Species Credit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bat Echolocation Research a Handbook for Planning and Conducting Acoustic Studies Second Edition

Bat Echolocation Research A handbook for planning and conducting acoustic studies Second Edition Erin E. Fraser, Alexander Silvis, R. Mark Brigham, and Zenon J. Czenze EDITORS Bat Echolocation Research A handbook for planning and conducting acoustic studies Second Edition Editors Erin E. Fraser, Alexander Silvis, R. Mark Brigham, and Zenon J. Czenze Citation Fraser et al., eds. 2020. Bat Echolocation Research: A handbook for planning and conducting acoustic studies. Second Edition. Bat Conservation International. Austin, Texas, USA. Tucson, Arizona 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License ii Table of Contents Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................................................... vi Table of Tables ........................................................................................................................................................................ vii Contributing Authors .......................................................................................................................................................... viii Dedication…… .......................................................................................................................................................................... xi Foreword…….. .......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to Questions on Notice Environment Portfolio

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to questions on notice Environment portfolio Question No: 3 Hearing: Additional Estimates Outcome: Outcome 1 Programme: Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) Topic: Threatened Species Commissioner Hansard Page: N/A Question Date: 24 February 2016 Question Type: Written Senator Waters asked: The department has noted that more than $131 million has been committed to projects in support of threatened species – identifying 273 Green Army Projects, 88 20 Million Trees projects, 92 Landcare Grants (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3be28db4-0b66-4aef-9991- 2a2f83d4ab22/files/tsc-report-dec2015.pdf) 1. Can the department provide an itemised list of these projects, including title, location, description and amount funded? Answer: Please refer to below table for itemised lists of projects addressing threatened species outcomes, including title, location, description and amount funded. INFORMATION ON PROJECTS WITH THREATENED SPECIES OUTCOMES The following projects were identified by the funding applicant as having threatened species outcomes and were assessed against the criteria for the respective programme round. Funding is for a broad range of activities, not only threatened species conservation activities. Figures provided for the Green Army are approximate and are calculated on the 2015-16 indexed figure of $176,732. Some of the funding is provided in partnership with State & Territory Governments. Additional projects may be approved under the Natinoal Environmental Science programme and the Nest to Ocean turtle Protection Programme up to the value of the programme allocation These project lists reflect projects and funding originally approved. Not all projects will proceed to completion. -

Terrestrial Vertebrate Fauna Survey for Anketell Point Rail Alignment and Port Projects

Terrestrial Vertebrate Fauna Survey for Anketell Point Rail Alignment and Port Projects Prepared for Australian Premium Iron Management Pty Ltd FINAL REPORT 26 July 2010 Terrestrial Vertebrate Fauna Survey for Anketell Point Rail Alignment and Port Projects Australian Premium Iron Management Pty Ltd Terrestrial Vertebrate Fauna Survey for Anketell Point Rail Alignment and Port Projects Final Report Prepared for Australian Premium Iron Management Pty Ltd by Phoenix Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd Authors: Greg Harewood, Karen Crews Reviewer: Melanie White, Stewart Ford Date: 26 July 2010 Submitted to: Michelle Carey © Phoenix Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd 2010. The use of this report is solely for the Client for the purpose in which it was prepared. Phoenix Environmental Sciences accepts no responsibility for use beyond this purpose. All rights are reserved and no part of this publication may be reproduced or copied in any form without the written permission of Phoenix Environmental Sciences or Australian Premium Iron Management. Phoenix Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd 1/511 Wanneroo Road BALCATTA WA 6914 P: 08 9345 1608 F: 08 6313 0680 E: [email protected] Project code: 925-AP-API-FAU Phoenix Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd ii Terrestrial Vertebrate Fauna Survey for Anketell Point Rail Alignment and Port Projects Australian Premium Iron Management Pty Ltd TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..........................................................................................................................v 1.0 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... -

Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests?

Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? An Analysis of the State of the Nation’s Regional Forest Agreements Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? An Analysis of the State of the Nation’s Regional Forest Agreements The Wilderness Society. 2020, Creating Jobs, Protecting Forests? The State of the Nation’s RFAs, The Wilderness Society, Melbourne, Australia Table of contents 4 Executive summary Printed on 100% recycled post-consumer waste paper 5 Key findings 6 Recommendations Copyright The Wilderness Society Ltd 7 List of abbreviations All material presented in this publication is protected by copyright. 8 Introduction First published September 2020. 9 1. Background and legal status 12 2. Success of the RFAs in achieving key outcomes Contact: [email protected] | 1800 030 641 | www.wilderness.org.au 12 2.1 Comprehensive, Adequate, Representative Reserve system 13 2.1.1 Design of the CAR Reserve System Cover image: Yarra Ranges, Victoria | mitchgreenphotos.com 14 2.1.2 Implementation of the CAR Reserve System 15 2.1.3 Management of the CAR Reserve System 16 2.2 Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management 16 2.2.1 Maintaining biodiversity 20 2.2.2 Contributing factors to biodiversity decline 21 2.3 Security for industry 22 2.3.1 Volume of logs harvested 25 2.3.2 Employment 25 2.3.3 Growth in the plantation sector of Australia’s wood products industry 27 2.3.4 Factors contributing to industry decline 28 2.4 Regard to relevant research and projects 28 2.5 Reviews 32 3. Ability of the RFAs to meet intended outcomes into the future 32 3.1 Climate change 32 3.1.1 The role of forests in climate change mitigation 32 3.1.2 Climate change impacts on conservation and native forestry 33 3.2 Biodiversity loss/resource decline 33 3.2.1 Altered fire regimes 34 3.2.2 Disease 35 3.2.3 Pest species 35 3.3 Competing forest uses and values 35 3.3.1 Water 35 3.3.2 Carbon credits 36 3.4 Changing industries, markets and societies 36 3.5 International and national agreements 37 3.6 Legal concerns 37 3.7 Findings 38 4. -

Flora Fauna Assessment Lowres Part2

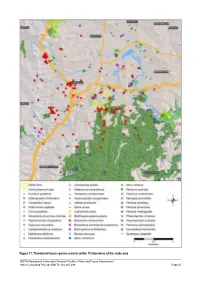

Figure 11: Threatened fauna species records within 10 kilometres of the study area SIMTA Moorebank Intermodal Terminal Facility—Flora and Fauna Assessment Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd-ABN 76 104 485 289 Page 65 3.3.2 Field Survey 3.3.2.1 Terrestrial Fauna Habitats Five broad terrestrial fauna habitat types were identified from the study area; remnant vegetation, riparian habitats, landscaped areas and cleared and disturbed areas (Figure 12). Flora and Fauna Assessment Page 66 Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd-ABN 76 104 485 289 Figure 12: Fauna habitat in the study area SIMTA Moorebank Intermodal Terminal Facility—Flora and Fauna Assessment Hyder Consulting Pty Ltd-ABN 76 104 485 289 Page 67 Remnant Vegetation Remnant Woodland Plate 27. Remnant woodland of rail corridor Plate 28. Remnant woodland of rail corridor Remnant woodland communities occur across the proposed rail corridor south of the SIMTA site (Plate 27, Plate 28). The low canopy is dominated by eucalypts and melaleucas, providing potential nesting, roosting and sheltering habitat for birds such as Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike (Coracina novaehollandiae) and Spotted Pardalote (Pardalotus punctatus). The dense shrub layer offers sheltering and foraging habitat for birds such as Red-browed Finch (Neochmia temporalis). Well-developed leaf litter and groundlayer vegetation offers sheltering and foraging habitat for reptiles such as Red-bellied Black Snake (Pseudechis porphyriacus) and Eastern brown Snake (Pseudonaja textilis). Micro-chiropteran bat species including Gould’s Wattled Bat (Chalinolobus gouldii) and the threatened Eastern Bent-wing Bat (Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis) were recorded by Anabats placed in remnant woodland, suggesting these species may forage for invertebrates above, within and along the margins of woodland vegetation. -

