Americanensemble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual

PB 1854 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual 1 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual Contributing Authors Alan B. Galloway Area Farm Management Specialist [email protected] Megan Bruch Leffew Marketing Specialist [email protected] Dr. David Mercker Extension Forestry Specialist [email protected] Foreword The authors are indebted to the author of the original Production of Christmas Trees in Tennessee (Bulletin 641, 1984) manual by Dr. Eyvind Thor. His efforts in promoting and educating growers about Christmas tree production in Tennessee led to the success of many farms and helped the industry expand. This publication builds on the base of information from the original manual. The authors appreciate the encouragement, input and guidance from the members of the Tennessee Christmas Tree Growers Association with a special thank you to Joe Steiner who provided his farm schedule as a guide for Chapter 6. The development and printing of this manual were made possible in part by a USDA specialty crop block grant administered through the Tennessee Department of Agriculture. The authors thank the peer review team of Dr. Margarita Velandia, Dr. Wayne Clatterbuck and Kevin Ferguson for their keen eyes and great suggestions. While this manual is directed more toward new or potential choose-and-cut growers, it should provide useful information for growers of all experience levels and farm sizes. Parts of the information presented will become outdated. It is recommended that prospective growers seek additional information from their local University of Tennessee Extension office and from other Christmas tree growers. 2 Tennessee Christmas Tree Production Manual Contents Chapter 1: Beginning the Planning ............................................................................................... -

Oh Christmas Tree(S), Oh Christmas Tree(S) Raising Trees a Family Affair for Locals

Merry Christmas! THURSDAY, DECEMBER 24, 2015 COVERING ALTON, BARNSTEAD, & NEW DURHAM - WWW.NEWHAMPSHIRELAKESANDMOUNTAINS.COM FREE Oh Christmas tree(s), oh Christmas tree(s) Raising trees a family affair for locals BY CATHY ALLYN end from Thanksgiving Contributing Writer until Christmas. REGION — Ask a kid Sarah indicated the what he wants to grow “amazing” thing about on his family’s farmland the Christmas indus- and instead of spinach try is “getting to see the and broccoli, he’s apt to same faces” year after say, “Christmas trees.” year. That’s what Tony “At first, I’d say I was Grasso did when his married to Tony and parents bought 51 acres the customers would in Laconia back in the go, ‘You mean the little early 1980s. No doubt in- guy?’ because they still fluenced by a friend who thought of him as the son also grew trees, his par- who worked there,” she ents went along with his said. “Now we’re getting suggestion and P and T to show off our girls to Tree Company was born. those same customers.” Now an Alton resi- Many of those people dent, Grasso shares re- have been regulars for sponsibilities with his 30 years. “It’s interesting parents as well as own for them to see our fam- family: wife Sarah, and ily grow and we get to daughters Sydney and see theirs grow,” Sarah Amelia. observed. “I started working Six-year-old Sydney there the Thanksgiving enjoys going to work be- COURTESY PHOTO before Tony proposed to cause she considers it A FAMILY business calls for all members to help, no matter how young. -

Farmers Market Promotion Program (FMPP) Final Performance Report

Farmers Market Promotion Program (FMPP) Final Performance Report The final performance report summarizes the outcome of your FMPP award objectives. As stated in the FMPP Terms and Conditions, you will not be eligible for future FMPP or Local Food Promotion Program grant funding unless all close-out procedures are completed, including satisfactory submission of this final performance report. This final report will be made available to the public once it is approved by FMPP staff. Write the report in a way that promotes your project's accomplishments, as this document will serve as not only a learning tool, but a promotional tool to support local and regional food programs. Particularly, recipients are expected to provide both qualitative and quantitative results to convey the activities and accomplishments of the work. The report is limited to 10 pages and is due within 90 days of the project’s performance period end date, or sooner if the project is complete. Provide answers to each question, or answer “not applicable” where necessary. It is recommended that you email or fax your completed performance report to FMPP staff to avoid delays: FMPP Phone: 202-690-4152; Email: [email protected]; Fax: 202-690-4152 Should you need to mail your documents via hard copy, contact FMPP staff to obtain mailing instructions. Report Date Range: September 30, 2014- September 29, 2016 (e.g. September 30, 20XX-September 29, 20XX) Authorized Representative Name: Bonnie Riedesel Authorized Representative Phone: 540-885-5174 Authorized Representative Email: [email protected] Recipient Organization Name: Central Shenandoah Planning District Commission Project Title as Stated on Grant Agreement: Shenandoah Valley Fields of Gold Agritourism Program Grant Agreement Number: 14-FMPPX-VA-0096 (e.g. -

