School of Psychology and Speech Pathology a Causal Layered Analysis of Movement, Paralysis and Liminality in the Contested Arena

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOMELAND STORY Saving Country

ROGUE PRODUCTIONS & DONYDJI HOMELAND presents HOMELAND STORY Saving Country PRESS KIT Running Time: 86 mins ROGUE PRODUCTIONS PTY LTD - Contact David Rapsey - [email protected] Ph: +61 3 9386 2508 Mob: +61 423 487 628 Glenda Hambly - [email protected] Ph: +61 3 93867 2508 Mob: +61 457 078 513461 RONIN FILMS - Sales enquiries PO box 680, Mitchell ACT 2911, Australia Ph: 02 6248 0851 Fax: 02 6249 1640 [email protected] Rogue Productions Pty Ltd 104 Melville Rd, West Brunswick Victoria 3055 Ph: +61 3 9386 2508 Mob: +61 423 487 628 TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopses .............................................................................................. 3 Donydji Homeland History ................................................................. 4-6 About the Production ......................................................................... 7-8 Director’s Statement ............................................................................. 9 Comments: Damien Guyula, Yolngu Producer… ................................ 10 Comments: Robert McGuirk, Rotary Club. ..................................... 11-12 Comments: Dr Neville White, Anthropologist ................................. 13-14 Principal Cast ................................................................................. 15-18 Homeland Story Crew ......................................................................... 19 About the Filmmakers ..................................................................... 20-22 2 SYNOPSES ONE LINE SYNOPSIS An intimate portrait, fifty -

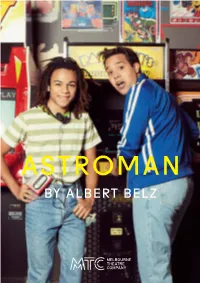

ASTROMAN by ALBERT BELZ Welcome

ASTROMAN BY ALBERT BELZ Welcome Over the course of this year our productions have taken you to London, New York, Norway, Malaysia and rural Western Australia. In Astroman we take you much closer to home – to suburban Geelong where it’s 1984. ASTROMAN In this touching and humorous love letter to the 80s, playwright Albert Belz wraps us in the highs and lows of growing up, the exhilaration of learning, and what it means to be truly courageous. BY ALBERT BELZ Directed by Sarah Goodes and Associate Director Tony Briggs, and performed by a cast of wonderful actors, some of them new to MTC, Astroman hits the bullseye of multigenerational appeal. If ever there was a show to introduce family and friends to theatre, and the joy of local stories on stage – this is it. At MTC we present the very best new works like Astroman alongside classics and international hits, from home and abroad, every year. As our audiences continue to grow – this year we reached a record number of subscribers – tickets are in high demand and many of our performances sell out. Subscriptions for our 2019 Season are now on sale and offer the best way to secure your seats and ensure you never miss out on that must-see show. To see what’s on stage next year and book your package visit mtc.com.au/2019. Thanks for joining us at the theatre. Enjoy Astroman. Brett Sheehy ao Virginia Lovett Artistic Director & CEO Executive Director & Co-CEO Melbourne Theatre Company acknowledges the Yalukit Willam Peoples of the Boon Wurrung, the First Peoples of Country on which Southbank Theatre and MTC HQ stand, and we pay our respects to all of Melbourne’s First Peoples, to their ancestors and Elders, and to our shared future. -

