2021 Police Reform & Reinvention Collaborative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of New Haven

UUniversityniversity ooff NEW HAVEN 22008008 WOOMENMEN’S SOOCCERCCER BAALANCELANCE • PAASSIONSSION • SPPORTSMANSHIPORTSMANSHIP • LEEARNINGARNING • SEERVICERVICE • REESOURCEFULNESSSOURCEFULNESS University of New Haven Visit www.newhaven.edu or call 1-800-DIAL-UNH (342-5864), Ext. 7319 QUICK FACTS RESIDENTIAL LIFE Founded: 1920 Making you feel at home is a priority at UNH. Our on-campus Campus: Located in West Haven, Conn., 80 acres on a housing is available in 10 residence halls. A five-story, 400-bed hilltop overlooking Long Island Sound and the culturally rich city of apartment-style residence hall, with beautiful views of Long Island New Haven. A southeastern branch is located in New London, Sound, is set to open in fall of 2009. Residential Life staff members Conn. live in each hall and help promote an atmosphere conducive to Enrollment: 3000 undergraduate 5000 total enrollment study and social interaction among students. Residence Hall Student Ratio: 50% Male, 50% Female Councils, composed of students elected by their peers, plan social Geographic Distribution: 40 states and 53 countries and recreational activities and serve as representatives for students Diversity: 18% from minority groups (all categories) living in each hall. Room accommodations range from traditional residence halls (equipped with a fitness room and campus conven- FACULTY ience store) to multi-bedroom, apartment-style residences. Over 80% hold PhD’s or the highest degree in their fields. Many have backgrounds as working professionals and are consultants to Connecticut businesses, bringing hands-on experience to the The David A. classroom. UNH has a student-to-faculty ratio of 14:1. Beckerman Recreation Center, shown here ACADEMIC PROGRAMS opened in the UNH offers Associate’s, Bachelor’s, and Master’s Degrees in 4 Fall of 2007. -

Academic All-America All-Time List

Academic All-America All-Time List Year Sport Name Team Position Abilene Christian University 1963 Football Jack Griggs ‐‐‐ LB 1970 Football Jim Lindsey 1 QB 1973 Football Don Harrison 2 OT Football Greg Stirman 2 OE 1974 Football Don Harrison 2 OT Football Gregg Stirman 1 E 1975 Football Don Harrison 2 T Football Greg Stirman 2 E 1976 Football Bill Curbo 1 T 1977 Football Bill Curbo 1 T 1978 Football Kelly Kent 2 RB 1982 Football Grant Feasel 2 C 1984 Football Dan Remsberg 2 T Football Paul Wells 2 DL 1985 Football Paul Wells 2 DL 1986 Women's At‐Large Camille Coates HM Track & Field Women's Basketball Claudia Schleyer 1 F 1987 Football Bill Clayton 1 DL 1988 Football Bill Clayton 1 DL 1989 Football Bill Clayton 1 DL Football Sean Grady 2 WR Women's At‐Large Grady Bruce 3 Golf Women's At‐Large Donna Sykes 3 Tennis Women's Basketball Sheryl Johnson 1 G 1990 Football Sean Grady 1 WR Men's At‐Large Wendell Edwards 2 Track & Field 1991 Men's At‐Large Larry Bryan 1 Golf Men's At‐Large Wendell Edwards 1 Track & Field Women's At‐Large Candi Evans 3 Track & Field 1992 Women's At‐Large Candi Evans 1 Track & Field Women's Volleyball Cathe Crow 2 ‐‐‐ 1993 Baseball Bryan Frazier 3 UT Men's At‐Large Brian Amos 2 Track & Field Men's At‐Large Robby Scott 2 Tennis 1994 Men's At‐Large Robby Scott 1 Tennis Women's At‐Large Kim Bartee 1 Track & Field Women's At‐Large Keri Whitehead 3 Tennis 1995 Men's At‐Large John Cole 1 Tennis Men's At‐Large Darin Newhouse 3 Golf Men's At‐Large Robby Scott # 1 Tennis Women's At‐Large Kim Neece 1 Track & Field 1996 Women's -