Christmas Tree Farms | Supporting Nonprofits | Shopping Local

2020 GUIDE CHRISTMAS TREE FARMS | SUPPORTING NONPROFITS | SHOPPING LOCAL 2020 | HOLIDAY GUIDE 1 from all of us at Johnson-Witkemper Local and family owned, Johnson-Witkemper Insurance wants to invite you to call us for the best in service and competitive insurance programs. Whether it be for Auto, Home, Business, Life or Health Insurance, we promise to do our best for you. 33rd Anniversary 49th Anniversary at Johnson-Witkemper, Inc. at Marvin Johnson & Associates, Inc. 305 Washington Street, Columbus, Indiana IN-35058556 (812) 372-7829 www.jwinsurance.com 12 Months No GE® 30” GE® 30” Free Standing Slide In Electric Interest/Same As Electric Range Convection Range Cash. Comes in various Comes in various All Financing is colors/ nishes colors/ nishes #JB735 #JS760 Subject to Credit Visit Website Visit website Approval. for details for details COUPON FREE 10 year component warranty on purchase Earn up to $2000* Receive up to a of $499 or more With purchase of select, customizable Cafe appliance suites. $2000 rebate ($80 value) with the purchase of select Cafe appliance Now Thru 12/31 suite combinations. 1647 National Rd, Columbus, IN 812-372-5899 42 Public Square, Shelbyville, IN 317-398-6236 www.bishoppsappliance.com SHELBYVILLE HOURS: 8 am-6 pm Mon-Fri; Sat. 8 am-4 pm; Closed Sundays www.bishoppsappliance.com 1647 National Rd 42 Public Square Columbus, IN Shelbyville, IN We o er free & quick in store and 812-372-5899 317-398-6236 curb side pick up or delivery. IN-35058534 2020 | HOLIDAY GUIDE 3 table of contents 5 Christmas tree farms 12 Supporting nonprofits 16 Shopping locally 22 Give adventure 24 Winter squash recipes Let us know what you would like to see in next year’s issue. -

Download Choose & Cut

YOUR GUIDE TO NORTH CAROLINA CHOOSE & CUT FARMS CHRISTMAS 2020 www.NCchristmastrees.com “Where the Perfect North Carolina Fraser Fir Christmas Trees are Grown” OVER 45,000 TREES TO CHOOSE FROM 3-17 FT. Unique Christmas Shoppe Overnight Hotel-Motel 828-765-0019 Packages Available Celebrating Our Visit with Santa • Free Refreshments 50th Anniversary! Free Covered Wagon Hay Rides e-mail: [email protected] • see a map to our farm at www.sugarplumfarm.com OPENING FOR SEASON FUN THE WEEKEND BEFORE THANKSGIVING FRIDAY 3PM-5:30PM • SATURDAY 9AM-5:30PM SUNDAY 12-5:30PM Fraser Fir Christmas Trees • Custom Wreaths Personalized Decorative Items & Gifts OPEN 9AM-DUSK ON BLACK FRIDAY DIRECTIONS: From NC Hwy 221-N, take a left at the first red light (163/194 intersection); then, take the first left at next light onto Beaver Creek School Rd. Travel approx. 2.5 miles and Frosty’s will be on the right. 2152 Beaver Creek School Rd • West Jefferson, NC 28694 www.GoFrostys.com • 800-238-TREE COUNTY MAP CHOOSE&CUT & DIRECTORY Alleghany Johnson, TN Ashe Carter, TN Watauga Mitchell Avery North Yancey Randolph Carolina Piedmont Madison Area Burke Buncombe Haywood Lincoln Jackson Cherokee Western North Carolina ALLEGHANY GLADE VALLEY, LAUREL SPRINGS CHEROKEE TOPTON WATAUGA BLOWING ROCK, BOONE, VILAS Lil’ Grandfather Choose & Cut Tree Farm..... 5 Fir Heaven Sake Christmas Tree Farm .......22 Appalachian Evergreens .............................36 Wishon Evergreens/McInnis Tree Farm ........ 7 C&J Christmas Trees ................................36 HAYWOOD CANTON, WAYNESVILLE Circle C Tree Farms ................................... 37 ASHE FLEETWOOD, LAUREL SPRINGS, Boyd Mountain Christmas Tree Farm .........23 WEST JEFFERSON Dutch Cove Christmas Tree Farm ............. -