M Ed Ia R Elea Se M Ed Ia R Elea Se

Filmmakers announced for Cook 2020: Our Right of Reply Tuesday 14 May 2019: Screen Australia and the New Zealand Film Commission (NZFC) are pleased to announce the eight Indigenous teams from Australia and New Zealand who will work on a joint anthology feature, Cook 2020: Our Right of Reply, entitled Ngā Pouwhenua in New Zealand. The teams will each create a short chapter for the feature film, which will provide an Indigenous perspective on the 250th anniversary of James Cook’s maiden voyage to the Pacific. Mitchell Stanley (Servant or Slave) from Australia, and Bailey Mackey (All or Nothing; New Zealand All Blacks, associate producer on Hunt for the Wilderpeople) and Mia Henry-Teirney (Baby Mama’s Club) from New Zealand have been chosen as co-producers and will collaborate with the teams to develop their concepts and the overarching narrative. The teams and producers are attending a residential lab at Shark Island Institute in Kangaroo Valley to develop the film. Screen Australia’s Head of Indigenous Penny Smallacombe said: “This is a rare opportunity for creative collaboration between Indigenous cultures, from Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific. I’m inspired by the experience and talent of the filmmakers selected to helm this project. These teams have presented exceptional concepts, with stories exploring the past, present and future, with humour and horror, sadness and joy, in response to who we are and how we continue to survive the colonial experience.” MEDIA RELEASE “I’m excited by their unique storytelling styles and individual voices, and how they will complement each other to create a powerful anthology. -

Missionaries, Mercenaries, Misfits…

Missionaries, Mercenaries, Misfits… COMEDY 6 x 30’ HD COMEDY HD 6 x 30’ At the ass-end of the world, in the middle of nowhere, is Alice Springs. It’s a sacred place for Aboriginal people and a magnet for three kinds of whitefellas: Missionaries, Mercenaries and Misfits. It’s also the home of 8MMM Aboriginal Radio, where the mob meets the 3Ms. 8MMM is the proud voice of blackfellas in this part of the world. Trouble is, like most Indigenous organisations, it’s run by whitefellas. For the Missionaries, Mercenaries and Misfits of Alice Springs, ‘saving’ Aboriginal people from themselves is hard work. For Aboriginal people, being ‘saved’ all the time is exhausting. As the motley crew at 8MMM broadcasts the day-to-day goings on of Alice Springs, they find ignorance and interference at every turn - and that’s before they’ve left the building. 8MMM ABORIGINAL RADIO is truthful and bold - a comedy about tolerance, self-determination and cultural misunderstanding and why, when all else fails - which it usually does - it’s good to laugh. Australia’s first Indigenous narrative comedy, 8MMM ABORIGINAL RADIO is an original series from Alice Springs-based production company Brindle Films (Big Name No Blanket, Blown Away and producer of Double Trouble) and Princess Pictures (Summer Heights High, Angry Boys, John Safran’s Race Relations, It’s a Date). The series is written and directed by Indigenous talent, shot on location in Central Australia and features an exciting ensemble cast and local performers. WRITERS: Trisha Morton-Thomas, Danielle MacLean, Sonja Dare DIRECTORS: Dena Curtis, Adrian Russell Wills PRODUCERS: Rachel Clements, Trisha Morton-Thomas, Anna Cadden EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS: Andrea Denholm, Laura Waters PRODUCTION COMPANIES: Brindle Films, Princess Pictures. -

Shari Sebbens Looks at 'The Horrible Side' of the Country in Australia Day Garry Maddox 2 June 2017

Shari Sebbens looks at 'the horrible side' of the country in Australia Day Garry Maddox 2 june 2017 Shari Sebbens is no fan of Australia Day. A Bardi Jabirr Jabirr woman who grew up in Darwin, the Sapphires star thinks of it as Invasion Day and prefers to take time to reflect with her "mob" – family and friends – rather than celebrate. So Sebbens was surprised to hear she had been invited to audition for a new film called Australia Day. Shari Sebbens: "Why would I want to audition for a film called Australia Day?" Photo: Nic Walker "I laughed," she says. "I said 'why would I want to audition for a film called Australia Day?' As an Aboriginal woman, it conjures up that it's going to be some bogan Cronulla riots type thing." But when she read the script, Sebbens was delighted to see the provocative territory the drama was covering – a potent examination of race and identity. "It's taking a look at the horrible side to Australia that people don't like to acknowledge exists, especially on nice summer days when you can just pop on the Hottest 100 and enjoy a tinnie," she says. Sebbens plays an Aboriginal police officer, Senior Constable Sonya Mackenzie, who is caught up in interwoven dramas as three teenagers run away on the national day: a 14- 2 year-old Indigenous girl fleeing a car crash, a 17-year-old Iranian boy running from a crime scene and a 19-year-old Chinese girl escaping sexual slavery. Directed by Kriv Stenders with a cast that includes Bryan Brown, Matthew Le Nevez, Isabelle Cornish and such newcomers as Miah Madden, Elias Anton and Jenny Wu, the topical drama has its world premiere at Sydney Film Festival this month. -