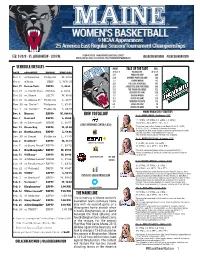

SCHEDULE/RESULTS HOW to FOLLOW the Maine Line

tyson mchatten - MAINE woMEN’S BASKETBALL CONTACT feb. 9 2020 - vs. binghamton - 1:00 p.m. OFFICE: (207) 581-3596 | CELL: (207) 992-7746 | [email protected] @Blackbearswbb #BlackBearNation SCHEDULE/RESULTS Maine TALE OF THE TAPE BING. DATE OPPONENT WATCH TIME/RES. 10-14, 6-4 record/conf. 16-6, 5-4 59.7 points per game 68.4 Nov. 8 at Delaware FloSports W, 69-56 62.8 opponent points per game 58.9 Nov. 11 at Brown NESN L, 70-76 OT -3.1 scoring margin +9.5 39.7 field goal percentage 40.5 Nov. 17 Boston Univ. ESPN+ L, 42-69 32.1 3-point field goal percentage 34.9 73.3 free throw percentage 76.5 Nov. 19 at #14 NC State ACCNX L, 34-62 30.3 rebounds per game 39.0 Nov. 24 vs. Navy# AE.TV W, 46-41 -7.2 REBOUND MARGIN +1.7 13.2 ASSISTS PER GAME 13.0 Nov. 29 vs. Arizona St.^ FloSports L, 31-57 13.5 TURNOVERS PER GAME 13.5 Nov. 30 vs. Drake^ FloSports L, 62-94 6.8 Steals PER GAME 7.0 1.2 Blocks PER GAME 3.4 Dec. 1 vs. Dayton^ FloSports L, 49-78 MAINE PROJECTED STARTERS Dec. 4 Husson ESPN+ W, 104-43 HOW TO FOLLOW 3 - G - ANNE SIMON - Freshman - 5’8” Dec. 7 Harvard ESPN+ L, 40-69 11.7 PPG, 4.5 RPG, 1.9 APG, 1.6 SPG | Dec. 10 at Dartmouth NESN L, 41-57 47.0 FG%, 30.0 3PT%, 74.5 FT% Cross insurance center (5,800) *Four-time America East Rookie of the Week (12/16/19, 1/6/20, Dec. -

Academic All-America All-Time List

Academic All-America All-Time List Year Sport Name Team Position Abilene Christian University 1963 Football Jack Griggs ‐‐‐ LB 1970 Football Jim Lindsey 1 QB 1973 Football Don Harrison 2 OT Football Greg Stirman 2 OE 1974 Football Don Harrison 2 OT Football Gregg Stirman 1 E 1975 Baseball Bill Whitaker ‐‐‐ ‐‐‐ Football Don Harrison 2 T Football Greg Stirman 2 E 1976 Football Bill Curbo 1 T 1977 Football Bill Curbo 1 T 1978 Football Kelly Kent 2 RB 1982 Football Grant Feasel 2 C 1984 Football Dan Remsberg 2 T Football Paul Wells 2 DL 1985 Football Paul Wells 2 DL 1986 Women's At‐Large Camille Coates HM Track & Field Women's Basketball Claudia Schleyer 1 F 1987 Football Bill Clayton 1 DL 1988 Football Bill Clayton 1 DL 1989 Football Bill Clayton 1 DL Football Sean Grady 2 WR Women's At‐Large Grady Bruce 3 Golf Women's At‐Large Donna Sykes 3 Tennis Women's Basketball Sheryl Johnson 1 G 1990 Football Sean Grady 1 WR Men's At‐Large Wendell Edwards 2 Track & Field 1991 Men's At‐Large Larry Bryan 1 Golf Men's At‐Large Wendell Edwards 1 Track & Field Women's At‐Large Candi Evans 3 Track & Field 1992 Women's At‐Large Candi Evans 1 Track & Field Women's Volleyball Cathe Crow 2 ‐‐‐ 1993 Baseball Bryan Frazier 3 UT Men's At‐Large Brian Amos 2 Track & Field Men's At‐Large Robby Scott 2 Tennis 1994 Men's At‐Large Robby Scott 1 Tennis Women's At‐Large Kim Bartee 1 Track & Field Women's At‐Large Keri Whitehead 3 Tennis 1995 Men's At‐Large John Cole 1 Tennis Men's At‐Large Darin Newhouse 3 Golf Men's At‐Large Robby Scott #1Tennis Women's At‐Large Kim -

Elmira College Information

Inside Elmira College Table of Contents Elmira College THE SCOOP ON Cover 1 ELMIRA COLLEGE Inside Elmira College 2 Information Sports Information 3 Location: Elmira College is a four-year, private, co 2011-12 Season Outlook 4 One Park Place -educational, liberal arts college with an undergraduate enrollment of 1,200. The Coaching Staff 5 Elmira, New York 14901 College is located in the Finger Lakes 2011-12 Player Profiles 6 (607) 735-1800 Region of Upstate New York. The average Founded: class size is 16, with a student to faculty 2011-12 Team Photo 13 ratio of 12:1. 1855 The College offers over thirty-five aca- 2011-12 Team Roster 14 Enrollment: demic majors, including: education, busi- 2010-11 Season in Review 15 ness, psychology, biology, nursing, pre- 1,200 medicine, pre-law, along with numerous 2010-11 Statistics 16 Colors: study abroad and internship programs. 2010-11 Inside the Numbers 17 Purple and Gold The Soaring Eagles sponsors ten varsity Nickname: women‘s teams in soccer, field hockey, Elmira in the ECAC West 18 volleyball, tennis, golf, basketball, cheer- Soaring Eagles leading, ice hockey, lacrosse and softball. EC Records 1973-2010 19 Affiliation: Men‘s varsity teams compete in soccer, golf, basketball, ice hockey, tennis and 100-Point Club 20 NCAA (Div. III), ECAC, lacrosse. Award Winners and Captains 21 Empire 8 Complementing the varsity sport offer- ings, are ten opportunities to participate EC Team Records 22 President: in junior varsity sports. Dr. Thomas K. Meier EC Single Game Leaders 23 Vice President of Athletics -