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter, Number 31, Nov 2008

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter, Number 31, Nov 2008 The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter Number 39 November 2012 ABS Website: http://abs.ausbats.org.au ABS Discussion list - email: [email protected] ISSN 1448-5877 © Copyright The Australasian Bat Society, Inc. (2012) The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter, Number 31, Nov 2008 The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter, Number 39, November 2012 – Instructions for Contributors – The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter will accept contributions under one of the following two sections: Research Papers, and all other articles or notes. There are two deadlines each year: 10th March for the April issue, and 10th October for the November issue. The Editor reserves the right to hold over contributions for subsequent issues of the Newsletter, and meeting the deadline is not a guarantee of immediate publication. Opinions expressed in contributions to the Newsletter are the responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australasian Bat Society, its Executive or members. For consistency, the following guidelines should be followed: Emailed electronic copy of manuscripts or articles, sent as an attachment, is the preferred method of submission. Faxed and hard copy manuscripts will be accepted but reluctantly! Please send all submissions to the Newsletter Editor at the email or postal address below. Electronic copy should be in 11 point Arial font, left and right justified with 16 mm left and right margins. Please use Microsoft Word; any version is acceptable. Manuscripts should be submitted in clear, concise English and free from typographical and spelling errors. Please leave two spaces after each sentence. -

Summer Indiana Bat Ecology in the Southern Appalachians

SUMMER INDIANA BAT ECOLOGY IN THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS: AN INVESTIGATION OF THERMOREGULATION STRATEGIES AND LANDSCAPE SCALE ROOST SELECTION _______________________ A thesis Presented to The College of Graduate and Professional Studies Department of Biology Indiana State University Terre Haute, Indiana ______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master’s in Biology _______________________ by Kristina Hammond August 2013 Kristina Hammond 2013 Keywords: Myotis sodalis, Indiana bat, thermoregulation, MaxENT, landscape, roosting ecology ii COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Joy O’Keefe, PhD Assistant Professor of Biology Indiana State University Committee Member: George Bakken, PhD Professor of Biology Indiana State University Committee Member: Stephen Aldrich, PhD Assistant Professor of Geography Indiana State University Committee Member: Susan Loeb, PhD Research Ecologist USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station & Clemson University iii ABSTRACT In the southern Appalachians there are few data on the roost ecology of the federally endangered Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis). During 2008-2012, we investigated roosting ecology of the Indiana bat in ~280,000 ha in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Cherokee National Forest, and Nantahala National Forest in the southern Appalachians Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina. We investigated 2 aspects of the Indiana bat’s roosting ecology: thermoregulation and the extrinsic factors that influence body temperature, and landscape-scale roost selection. To investigate thermoregulation of bats at roost, we used data gathered in 2012 from 6 female Indiana bats (5 adults and 1 juvenile) to examine how reproductive condition, group size, roost characteristics, air temperature, and barometric pressure related to body temperature of roosting bats. We found that air temperature was the primary factor correlated with bats’ body temperatures while at roost (P < 0.01), with few differences detected among reproductive classes in terms of thermoregulatory strategies. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Bciissue22018.Pdf

BAT CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL ISSUE 2 • 2018 // BATCON.ORG CHIROPTERAN Research and development seeks to unlock and harness the secrets of bats’ techextraordinary capabilities THE CAVERN SPECIES SPOTLIGHT: THE SWEETEST OF YOUTH TRI-COLORED BAT FRUITS BECOME a MONTHLY SUSTAINING MEMBER Photo: Vivian Jones Vivian Photo: Grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) When you choose to provide an automatic monthly donation, you allow BCI to plan our conservation programs with confidence, knowing the resources you and other sustaining members provide are there when we need them most. Being a Sustaining Member is also convenient for you, as your monthly gift is automatically transferred from your debit or credit card. It’s safe and secure, and you can change or cancel your allocation at any time. As an additional benefit, you won’t receive membership renewal requests, which helps us reduce our paper and postage costs. BCI Sustaining Members receive our Bats magazine, updates on our bat conservation efforts and an opportunity to visit Bracken Cave with up to five guests every year. Your consistent support throughout the year helps strengthen our organizational impact. TO BECOME A SUSTAINING MEMBER TODAY, VISIT BATCON.ORG/SUSTAINING OR SELECT SUSTAINING MEMBER ON THE DONATION ENVELOPE ENCLOSED WITH YOUR DESIRED MONTHLY GIFT AMOUNT. 02 }bats Issue 23 2017 20172018 ISSUE 2 • 2018 bats INSIDE THIS ISSUE FEATURES 08 CHIROPTERAN TECH For sky, sea and land, bats are inspiring waves of new technology THE CAVERN OF YOUTH 12 Bats could help unlock -

Chiropterology Division BC Arizona Trial Event 1 1. DESCRIPTION: Participants Will Be Assessed on Their Knowledge of Bats, With