Clickview ATOM Guides 1 Videos with ATOM Study Guides Title Exchange Video Link 88

ClickView ATOM Guides Videos with ATOM Study Guides Title Exchange Video Link 88 http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/8341/88 http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/21821/the-100- 100+ Club club 1606 and 1770 - A Tale Of Two Discoveries https://clickviewcurator.com/exchange/programs/5240960 http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/8527/8mmm- 8MMM Aboriginal Radio aboriginal-radio-episode-1 http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/21963/900- 900 Neighbours neighbours http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/series/11149/a-case-for- A Case for the Coroner the-coroner?sort=atoz http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/12998/a-fighting- A Fighting Chance chance https://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/33771/a-good- A Good Man man http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/13993/a-law- A Law Unto Himself unto-himself http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/33808/a-sense-of- A Sense Of Place place http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/3226024/a-sense- A Sense Of Self of-self A Thousand Encores - The Ballets http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/32209/a- Russes In Australia thousand-encores-the-ballets-russes-in-australia https://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/25815/accentuat Accentuate The Positive e-the-positive Acid Ocean http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/13983/acid-ocean http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/series/8583/addicted-to- Addicted To Money money/videos/53988/who-killed-the-economy- http://online.clickview.com.au/exchange/videos/201031/afghanist -

Community Development Committee - Agenda

Community Development Committee - Agenda Community Development Committee Business Paper for July 2020 Monday, 13 July 2020 Via Teleconference Councillor Jimmy Cocking (Chair) 1 Community Development Committee - Agenda ALICE SPRINGS TOWN COUNCIL COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE AGENDA FOR THE MEETING TO BE HELD ON MONDAY 13 JULY 2020 VIA TELECONFERENCE 1. APOLOGIES 2. RESPONSE TO PUBLIC QUESTIONS 3. DISCLOSURE OF INTEREST 4. MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING 4.1. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Community Development Committee – 15 June 2020 4.2. Business Arising 5. IDENTIFICATION OF ITEMS FOR DISCUSSION 5.1. Identification of items for discussion 5.2. Identification of items to be raised in General Business by Elected Members and Officers 6. DEPUTATIONS Nil 7. PETITIONS 8. NOTICE OF MOTION 9. REPORTS OF OFFICERS 9.1. Community Development Directorate Update Report No. 151/20cd (DCS) 9.2 ASTC Art Collection – Report on Activities 2019/20 Report No. 152/20cd (MCCD) 9.3 Brindle Films Sponsorship Application Report No. 162/20cd (MCCD) 9.4 Creative Arts Recovery Package Report No. 163/20cd (MCCD) 9.5 Phoney Film Festival Prize Report No. 164/20cd (YDO) 10. REPORTS OF ADVISORY AND EXECUTIVE COMMITTEES 10.1. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Seniors Coordinating Committee – 17 June 2020 10.2. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Tourism, Events & Promotions Committee – 25 June 2020 10.3. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – ASALC Committee – 30 June 2020 10.4. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Youth Action Group Committee – 1 July 2020 Page 2 2 Community Development Committee - Agenda 10.5. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Public Art Advisory Committee – 6 July 2020 11. GENERAL BUSINESS 12. NEXT MEETING: Monday 17 August 2020 CONFIDENTIAL SECTION 13. APOLOGIES - CONFIDENTIAL 14. -