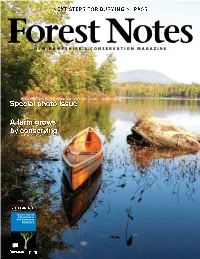

Special Photo Issue a Farm Grows by Conserving

NEXT STEPS FOR BURYING N. PASS Forest Notes NEW HAMPSHIRE’S CONSERVATION MAGAZINE Special photo issue A farm grows by conserving AUTUMN 2015 forestsociety.org Locate Your Organization Here Convenient access to the water & Portsmouth Harbor The Historic Creek Farm e ForestFFororest SSocietyociettyy is lookinglooking forfor a partnerpartner with similar sstewardshiptewarddshipship interinterestseestssts to lease the buildings and 35-a35-acrecre ccoastaloastal prpropertyoperty at CrCreekeek FFarmarm in PPortsmouth.ortsmouth. AvailableAvailable in 2017 – SuitableSuittabable forfor nonprotnnonprot organizationsorgganizanizations or institinstitutionsutionsu – HHistHistoric,isttororic, 19,460 sqsq.. ft. cottcottagetagaggee with 2-st2-storytorororyy utilitutilitytyy buildingbuildiing and garageggararragage – 1,125 ffeeteet off frfrontageonttagaggee on SSagamoreaggamoramorree CrCreekreekeeeek – DoDockck and aaccessccesscess ttoo PPorPortsmouthortsmouth HHarbHarborarbor Historic, 19,460 sq. ft. cottage with 2-story utility building and garage Contact Jane James 115050 MirMironaona Rd PPortsmouth,ortsmouth, NH 03801 CelCell:ll:l: (603) 817-0649 [email protected]@marpleleejames.comjames.com TABLE OF CONTENTS: AUTUMN 2015, N o. 284 4 23 30 DEPARTMENTS 2 THE FORESTER’S PRISM 3 THE WOODPILE 14 IN THE FIELD Fall is tree-tagging season at The Rocks Estate. FEATURE 16 CONSERVATION SUCCESS STORIES 4 Winning Shots How a conservation easement is protecting working forests while A photo essay featuring the winners of the First Annual providing capital that will help the last dairy farm in Temple, N.H. Forest Notes Photo Contest. keep growing. A landowner in Wilton with roots going back to the town’s first settlers donates a conservation easement on his hilltop farm. 23 WOODS WISE Most of our reservations aren’t well-known recreation destinations, and that can be a good thing. -

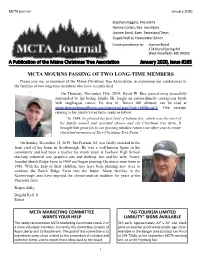

January 2020 Newsletter

MCTA Journal January 2020 Stephen Higgins, President Norma Corliss, Rec. Secretary Joanne Bond, Exec. Secretary/Treas. Dugald Kell Jr, Newsletter Editor Correspondence to: Joanne Bond 174 Bond Spring Rd West Newfield, ME 04095 A Publication of the Maine Christmas Tree Association January 2020, Issue #265 MCTA MOURNS PASSING OF TWO LONG-TIME MEMBERS Please join me, as members of the Maine Christmas Tree Association, in expressing our condolences to the families of two long-time members who have recently died. On Thursday, November 14th, 2019, David W. Rice passed away peacefully surrounded by his loving family. He fought an extraordinarily courageous battle with esophageal cancer. He was 61. Dave's full obituary can be read at www.stetsonsfuneralhome.com/memorial.aspx?oid=1680&vid=1. One passage, relating to his family's tree farm, reads as follow: “In 1989, he planted his first field of balsam firs, which was the start of his family owned and operated choose and cut Christmas tree farm. It brought him great joy to see growing families return year after year to create cherished memories at Rice Christmas Tree Farm.” On Sunday, December 15, 2019, Jim Pearson, 82, was fatally attacked in the front yard of his home in Scarborough. He was a well-known figure in his community and had been a teacher for many years at Gorham High School teaching industrial arts, graphics arts and drafting. Jim and his wife, Nancy, founded Beech Ridge Farm in 1969 and began planting Christmas trees there in 1986. With the help of their children, they have been planting new trees to continue the Beech Ridge Farm into the future. -

Choose & Cut Farm Guide 2011

CHOOSE & CUT FARM GUIDE 2011 Oregon listings Free Guide on pages 2-22 to Christmas Tree Farms Washington listings on pages 23-42 Maps on Pages 1 & 23 Pacific Northwest Christmas Tree Association P.O. Box 3366 • Salem, Oregon 97302 • (503) 364-2942 • Fax (503) 581-6819 • www.nwtrees.com FARM LOCATOR MAPS OREGON Locations noted are 20 general, please refer to specific instructions under each listing. 19 52 62 64 63 55 604469 50 53 58 66 56 45 61 51 10 42 Corbett DALL E S 43 TH E 54 67 7 5 15 11 57 68 4 12 17 9 Yamhill 59 72 65 18 13 16 14 6 70 36 8 73 71 37 221 38 41 47 46 48 33 49 39 28 31 30 34 40 32 35 26 223 29 27 Ki n g s Va ll e y 2 3 1 •Le b a n o n 21 22 Veneta 24 23 25 RO S E BU rg 1 CHOOSE & CUT GROWERS OF OREGON BENTON 1 DONOVAN’S CHRISTMAS TREES (541) 758-6237 5720 S.W. Donovan Place Nov. 20 – Dec. 24 Corvallis, OR 97333 Weekdays: 10 am – 6 pm [email protected] Weekends: 9 am – 6 pm www.donovanplace.com Location: West Corvallis. 1/2 mile south of Benton County fairgrounds. Turn off 53rd Ave. onto Willow. Follow Willow 3 blocks, turn right on 56th. Go one block, turn left onto Donovan Place. Species Available: Noble, Douglas-fir, Grand, Nordmann, Scotch pine, Concolor, Blue spruce, Norwegian spruce. Services: Saws, Restrooms, Wreaths, Coffee/Beverages, Cutting assistance, Gift shop, Fresh cut trees, Hay/wagon/trailer rides. -

Santa at Illinois Christmas Tree Farms 5/24/20, 2�58 PM

Santa at Illinois Christmas Tree Farms 5/24/20, 258 PM (/) About Us (/index.php/25-santa-in-chicago-about-us-3) Contact Santa (/index.php/contact-santa) Find Santa in Chicago (/index.php) Hire A Santa (/index.php/hire-a-santa) Santa for Your Event (/index.php/santa-for-your-event) Santa Photographers (/index.php/santa-photographers) Free Gifts from Santa (/index.php/free-gifts-from-santa) Contact Santa (/index.php/contact-santa) Santa Videos (/index.php/santa-videos) Santa Events Santa at Illinois Christmas Tree Farms More Santa Events Top 10 Santa Events Unusual Santa Events (/index.php? (/index.php/20-offbeat- layout=edit&id=20) unusual-fascinating-chicago- area-santa-events) Free Santa Events (/index.php/8-free-santa- Story Time with Santa christmas-events-in- (/index.php/21-stories-with- chicagoland-northern-illinois) santa-and-mrs-claus) Santa at Tree Farms Santa at Area Malls (/index.php/18-santa-at- (/index.php/14-santa-at-chicagoland- illinois-christmas-tree-farms) malls-department-stores) Special Needs Children Events in Cities and Towns (/index.php/28-santa-events- Home Visits from Santa in-cities-and-towns-in- St. Nicholas Events chicagoland-and-northern- illinois) Santa Houses Santa Pictures Holiday A great adventure for children is to go with Mom and Dad to an Happenings Santa Pet Pictures Illinois Christmas tree farm and pick their own tree, plus have a Top 10 Christmas Events Santa from Past Times visit with Santa Claus at the same time. Most of the Illinois Christmas tree farms listed here are an easy drive from the Top 25 Christmas Party Ideas Santa on the Train Chicago area, although a couple are further out so you may Top 20 Places for Holiday want to consider making it an overnight excursion. -

