grates and sliding garage-style barriers to close their businesses at the end of the day. -

What Art Defined the Civil Rights Era? We Asked 7 Museum Curators to Pick One Work That Crystallized the Moment

Art World What Art Defined the Civil Rights Era? We Asked 7 Museum Curators to Pick One Work That Crystallized the Moment Curators from across the country share the works that capture the ethos of the era. Katie White (https://news.artnet.com/about/katie-white-1066), January 20, 2020 Gordon Parks, Department Store (1956). Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation. In honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we tasked curators across the country with the difficult task of choosing a single work of art that they feel defines the ethos of the Civil Rights Era. Their choices present a kaleidoscopic and occasionally surprising group of works that span continents and centuries—from iconic photographs to ritual sculptural objects. See the works and read the curators’ insights below. Joe Minter’s Children In Jail (2013) Joe Minter, Children In Jail (2013). Courtesy of Souls Grown Deep. This contemporary work by Joe Minter reflects back on Birmingham, Alabama’s Children’s Crusade: On May 2, 1963, more than 1,000 students skipped school and took to the streets from the doors of the 16th Street Baptist Church, and for days faced police violence and dog attacks, brutal sprays of fire hoses, and mass arrests. Ultimately, more than 3,000 children took part in the direct actions. More than 500 children were jailed by Alabama Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor, including 75 kids crammed into a cell meant for eight adults, and still others locked into animal pens at the fairgrounds for days on end. Thanks to their sacrifices and the widespread media images of brutalized black children, President Kennedy took notice, the city negotiated with Martin Luther King Jr., jailed demonstrators were freed, and Connor lost his job. -

Individual Projects

PROJECTS COMPLETED BY PROLOGUE DC HISTORIANS Mara Cherkasky This Place Has A Voice, Canal Park public art project, consulting historian, http://www.thisplacehasavoice.info The Hotel Harrington: A Witness to Washington DC's History Since 1914 (brochure, 2014) An East-of-the-River View: Anacostia Heritage Trail (Cultural Tourism DC, 2014) Remembering Georgetown's Streetcar Era: The O and P Streets Rehabilitation Project (exhibit panels and booklet documenting the District Department of Transportation's award-winning streetcar and pavement-preservation project, 2013) The Public Service Commission of the District of Columbia: The First 100 Years (exhibit panels and PowerPoint presentations, 2013) Historic Park View: A Walking Tour (booklet, Park View United Neighborhood Coalition, 2012) DC Neighborhood Heritage Trail booklets: Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail (2006); Battleground to Community: Brightwood Heritage Trail (2008); A Self-Reliant People: Greater Deanwood Heritage Trail (2009); Cultural Convergence: Columbia Heights Heritage Trail (2009); Top of the Town: Tenleytown Heritage Trail (2010); Civil War to Civil Rights: Downtown Heritage Trail (2011); Lift Every Voice: Georgia Avenue/Pleasant Plains Heritage Trail (2011); Hub, Home, Heart: H Street NE Heritage Trail (2012); and Make No Little Plans: Federal Triangle Heritage Trail (2012) “Mount Pleasant,” in Washington at Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation's Capital (Kathryn Schneider Smith, editor, Johns Hopkins Press, 2010) Mount -

Draft Development Framework for a Cultural Destination District Within Washington, Dc’S Greater Shaw / U Street 2

DUKE Government of the District of Columbia DC Office of Planning DRAFT DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK Assisted by Bay Area Economics FOR A CULTURAL DESTINATION DISTRICT Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Kuhn Stanmore Associates PETR Productions WITHIN WASHINGTON, DC’S Street Sense Cultural Tourism DC GREATER SHAW / U STREET Justice & Sustainability September 2004 DUKE DRAFT DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK FOR A CULTURAL DESTINATION DISTRICT WITHIN WASHINGTON, DC’S GREATER SHAW / U STREET 2 “Music is my mistress, and she plays second fiddle to no one.” Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington Washington, DC’s Native Son & World Legend (1899 - 1974) DUKE DRAFT DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK FOR A CULTURAL DESTINATION DISTRICT WITHIN WASHINGTON, DC’S GREATER SHAW / U STREET 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Overview 4 II. Existing Neighborhood Context 5 III. Historic / Cultural Context 6 IV. Planning Process (Development Goals) 8 V. Market Analysis Summary 9 VI. Public Sites Overview 9 VII. Public Policy & Placemaking 10 VIII. Planning & Implementation Principles 12 A. Placemaking 13 Howard Theatre Sub-District 14 Howard Theatre (Ellington Plaza) 15 NCRC + WMATA Parcels 18 WMATA + Howard CVS 20 9th Street Sub-District 22 Housing Finance Agency Site 23 Rhode Island Avenue Sub-District 24 NCRC + United House of Prayer Parcels 25 Watha T. Daniel/Shaw Neighborhood Library Site 26 African American Civil War Memorial Sub-District 28 Grimke School 29 Howard Town Center Area Sub-District 30 Lincoln Common Sub-District 31 B. Design Guides 32 1. Comprehensive Plan - Land Use 33 2. Shaw School Urban Renewal Plan 34 3. Historic Districts 35 4. Zoning 36 5. Mixed Land Uses 38 6. Transportation & Parking 39 5. -

Budget Letter

February 28, 2019 The Honorable Muriel Bowser Mayor of the District of Columbia 1350 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20002 Re: Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Proposal Dear Mayor Bowser: As you prepare your Fiscal Year 2020 (“FY20”) proposed budget, I would like to highlight a few Ward 5 priorities and request that you consider funding them in FY20. Last year, your Fair Shot budget made critical investments essential to Ward 5 residents such as supporting $20 million in funding for a new Lamond-Riggs library; $500,000 for new Main Streets and Clean Teams along South Dakota/Riggs Road and Bladensburg; and $300,000 for the design and creation of a statue of native Washingtonian and civil rights leader, Charles Hamilton Houston. Our Ward 5 FY20 budget is about making the District equitable and inclusive for all. From investing in affordable housing to keep residents in their homes to expanding behavioral health and trauma informed services, together, our Ward 5 FY20 budget requests moves the District towards real achievable and equitable results. Further, our Ward 5 budget represents feedback gathered from residents during my Ward 5 Budget Engagement Forum, and consideration of over 300 hours of Advisory Neighborhood Commission (ANC) and civic association meetings. 1. Affordable Housing Affordable housing remains one of the highest priorities of Ward 5 residents. With your leadership and the support of the Council, we have made critical investments in the Housing Production Trust Fund, adjusted amounts for HPAP, and other important steps to ensure housing affordability. However, the Washington Post just reported that “[i]ncome inequality is rising so fast… that data can’t keep up”. -

History 3760 Extended Syllabus

History 3760 Extended Syllabus United States, 1900-1945 American Popular Culture UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Dr. Robert J. Mueller Summer Semester 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION A: General Course Information 1. Required Reading . 3 2. Course Content & Outcomes . 3-4 3. Course Organization . 4 4. Discussion Grade . 4-5 5. Quizzes . 5 6. Writing Assignments. 5-6 7. Grade Breakdown . 7 8. Office Hours . 7 9. Academic Dishonesty. 7 10. Sexual Harassment . 7-8 11. Students with Disabilities . 8 12. Lectures & Reading Assignments. 8-9 SECTION B: Advice for Writing 1. Advice for Writing Good Essays. 11-15 2. Mueller’s Pet Peeves . 16 3. Proper Footnoting . 17-18 4. Plagiarism . 19 SECTION C: Lecture Outlines and Word Lists . 21-34 SECTION D: Helpful Information 1. How to Read or Watch a Document and Use It Effectively . 36 2. Pop Culture Sources . 37 1 History 3760 Extended Syllabus Section A General Course Information 2 UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY History 3760 -- United States, 1900-1945 (American Popular Culture) Summer Semester 2016 Wednesdays 5:15-7:45PM (IVC) INSTRUCTOR: Dr. Bob Mueller OFFICE: USU Tooele Regional Campus, Office #180 OFFICE PHONE & VOICE MAIL: (435) 797 9909 OFFICE FAX #: (435) 882-7916 OFFICE HOURS: Wednesdays, 3:00-5:00PM & by appt. E-MAIL: [email protected] WRITING TEACHING ASSISTANT: Maren Petersen E-MAIL: maren.petersen#usu.edu CELL PHONE: (435) 1. REQUIRED READING: George Moss, The Rise of Modern America (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1995) [ISBN 0-13-181587-3] Frank King, Walt and Skeezix: Book One (Drawn & Quarterly, 2005) [ISBN 1896597645] Robert J.