2019/20 Annual Report

Annual Report 2019/20 ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 1 RESPONSIBLE BODY’S DECLARATION In accordance with the Financial Management Act 1994, I am pleased to present Film Victoria’s Annual Report for the year ending 30 June 2020. Ian Robertson AO President Film Victoria August 2020 Contents Role and Vision 4 A Message from Film Victoria’s President 6 A Message from Film Victoria’s CEO 7 Performance 9 Year in Review 11 Strategic Priority One: 13 Position the Victorian screen industry to create high quality, diverse and engaging content Fiction Features 14 Fiction Series 16 Documentary 18 Games 20 Production Attraction and Regional Assistance 22 Developing Skills and Accelerating Career Pathways 25 Fostering and Strengthening Diversity 28 Strategic Priority Two: 31 Promote screen culture Strategic Priority Three: 35 Provide effective and efficient services Governance and Report of Operations 39 Establishment and Function 40 Governance and Organisational Structure 41 Film Victoria’s Board 42 Committees and Assessment Panels 44 Overview of Financial Performance and Position 46 During 2019/20 Employment Related Disclosures 47 Other Disclosures 50 Financial Statements 55 Disclosure Index 81 ANNUAL REPORT 2019/20 3 Role Film Victoria is the State Government agency that provides strategic leadership and assistance to the film, television and digital media sectors of Victoria. Film Victoria invests in projects, businesses and people, and promotes Victoria as a world-class production destination nationally and internationally. The agency works closely with industry and government to position Victoria as a leading centre for technology and innovation through the growth and development of the Victorian screen industry. -

Carry-The-Flag-Press-Kit-Jmbl.Pdf

Link to Trailer https://vimeo.com/215101133/ password CTF Link to website www.tamarindtreepictures.com Contact Us AUSTRALIA Tamarind Tree Pictures Danielle MacLean +61411491613 [email protected] Synopsis Short - This is a rich and powerful story of a man whose design created meaning for a people once invisible to mainland Australia, the people of the Torres Strait. Long - In 2017 it is the 25th anniversary of the Torres Strait Flag. For Bernard Namok Jnr, ‘Bala B’ the flag is a poignant reminder of home, family and the father he hardly knew. Bernard Namok Senior won the flag design competition in 1992 but a year later, at just 31 years, he died leaving behind his wife with four young children. Journey across the Torres Straits with Bala B to honour his father’s legacy. A rich and powerful story of a man whose design created meaning for a people once invisible to mainland Australia, the people of the Torres Strait. Story Bernard Namok Jnr, is a Senior Broadcaster and presenter of ‘Mornings with Bala B’ at The Top End Aboriginal Bush Broadcasting Association – TEABBA. Everyday he speaks to thousands of Indigenous Australians across the Northern Territory but he feels disconnected from his own culture and family. When he sees the Torres Strait Islands flag flying, it is for him, not only the symbol of identity of his people, but a poignant reminder of his home and the father he hardly knew. Bernard Namok Senior won the Torres Strait Islander flag design competition in 1992 but a year after his flag was formally recognised, at 31 years of age, he died leaving behind a wife and four young children. -

Module 5 Things to Do

Continuing Your Journey -Module 5 Things to do • Find out about an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander medical or legal service or other community organisation operating where you live. Learn about the history of the organisation — many organisations have their histories on their websites. See what support you can give. Offer to work voluntarily. • Read the latest report on Closing the Gap. You can also read the shadow reports published by the Australian Human Rights Commission as part of the Close the Gap campaign. Read Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership 2007, From hand out to hand up: Cape York Welfare Reform Project: Aurukun, Coen, Hope Vale, Mossman Gorge: design recommendations, Cape York Institute for Policy and Leadership, Cairns, Queensland. Indigenous Dispute Resolution & Conflict Management Case Study Project 2009, Solid work you mob are doing: case studies in Indigenous dispute resolution & conflict management in Australia, report prepared for the National Alternative Dispute Resolution Advisory Council, Canberra. Norman, H 2015, ‘What do we want?’ A political history of Aboriginal land rights in New South Wales, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra. Skyring, F 2011, Justice: a history of the Aboriginal Legal Service of WA, UWA Publishing, Perth. Wunan Foundation Inc. 2015, Empowered communities: empowered peoples: design report, Wunan Foundation Inc., Sydney. Watch 8MMM Aboriginal Radio, 2015, television program, Princess Pictures Nominees and Brindle Films, Australia. Agnes Abbott: hard worker, 2007, short documentary, CAAMA Productions, Australia. Always have and always will, 2006, short documentary, CAAMA Productions, Australia. Green bush, 2005, short film, CAAMA Productions, Australia. Jarlmadangah: our dream our reality, 2007, short documentary, CAAMA Productions, Australia. -

M Ed Ia R Elea Se

Indigenous Department announces $1.5 million in special funding Wednesday 1 August 2018: Screen Australia’s Indigenous Department has announced the 20 recipients of a range of special funding programs. Two web series have been funded through the Black Space initiative, eight short films will be developed through Short Blacks, three documentaries about the Indigenous response to climate change will go into production through State of Alarm and seven enterprises are being supported via Indigenous Screen Business. A further documentary project also received production funding and a web series received development funding outside of these programs. Successful projects include Hunter Page-Lochard (Cleverman, Spear) and Carter Simpkin’s Short Blacks film Closed Doors; Kutcha’s Carpool Koorioke created by Black Space recipient John Harvey, as well as Indigenous Screen Business funding that has been provided to production company BUNYA (Mystery Road, Sweet Country, Goldstone) to grow their current business model. The funding has been awarded as part of the Indigenous Department’s 25th anniversary celebrations. “Supporting Indigenous screen story tellers is as vital as supporting the Indigenous businesses behind them. This funding is being distributed across a diverse group of strong Indigenous production companies who will use the financial support to strengthen Indigenous business planning as well as assist slate development through the employment of key business personnel.” said Penny Smallacombe, Head of Indigenous at Screen Australia. MEDIA RELEASE “For 25 years the Indigenous Department has put our people in control of their own stories. The funding model has been incredibly successful and has even inspired other countries to do the same for their Indigenous creators. -

Community Development Committee - Agenda

Community Development Committee - Agenda Community Development Committee Business Paper for March 2020 Monday, 16 March 2020 Council Chamber, Civic Centre Councillor Jimmy Cocking (Chair) 1 Community Development Committee - Agenda ALICE SPRINGS TOWN COUNCIL COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE AGENDA FOR THE MEETING TO BE HELD ON MONDAY 16 March 2020 IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBER, CIVIC CENTRE, ALICE SPRINGS 1. APOLOGIES 2. WELCOME TO THE PUBLIC AND VISITORS AND PUBLIC QUESTION TIME 3. DISCLOSURE OF INTEREST 4. MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING 4.1. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Community Development Committee - 10 February 2020 4.2. Business Arising 5. IDENTIFICATION OF ITEMS FOR DISCUSSION 5.1. Identification of items for discussion 5.2. Identification of items to be raised in General Business by Elected Members and Officers 6. DEPUTATIONS 6.1 John Bermingham – Alice Springs Running and Walking Club 7. PETITIONS 8. NOTICE OF MOTION 9. REPORTS OF OFFICERS 9.1. Community Development Directorate Update Report No. 43/20 cd (A/DCD) 9.2 Council Tourism Budget Opportunities Report No. 44/20cd (MCCD) 10. REPORTS OF ADVISORY AND EXECUTIVE COMMITTEES 10.1. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Seniors Coordinating Committee – 19 February 2020 10.2. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Australia Day Coordinating Committee – 20 February 2020 10.3. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Tourism, Events & Promotions Committee – 27 February 2020 10.4. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Youth Action Group Committee – 4 March 2020 10.5. UNCONFIRMED Minutes – Public Art Advisory Committee – 11 March 2020 11. GENERAL BUSINESS 12. NEXT MEETING: Tuesday 14 April 2020 Page 2 2 Community Development Committee - Agenda CONFIDENTIAL SECTION 13. APOLOGIES - CONFIDENTIAL 14. DISCLOSURE OF INTEREST - CONFIDENTIAL 15. MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS MEETING – CONFIDENTIAL 15.1.