The Valueof an Education

SUNY Broome Alumni Magazine • Fall 2014 The Value of an Education Emil Calice leaves an extraordinary gift BCC Foundation Annual Report Inside From the Director of BROOME fall 2014 Editor: Natalie M. Thompson Alumni Affairs Designer: Ciara Cable Staff Writer: Jennifer Micale, PhD This has been one of the most exciting On the Cover: Mementos from the life of Emil Calice, including a picture of his parents for whom he honored editions of BROOME magazine that I have by name in his bequest to the College. ever worked on! We had to expand our In this issue: pages once again to cover all the significant happenings on our ever-changing campus. 1 President’s Message 2 BCC Foundation Annual Report After being temporarily relocated, I am back in my old office in the newly 3 Financial Overview renovated Darwin R. Wales Center – a beautiful gateway to the College that 4 Donor Roll you will read more about in our next issue. My move was nothing compared 6 Cover Story: The Value of an Education to that of our residents of SUNY Broome’s new on-campus Student Village. 7 Through the Lens: The Ed Aswad Collection I had the privilege of being on-hand for Move-In day – so exciting to see the 18 New Beginnings: Student Village young people and their families getting a look at their new apartments for 22 Class Notes the first time. Definitely not their parents’ “dorms”! 24 SUNY Broome News Even though it has been four months since the news broke, the campus is Contributors: Photo Credits: still energized by Emil Calice’s amazing philanthropic legacy to the College of Sue Carpenter Silvia Briga $10 million. -

Fan Culture in the American Hockey League

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Sport Management Undergraduate Sport Management Department Spring 2014 Fan Culture in the American Hockey League Julie Mros St. John Fisher College Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/sport_undergrad Part of the Sports Management Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Mros, Julie, "Fan Culture in the American Hockey League" (2014). Sport Management Undergraduate. Paper 17. Please note that the Recommended Citation provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/sport_undergrad/17 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fan Culture in the American Hockey League Abstract Knowing the fan culture of the American Hockey League will help understand what fans look for when choosing a favorite team. This information can be used to increase fan bases around the league. In order to conduct this research a survey was sent out to fans and non-fans of AHL teams. With the results collected it was found that fans favorite aspects of their favorite team’s culture is their team’s in game promotions. This data shows that in game promotions need to be a priority for American Hockey League teams, if they wish to build a better relationship with their fans as well as gain more fans. -

Men's Basketball

MEN’S BASKETBALL Varsity / Sub-Varsity Letter Recipients Conference Results Head Coaches and Yearly Team Record All-Conference Selections Assistant Coaches Other Individual Honors Captains Professional Basketball Game Scores Individual Records Year-by-Year Scoring Leaders Freshman / JV Coaches Year-by-Year Rebounding Leaders and Yearly Team Record Year-by-Year Leaders in Assists Freshman /JV Game Scores Although the first formal men’s basketball team represented the University in the 1904-05 season, some 103 years ago, the 2006-07 season was the 87TH year of the sport at Maine. The reason: the program was discontinued twice, once between 1910 and 1920, an absence of 10 seasons, and again between 1929 and 1935, an absence of six additional seasons. Reasons for the interruptions varied, ranging from finances to a lack of local opponents (Maine was the only college in the state to have a team in the mid- 1920s), to facility problems. The program was “re-born” for good in 1935, although only a single game was played in the ’35-‘36 season. It is worth noting that Bill Kenyon, a veteran coach of other UM teams, volunteered to coach the team without compensation in order to get the program reinstated. He continued to do so for six more years even though his salary did not reflect his additional duties! It is also interesting to note that while a varsity basketball program was absent for 16 seasons, the University sponsored a freshman team during those years, primarily due to the availability of local opponents in the form of high schools and prep schools where basketball was gaining a strong degree of interest. -