Chiropterology Division BC Arizona Trial Event 1. DESCRIPTION: Participants will be assessed on their knowledge of bats, with an emphasis on North American Bats, South American Microbats, and African MegaBats. A TEAM OF UP TO: 2 APPROXIMATE TIME: 50 minutes 2. EVENT PARAMETERS: a. Each team may bring one 2” or smaller three-ring binder, as measured by the interior diameter of the rings, containing information in any form and from any source. Sheet protectors, lamination, tabs and labels are permitted in the binder. b. If the event features a rotation through a series of stations where the participants interact with samples, specimens or displays; no material may be removed from the binder throughout the event. c. In addition to the binder, each team may bring one unmodified and unannotated copy of either the National Bat List or an Official State Bat list which does not have to be secured in the binder. 3. THE COMPETITION: a. The competition may be run as timed stations and/or as timed slides/PowerPoint presentation. b. Specimens/Pictures will be lettered or numbered at each station. The event may include preserved specimens, skeletal material, and slides or pictures of specimens. c. Each team will be given an answer sheet on which they will record answers to each question. d. No more than 50% of the competition will require giving common or scientific names. e. Participants should be able to do a basic identification to the level indicated on the Official List. States may have a modified or regional list. See your state website. -

České Vernakulární Jmenosloví Netopýrů. I. Návrh Úplného Jmenosloví

Vespertilio 13–14: 263–308, 2010 ISSN 1213-6123 České vernakulární jmenosloví netopýrů. I. Návrh úplného jmenosloví Petr Benda zoologické oddělení PM, Národní museum, Václavské nám. 68, CZ–115 79 Praha 1, Česko; katedra zoologie, PřF University Karlovy, Viničná 7, CZ–128 44 Praha 2, Česko; [email protected] Czech vernacular nomenclature of bats. I. Proposal of complete nomenclature. The first and also the last complete Czech vernacular nomenclature of bats was proposed by Presl (1834), who created names for three suborders (families), 31 genera and 110 species of bats (along with names for all other then known mammals). However, his nomenclature is almost forgotten and is not in common use any more. Although more or less representative Czech nomenclatures of bats were later proposed several times, they were never complete. The most comprehensive nomenclature was proposed by Anděra (1999), who gave names for all supra-generic taxa (mostly homonymial) and for 284 species within the order Chiroptera (ca. 31% of species names compiled by Koopman 1993). A new proposal of a complete Czech nomenclature of bats is given in the Appendix. The review of bat taxonomy by Simmons (2005) was adopted and complemented by several new taxa proposed in the last years (altogether ca. 1200 names). For all taxa, a Czech name (in binomial structure for species following the scientific zoological nomenclature) was adopted from previous vernacular nomenclatures or created as a new name, with an idea to give distinct original Czech generic names to representatives of all families, in cases of species- -rich families also of subfamilies or tribes. -

The Evolution of Echolocation in Bats: a Comparative Approach

The evolution of echolocation in bats: a comparative approach Alanna Collen A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment, University College London. November 2012 Declaration Declaration I, Alanna Collen (née Maltby), confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, this is indicated in the thesis, and below: Chapter 1 This chapter is published in the Handbook of Mammalian Vocalisations (Maltby, Jones, & Jones) as a first authored book chapter with Gareth Jones and Kate Jones. Gareth Jones provided the research for the genetics section, and both Kate Jones and Gareth Jones providing comments and edits. Chapter 2 The raw echolocation call recordings in EchoBank were largely made and contributed by members of the ‘Echolocation Call Consortium’ (see full list in Chapter 2). The R code for the diversity maps was provided by Kamran Safi. Custom adjustments were made to the computer program SonoBat by developer Joe Szewczak, Humboldt State University, in order to select echolocation calls for measurement. Chapter 3 The supertree construction process was carried out using Perl scripts developed and provided by Olaf Bininda-Emonds, University of Oldenburg, and the supertree was run and dated by Olaf Bininda-Emonds. The source trees for the Pteropodidae were collected by Imperial College London MSc student Christina Ravinet. Chapter 4 Rob Freckleton, University of Sheffield, and Luke Harmon, University of Idaho, helped with R code implementation. 2 Declaration Chapter 5 Luke Harmon, University of Idaho, helped with R code implementation. Chapter 6 Joseph W.