Oklahoma Growers Want Their Trees to Be a Part of Your Holiday Season

Oklahoma growers want their trees to be a part of your holiday season. By Mike Nichols 8 • Oklahoma Country • Fall 2008 While you may not have started your Christmas shopping and other Sequoyah County Farm Bureau member Matt Jarvis serves as vice preparations, a small group of Oklahomans has been busy since last president of the OCTA, and this Christmas season will be the second he year’s Yuletide with its efforts directed toward December 25, 2008. and his family will have trees ready for harvest. The 27 member-growers of the Oklahoma Christmas Tree “OCTA is working hard to promote Oklahoma-grown Christmas Association (OCTA) hope a tree from one of their “choose and cut” trees,” said Matt, whose operation is located near Muldrow about 5 1/2 farms will be the centerpiece of your holiday decorations. miles north of Interstate 40 on state Highway 64-B. Those producers should have more than 6,500 fresh, Oklahoma- “We’re all so spread out that we’re not really competitors. We help each grown trees available for this year’s Christmas season. other by sharing information and learning from each others’ mistakes.” Julie and Matt, who reside north of Muldrow, are members of Sequoyah County Farm Bureau. The Christmas tree growers can be reached by telephone at 918-427-5913. Oklahoma Country • Fall 2008 • 9 Matt’s tree plot occupies only a small portion of his 10 acres, but County countryside about five years ago after living in urban Fort Smith contains hundreds of pines and cypresses in perfectly straight rows for about seven years. -

Treemendous News Is Emailed to Our Contact Me and I Inquire with the Dept

TTRREEEEmmeennddoouuss NNeewwss Florida Christmas Tree Association’s Newsletter July 2015 FALL MEETING AT MILTON, FLORIDA Presidents Comments: or have a friend or relative pull it up on any computer. Mike & Erica Kelly and Joyce Schnoor are setting up an exciting Fall Meeting on We made an error by not setting the date of August 22nd. They are always busy, so we our fall meeting well in advance. Craig may have to help trim some trees when we Sorensen would have come had we done get there. The whole program is set up on so. Please speak up if you would like to the farm with speakers, lunch, and drinks. host the Fall Meeting 2016, and would It will be nice to see everyone again. everyone please advise us when you would like the meeting to be held. Craig Sorensen, Tim Mitchell Supplies and We have interested people phone all year Tree Stands, (800-394-6536 or 615-497- for information about the FCTA and where 2299) (See Advertisement) will be unable they can get seedlings. I answer specific to attend due to the Texas Meeting. Phone questions, but I always refer them to the in your orders ASAP. Those that live near web site: www.flchristmastrees.com where Jodi Utsman can pick up your prepaid they can gather information and see the orders at Jodi’s farm. Those who live near Seedling Report for information on where Jacksonville, can have Michael Songer pick seedlings are available. Whenever you up netting and smaller items at the find someone interested in the FCTA, Franklin, TN Tim Mitchell warehouse. -

Growing Christmas Trees in the Pacific Northwest

Growing PNW 6 • Revised June 2003 hristmas CTrees in the Pacific Northwest A Pacific Northwest Extension Publication C. Landgren, R. Fletcher, M. Bondi, Oregon State University • University of Idaho D. Barney, and R. Mahoney Washington State University Contents History and trends ........................................ 2 Popular species in the region ..................... 21 Colorado blue spruce ............................... 22 Judging opportunity and risk ...................... 3 Concolor fir ............................................. 23 Motivation ................................................. 3 Douglas-fir ............................................... 24 Time commitment...................................... 3 Fraser fir .................................................. 25 Evaluating your site ................................... 3 Grand fir .................................................. 26 Marketing options and decisions ............... 4 Noble fir................................................... 27 Risks .......................................................... 4 Nordmann fir ........................................... 28 Christmas tree management cycle .............. 5 Scots pine................................................. 29 Christmas tree growing tasks..................... 5 Shasta fir .................................................. 30 Farm planning ....................................... 5 Turkish fir ................................................ 31 Site preparation ....................................