SUNY Binghamton Student Handbook: Harassment 06-07

Contents BINGHAMTON UNIVERSITY Discovery/Center for Academic PRESIDENT’S WELCOME LETTER ............ 1 Excellence Tutorial Services .............. 21 Writing Center ...................................... 22 BECOMING A MORE INCLUSIVE UNIVERSITY COMMUNITY ........................ 2 Financial Aid and Employment ............. 22 Campus Climate ..................................... 3 Office of the University Registrar ......... 22 Individual and Group Responsibility ....... 3 International Programs ........................ 23 Academic Freedom ................................. 3 Global Studies Integrated Curriculum (GSIC) ............................ 23 Realizing Our Goals ................................ 4 Languages Across the Curriculum ....... 23 University Diversity Advisory Council ..... 4 McNair Scholars Program .................... 24 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................ 5-7 University Libraries .............................. 24 Computing Services ............................. 25 IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS ................................................. 8 Office of the University Ombudsman .... 25 Emergencies On Campus ....................... 8 Office of Affirmative Action .................. 26 Emergencies Off Campus ....................... 8 Athletics ............................................... 26 STUDENT AFFAIRS OFFICES HELP DIRECTORY ................................ 8-13 .................. 27 Building Abbreviations ........................... 8 Office of the Vice President for Student Affairs ................................. -

Women's Lacrosse Records Book

Women’s Lacrosse Records Book 20 20 21 22 Table of Contents All-time Ivy Champions ...............................................................................1 Year-by-Year Results ................................................................................2-4 Ivy Tournament Results/Records.........................................................5-9 NCAA Championship ..........................................................................10-11 All-Ivy Teams/Notes ............................................................................12-19 All-Americans .........................................................................................20-22 Tewaaraton Trophy Winners .................................................................. 23 Academic All-Americans .......................................................................... 23 Statistical Records ................................................................................24-25 The Ivy League Women’s Lacrosse Record Book was last updated in May of 2021. Please forward edits and/or additions to [email protected]. *Note that throughout the Ivy League record books there are references to Barnard College. Prior to 1983 and the establishment of the Columbia/Barnard Athletic Consortium Barnard students competed as the “Barnard Bears.” From 1983 through the present, female teams are refered to as “Columbia Lions.” 21 1 22 Ivy League Record Book WOMEN’S LACROSSE All-Time Champions IVY CHAMPIONS Total Outright First Last Champs Champs Champ Champ Brown 0 — — — Columbia -

Library Chief Outlines How Sweet It Is Building Proposal

BETHLEHE~ PUBLICLIBRARY \)Uh G v ~QO DO_ NOT CfRCULA.Ti ' . : ' '• ·• . ' ,_,.:. ·~'-.-' ' -~ : '. -~ . Pooch park on agenda Landslide update Salute to graduates ·- 0 Page 28 _ O_hae23 __ ,.., ·'"'"'" . ttO.£-tsOtt 1.N l!YH'IXQ XAY Xli11M1t'l3a tSt All11l!SI'l JI'ISOd H3H3'IH~3S dOS MOt OO-t0-60 £tO£ H~IJ•••••••••••••••••;~••••• Volume XLIV Number 24 .. Library chief outlines How sweet it is ~· building proposal By SUSAN GRAVES which the library did, she added. r Shortly after that, the board appointed Bethlehem Public Library is second a Citizens Advisory Committee for input to none in the Capital District, and its on renovation and expansion plans. stewards want to keep it that way. "We appointed a cross section of the Although the library is still referred community, we wanted divergent to by some as "the new library," it is opinions, and we asked them to look at showing signs of age and growing pains. plans that Stewart (architect Stewart Since 1973, when the library was built, Roberts) came up with," Pieri said. circulation has doubled, and the "Ultimately, we said the original plan was children's area is over- to support a second story." ] crowded and cluttered. Another major area of That's why ·library concern is that the library is Director Nancy Pieri, the not in compliance with the ,. library board of trustees, led Americans With Disabilities by Susan Birkhead, and a Act, Pieri said. citizens advisory_ committee Expanding the library will have come up with a plan to likely be costly, but Pieri said expand the existing facility. -

2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report

COUNTY OF BROOME, NEW YORK COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 County of Broome, New York Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Year Ended December 31, 2020 Jerome Z. Knebel Director Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Gino M. Bucciarelli, Deputy Director of OMB Krista L. Soltis, Treasury Manager Tracy L. Ryan, Senior Financial Analyst County of Broome Comprehensive Annual Financial Report For the Year Ended December 31, 2020 Table of Contents I. Introductory Section Page Letter of Transmittal ................................................................................................................ 3-13 County of Broome Government Organizational Chart ............................................................... 14 County of Broome Officials ....................................................................................................... 15 County of Broome Chairs of Legislative Committees................................................................ 16 County of Broome Department Heads ....................................................................................... 17 County of Broome Office of Management and Budget (OMB) ................................................. 18 II. Financial Section Independent Auditors’ Report ............................................................................................... 23-25 Management’s Discussion and Analysis (Unaudited) .......................................................... 27-46 Basic Financial Statements: